Thomas Wedgwood (photographer)

.jpg)

Thomas Wedgwood (14 May 1771 – 10 July 1805), son of Josiah Wedgwood, the potter, is most widely known as an early experimenter in the field of photography.

He is the first person known to have thought of creating permanent pictures by capturing camera images on material coated with a light-sensitive chemical. His practical experiments yielded only shadow image photograms that were not light-fast, but his conceptual breakthrough and partial success have led some historians to call him "the first photographer".[1][2][3]

Life

Thomas Wedgwood was born in Etruria, Staffordshire, now part of the city of Stoke-on-Trent in England.

Wedgwood was born into a long line of pottery manufacturers, grew up and was educated at Etruria and was instilled from his youth with a love for art. He also spent much of his short life associating with painters, sculptors, and poets, to whom he was able to be a patron after he inherited his father's wealth in 1795.

As a young adult, Wedgwood became interested in the best method of educating children, and spent time studying infants. From his observations, he concluded that most of the information that young brains absorbed came through the eyes, and were thus related to light and images.

Wedgwood never married and had no children. His biographer notes that "neither his extant letters nor family tradition tell us of his caring for any woman outside the circle of his relations" and that he was "strongly attracted" to musical and sensitive young men.

In imperfect health as a child and a chronic invalid as an adult, he died in the county of Dorset at the age of 34.

A pioneer of photography

Wedgwood is the first person reliably documented to have used light-sensitive chemicals to capture silhouette images on durable media such as paper, and the first known to have attempted to photograph the image formed in a camera obscura.

The date of his first experiments in photography is unknown, but he is believed to have indirectly advised James Watt (1736–1819) on the practical details prior to 1800. In a letter that has been variously dated to 1790, 1791 and 1799, Watt wrote to Josiah Wedgwood:

Dear Sir, I thank you for your instructions as to the Silver Pictures, about which, when at home, I will make some experiments...

In his many experiments, possibly with advice on chemistry from his tutor Alexander Chisholm and members of the Lunar Society, Wedgwood used paper and white leather coated with silver nitrate. The leather proved to be more light-sensitive. His primary objective had been to capture real-world scenes with a camera obscura, but those attempts were unsuccessful. He did succeed in using exposure to direct sunlight to capture silhouette images of objects in contact with the treated surface, as well as the shadow images cast by sunlight passing through paintings on glass. In both cases, the sunlit areas rapidly darkened while the areas in shadow did not.

Wedgwood met a young chemist named Humphry Davy (1778–1829) at the Pneumatic Clinic in Bristol, while Wedgwood was there being treated for his ailments. Davy wrote up his friend's work for publication in London’s Journal of the Royal Institution (1802), titling it “An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver, with observations by Humphrey Davy. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq.” The paper was published and detailed Wedgwood’s procedures and accomplishments, as well as Davy's own variations of them. In 1802 the Royal Institution was not the venerable force it is today and its Journal was:

a little paper printed from time to time to let the subscribers to the infant institution know what was being done ...the 'Journal' did not live beyond a first volume. There is nothing to show that Davy's account was ever read at any meeting; and the print of it would have been read, apparently, if read at all, only by the small circle of members and subscribers to the institution, of whom, we may be pretty sure, only a small minority can have been scientific people.[4]

Nevertheless, the paper of 1802 and Wedgwood's work directly influenced other chemists and scientists delving into the craft of photography, since subsequent research (Batchen, p. 228) has shown it was actually quite widely known about and was mentioned in chemistry textbooks as early as 1803. David Brewster, later a close friend of photography pioneer Henry Fox Talbot, published an account of the paper in the Edinburgh Magazine (Dec 1802). The paper was translated into French, and also printed in Germany in 1811. J. B. Reade's work in 1839 was directly influenced by reading of Wedgwood's more rapid results when using leather. Reade tried treating paper with a tanning agent used in making leather and found that after sensitization the paper darkened more rapidly when exposed. Reade's discovery was communicated to Talbot by a friend, as was later proven in a court case over patents.

The account given by Reade of his experiments was entirely retrospective. His recollection was shown to have been in error, made in 1840 and not 1839, drawn from recollections he made in 1851, more than ten years after.</ref> See R. D. Wood "J.B.Reade, FRS., and the early History of Photography, part II Gallic Acid and Talbot's Calotype Patent", from The Annals of Science Vol.27, No.1, March, 1971</ref>

There are two additional points relevant to Reade's erroneous claim: he was discussing the use of Gallic acid with silver nitrate. Silver nitrate is not a halide and unlike the nitrate, chloride and fluoride of silver. It has not the potential to develop the latent image. In addition Reade failed to understand or to make a distinction between tannic acid and gallic acid, referring to either "tincture, infusion of, or a decoction of galls" and gallic acid as though all were interchangeable. Any of these solutions would contain little more than 3% gallic acid, which is relatively slow acting. Tannic acid, on the other hand, which constitutes between 60 and 79% is fast acting. The result being that it would immediately act upon any gelatine present to render it insoluble; hence its use, since time immemorial, to tan leather which is a strategic material (ie.,for solder's boots, and harness to attach guns to gun-carriages etc). Talbot would have known of this group of organic compounds and there is evidence that he had experimented with gallic acid (2-3-4 tri-hydronitrobenzoic acid) since 1835 at the latest. First synthesised by Carl William Scheele in 1786 whose studies were widely known (earlier, in fact if you reference his experiments with secret writing).[5] Reade's images darkened quickly because the tannic acid component of the"extract of galls" has the power to spontaneously reduce silver nitrate to its metallic state .

Wedgwood was unable to "fix" his pictures to make them immune to the further effects of light. Unless kept in complete darkness, they would slowly but surely darken all over, eventually destroying the image. As Davy put it in his paper of 1802, the picture,

immediately after being taken, must be kept in some obscure place. It may indeed be examined in the shade, but in this case the exposure should be only for a few minutes; by the light of candles and lamps, as commonly employed, it is not sensibly affected.

Rumours of surviving photographs

Although unfixed, photographs such as Wedgwood made can be preserved indefinitely by storing them in total darkness and protecting them from the harmful effects of prolonged open exposure to the air—for example, by keeping them tightly pressed between the pages of a larger book.

In the middle to late 1830s, both Henry Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre found ways of chemically stabilizing the images their processes produced, making them relatively insensitive to additional exposure to light. In 1839, John Herschel pointed out his earlier published discovery that hyposulphite of soda (now known as sodium thiosulfate but still nicknamed "hypo") dissolved silver halides. This allowed the remaining light-sensitive silver salts to be completely washed away, truly "fixing" the photograph. Herschel also found that in the case of silver nitrate, a thorough washing with plain water sufficed to remove the unwanted remainder from paper—at least, the type of paper Herschel used—but only if the water was very pure.

In 1885, Samuel Highley, an early photography historian, published an article in which he remarked that he had seen what must have been unfixed examples of early pictures made by Wedgwood, presumably dating to the 1790s. His was only one of several latter 19th century claims alleging the current or former existence of improbably early photographs, usually based on decades-old memories or depending on questionable assumptions, which investigators determined to be unverifiable, unreliable or definitely mistaken.[6]

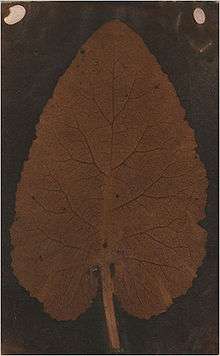

In 2008, there were widespread news reports that one of Wedgwood's photographs had surfaced and was about to be sold at auction. The photogram, as shadow photographs are now called, showed the silhouette and internal structure of a leaf and was marked in one corner with what appeared to be the letter "W". Originally unattributed, then attributed to Talbot, an essay by Talbot expert Larry Schaaf, included in the auction catalog, rejected that attribution but suggested that it could actually be by Thomas Wedgwood and date from the 1790s.[7] An authentic Wedgwood image would be a key historical relic, avidly sought by collectors and museums, and would probably sell for a seven-figure price at auction. Considerable controversy erupted after the announcement and Schaaf's rationale for such an attribution was vigorously disputed by other respected photography historians. A few days before the scheduled sale, the image was withdrawn so that it could be more completely analyzed.[8]

If any special physical analysis was later done, the findings had not been made public as of mid-2015, when Schaaf presented some new discoveries which apparently solved the major mysteries and laid his unexpectedly sensationalized scholarly speculation to rest. The initial "W", it now seems, is that of William West, an entrepreneur who was selling packets of "photogenic drawing paper" to the public only weeks after instructions for its preparation were unveiled by its inventor, Talbot, early in 1839.[9] The image was probably created that same year by Sarah Anne Bright, a previously unknown amateur.[10]

Patronage of Coleridge

Wedgwood was a friend of the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and arranged for him to have an annuity of £150 in 1798 so Coleridge could devote himself to philosophy and poetry. According to an 1803 letter, Coleridge even attempted to procure cannabis for Wedgwood to alleviate his chronic stomach aches.[11]

References

Notes

- ↑ e.g. Litchfield, book title et al.

- ↑ Talbot, W.H.F. (1844). The Pencil of Nature, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, London, 1844. On page 11, Talbot acknowledges that the original 1802 account of Wedgwood and Davy's experiments, which he did not see until his own experiments were well underway, "...certainly establishes their claim as the first inventors of the Photographic Art, though the actual progress they made in it was small."

- ↑ "Thomas Wedgwood | British physicist". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-01-24.

- ↑ Litchfield, pp. 196-197.

- ↑ Mike Weaver, Henry Fox Talbot; Selected Texts and Bibliography (Oxford: Clio Press, Ltd., 1992): Michael Gray, Secret Writing

- ↑ Litchfield, appendix C.

- ↑ An Image Is a Mystery for Photo Detectives, Randy Kennedy. New York Times, April 17, 2008.

- ↑ E-Photo Newsletter, Issue 148, 9/28/2008. See first two articles by Alex Novak and Michael Gray. Retrieved 7 May 2013.

- ↑ Schaaf, Larry. (2015). "More on 'The Damned Leaf'". Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ Schaaf, Larry. (2015). "Tempestuous Teacups and Enigmatic Leaves". Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ Coleridge Letters

Bibliography

- Litchfield, Richard Buckley (1903). Tom Wedgwood, the first photographer; an account of his life, his discovery and his friendship with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, including the letters of Coleridge to the Wedgwoods and an examination of accounts of alleged earlier photographic discoveries. London, Duckworth and Co. Public domain, available free at archive.org. (Includes the unabridged text of Humphry Davy's 1802 paper.)

Further reading

- Batchen, Geoffrey (1999). Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography. MIT Press.

- Gregory, R.L. (2005). "Accentuating the negative: Tom Wedgwood (1771 - 1805), photography and perception". Perception 34 (5), pages 513–520.