PGM-17 Thor

| SM-75/PGM-17A Thor | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Type | Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| Used by |

United States Air Force (testing) Royal Air Force (operational deployment) |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1957 |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| Produced | 1959–1960 |

| No. built | About 225; peak deployment was 60 |

| Variants |

Delta rockets Thor rocket family |

| Specifications | |

| Weight | 49,590 kilograms (109,330 lb) at launch. |

| Length | 19.76 metres (64 ft 10 in). |

| Diameter | 2.4 metres (8 ft). |

Thor was the first operational ballistic missile deployed by the U.S. Air Force (USAF). Named after the Norse god of thunder, it was deployed in the United Kingdom between 1959 and September 1963 as an intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with thermonuclear warheads. Thor was 65 feet (20 m) in height and 8 feet (2.4 m) in diameter. It was later augmented in the U.S. IRBM arsenal by the Jupiter.

A large family of space launch vehicles—the Thor and Delta rockets—were derived from the Thor design. The Delta II is still in active service as of 2017 and with the retirement of Atlas and Titan in the mid-2000s is the last surviving "heritage" launch vehicle in the US fleet, being derived from a Cold War-era missile system.

Design and development

Fearful that the Soviet Union would deploy a long-range ballistic missile before the U.S., in January 1956 the USAF began developing the Thor, a 1,500 miles (2,400 km) intermediate-range ballistic missile. The program proceeded quickly, and within three years of inception the first of 20 Royal Air Force Thor squadrons became operational in the UK. The UK deployment carried the codename 'Project Emily'. One of the advantages of the design was that, unlike the Jupiter IRBM, the Thor could be carried by the USAF's cargo aircraft of the time, which made its deployment more rapid. The launch facilities were not transportable, and had to be built on site. The Thor was a stop-gap measure, and once the first generation of ICBMs based in the US became operational, Thor missiles were quickly retired. The last of the missiles was withdrawn from operational alert in 1963.

A small number of Thors, converted to "Thrust Augmented Delta" launchers, remained operational in the anti-satellite missile role as Program 437 until April 1975. These missiles were based on Johnston Island in the Pacific Ocean and had the ability to destroy satellites in low Earth orbit. With prior warning of an impending launch, they could destroy a Soviet spy satellite soon after orbital insertion. These missiles remain in storage, and could be reactivated, although the W-49 Mod 6 warheads were all dismantled by June 1976.

Initial development

Development of the Thor was initiated by the USAF in 1954. The goal was a missile system that could deliver a nuclear warhead over a distance of 1,150 to 2,300 miles (1,850 to 3,700 km) with a CEP of 2 miles (3.2 km). This range would allow Moscow to be hit from a launch site in the UK.

The initial design studies were headed by Cmdr. Robert Truax (US Navy) and Dr. Adolph K. Thiel (Ramo-Wooldridge Corporation, formerly of Redstone Arsenal). They refined the specifications to an IRBM with:

- A 1,750 miles (2,820 km) range

- 8 ft (2.4 m) diameter, 65 ft (20 m) long (so it could be carried by Douglas C-124 Globemaster)

- A gross takeoff weight of 110,000 lb (50,000 kg)

- Propulsion provided by half of the Navaho-derived Atlas booster engine (due, largely, to the lack of any alternatives at this early date)

- 10,000 mph (4.5 km/s) maximum speed during warhead reentry

- Inertial guidance system with radio backup (for low susceptibility to enemy disruption)

Like Atlas, Thor utilized vernier engines for roll control; they flanked the main engine instead of being on the sides of the missile.

On 30 November 1955, three companies were given one week to bid on the project: Douglas, Lockheed, and North American Aviation. They were asked to create "a management team that could pull together existing technology, skills, abilities, and techniques in 'an unprecedented time.'" On 27 December 1955 Douglas was awarded the prime contract for the airframe and integration. The Rocketdyne division of North American Aviation was awarded the engine contract, AC Spark Plug the primary inertial guidance system, Bell Labs the backup radio guidance system, and General Electric the nose cone/reentry vehicle.

Douglas further refined the design by choosing bolted tank bulkheads (as opposed to the initially suggested welded ones) and a tapered fuel tank for improved aerodynamics. The engine was developed as a direct descendant of the Atlas MA-3 booster engine. Changes involved removal of one thrust chamber and a rerouting of the plumbing to allow the engine to fit within the smaller Thor thrust section. Engine tests were being performed as of March 1956. The first engineering model engine was available in June, followed by the first flight engine in September. Engine development was complicated by serious turbopump problems. Early Thor engines suffered from "bearing walking", a phenomenon that occurred at high altitude as the air thinned, causing the lubricant oil in the pump to foam and push the bearings out of their sockets. When this happened, the turbopump would shut down, terminating engine thrust. The initial Thor tests in 1957 used an early version of the Rocketdyne LR-79 engine with a conical thrust chamber and 135,000 pounds of thrust. By early 1958, this had been replaced by an improved model with a bell-shaped thrust chamber and 150,000 pounds of thrust. The fully developed Thor IRBM had 162,000 pounds of thrust.

First launches

Thor test launches were to be from LC-17 at Cape Canaveral Missile Annex. The development schedule was so compressed that plans for the Atlas bunker were used to allow the completion of the facility in time. Nevertheless, pad LC-17B was just ready for the first test flight.

The first flight-ready Thor, Missile 101, arrived at Cape Canaveral in October 1956. It was erected on LC-17B and underwent several practice propellant loading/unloading exercises, a static firing test, and a month-long delay while a defective relay was replaced. Launch finally took place on 25 January 1957. The Thor failed almost immediately at liftoff as the engine lost thrust, dropped back onto the pad, and exploded. Engineers could not determine the cause until viewing film of prelaunch preparations that showed crews dragging a LOX filler hose through a sandy area. It was concluded that debris had entered the LOX and contaminated it, causing valve failure.

Thor 102 was launched on 20 April. The booster was performing normally, but an erroneous console readout caused the Range Safety Officer to believe that it was headed inland and he initiated the destruct sequence 35 seconds into the launch. It was then found that a tracking console was wired in reverse, causing the Thor's trajectory to be shown as the opposite of where the missile was headed; the short flight raised confidence that it would fly.

The third Thor launch (Missile 103) did not get off the pad and exploded four minutes before the planned launch. A defective valve allowed LOX tank pressure to build up to unsafe levels; the accident was also the fault of technicians failing to pay attention to pressure gauges. LC-17B consequently had to be repaired for the second time in four months.

The inexperience of the Air Force's BMD and Douglas led to easily avoidable failures during the early Thor tests in comparison to the veterans of Wernher von Braun's team at ABMA who had more success with the Jupiter program and fewer careless mistakes. General Bernard Schreiver, head of the Air Force Ballistic Missile Division (BMD), blamed the failures on Thor test director Ed Hall, an unpleasant and unprofessional individual who drank heavily, micromanaged the program, and blamed others for its problems. He also openly rooted for Jupiter missiles to explode during test flights. Schreiver fired him after the Thor 103 disaster.

Missile 104, launched 22 August from the newly opened LC-17A, broke up at T+92 seconds due to a drop in signal strength from the programmer, causing the engine to gimbal hard right. The guidance system tried to compensate, but ended up producing uncontrolled yaw maneuvers that caused excessive structural loads.

Thor 105 (20 September), 21 months after the start of construction, flew 1,100 miles (1,800 km) downrange. No telemetry equipment was included on this missile and the weight savings allowed it to achieve a total range of 1,500 miles (2,400 km).

Missile 107 (3 October) fell back onto LC-17A and exploded at launch due to the gas generator valve failing to open.

Missile 108 (11 October), exploded around T+140 seconds without prior warning. Engineers were bewildered as to the cause of the failure. After the first Thor-Able launch failed six months later due to a seized turbopump, it was concluded to be the cause of 108's demise, although the missile did not have sufficient instrumentation to determine the exact nature of the failure.

The final three Thor tests during 1957 were all successful. 1958 began with back-to-back failures. Thor 114 was destroyed by Range Safety 150 seconds into launch when the guidance system lost power and Thor 120's engine shut down slightly under two minutes after liftoff. The telemetry system had experienced a power failure during launch, so the reason for the engine cutoff could not be satisfactorily determined.

On 19 April, Missile 121 dropped back onto LC-17B and exploded, putting the pad out of action for three months. A fuel duct collapse was believed to have been the culprit.

On 22 April, Missile 117, carrying the first Able upper stage, lost thrust and broke up at T+146 seconds due to a turbopump failure.

The Jupiter, Thor, and Atlas missiles all used a variant of the Rocketdyne LR-79 engine and all three suffered launch failures due to a marginal turbopump design. There were two separate problems with the pumps. The first was the discovery during testing at Huntsville that the lubricant oil tended to foam at high altitude as the air pressure decreased. The other was that pump shaft vibration from the nearly 10,000 RPM operating speed would cause the bearings to come out of their sockets, resulting in the pump abruptly seizing up. The Army had suspended Jupiter launches for four months until the turbopump issues could be resolved, and as a result no more pump failures affected that program.

General Schreiver rejected the idea of sending Thor and Atlas missiles back to the factory and decided that he would only allow in-field modifications so as to not delay the testing program. He agreed to install the fixes for the lubricant issue, which included pressurizing the turbopump gearboxes and using an oil with a different viscosity that was less prone to foaming, but not the modified bearing retainers. Six consecutive Thor and Atlas launches failed during February–April 1958, although not all of them could be attributed to turbopump problems. Then there were no turbopump failures for the next four months, leaving the Air Force with a sense of overconfidence that was rudely ended when Thor-Able 127, carrying the world's first lunar probe, exploded during launch on 17 August due to a turbopump failure. A month later, Atlas 6B also suffered a turbopump failure, and after this, the Air Force gave in and agreed to replace the turbopumps in all of their missiles, after which there were no more launch failures due to a turbopump problem. The necessary modifications to the missiles would have taken only one month and not caused any delay to either Thor-Able 1 or Atlas 6B's flights, thus those failures were ultimately attributed to poor management of the programs.

Five successful Thor tests were conducted in June–July 1958, the last one carrying a mouse named Wickie on a biological mission; the capsule sank into the ocean and could not be recovered. Thor 126 (26 July) lost thrust 50 seconds into launch when a LOX valve inadvertently closed. The vehicle pitched down and broke up from aerodynamic loads. Then on 30 July, a tragic accident occurred at the Thor static test stand in Sacramento, California when a LOX valve failed, causing a fire that severely burned six Douglas technicians, three of whom later succumbed to their injuries.

Phase II testing with the AC Spark Plug inertial guidance system began 7 December with the first successful flight on 19 December 1957.[1]

The operational variant of the Thor, the DM-18A, began testing in the autumn of 1958, but Missile 138 (5 November) went out of control shortly after liftoff and had to be destroyed. Nonetheless, Thor was declared operational and testing now began at Vandenberg Air Force Base on the West Coast when Missile 151 flew successfully on 16 December. On 30 December, a near repeat performance of the 5 November failure happened when Missile 149 lost control and was destroyed 40 seconds into launch.

After a run of successful launches during the first half of 1959, Missile 191, the first to be launched by a Royal Air Force crew, suffered another control malfunction while being launched from VAFB. This time, the missile's pitch and roll program failed to activate and it continued flying straight up. Launch crews initially did nothing as they reasoned that the Earth's rotation would gradually take it away from land and they wished to continue collecting data as long as possible. Eventually though, they became nervous about it exploding or pitching over, so the destruct command was sent around 50 seconds into launch. High-altitude wind caused debris to land in the town of Orcutt near the base. After Thor 203 repeated the same failure four weeks later, an investigation found that the culprit was a safety wire that had been meant to prevent the control tape in the programmer from inadvertently coming loose during vehicle assembly. The wire would ordinarily be cut after installation of the programmer in the missile, but Douglas technicians had forgotten this important step, thus the tape could not be spooled and the pitch and roll sequence did not activate. Another 23 Thor missile tests were carried out during 1959, with only one failure, when Missile 185 on 16 December, the second RAF launch, broke up due to a control malfunction.

Service rivalry with Jupiter

The Jupiter missile, a joint effort of Chrysler and the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, had originally been developed for submarine launching, but would have involved the extremely risky situation of a liquid-fueled rocket stored in the confines of a submarine. By 1956, the Polaris program was proposed instead, which featured a solid-fueled SLBM that was much lighter and safer to store. The Navy quickly switched to Polaris and dropped Jupiter, which was then transferred to the Army as a terrestrial missile.

With two IRBMs of nearly identical capabilities, the Army and Air Force were at loggerheads with each other as it seemed obvious that only one of the two would ultimately achieve operational status. Jupiter's testing program, which began two months after Thor's, proceeded more smoothly and avoided accidents such as the explosion of Thor 103 due in large part to the employment of the experienced rocket team of Wernher von Braun. The turbopump issues that plagued early Rocketdyne engines were also resolved in Jupiter much earlier than the Air Force's missiles.

The Jupiter program was more successful also due to far better testing and preparation, for example, each missile was given a full duration static firing in Huntsville prior to delivery. A static firing stand for Thor tests was only opened in May 1958, at which point the missile's launch record stood at four successes and nine failures, including four pad explosions. For comparison, there had been only three Jupiter failures as May 1958 ended (only eight launches had taken place against Thor's thirteen) with no pad explosions. Thors were given a PFRF (Pre Flight Readiness Firing) prior to launch; these were between 5–15 seconds only as the launching facilities were not designed for a full duration firing as a static test stand was. Missile 107 had not been given a PFRF at all and its launch ended in a pad explosion.

Thanks to the thorough testing done at Huntsville, Jupiter missiles mostly all arrived at CCAS in flight-ready condition while Thors typically required extensive repairs or modification before launch.

The panic that struck the US after the Soviet launches of Sputnik 1–2 in late 1957 caused Secretary of Defense Charles Wilson, in his final act before leaving office, to announce instead that both Thor and Jupiter would go into service. This was both out of fear of Soviet capabilities and also to avoid political repercussions from the workplace layoffs that would result at either Douglas or Chrysler if one of the two missiles were cancelled.

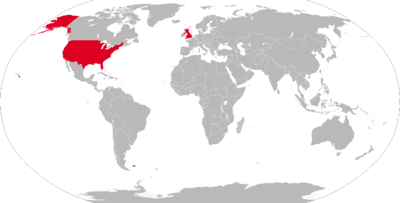

Deployment

Deployment of the IRBM fleet to Europe proved more difficult than expected, as no NATO members other than Great Britain accepted the offer to have Thor missiles stationed on their soil. Italy and Turkey both agreed to accept Jupiter missiles. Thor was deployed to the UK starting in August 1958, operated by 20 squadrons of RAF Bomber Command under US-UK dual key control.[2] The first active unit was No. 77 Squadron RAF at RAF Feltwell in 1958, with the remaining units becoming active in 1959. All were deactivated by September 1963.

All 60 of the Thor missiles deployed in the UK were based at above-ground launch sites. The missiles were stored horizontally on transporter-erector trailers and covered by a retractable missile shelter. To fire the weapon, the crew used an electric motor to roll back the missile shelter, essentially a long shed mounted on steel rails, then used a powerful hydraulic launcher-erector to lift the missile to an upright position for launch. Once it was standing on the launch mount, the missile was fueled and could be fired. The entire launch sequence, from starting to roll back the missile shelter through to ignition of the rocket engine and lift-off, took approximately 15 minutes. Main engine burn time was almost 2.5 minutes, boosting the missile to a speed of 14,400 ft/s (4,400 m/s). Ten minutes into its flight the missile reached an altitude of 280 miles (450 km), close to the apogee of its elliptical flight path. At that point the reentry vehicle separated from the missile fuselage and began its descent toward the target. Total flight time from launch to target impact was approximately 18 minutes.

The Thor was initially deployed with a very blunt conical G.E. Mk 2 'heat sink' re-entry vehicle. They were later converted to the slender G.E. Mk 3 ablative RV. Both RVs contained a W-49 thermonuclear warhead with an explosive yield of 1.44 megatons.

The IRBM program was quickly eclipsed by the Air Force's ICBM program and made redundant. By 1959, with Atlas well on its way to operational status, Thor and Jupiter became obsolete, although both remained in service as missiles until 1963. In retrospect, the IRBM program was a poorly conceived idea as it depended on the cooperation of NATO allies, most of whom were not willing to have nuclear missiles on their soil, and was also surpassed by the ICBM program, yet continued anyway for political reasons and a desire to keep the workforce at their respective assembly plants employed.

Thor's lasting legacy was not as a missile, but its use as the basis for the Thor/Delta space launcher family into the 21st century.

Noteworthy flights

- 2 June 1962, failed Bluegill flight, tracking lost after launch, Thor and nuclear device destroyed.

- 19 June 1962, failed Starfish flight, Thor and nuclear device destroyed 59 seconds after launch at 30–35,000 feet (9.1–10,668.0 m) altitude.

- 8 July 1962, Thor missile 195 launched a Mk4 reentry vehicle containing a W49 thermonuclear warhead to an altitude of 250 miles (400 km). The warhead detonated with a yield of 1.45 Mt of TNT (6.07 PJ). This was the Starfish Prime event of nuclear test series Operation Fishbowl.

- 25 July 1962, failed Bluegill Prime flight, Thor and nuclear device destroyed on launch pad, which was contaminated with plutonium.[3]

Launch vehicle

The Thor rocket was also used as a space launch vehicle. It was the first in a large family of space launch vehicles—the Delta rockets. Thor's descendants fly to this day as the Delta II and Delta IV.

Operators

Former operators

- 705th Strategic Missile Wing (1958–1960)

- RAF Bomber Command

see Project Emily Stations and Squadrons

Specifications (PGM-17A)

- Family: Thor IRBM, Thor DM-18 (single stage LV); Thor DM-19 (rocket 1st stage), Thor DM-21 (rocket 1st stage), Thor DSV-2D,E,F,G (suborbital LV), Thor DSV-2J (anti-ballistic missile), Thor DSV-2U (orbital launch vehicle).

- Overall length: 19.82 m (65.0 ft)

- Span: 2.74 m (9.0 ft)

- Weight: 49,800 kg (109,800 lb)

- Empty weight: 3,125 kg (6,889 lb)

- Thrust (vac): 760 kN

- Liftoff Thrust (sl): 670 kN (150,000 lbf)

- Isp: 282 s (2.77 kN·s/kg)

- Isp(sl): 248 s (2.43 kN·s/kg)

- Burn time: 165 s

- Core Diameter: 2.44 m

- Maximum range: 2,400 km (1,500 mi)

- Ceiling: 480 km (300 mi)

- Warhead

- One W49 warhead on Mk. 2 reentry vehicle

- warhead mass: 1,000 kg (2,200 lb)

- Yield: equivalent to 1.44 Megatons of TNT (6.02 PJ)

- CEP: 1 km (0.62 mi)

- Boost Propulsion: Liquid fuelled rocket, LOX and Kerosene.

- Engines:

- Rocketdyne LR79-NA-9 (Model S-3D); 666 kN (150000 lbf)

- Vernier: 2x Rocketdyne LR101-NA; 4.5 kN (1000 lbf) each

- Propellants: LOX/Kerosene (Thor kerosene propellant was referred to as 'RP1' by RAF users)

- Thrust (vac): 760 kN

- Isp: 282 s (2.77 kN·s/kg)

- Isp (sea level): 248 s (2.43 kN·s/kg)

- Burn time: 165 s

- Mass Engine: 643 kg

- Diameter: 2.44 m

- Chambers: 1

- Chamber Pressure: 4.1 MPa

- Area Ratio: 8.00

- Thrust to Weight Ratio: 120.32

- Country: USA

- First Flight: 1958

- Last Flight: 1980

- Flown: 145.

- Comments: Designed for booster applications. Gas generator, pump-fed

- Guidance: Inertial

- Maximum speed: 17,740 km/h (11,020 mph)

- Development Cost US dollars: $500 million

- Recurring Price US dollars: $6.25 million

- Total Number Built: 224

- Total Development Built: 64

- Total Production Built: 160

- Flyaway Unit Cost: US$750,000 in 1958 dollars

- Launches: 59

- Failures: 14

- Success Rate: 76.27%

- First Launch Date: 25 January 1957

- Last Launch Date: 5 November 1975

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to PGM-17 Thor. |

- Related lists

References

- ↑ James N. Gibson, Nuclear Weapons of the United States, An Illustrated History, pp. 167–168, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., Atglen, PA, 1996

- ↑ Sam Marsden (1 August 2013). "Locks on nuclear missiles changed after launch key blunder". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Defense Nuclear Agency. Operation Dominic I. 1962. Report DNA 6040F. Page 229-241.

Further reading

- Boyes, John. Project Emily: The Thor IRBM and the Royal Air Force 1959–1963. Prospero, Journal of the British Rocketry Oral History Programme (BROHP) No 4, Spring 2007.

- Boyes, John. Project Emily: Thor IRBM and the RAF. Tempus Publishing, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7524-4611-0.

- Boyes, John. The Thor IRBM: The Cuan Missile Crisis and the subsequent run-down of the Thor Force. pub: Royal Air Force Historical Society. Journal 42, May 2008. ISSN 1361-4231.

- Boyes, John. Thor Ballistic Missile: The United States and United Kingdom in Partnership. Fonthill Media, 2015. ISBN 978-1-78155-481-4.

- Forsyth, Kevin S. Delta: The Ultimate Thor. In Roger Launius and Dennis Jenkins (Eds.), To Reach The High Frontier: A History of U.S. Launch Vehicles. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2002. ISBN 0-8131-2245-7.

- Hartt, Julian. The Mighty Thor: Missile in Readiness. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1961.

- Melissen, Jan. "The Thor saga: Anglo‐American nuclear relations, US IRBM development and deployment in Britain, 1955–1959." Journal of Strategic Studies 15#2 (1992): 172-207.

RAF Squadrons

- Jefford, Wing Commander C.G., MBE, BA, RAF(Retd.). RAF Squadrons, a Comprehensive record of the Movement and Equipment of all RAF Squadrons and their Antecedents since 1912. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1988 (second edition 2001). ISBN 1-85310-053-6. p. 178.

- Wynn, Humphrey. RAF Strategic Nuclear Deterrent Forces, their Origins, Roles and Deployment 1946–69. London: HMSO, 1994. ISBN 0-11-772833-0. p. 449.

External links

- Thor from Encyclopedia Astronautica

- Thor IRBM History site

- History of the Delta Launch Vehicle

- UK Thor missile launch sites on Secret Bases website

- UK Thor deployment in Lincolnshire

- Maxwell Hunter, "Father of the Thor Rocket"

- "YouTube contemporary film of Thor missiles at North Pickenham"