Thomas Palaiologos

| Thomas Palaiologos | |

|---|---|

| Despot of the Morea | |

| |

| Reign | 1428–1460 |

| Predecessor | Constantine Palaiologos |

| Born | 1409 |

| Died | 12 May 1465 (aged 55) |

| Spouse | Catherine Zaccaria |

| Issue |

Helena Andreas Manuel Sophia-Zoe |

| Dynasty | Palaiologos |

| Father | Manuel II Palaiologos |

| Mother | Helena Dragaš |

| Signature |

|

Thomas Palaiologos or Palaeologus (Greek: Θωμᾶς Παλαιολόγος Thomas Palaiologos; 1409 – 12 May 1465) was Despot in Morea from 1428 until the Ottoman conquest in 1460. After the desertion of his older brother to the Turks in 1460, Thomas Palaiologos became the legitimate claimant to the Byzantine throne, a claim he maintained during his exile in Italy.

Life

Thomas Palaiologos was the youngest surviving son of the Byzantine Emperor[1][2][3] Manuel II Palaiologos [4] and his wife Helena Dragaš. His maternal grandfather was Constantine Dragaš. His brothers included the Byzantine emperors John VIII Palaiologos[5] and Constantine XI Palaiologos, as well as Theodore II Palaiologos and Demetrios Palaiologos, Despots of the Morea, and Andronikos Palaiologos, Despot of Thessalonica. As youngest son, Thomas was never expected to reign, but his children became the only surviving heirs of the defunct Palaiologan dynasty.

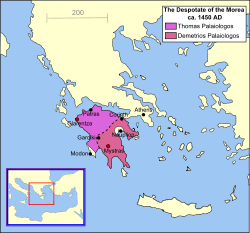

Like other imperial sons, Thomas Palaiologos was made a Despot (despotēs), and from 1428 joined his brothers Theodore and Constantine in the Morea. After the retirement of Theodore during 1443, he governed together with Constantine, until the latter became emperor (as Constantine XI) during 1448. Thomas remained Despot of the Morea, but was forced to share the rule with his older brother Demetrios beginning 1449. The Byzantine possessions in Morea had expanded considerably at the expense of the Latin Principality of Achaea. After the last war during 1430 virtually the entire peninsula was ruled by the Byzantines, and Thomas married Catherine Zaccaria, the daughter of the last Prince of Achaea Centurione II Zaccaria, succeeding to his father-in-law's possessions during 1432.

After this period of success, the fortunes of Byzantine Morea decreased, as the collegiate government by several brothers caused increasing confusion. This became especially serious after the arrival of Demetrios, who had a pro-Ottoman policy as opposed to Thomas' pro-western orientation. From 1447 the Despots had become vassals of the Ottoman Sultan. At the beginning of the siege of Constantinople by Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire, an Ottoman army was sent with orders to raid in the Morea, preventing help from being sent to Constantinople. After the conquest of Constantinople by Mehmed II on 29 May 1453, to maintain the status quo, the Sultan ordered the two brothers to continue as joint rulers of Morea.

This order had been accepted for the first two years because of the Kantakouzenos family's revolt which started during the siege of Constantinople (1453) by Demetrios I Kantakouzenos' grandchild Manuel. Only during the next year did the forces of the Palaiologos brothers destroy the rebel forces.

In these circumstances, and without Constantine XI to maintain peace in the family, Thomas sought western aid against both the Ottomans and his pro-Ottoman brother Demetrios. He allied with Republic of Genoa and the Pope and defeated Demetrios, who fled seeking help from the Ottomans during 1460. The Ottoman army duly attacked Morea and quickly breached the Hexamilion wall across the Isthmus of Corinth, which was too long to be effectively manned and defended by Thomas' forces. Thomas escaped with his family to Italy, where he had already been recognized as the legitimate heir to the Byzantine Empire by the Pope.

The commanders of the garrisons of the fortified cities in Morea, deserted by their rulers, chose individually whether to fight or surrender, depending on their own will and circumstances. During the next year Graitzas received an offer to become general of the Republic of Venice, which he accepted, thus leaving Salmenikos to the Ottomans.

Imperial heirs

After the conquest of Morea, Thomas lived in Rome, recognized throughout Christian Europe as the rightful Emperor of the East. To create greater support for his situation Thomas changed his religion to Roman Catholicism from Greek Orthodoxy during his last years of life. After his death in 1465, the position of rightful Byzantine emperor was inherited by his older son Andreas Palaiologos, born in Mistra around 1453.

Mehmed II conquered the Empire of Trebizond, de facto the last free territory of the ancient Roman state, during the year 1461. Nevertheless, Mehmed had already proclaimed himself "Roman Emperor" upon capturing Constantinople (1453).

In an effort to reunite the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church, Pope Paul II arranged during 1472 a marriage between the Catholic daughter of Thomas, Zoe Palaiologina (renamed Sophia), and Grand Prince Ivan III of Russia, with the hope of making Russia a Roman Catholic country. This attempt to unite churches failed. Nonetheless, because of this marriage, Moscow began in the next century its imperial policy of "third Rome". Moreover, Thomas' great-grandson was Ivan IV of Russia, the first emperor (tsar) of Russia to be crowned as such (the imperial title had already come into use by Ivan III and his son Vasili III of Russia). The last known descendant of Zoe/Sophia was Maria of Staritsa, wife of Livonia's king Magnus. She died in 1610.

Family

By his marriage with Catherine (Caterina) Zaccaria of Achaea, Thomas Palaiologos had at least four children:

- Helena Palaiologina, who married Despot Lazar II of Serbia.

- Andrew (Andreas) Palaiologos, who succeeded as claimant to the Byzantine throne.

- Manuel Palaiologos.

- Zoe Palaiologina (renamed Sophia), who married Grand Prince Ivan III of Russia.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Thomas Palaiologos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- General

- George Sphrantzes, The Fall of the Byzantine Empire, trans. Marios Philippides, Amherst MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1980. ISBN 0-87023-290-8

- Jonathan Harris, Greek Émigrés in the West, 1400-1520, Camberley: Porphyrogenitus, 1995. ISBN 1-871328-11-X

- Jonathan Harris 'A worthless prince? Andreas Palaeologus in Rome, 1465-1502', Orientalia Christiana Periodica 61 (1995), 537-54

- Donald M. Nicol, The Immortal Emperor, Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-521-41456-3.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993) [1972]. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople 1453, Cambridge University Press, 1965. ISBN 0-521-09573-5

- Citations

- ↑ The Oxford handbook of Byzantine studies, Elizabeth Jeffreys, John F. Haldon, Robin Cormack, Oxford University Press, 2008, p.292

- ↑ History of the Byzantine Jews: a microcosmos in the thousand year empire, Elli Kohen, University press of America, 2007, p.156

- ↑ Empire of magic: medieval romance and the politics of cultural fantasy, Geraldine Heng, Columbia University Press, 2003, p.152

- ↑

- ↑

| Thomas Palaiologos Palaiologos dynasty Born: 1409 Died: 12 May 1465 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Constantine Palaiologos |

Despot of the Morea 1428–1460 with Demetrios Palaiologos |

Ottoman conquest of the Morea |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Preceded by Constantine XI Palaiologos |

— TITULAR — Byzantine Emperor (formally "Emperor of Constantinople") 1453–1465 with Demetrios Palaiologos Reason for succession failure: Ottoman conquest of Constantinople ends the Byzantine Empire |

Succeeded by Andreas Palaiologos |