Thomas Young (scientist)

| Thomas Young | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born |

13 June 1773 Milverton, Somerset, England |

| Died |

10 May 1829 (aged 55) London, England |

| Fields |

Physics Physiology Egyptology |

| Alma mater |

University of Edinburgh Medical School University of Göttingen Emmanuel College, Cambridge |

| Known for |

Wave theory of light Double-slit experiment Astigmatism Young–Helmholtz theory Young temperament Young's Modulus |

|

Signature | |

Thomas Young (13 June 1773 – 10 May 1829) was an English polymath and physician. Young made notable scientific contributions to the fields of vision, light, solid mechanics, energy, physiology, language, musical harmony, and Egyptology. He "made a number of original and insightful innovations"[1] in the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs (specifically the Rosetta Stone) before Jean-François Champollion eventually expanded on his work. He was mentioned by, among others, William Herschel, Hermann von Helmholtz, James Clerk Maxwell, and Albert Einstein. Young has been described as "The Last Man Who Knew Everything".[2]

Biography

Young belonged to a Quaker family of Milverton, Somerset, where he was born in 1773, the eldest of ten children. At the age of fourteen Young had learned Greek and Latin and was acquainted with French, Italian, Hebrew, German, Aramaic, Syriac, Samaritan, Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Amharic.[3]

Young began to study medicine in London at St Bartholomew's Hospital in 1792, moved to the University of Edinburgh Medical School in 1794, and a year later went to Göttingen, Lower Saxony, Germany, where he obtained the degree of doctor of medicine in 1796 from the University of Göttingen. In 1797 he entered Emmanuel College, Cambridge.[4] In the same year he inherited the estate of his granduncle, Richard Brocklesby, which made him financially independent, and in 1799 he established himself as a physician at 48 Welbeck Street, London (now recorded with a blue plaque). Young published many of his first academic articles anonymously to protect his reputation as a physician.

In 1801 Young was appointed professor of natural philosophy (mainly physics) at the Royal Institution. In two years, he delivered 91 lectures. In 1802, he was appointed foreign secretary of the Royal Society, of which he had been elected a fellow in 1794. He resigned his professorship in 1803, fearing that its duties would interfere with his medical practice. His lectures were published in 1807 in the Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and contain a number of anticipations of later theories.

In 1811 Young became physician to St George's Hospital, and in 1814 he served on a committee appointed to consider the dangers involved in the general introduction of gas into London. In 1816 he was secretary of a commission charged with ascertaining the precise length of the second's or seconds pendulum (the length of a pendulum whose period is exactly 2 seconds), and in 1818 he became secretary to the Board of Longitude and superintendent of the HM Nautical Almanac Office.

Young was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1822.[5] A few years before his death he became interested in life insurance,[6] and in 1827 he was chosen one of the eight foreign associates of the French Academy of Sciences. In 1828, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Death, legacy and reputation

Thomas Young died in London on 10 May 1829, and was buried in the cemetery of St. Giles Church in Farnborough, Kent, England. Westminster Abbey houses a white marble tablet in memory of Young bearing an epitaph by Hudson Gurney:[7][8]

Sacred to the memory of Thomas Young, M.D., Fellow and Foreign Secretary of the Royal Society Member of the National Institute of France; a man alike eminent in almost every department of human learning. Patient of unintermitted labour, endowed with the faculty of intuitive perception, who, bringing an equal mastery to the most abstruse investigations of letters and of science, first established the undulatory theory of light, and first penetrated the obscurity which had veiled for ages the hieroglyphs of Egypt. Endeared to his friends by his domestic virtues, honoured by the World for his unrivalled acquirements, he died in the hopes of the Resurrection of the just. — Born at Milverton, in Somersetshire, 13 June 1773. Died in Park Square, London, 10 May 1829, in the 56th year of his age.

Young was highly regarded by his friends and colleagues. He was said never to impose his knowledge, but if asked was able to answer even the most difficult scientific question with ease. Although very learned he had a reputation for sometimes having difficulty in communicating his knowledge. It was said by one of his contemporaries that, "His words were not those in familiar use, and the arrangement of his ideas seldom the same as those he conversed with. He was therefore worse calculated than any man I ever knew for the communication of knowledge."[9]

Later scholars and scientists have praised Young's work although they may know him only through achievements he made in their fields. His contemporary Sir John Herschel called him a "truly original genius".[10] Albert Einstein praised him in the 1931 foreword to an edition of Newton's Opticks. Other admirers include physicist Lord Rayleigh and Nobel laureate Philip Anderson.

Thomas Young's name has been adopted as the name of the London-based Thomas Young Centre, an alliance of academic research groups engaged in the theory and simulation of materials.

Research

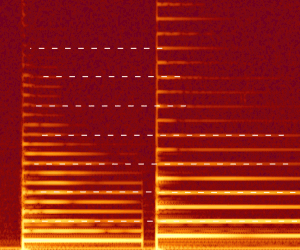

Wave theory of light

In Young's own judgment, of his many achievements the most important was to establish the wave theory of light.[11][12] To do so, he had to overcome the century-old view, expressed in the venerable Isaac Newton's Opticks, that light is a particle. Nevertheless, in the early-19th century Young put forth a number of theoretical reasons supporting the wave theory of light, and he developed two enduring demonstrations to support this viewpoint. With the ripple tank he demonstrated the idea of interference in the context of water waves. With the Young's interference experiment, or double-slit experiment, he demonstrated interference in the context of light as a wave.

"The experiments I am about to relate ... may be repeated with great ease, whenever the sun shines, and without any other apparatus than is at hand to every one", is how Thomas Young, speaking on 24 November 1803, to the Royal Society of London, began his description of the historic experiment. His talk was published in the following year's Philosophical Transactions,[13] and was destined to become a classic, still reprinted and read today.[14]

In the subsequent paper entitled Experiments and Calculations Relative to Physical Optics, published in 1804, Young describes an experiment in which he placed a narrow card (approximately 1/30th inch) in a beam of light from a single opening in a window and observed the fringes of colour in the shadow and to the sides of the card. He observed that placing another card before or after the narrow strip so as to prevent light from the beam from striking one of its edges caused the fringes to disappear.[15] This supported the contention that light is composed of waves.[16] Young performed and analysed a number of experiments, including interference of light from reflection off nearby pairs of micrometre grooves, from reflection off thin films of soap and oil, and from Newton's rings. He also performed two important diffraction experiments using fibres and long narrow strips. In his Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts (1807) he gives Grimaldi credit for first observing the fringes in the shadow of an object placed in a beam of light. Within ten years, much of Young's work was reproduced and then extended by Fresnel. (Tony Rothman in Everything's Relative and Other Fables from Science and Technology argues that there is no clear evidence that Young actually did the two-slit experiment. See also Newton wave–particle duality.)

Young's modulus

Young described the characterization of elasticity that came to be known as Young's modulus, denoted as E, in 1807, and further described it in his Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts.[17]

However, the first use of the concept of Young's modulus in experiments was by Giordano Riccati in 1782 – predating Young by 25 years.[18]

Furthermore, the idea can be traced to a paper by Leonhard Euler published in 1727, some 80 years before Thomas Young's 1807 paper.

The Young's modulus relates the stress (pressure) in a body to its associated strain (change in length as a ratio of the original length); that is, stress = E × strain, for a uniaxially loaded specimen. Young's modulus is independent of the component under investigation; that is, it is an inherent material property (the term modulus refers to an inherent material property). Young's Modulus allowed, for the first time, prediction of the strain in a component subject to a known stress (and vice versa). Prior to Young's contribution, engineers were required to apply Hooke's F = kx relationship to identify the deformation (x) of a body subject to a known load (F), where the constant (k) is a function of both the geometry and material under consideration. Finding k required physical testing for any new component, as the F = kx relationship is a function of both geometry and material. Young's Modulus depends only on the material, not its geometry, thus allowing a revolution in engineering strategies.

Young's problems in sometimes not expressing himself clearly were shown by his own definition of the modulus The modulus of the elasticity of any substance is a column of the same substance, capable of producing a pressure on its base which is to the weight causing a certain degree of compression as the length of the substance is to the diminution of its length. When this explanation was put to the Lords of the Admiralty, their clerk wrote to Young saying Though science is much respected by their Lordships and your paper is much esteemed, it is too learned ... in short it is not understood.[19]

Vision and colour theory

Young has also been called the founder of physiological optics. In 1793 he explained the mode in which the eye accommodates itself to vision at different distances as depending on change of the curvature of the crystalline lens; in 1801 he was the first to describe astigmatism;[20] and in his lectures he presented the hypothesis, afterwards developed by Hermann von Helmholtz, that colour perception depends on the presence in the retina of three kinds of nerve fibres.[21] This foreshadowed the modern understanding of colour vision, in particular the finding that the eye does indeed have three colour receptors which are sensitive to different wavelength ranges.

Young–Laplace equation

In 1804, Young developed the theory of capillary phenomena on the principle of surface tension.[22] He also observed the constancy of the angle of contact of a liquid surface with a solid, and showed how from these two principles to deduce the phenomena of capillary action.

In 1805, Pierre-Simon Laplace, the French philosopher, discovered the significance of meniscus radii with respect to capillary action.

In 1830, Carl Friedrich Gauss, the German mathematician, unified the work of these two scientists to derive the Young–Laplace equation, the formula that describes the capillary pressure difference sustained across the interface between two static fluids.

Young was the first to define the term "energy" in the modern sense.[23]

Young's equation and Young–Dupré equation

Young's equation describes the contact angle of a liquid drop on a plane solid surface as a function of the surface free energy, the interfacial free energy and the surface tension of the liquid. Young's equation was developed further some 60 years later by Dupré to account for thermodynamic effects, and this is known as the Young–Dupré equation.

Medicine

In physiology Young made an important contribution to haemodynamics in the Croonian lecture for 1808 on the "Functions of the Heart and Arteries," where he derived a formula for the wave speed of the pulse[24] and his medical writings included An Introduction to Medical Literature, including a System of Practical Nosology (1813) and A Practical and Historical Treatise on Consumptive Diseases (1815).

Young devised a rule of thumb for determining a child's drug dosage. Young's Rule states that the child dosage is equal to the adult dosage multiplied by the child's age in years, divided by the sum of 12 plus the child's age.

Languages

In an appendix to his Göttingen dissertation (1796; "De corporis hvmani viribvs conservatricibvs. Dissertatio.") there are four pages added proposing a universal phonetic alphabet (so as 'not to leave these pages blank'; lit.: "Ne vacuae starent hae paginae, libuit e praelectione ante disputationem habenda tabellam literarum vniuersalem raptim describere"). It includes 16 "pure" vowel symbols, nasal vowels, various consonants, and examples of these, drawn primarily from French and English.

In his Encyclopædia Britannica article "Languages", Young compared the grammar and vocabulary of 400 languages.[2] In a separate work in 1813, he introduced the term Indo-European languages, 165 years after the Dutch linguist and scholar Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn proposed the grouping to which this term refers in 1647.

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Young made significant contribution in the decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs. He started his Egyptology work rather late, in 1813, when the work was already in progress among other researchers.

He began by using a demotic alphabet of 29 letters built up by Johan David Åkerblad in 1802 (14 turned out to be incorrect). Åkerblad was correct in stressing the importance of the demotic text in trying to read the inscriptions, but he wrongly believed that demotic was entirely alphabetic.[25]

By 1814 Young had completely translated the "enchorial" (demotic, in modern terms) text of the Rosetta Stone (he had a list with 86 demotic words), and then studied the hieroglyphic alphabet but initially failed to recognise that the demotic and hieroglyphic texts were paraphrases and not simple translations.[26]

There was considerable rivalry between Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion while both were working on hieroglyphic decipherment. At first they briefly cooperated in their work, but later, from around 1815, a chill arose between them. For many years they kept details of their work away from each other.

Some of Young's conclusions appeared in the famous article "Egypt" he wrote for the 1818 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.

When Champollion in 1822 published a translation of the hieroglyphs and the key to the grammatical system, Young (and many others) praised his work. Nevertheless, in 1823, Young published an Account of the Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphic Literature and Egyptian Antiquities, to have his own work recognised as the basis for Champollion's system.

Young had correctly found the sound value of six hieroglyphic signs, but had not deduced the grammar of the language. Young, himself, acknowledged that he was somewhat at a disadvantage because Champollion's knowledge of the relevant languages, such as Coptic, was much greater.[27]

Several scholars have suggested that Young's true contribution to Egyptology was his decipherment of the demotic script. He made the first major advances in this area; he also correctly identified demotic as being composed by both ideographic and phonetic signs.[28]

Subsequently, Young felt that Champollion was unwilling to share the credit for the decipherment. In the ensuing controversy, strongly motivated by the political tensions of that time, the British tended to champion Young, while the French mostly championed Champollion.

In England, while Sir George Lewis still doubted Champollion's achievement as late as 1862, others were more friendly. For example, Reginald Poole, and Sir Peter Le Page Renouf both defended Champollion.[29]

Champollion did acknowledge some of Young's contribution, but rather sparingly. However, after 1826, when Champollion was a curator in the Louvre, he did offer Young access to demotic manuscripts.[30]

Music

He developed Young temperament, a method of tuning musical instruments.

Religious views

Though he sometimes dealt with religious topics of history in Egypt and wrote about the history of Christianity in Nubia, not much is known about Young's personal religious views.[31] On George Peacock's account, Young never spoke to him about morals, metaphysics or religion, though according to Young's wife, his attitudes showed that "his Quaker upbringing had strongly influenced his religious practices."[32] Authority sources have described Young in terms of a cultural Christian Quaker.[33][34]

Hudson Gurney informed that before his marriage, Young had to join the Church of England, and was baptized later. After his work on physics received some criticism from Henry Brougham, Young stated: "I have resolved to confine my studies and my pen to medical subjects only. For the talents which God has not given me, I am not responsible, but those which I possess, I have hitherto cultivated and employed as diligently as my opportunities have allowed me to do ; and I shall continue to apply them with assiduity, and in tranquillity, to that profession which has constantly been the ultimate object of all my labours.[35]

Gurney stated that Young "retained a good deal of his old creed, and carried to his scriptural studies his habit of inquisition of languages and manners," rather than the habit of proselytism.[36] Yet, the day before his death, Young participated in religious sacraments; as reported in David Brewster's Edinburgh Journal of Science: "After some information concerning his affairs, and some instructions concerning the hierographical papers in his hands, he said that, perfectly aware of his situation, he had taken the sacraments of the church on the day preceding... His religious sentiments were by himself stated to be liberal, though orthodox. He had extensively studied the Scriptures, of which the precepts were deeply impressed upon his mind from his earliest years; and he evidenced the faith which he professed; in an unbending course of usefulness and rectitude."[37]

Selected writings

- A Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts (1807, republished 2002 by Thoemmes Press).

- Miscellaneous Works of the Late Thomas Young, M.D., F.R.S. (1855, 3 volumes, editor John Murray, republished 2003 by Thoemmes Press).

- Œuvres Complètes, Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1866.

References

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography

- 1 2 Robinson, Andrew (2007). The Last Man Who Knew Everything: Thomas Young, the Anonymous Genius who Proved Newton Wrong and Deciphered the Rosetta Stone, among Other Surprising Feats. Penguin. ISBN 0-13-134304-1.

- ↑ Singh, Simon (2000). The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography. Anchor. ISBN 0-385-49532-3.

- ↑ "Young, Thomas (YN797T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter Y" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Peacock, George (1855). Life of Thomas Young: M.D., F.R.S., &c.; and One of the Eight Foreign Associates of the National Institute of France. J. Murray.

- ↑ Samuel Austin Allibone (1871). A Critical Dictionary of English Literature: And British and American Authors, Living and Deceased, from the Earliest Accounts to the Middle of the Nineteenth Century. Containing Thirty Thousand Biographies and Literary Notices, with Forty Indexes of Subjects, Volume 3. J. B. Lippincott & Co. p. 2904.

- ↑ Wood, Alexander; Oldham, Frank (1954). Thomas Young Natural Philosopher 1773–1829. Cambridge University Press. p. 331.

- ↑ "Peacock's Life of Dr Young" by George Peacock, D.D., F.R.S., etc. Dean of Ely, Lowndean Professor of Astronomy University of Cambridge, etc. quoted in "The Living Age" by E. Littell, Second Series, Volume X, 1855, Littell, Son and Company, Boston.

- ↑ Buick, Tony (2010). The Rainbow Sky: An Exploration of Colors in the Solar System and Beyond. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 81. ISBN 9781441910530.

- ↑ "Thomas Young (1773–1829)". UC Santa Barbara. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Haidar, Riad. "Thomas Young and the wave theory of light" (PDF). Bibnum. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Young, Thomas (1804). "Bakerian Lecture: Experiments and calculations relative to physical optics". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 94: 1–16. Bibcode:1804RSPT...94....1Y. doi:10.1098/rstl.1804.0001.

- ↑ Shamos, Morris (1959). Great Experiments in Physics. New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston. pp. 96–101.

- ↑ Magie, William Francis (1935). A Source Book in Physics. Harvard University Press. p. 309

- ↑ Of course, both Young and Newton were eventually shown to be partially correct, as neither wave nor particle explanations alone can explain the behaviour of light. See e.g. http://www.single-molecule.nl/notes/light-waves-and-photons/.

- ↑ Young, Thomas (1845). Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts. London: Taylor and Walton.

- ↑ Truesdell, Clifford A. (1960). The Rational Mechanics of Flexible or Elastic Bodies, 1638–1788: Introduction to Leonhardi Euleri Opera Omnia, vol. X and XI, Seriei Secundae. Orell Fussli.

- ↑ "Structures, or Why Things Don't Fall Down" by J. E. Gordon, Penguin Books, 1978.

- ↑ Young, Thomas (1801). "On the mechanics of the eye". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 91: 23. Bibcode:1801RSPT...91...23Y. doi:10.1098/rstl.1801.0004.

- ↑ Young, T. (1802). "Bakerian Lecture: On the Theory of Light and Colours". Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 92: 12–48. doi:10.1098/rstl.1802.0004.

- ↑ Young, Thomas (1805). "An Essay on the Cohesion of Fluids". Phil. Trans: 65. JSTOR 107159. doi:10.1098/rstl.1805.0005.

- ↑ Fechner, Gustav Theodor (1878). Ueber den Ausgangswerth der kleinsten Absweichungssumme. S. Hirzel.

- ↑ Tijsseling, A.S., Anderson, A. (2008). "Thomas Young's research on fluid transients: 200 years on". Proc. of the 10th Int. Conf. on Pressure Surges (Editor S. Hunt), Edinburgh, United Kingdom, pp. 21–33. BHR Group. ISBN 978-1-85598-095-2.

- ↑ E.A.W. Budge, [1893], The Rosetta Stone. www.sacred-texts.com p132

- ↑ Young's first publications are as follows: "Letter to the Rev. S. Weston respecting some Egyptian Antiquities". With four copper plates [published under the name of his friend William Rouse Boughton, but written by Young], Archeologia Britannica. London, 1814. Vol. XVIII. P. 59-72; [Anonymous publication], Museum Criticum of Cambridge, Pt. VI., 1815 (this includes the correspondence which took place between Young, Silvestre de Sacy and Akerblad)

- ↑ Singh, Simon. "The Decipherment of Hieroglyphs". BBC. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Adkins & Adkins 2000, p. 277.

- ↑ Thomasson 2013.

- ↑ "Jean-François Champollion". Great Historians. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ↑ Wood, Alexander. 2011. Thomas Young: Natural Philosopher 1773–1829. Cambridge University Press. p. 56

- ↑ Wood, Alexander. 2011. Thomas Young: Natural Philosopher 1773–1829. Cambridge University Press. p. 329

- ↑ Peacock & Leitch., Miscellaneous works of the late Thomas Young (1855), London, J. Murray, p. 516: "he was pre-eminently entitled to the high distinction of a Christian, patriot, and philosopher."

- ↑ Wood, Alexander. 2011. Thomas Young: Natural Philosopher 1773–1829. Cambridge University Press. p. XVI

- ↑ Wood, Alexander. 2011. Thomas Young: Natural Philosopher 1773–1829. Cambridge University Press. p. 173

- ↑ Wood, Alexander. 2011, p. 56

- ↑ Brewster, David. 1831. The Edinburgh Journal of Science. Vol. 8, Blackwood. pp. 204;207

Further reading

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy (2000). The Keys of Egypt: The Obsession to Decipher Egyptian Hieroglyphs. Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-019439-1.

- Barr, E. Scott (1963). "Men and Milestones in Optics. II. Thomas Young". Applied Optics. 2 (6): 639–647. Bibcode:1963ApOpt...2..639B. doi:10.1364/AO.2.000639.- The link is to a pdf version of the paper.

- Robinson, Andrew (2005). "A Polymath's Dilemma". Nature. 438 (7066): 291. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..291R. PMID 16292291. doi:10.1038/438291a.

- Robinson, Andrew (April 2006). "Thomas Young: The Man Who Knew Everything". History Today. 56: 53–57.

- Robinson, Andrew (2006). The Last Man Who Knew Everything: Thomas Young, the Anonymous Polymath Who Proved Newton Wrong, Explained How We See, Cured the Sick and Deciphered the Rosetta Stone. New York: Pi Press. ISBN 0-13-134304-1.

- Reviewed by Nicholas Shakespeare in The Telegraph, 24 September 2006.

- Reviewed by Michael Bywater in The New Statesman, 13 November 2006.

- Reviewed by Simon Singh in The Telegraph, 26 November 2006.

- Reviewed by Rosemary Hill in The Times, 10 December 2006.

- Reviewed by PD Smith in The Guardian, 20 January 2007.

- Saslow, Wayne (2002). Electricity, Magnetism, and Light. Toronton: Thomson Learning. ISBN 0-12-619455-6.- Discusses Young's theoretical and experimental work on interference

- Thomasson, Fredrik (2013). The Life of J. D. Åkerblad: Egyptian Decipherment and Orientalism in Revolutionary Times. BRILL.

- Wood, Alex; Oldham, Frank (1954). Thomas Young. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Young, Thomas (1823). An Account of Some Recent Discoveries in Hieroglyphical Literature and Egyptian Antiquities. London: John Murray. Young's account of his hieroglyphic research. (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01716-9)

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Young, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Young, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Young (scientist). |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Young (scientist) |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas Young Davis |

- ABC Radio International program (Ockham's Razor) on Thomas Young – available for download and streaming (as of 9 July 2006)

- Young's 1802 Royal Institution lectures, published 1809, for online or .pdf reading. Available 2 November 2014.