Tom Sayers

| Tom Sayers | |

|---|---|

Tom Sayers, early hand-tinted photograph, circa 1860. | |

| Born |

25 May 1826 Brighton, England |

| Died |

8 November 1865 (aged 39) Camden Town, London, England Buried Highgate Cemetery West Section; London, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Height | 5 ft 8 in (173 cm) |

| Weight | 150 lb (68 kg; 10 st 10 lb) |

| Years active | 1849-1860 |

| Professional boxing record | |

| Total | 16 |

| Wins | 12 |

| Losses | 1 |

| Draws | 3 |

Tom Sayers (15 or 25 May[1] 1826 – 8 November 1865) was an English bare-knuckle prize fighter. There were no formal weight divisions at the time, and although Sayers was only five feet eight inches tall and never weighed much more than 150 pounds, he frequently fought much bigger men. In a career which lasted from 1849 until 1860, he lost only one of sixteen bouts.

His lasting fame depends exclusively on his final contest, when he faced American champion John Camel Heenan[2] in a battle which was widely considered to be boxing’s first world championship. It ended in chaos when the spectators invaded the ring, and the referee finally declared a draw.

Regarded as a national hero, Sayers, for whom the considerable sum of £3,000 was raised by public subscription, then retired from the ring. After his death five years later at the age of 39, a huge crowd watched his cortège on its journey to London’s Highgate Cemetery.

Early years

Tom Sayers was born in May 1826 in a slum in the Brighton alley of Pimlico (now Tichborne Street) not far from the Royal Pavilion. He was the youngest of the five children of William[3] Sayers (33), a shoemaker, and his wife Maria, ten years her husband’s senior. At the age of six, Tom became a Jack in the Water, earning a few coppers performing small duties for holidaymakers and fishermen on Brighton beach. Claims that he attended school in 1836 may be unfounded,[4] and he was barely literate.

At the age of thirteen, he went to London, where he stayed with his sister Eliza and her husband Robert King, a builder. Sayers became a bricklayer, and for the next seven years shuttled between his home town and the capital. He is known to have worked on the London Road viaduct outside Brighton, and may well have taken part in the construction of London’s King’s Cross Station. In 1846, he finally settled in the capital, taking up residence in the notorious slum of Agar Town, just north of where St Pancras Station now stands.

It was around 1847 that he set up home in a more salubrious part of Camden Town with Sarah Henderson.[5] Only fifteen years old, Sarah was unable to marry without her father’s permission, and her daughter Sarah (1850-1891), and son Tom (1852-1936)[6] by Sayers were consequently illegitimate.

Prize ring career

Although the prize ring had long been illegal, it continued as an underground activity, and Sayers, having earned a considerable reputation from a number of informal fights, decided to try to make a living with his fists. His first contest as a professional was in March 1849, when he defeated Abe Couch (or Crouch).

In 1853, after three more victories, he challenged Nat Langham, who, despite the absence of formal weight divisions, was widely accepted as England’s middleweight champion. This was Sayers's toughest fight so far, and a combination of illness and inexperience contributed to his first and only defeat. The wily Langham gained the upper hand by temporarily blinding his opponent with frequent blows to the eyes.

Still, Sayers had fought well, and defeat did not damage his career. But his marriage that same year to Sarah Henderson, by now old enough to marry without her father’s permission, was soon in ruins as she left to live with another man. To make matters worse, on top of an expensive failure to set himself up as a publican, he had great difficulty arranging another payday in the ring: after one further victory, men of his own size considered him just too dangerous.

Finally and in desperation, he took the bold step of challenging a leading heavyweight. The convention – though it was never a formal rule – was that men fought others of their own size, and few gave him much chance against the highly regarded Harry Paulson.[7] Sayers, however, was undaunted, and in January 1856, a convincing victory raised him to a new level.

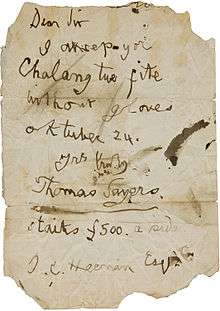

Thus it was that the following year he fought Bill Perry, the Tipton Slasher, for the national championship. Although written off by most of the experts, Sayers won comfortably, and went on to defeat several more opponents before accepting in 1859 a challenge from US champion John Camel Heenan known as the Benicia Boy.

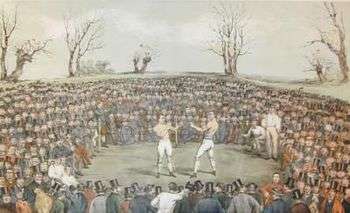

The big fight

By this time the prize ring was in utter disrepute – and virtually ignored by everyone outside the ranks of the Fancy, as the followers of boxing were known – yet the Sayers–Heenan fight caught the public imagination on both sides of the Atlantic. In the words of The Times, "this challenge has led to an amount of attention being bestowed on the prize ring which it has never received before",[8] while in America, the New York Clipper observed that "‘Whate’er we do, where’er we be,’ fight, fight, fight is the topic that engrosses all attention".[9]

Efforts of a number of concerned citizens to have the illegal event prevented came to nothing, and the battle took place at Farnborough in Hampshire on the morning of Tuesday, 17 April 1860. It was on the face of it an unequal contest: Sayers was conceding forty pounds in weight, five inches in height and eight years in age.

To make matters worse, his right arm was damaged early in the action, and he had to fight one-handed for most of a ferocious contest which went on for more than two hours. Heenan, however, was also handicapped, Sayers having succeeded in closing his right eye, and making of his whole face a bloody mess.

After more than forty rounds, the fight ended in chaos when Heenan illegally tried to strangle Sayers, the ropes were cut, the crowd invaded the ring, and police moved in to put a stop to proceedings. The referee finally declared a draw, but hostilities continued for some weeks outside the ring, with the American camp claiming that Heenan had been cheated of victory, and the British insisting that Sayers had been on top.

According to Iain Manson, a careful study of newspaper reports of the fight and the subsequent controversy[10] leaves little doubt that Heenan was on the verge of victory when the action was stopped. Others say the match was a draw. However, according to Alan Wright's book "Tom Sayers: the last great bareknuckle champion", Heenan's attempted strangling of Sayers did not stop the fight, nor did the subsequent invasion of the ring by Sayers' supporters. This account says that order was nearly restored and the ring re-pitched yards away. The fight continued for four or five rounds with neither man able to box proficiently. When the Police were spotted at the edge of the field, the entire throng, including the fighters, made a bolt for it and the fight ended there.

Differences between the two men were finally patched up, and both were awarded a championship belt. The tour of England, Ireland and Scotland which they then undertook together was, however, only a partial success. The two men had become firm friends and when Heenan returned to England in 1863 to fight the then champion Tom King, he ensured that Tom Sayers was in his corner. It seemed a wise decision at the time as Sayers had been a meticulous and dedicated trainer all his career, unusual for the time. Sayers was also considered a first class ring-tactician. Jem Mace would often cite Sayers' ring methods when he turned to coaching. However, the move turned out to be a disaster. Tom Sayers offered no help at all to Heenan during his fight with King. One journalist claimed that Tom just stood looking at Heenan with a vacant, wide-eyed look as if he didn't quite know where he was. It is likely that this torpor was the result of untreated diabetes. Heenan fell mysteriously ill during the fight and conceded to King. Heenan felt he had been drugged and blamed Sayers for his lack of diligence and contribution. The two men never spoke again.

Retirement and death

Tom Sayers never fought again. A public subscription was raised for him after the fight, and he received the sum of £3,000, enough to fund a comfortable retirement. It was fortunate for him that this money was safely invested, or he might have been ruined by his unwise decision to go into the circus business.

He had by this time begun living with another woman, but the relationship broke up in acrimony, and his final years were marred by diabetes, tuberculosis and heavy drinking. As with all those who suffer from years of untreated diabetes, his personality changed dramatically. Graham Gordon, in his book "Jem Mace: master if the ring", Tom Sayers became loudly bitter and abusive as well as surly and confrontational, alienating those that had been loyal to him. He died at No. 257 Camden High Street on 8 November 1865,[11] and his funeral a week later attracted some 100,000 people[12] to Camden Town.

Misfortune pursued him beyond the grave. His estranged (but not divorced) wife, who now had three sons by the man for whom she had left him, went to court to disinherit her two children by Sayers. The parents’ subsequent marriage had not changed their legal status, and a judge ruled that, while they were certainly illegitimate, it could not be proved that Sayers was not the father of his wife’s other three children. These must therefore be regarded as legitimate, and entitled to inherit his estate.[13]

Tom Sayers is buried in Highgate Cemetery, his tomb guarded by the stone image of his mastiff, Lion, who was chief mourner at his funeral. The house in Camden where he died now has an English Heritage blue plaque.[14]

Career record

| 12 Wins, 1 Loss, 3 Draws | |||||||

| Result | Opponent | Date | Location | Duration[15] | |||

| Win | Abe Couch | 1849-03-19 | Greenhithe, Kent | 13 minutes (6 rounds) | |||

| Draw | Dan Collins | 1850-10-22 | Edenbridge, Kent | 1 hour 52 minutes (39 rounds) | |||

| Win | Dan Collins | 1851-04-29 | Long Reach, Kent | 1 hour 24 minutes (44 rounds) | |||

| Win | Jack Grant | 1852-06-29 | Mildenhall, Suffolk | 2 hours 30 minutes (64 rounds) | |||

| Win | Jack Martin | 1853-01-26 | Long Reach, Kent | 55 minutes (23 rounds) | |||

| Loss | Nat Langham | 1853-10-18 | Lakenheath, Suffolk | 2 hours 2 minutes (60 rounds) | |||

| Win | George Sims | 1854-02-28 | Long Reach, Kent | 5 minutes (4 rounds) | |||

| Win | Harry Paulson | 1856-01-29 | Appledore, Kent | 3 hours, 8 minutes (109 rounds) | |||

| Draw | Aaron Jones | 1857-01-06 | Canvey Island, Essex | 3 hours (62 rounds) | |||

| Win | Aaron Jones | 1857-02-10 | Canvey Island, Essex | 2 hours (85 rounds) | |||

| Win | Bill Perry | 1857-06-16 | Isle of Grain, Kent | 1 hour 15 minutes (10 rounds) | |||

| Win | Bill Benjamin | 1858-01-05 | Isle of Grain, Kent | 7 minutes (3 rounds) | |||

| Win | Tom Paddock | 1858-06-15 | Canvey Island, Essex | 1 hour 20 minutes (21 rounds) | |||

| Win | Bill Benjamin | 1859-04-05 | Isle of Grain, Kent | 22 minutes (11 rounds) | |||

| Win | Bob Brettle | 1859-09-20 | Ashford, Kent | 15 minutes (7 rounds) | |||

| Draw | John C. Heenan | 1860-04-17 | Farnborough, Hampshire | 2 hours 10 minutes (42 rounds) | |||

In fiction

A fictionalised Tom Sayers appeared in a series of weekly adventures penned for the story paper The Marvel by Amalgamated Press writer Arthur S Hardy (real name Arthur Joseph Steffens,[16] b. 28 September 1873) in the first decade of the twentieth century. Hardy's version of Sayers was an Edwardian actor-manager, touring Britain's theatres and music halls with staged recreations of his boxing triumphs in a career move very loosely based on the real Sayers's circus venture. This romanticised figure was revived and further developed as a central character in The Kingdom of Bones, a 2007 novel by Stephen Gallagher.

Tom Sayers appears in George du Maurier's first novel Peter Ibbetson (Part Two).

Notes

- ↑ Both dates have been suggested, but there is no firm evidence either way.

- ↑ The Times, 6 January 1864. "Carmel" is an erroneous spelling of Heenan’s middle name.

- ↑ Marriage certificate of Thomas Sayers and Sarah Henderson, St Peter’s Church, Islington, Middlesex, dated 8 March 1853. This ends the uncertainty regarding the first name of Sayers senior.

- ↑ For the case that Sayers attended school, see Middle Street School.

- For the case against, see Manson, p. 28.

- ↑ Marriage certificate of Thomas Sayers and Sarah Henderson, St Peter’s Church, Islington, Middlesex, dated 8 March 1853. The claim that he married a widow named Sarah Powell is without foundation.

- ↑ Sarah Sayers birth certificate, registered 10 July 1850; Tom Sayers birth certificate, registered 7 October 1852. Sarah Mensley (married name) death certificate registered 6 March 1891; Tom Sayers death certificate registered 27 January 1936

- ↑ Manson, p. ix. "Paulson" rather than "Poulson" was the version preferred by the man himself.

- ↑ The Times, 18 April 1860.

- ↑ New York Clipper, 31 March 1860.

- ↑ Manson, pp. 222–223.

- ↑ 257 High Street was the Mensley Boot and Shoe Manufacturers, owned by John Mensley, where Tom had his boots made. Tom's daughter, Sarah, married John's younger brother George Mensley

- ↑ Brooks, p. 5. The oft-quoted figure of 10,000 is wrong.

- ↑ reported in The Times, 21 April 1868 (http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/archive/frame/article/1868-04-21/10/6.html)

- ↑ "Blue plaque - Tom Sayers". openplaques.org. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Sources frequently differ over the duration of a contest and the number of rounds. See Manson, pp. 275–276 (Endnote 17).

- ↑ The FictionMags Index, series list

Further reading

- Brooks, Chris. Burying Tom Sayers. Annual of The Victorian Society, 1989.

- Gallagher, Stephen. The Kingdom of Bones. Random House/Shaye Areheart Books, 2007.

- Langley, Tom. The Life of Tom Sayers. Vance Harvey Publishing, 1973.

- Lloyd, Alan. The Great Prize Fight. Cassell, 1977.

- Manson, Iain. The Lion and the Eagle. SportsBooks, 2008.

- Wright, Alan. Tom Sayers: the last great bare-knuckle champion. The Book Guild, 1994.