Popeye

| Popeye | |

|---|---|

|

Popeye and J. Wellington Wimpy in E. C. Segar's Thimble Theatre (August 20, 1933) | |

| Author(s) |

E. C. Segar (creator, 1919–1937, 1938) Robin Williams (1980 film) Voice actors William Costello (1933–1935) Detmar Poppen (1935–1936, radio only) Floyd Buckley (Be Kind To Animals, 1936–1937 radio appearances) Jack Mercer (1935–1945 and 1947–1984) Mae Questel (Shape Ahoy) Harry Foster Welch (1945–1947) Maurice LaMarche (1985–present) Billy West (Popeye's Voyage: The Quest for Pappy, Drawn Together, Minute Maid commercials) Keith Scott (Popeye and Bluto's Bilge-Rat Barges)[1] Scott Innes (commercials) Tom Kenny (2014 animation test)[2] |

| Website |

www |

| Current status / schedule | New strips on Sundays, reprints Monday through Saturday |

| Launch date | December 19, 1919 |

| End date | July 30, 1994 (date of last first-run daily strip, Sunday strips continue) |

| Syndicate(s) | King Features Syndicate |

| Publisher(s) | King Features Syndicate |

| Genre(s) | Humor, adventure |

Popeye the Sailor is a cartoon fictional character created by Elzie Crisler Segar.[3][4] [5]The character first appeared in the daily King Features comic strip, Thimble Theatre, on January 17, 1929, and Popeye became the strip's title in later years; Popeye has also appeared in theatrical and television animated cartoons.[4]

Segar's Thimble Theatre strip was in its 10th year when Popeye made his debut, but the one-eyed (left) sailor quickly became the main focus of the strip, and Thimble Theatre became one of King Features' most popular properties during the 1930s. After Segar's death in 1938, Thimble Theatre was continued by several writers and artists, most notably Segar's assistant Bud Sagendorf. The strip continues to appear in first-run installments in its Sunday edition, written and drawn by Hy Eisman. The daily strips are reprints of old Sagendorf stories.[4]

In 1933, Max Fleischer adapted the Thimble Theatre characters into a series of Popeye the Sailor theatrical cartoon shorts for Paramount Pictures. These cartoons proved to be among the most popular of the 1930s, and Fleischer—and later Paramount's own Famous Studios—continued production through 1957. These cartoon shorts are now owned by Turner Entertainment, a subsidiary of Time Warner, and distributed by its sister company Warner Bros. Entertainment.[6]

Over the years, Popeye has also appeared in comic books, television cartoons, arcade and video games, hundreds of advertisements,[4] and peripheral products (ranging from spinach to candy cigarettes), and the 1980 live-action film directed by Robert Altman, starring comedian Robin Williams as Popeye.

In an interview, Charles Schulz said "Popeye was a great favorite of mine...I think Popeye was a perfect comic strip, consistent in drawing and humor". [7] In 2002, TV Guide ranked Popeye #20 on its "50 Greatest Cartoon Characters of All Time" list.[8]

Fictional character and story

Differences in Popeye's story and characterization vary depending on the medium. Originally, Popeye got his strength from rubbing the head of the Whiffle Hen, changing to spinach by 1932.[9] Swee'Pea is definitively Popeye's ward in the comic strips, but he is often depicted as belonging to Olive Oyl in cartoons. The cartoons also occasionally feature members of Popeye's family who have never appeared in the strip, notably his lookalike nephews Peepeye, Pupeye, Pipeye, and Poopeye.

There is no absolute sense of continuity in the stories, although certain plot and presentation elements remain mostly constant, including purposeful contradictions in Popeye's capabilities. Popeye seems bereft of manners and uneducated, yet he is often depicted as capable of coming up with solutions to problems that seem insurmountable to the police or, most importantly, the scientific community. Popeye has, alternatively, displayed Sherlock Holmes-like investigative prowess (determining, for instance, that his beloved Olive was abducted by estimating the depth of the villains' footprints in the sand), scientific ingenuity (as his construction, within a few hours, of a "spinach-drive" spacecraft), or oversimplified (yet successful) diplomatic arguments (by presenting his own existence—and superhuman strength—as the only true guarantee of world peace at diplomatic conferences). Popeye's pipe also proves to be highly versatile. Among other things, it has served as a cutting torch, jet engine, propeller, periscope, and, of course, a whistle with which he produces his trademark toot. Popeye also on occasion eats spinach through his pipe, sometimes sucking in the can itself along with the contents. Since the 1970s, Popeye is seldom depicted using his pipe to smoke tobacco.[4]

Popeye's exploits are also enhanced by a few recurring plot elements. One is the love triangle among Popeye, Olive, and Bluto, and the latter's endless machinations to claim Olive at Popeye's expense. Another is his near-saintly perseverance in overcoming any obstacle to please Olive, who often renounces Popeye for Bluto's dime-store advances. She is the only character that Popeye will permit to give him a thumping. Finally, Popeye usually uncovers villainous plots by accidentally sneaking up on the antagonists as they brag about or lay out their schemes.

Thimble Theatre and Popeye comic strips

Thimble Theatre was cartoonist E. C. Segar's third published strip when it first appeared in the New York Journal on December 19, 1919. The paper's owner William Randolph Hearst also owned King Features Syndicate, which syndicated the strip. It did not attract a large audience at first, and at the end of its first decade appeared in only half a dozen newspapers.

In its early years, the strip featured characters acting out various stories and scenarios in theatrical style (hence the strip's name). It could be classified as a gag-a-day comic in those days.

Thimble Theatre's first main characters were the thin Olive Oyl and her boyfriend Harold Hamgravy. After the strip moved away from its initial focus, it settled into a comedy-adventure style featuring Olive, Ham Gravy, and Olive's enterprising brother Castor Oyl. Olive's parents Cole and Nana Oyl also made frequent appearances.

Popeye first appeared in the strip on January 17, 1929 as a minor character. He was initially hired by Castor Oyl and Ham to crew a ship for a voyage to Dice Island, the location of a casino owned by the crooked gambler Fadewell. Castor intended to break the bank at the casino using the unbeatable good luck conferred by stroking the hairs on the head of Bernice the Whiffle Hen. Weeks later, on the trip back, Popeye was shot many times by Jack Snork, a stooge of Fadewell's, but survived by rubbing Bernice's head. After the adventure, Popeye left the strip but, due to reader reaction, he was quickly brought back.[4]

The Popeye character became so popular that he was given a larger role, and the strip was expanded into many more newspapers as a result. Initial strips presented Olive as being less than impressed with Popeye, but she eventually left Ham Gravy to become Popeye's girlfriend and Ham Gravy left the strip as a regular. Over the years, however, she has often displayed a fickle attitude towards the sailor. Castor Oyl continued to come up with get-rich-quick schemes and enlisted Popeye in his misadventures. Eventually, he settled down as a detective and later on bought a ranch out West. Castor has seldom appeared in recent years.

In 1933, Popeye received a foundling baby in the mail, whom he adopted and named "Swee'Pea." Other regular characters in the strip were J. Wellington Wimpy, a hamburger-loving moocher who would "gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today" (he was also soft-spoken and cowardly; Vickers Wellington bombers were nicknamed "Wimpys" after the character); George W. Geezil, a local cobbler who spoke in a heavily affected accent and habitually attempted to murder or wish death upon Wimpy; and Eugene the Jeep, a yellow, vaguely dog-like animal from Africa with magical powers. In addition, the strip featured the Sea Hag, a terrible pirate, as well as the last witch on earth (her even more terrible sister excepted); Alice the Goon, a monstrous creature who entered the strip as the Sea Hag's henchwoman and continued as Swee'Pea's babysitter; and Toar, a caveman.

Segar's strip was quite different from the cartoons that followed. The stories were more complex, with many characters that never appeared in the cartoons (King Blozo, for example). Spinach usage was rare and Bluto made only one appearance. Segar would sign some of his early Popeye comic strips with a cigar, due to his last name being a homophone of "cigar" (pronounced SEE-gar). The success of the strip meant Segar was earning $100,000 a year at the time of his death.[5]

Thimble Theatre became one of King Features' most popular strips during the 1930s. A poll of adult comic strip readers in the April 1937 issue of Fortune magazine voted Popeye their second favourite comic strip (after Little Orphan Annie).[5] By 1938, Thimble Theatre was running in 500 newspapers, and over 600 licensed "Popeye" products were on sale.[5] Following an eventual name change to Popeye in the 1970s, the comic remains one of the longest running strips in syndication today. After Mussolini came to power in Italy, he banned all American comic strips, but Popeye was so popular the Italians made him bring it back. The strip carried on after Segar's death in 1938, at which point he was replaced by a series of artists. In the 1950s, a spinoff strip was established, called Popeye the Sailorman.

Artists after Segar

After Segar's death in 1938, many different artists were hired to draw the strip. Tom Sims, the son of a Coosa River channel-boat captain, continued writing Thimble Theatre strips and established the Popeye the Sailorman spin-off. Doc Winner and Bela Zaboly,[10] successively, handled the artwork during Sims's run. Eventually, Ralph Stein stepped in to write the strip until the series was taken over by Bud Sagendorf in 1959.

Sagendorf wrote and drew the daily strip until 1986, and continued to write and draw the Sunday strip until his death in 1994. Sagendorf, who had been Segar's assistant, made a definite effort to retain much of Segar's classic style, although his art is instantly discernible. Sagendorf continued to use many obscure characters from the Segar years, especially O.G. Wotasnozzle and King Blozo. Sagendorf's new characters, such as the Thung, also had a very Segar-like quality. What set Sagendorf apart from Segar more than anything else was his sense of pacing. Where plotlines moved very quickly with Segar, it would sometimes take an entire week of Sagendorf's daily strips for the plot to be advanced even a small amount.

From 1986 to 1992, the daily strip was written and drawn by Bobby London, who, after some controversy, was fired from the strip for a story that could be taken to satirize abortion.[11] London's strips put Popeye and his friends in updated situations, but kept the spirit of Segar's original. One classic storyline, titled "The Return of Bluto", showed the sailor battling every version of the bearded bully from the comic strip, comic books, and animated films. The Sunday edition of the comic strip is currently drawn by Hy Eisman, who took over in 1994. The daily strip began featuring reruns of Sagendorf's strips after London was fired and continues to do so today.

On January 1, 2009, 70 years since the death of his creator, Segar's character of Popeye (though not the various films, TV shows, theme music and other media based on him) became public domain[12] in most countries, but remains under copyright in the United States. Because Segar was an employee of King Features Syndicate when he created the Popeye character for the company's Thimble Theatre strip, Popeye is treated as a work for hire under U.S. copyright law. Works for hire are protected for 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter. Since Popeye made his first appearance in January 1929, and all U.S. copyrights expire on December 31 of the year that the term ends, Popeye will enter the public domain in the U.S. on January 1, 2025, assuming no amendments to U.S. copyright law before that date.[13]

Reprints

- Popeye the Sailor, Nostalgia Press, 1971, reprints three daily stories from 1936.

- Thimble Theatre, Hyperion Press, 1977, ISBN 0-88355-663-4, reprints daily from September 10, 1928 missing 11 dailies which are included in the Fantagraphics reprints.

- Popeye, the First Fifty Years by Bud Sagendorf, Workman Publishing, 1979 ISBN 0-89480-066-3, the only Popeye reprint in full color.

- The Complete E. C. Segar Popeye, Fantagraphics, 1980s, reprints all Segar Sundays featuring Popeye in 4 volumes, all Segar dailies featuring Popeye in 7 volumes, missing 4 dailies which are included in the Hyperion reprint, November 20–22, 1928, August 22, 1929.

- Popeye. The 60th Anniversary Collection, Hawk Books Limited, 1989, ISBN 0-948248-86-6 featuring reprints a selection of strips and stories from the first newspaper strip in 1929 onwards, along with articles on Popeye in comics, books, collectables, etc.

- E. C. Segar's Popeye, between 2006 and 2011, Fantagraphics Books published six oversized hardcover volumes, reprinting all dailies and Sundays (in color, along with Sappo) featuring Popeye, plus various extras.

- Vol. 1: I Yam What I Yam – covers 1928–30 (November 22, 2006, ISBN 978-1-56097-779-7)

- Vol. 2: Well Blow Me Down! – covers 1930–32 (December 19, 2007, ISBN 978-1-56097-874-9)

- Vol. 3: Let's You and Him Fight! – covers 1932–33 (November 15, 2008, ISBN 978-1-56097-962-3)

- Vol. 4: Plunder Island – covers 1933–35 (December 22, 2009, ISBN 978-1-60699-169-5)

- Vol. 5: Wha's a Jeep – covers 1935–37 (March 21, 2011, ISBN 978-1-60699-404-7)

- Vol. 6: Me Li'l Swee'Pea – covers 1937–38 (November 15, 2011, ISBN 978-1-60699-483-2)

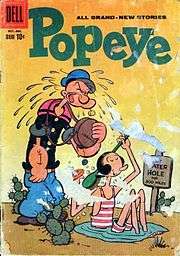

Comic books

There have been a number of Popeye comic books, from Dell, King Comics, Gold Key Comics, Charlton Comics and others, originally written and illustrated by Bud Sagendorf. In the Dell comics, Popeye became something of a crimefighter, thwarting evil organizations and Bluto's criminal activities. The new villains included the numerous Misermite dwarfs, who were all identical.

Popeye appeared in the British "TV Comic" series, a News of the World publication, becoming the cover story in 1960 with stories written and drawn by "Chick" Henderson. Bluto was referred to as Brutus and was Popeye's only nemesis throughout the entire run.

A variety of artists have created Popeye comic book stories since then; for example, George Wildman drew Popeye stories for Charlton Comics from 1969 until the late 1970s. The Gold Key series was illustrated by Wildman and scripted by Bill Pearson, with some issues written by Nick Cuti.

In 1988, Ocean Comics released the Popeye Special written by Ron Fortier with art by Ben Dunn. The story presented Popeye's origin story, including his given name of "Ugly Kidd"[14] and attempted to tell more of a lighthearted adventure story as opposed to using typical comic strip style humor. The story also featured a more realistic art style and was edited by Bill Pearson, who also lettered and inked the story as well as the front cover.[15] A second issue, by the same creative team, followed in 1988. The second issue introduced the idea that Bluto and Brutus were actually twin brothers and not the same person,[16] an idea also used in the comic strip on December 28, 2008 and April 5, 2009.[17][18] In 1999, to celebrate Popeye's 70th anniversary, Ocean Comics revisited the franchise with a one-shot comic book, entitled The Wedding of Popeye and Olive Oyl, written by Peter David. The comic book brought together a large portion of the casts of both the comic strip and the animated shorts, and Popeye and Olive Oyl were finally wed after decades of courtship. However, this marriage has not been reflected in all media since the comic was published.

In 1989, a special series of short Popeye comic books were included in specially marked boxes of Instant Quaker Oatmeal, and Popeye also appeared in three TV commercials for Quaker Oatmeal,[19] which featured a parrot delivering the tag line "Popeye wants a Quaker!" The plots were similar to those of the films: Popeye loses either Olive Oyl or Swee'Pea to a muscle-bound antagonist, eats something invigorating, and proceeds to save the day. In this case, however, the invigorating elixir was not his usual spinach, but rather one of four flavors of Quaker Oatmeal.[19] (A different flavor was showcased with each mini-comic.) The comics ended with the sailor saying, "I'm Popeye the Quaker Man!", which offended members of the Religious Society of Friends or Quakers.[20] Members of this religious group (which has no connection to the cereal company) are pacifists and do not believe in using violence to resolve conflicts. For Popeye to call himself a "Quaker man" after beating up someone was offensive to the Quakers and considered a misrepresentation of their faith and religious beliefs.[20] In addition, the submissiveness of Olive Oyl went against the Quakers' emphasis on women's rights. The Quaker Oatmeal company apologized and removed the "Popeye the Quaker man" reference from commercials and future comic book printings.[20]

In 2012, writer Roger Langridge teamed with cartoonists Bruce Ozella, Ken Wheaton, and Tom Neely (among others) to revive the spirit of Segar in IDW's 12-issue comic book miniseries, Popeye, Critic PS Hayes reviewed:

- Langridge writes a story with a lot of dialogue (compared to your average comic book) and it’s all necessary, funny, and entertaining. Bruce Ozella draws the perfect Popeye. Not only Popeye, but Popeye’s whole world. Everything looks like it should, cartoony and goofy. Plus, he brings an unusual amount of detail to something that doesn’t really need it. You’ll swear that you’re looking at an old Whitman Comics issue of Popeye, only it’s better. Ozella is a great storyteller and even though the issue is jam packed with dialog, the panels never look cramped at all.[21]

In late 2012, IDW began reprinting the original 1940s–1950s Sagendorf Popeye comic books under the title of Classic Popeye.

Theatrical animated cartoons

In November 1932, King Features signed an agreement with Fleischer Studios to have Popeye and the other Thimble Theatre characters begin appearing in a series of animated cartoons. The first cartoon in the series was released in 1933, and Popeye cartoons, released by Paramount Pictures, would remain a staple of Paramount's release schedule for nearly 25 years. William Costello was the original voice of Popeye, a voice that would be replicated by later performers, such as Jack Mercer and even Mae Questel. Many of the Thimble Theatre characters, including Wimpy, Poopdeck Pappy, and Eugene the Jeep, eventually made appearances in the Paramount cartoons, though appearances by Olive Oyl's extended family and Ham Gravy were notably absent. Thanks to the animated-short series, Popeye became even more of a sensation than he had been in comic strips, and by 1938, polls showed that the sailor was Hollywood's most popular cartoon character.[22][23]

In every Popeye cartoon, the sailor is invariably put into what seems like a hopeless situation, upon which (usually after a beating), a can of spinach which he apparently regularly carries with him falls out from inside his shirt. Popeye immediately pops the can open and gulps the entire contents of it into his mouth, or sometimes sucks in the spinach through his corncob pipe. Upon swallowing the spinach, Popeye's physical strength immediately becomes superhuman, and he is easily able to save the day (and very often rescue Olive Oyl from a dire situation). It did not stop there, as spinach could also give Popeye the skills and powers he needed, as in The Man on the Flying Trapeze, where it gave him acrobatic skills. (When the antagonist is the Sea Hag, it is Olive who eats the spinach; Popeye can't hit a lady.)

In May 1941, Paramount Pictures assumed ownership of Fleischer Studios, fired the Fleischers and began reorganizing the studio, which they renamed Famous Studios. The early Famous-era shorts were often World War II-themed, featuring Popeye fighting Nazis and Japanese soldiers, most notably the 1942 short You're a Sap, Mr. Jap. In late 1943, the Popeye series was moved to Technicolor production, beginning with Her Honor the Mare. Famous/Paramount continued producing the Popeye series until 1957, with Spooky Swabs being the last of the 125 Famous shorts in the series. Paramount then sold the Popeye film catalog to Associated Artists Productions, which was bought out by United Artists in 1958 and merged with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer 23 years later, which was itself purchased by Turner Entertainment in 1986. Then Turner sold off the production end of MGM/UA shortly after, but retained the film catalog, giving it the rights to the theatrical Popeye library. The black-and-white Popeye shorts were shipped to South Korea in 1985, where artists retraced them into color. The retraced shorts were syndicated in 1987 on a barter basis, and remained available until the early 1990s. Turner merged with Time Warner in 1996, and Warner Bros. (through its Turner subsidiary) therefore currently controls the rights to the Popeye shorts.

In 2001, the Cartoon Network, under the supervision of animation historian Jerry Beck, created a new incarnation of The Popeye Show. The show aired the Fleischer and Famous Studios Popeye shorts in versions approximating their original theatrical releases by editing copies of the original opening and closing credits (taken or recreated from various sources) onto the beginnings and ends of each cartoon, or in some cases, in their complete, uncut original theatrical versions direct from such prints that originally contained the front-and-end Paramount credits. The series aired 135 Popeye shorts over forty-five episodes, until March 2004. The Popeye Show continued to air on Cartoon Network's spin-off network Boomerang.

While many of the Paramount Popeye cartoons remained unavailable on video, a handful of those cartoons had fallen into public domain and were found on numerous low budget VHS tapes and later DVDs. When Turner Entertainment acquired the cartoons in 1986, a long and laborious legal struggle with King Features kept the majority of the original Popeye shorts from official video releases for more than 20 years. King Features instead opted to release a DVD boxed set of the 1960s made-for-television Popeye the Sailor cartoons, to which it retained the rights, in 2004. In the meantime, home video rights to the Associated Artists Productions library were transferred from CBS/Fox Video to MGM/UA Home Video in 1986, and eventually to Warner Home Video in 1999. In 2006, Warner Home Video announced it would release all of the Popeye cartoons produced for theatrical release between 1933 and 1957 on DVD, restored and uncut. Three volumes were released between 2007 and 2008, covering all of the Fleischer era and the beginnings of the Famous era.

Original television cartoons

In 1960, King Features Syndicate commissioned a new series of cartoons entitled Popeye the Sailor, but this time for television syndication. Al Brodax served as executive producer of the cartoons for King Features. Jack Mercer, Mae Questel, and Jackson Beck returned for this series, which was produced by a number of companies, including Jack Kinney Productions, Rembrandt Films (William L. Snyder and Gene Deitch), Larry Harmon Productions, Halas and Batchelor, Paramount Cartoon Studios (formerly Famous Studios), and Southern Star Entertainment (formerly Southern Star Productions). The artwork was streamlined and simplified for the television budgets, and 220 cartoons were produced in only two years, with the first set of them premiering in the autumn of 1960, and the last of them debuting during the 1961–1962 television season. Since King Features had exclusive rights to these Popeye cartoons, 85 of them were released on DVD as a 75th anniversary Popeye boxed set in 2004.

For these cartoons, Bluto's name was changed to "Brutus", as King Features believed at the time that Paramount owned the rights to the name "Bluto". Many of the cartoons made by Paramount used plots and storylines taken directly from the comic strip sequences – as well as characters like King Blozo and the Sea Hag.[24] The 1960s cartoons have been issued on both VHS and DVD.

On September 9, 1978, The All New Popeye Hour debuted on the CBS Saturday morning lineup. It was an hour-long animated series produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions, which tried its best to retain the style of the original comic strip (Popeye returned to his original costume and Brutus to his original name of Bluto), while complying with the prevailing content restrictions on violence. In addition to providing many of the cartoon scripts, Mercer continued to voice Popeye, while Marilyn Schreffler and Allan Melvin became the new voices of Olive Oyl and Bluto, respectively. (Mae Questel actually auditioned for Hanna-Barbera to recreate Olive Oyl, but was rejected in favor of Schreffler.) The All New Popeye Hour ran on CBS until September 1981, when it was cut to a half-hour and retitled The Popeye and Olive Show. It was removed from the CBS lineup in September 1983, the year before Jack Mercer's death. These cartoons have also been released on VHS and DVD. During the time these cartoons were in production, CBS aired The Popeye Valentine's Day Special – Sweethearts at Sea on February 14, 1979. In the UK, the BBC aired a half-hour version of The All New Popeye Show, from the early-1980s to 2004.

Popeye briefly returned to CBS in 1987 for Popeye and Son, another Hanna-Barbera series, which featured Popeye and Olive as a married couple with a son named Popeye Jr., who hates the taste of spinach but eats it to boost his strength. Maurice LaMarche performed Popeye's voice; Mercer had died in 1984. The show lasted for one season.

In 2004, Lions Gate Entertainment produced a computer-animated television special, Popeye's Voyage: The Quest for Pappy, which was made to coincide with the 75th anniversary of Popeye. Billy West performed the voice of Popeye, describing the production as "the hardest job I ever did, ever" and the voice of Popeye as "like a buzzsaw on your throat".[25] The uncut version was released on DVD on November 9, 2004; and was aired in a re-edited version on Fox on December 17, 2004 and again on December 30, 2005. Its style was influenced by the 1930s Fleischer cartoons, and featured Swee'Pea, Wimpy, Bluto (who is Popeye's friend in this version), Olive Oyl, Poopdeck Pappy and the Sea Hag as its characters. On November 6, 2007, Lions Gate Entertainment re-released Popeye's Voyage on DVD with redesigned cover art.

Popeye has made brief parody appearances in modern animated productions, including:

- A typical Popeye style rescue was spoofed in The Simpsons episode "Jaws Wired Shut".

- In The Critic, Jay Sherman's father Franklin flashes back to saving his wife Popeye style with alcohol instead of spinach.

- Popeye appeared in the Drawn Together episode "The Lemon-AIDS Walk", voiced by Billy West.

- In the Family Guy episode "You May Now Kiss the...Uh...Guy Who Receives", Popeye's unique behavior and speech patterns are explained as being the result of a stroke, and his massive forearm muscles are actually cancerous tumors.

- Popeye co-stars in a short from Seth MacFarlane's Cavalcade of Cartoon Comedy giving Bob Dylan a hard time about him not singing his hit song, "Blowin' in the Wind".

- Popeye appeared in the Robot Chicken episodes "The Sack", "Squaw Bury Shortcake" and "Yancy the Yo-Yo Boy", voiced by Dave Coulier (which he was known to perform often during his co-starring role on the ABC sitcom Full House).

- Popeye appeared in the South Park "Imaginationland" three-parter as one of the members of the Council of Nine. Popeye's appearance in one scene evoked that of the character Karl in the movie Sling Blade, as Popeye sharpened a blade, much as Karl sharpened a lawnmower blade near the end of Sling Blade.

Theme song

Popeye’s theme song, titled "I'm Popeye The Sailor Man", composed by Sammy Lerner in 1933 for Fleischer’s first Popeye the Sailor cartoon,[26] has become forever associated with the sailor. "The Sailor's Hornpipe" has often been used as an introduction to Popeye's theme song.

A cover of the theme song, performed by Face to Face, is included on the 1995 tribute album Saturday Morning: Cartoons' Greatest Hits, produced by Ralph Sall for MCA Records. A jazz version, performed by Ted Kooshian's Standard Orbit Quartet, appears on their 2009 Summit Records release Underdog and Other Stories.

Playground song parodies of the theme have become part of children's street culture around the world,[27][28] usually interpolating "frying pan" or "garbage can" into the lyrics as Popeye's dwelling place[29][30] and ascribing to the character various unsavory actions or habits[31][32][33][34] that transform the character into an "Anti-Popeye", and changing his exemplary spinach-based diet into an inedible morass of worms, onions, flies, tortillas and snot.[35]

Other media

The success of Popeye as a comic-strip and animated character has led to appearances in many other forms. For more than 20 years, Stephen DeStefano has been the artist drawing Popeye for King Features licensing.[36]

Radio

Popeye was adapted to radio in several series broadcast over three different networks by two sponsors from 1935 to 1938. Popeye and most of the major supporting characters were first featured in a thrice-weekly 15-minute radio program, Popeye the Sailor, which starred Detmar Poppen as Popeye along with most of the major supporting characters—Olive Oyl (Olive Lamoy), Wimpy (Charles Lawrence), Bluto (Jackson Beck) and Swee'Pea (Mae Questel). In the first episode, Popeye adopted Sonny (Jimmy Donnelly), a character later known as Matey the Newsboy. This program was broadcast Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday nights at 7:15pm. September 10, 1935 through March 28, 1936 on the NBC Red Network (87 episodes), initially sponsored by Wheatena, a whole-wheat breakfast cereal, which would routinely replace the spinach references. Music was provided by Victor Irwin's Cartoonland Band. Announcer Kelvin Keech sang (to composer Lerner's "Popeye" theme) "Wheatena is his diet / He asks you to try it / With Popeye the sailor man." Wheatena paid King Features Syndicate $1,200 per week.

The show was next broadcast Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays from 7:15 to 7:30pm on WABC and ran from August 31, 1936 to February 26, 1937 (78 episodes). Floyd Buckley played Popeye, and Miriam Wolfe portrayed both Olive Oyl and the Sea Hag. Once again, reference to spinach was conspicuously absent. Instead, Popeye sang, "Wheatena's me diet / I ax ya to try it / I'm Popeye the Sailor Man".[37]

The third series was sponsored by the maker of Popsicle three nights a week for 15 minutes at 6:15 pm on CBS from May 2, 1938 through July 29, 1938.

Of the three series, only 20 of the 204 episodes are known to be preserved.

Films

Popeye (1980)

Director Robert Altman used the character in Popeye, a 1980 live-action musical feature film, starring Robin Williams as Popeye (his first movie role), Shelley Duvall as Olive Oyl, and Paul L. Smith as Bluto, with songs by Harry Nilsson and Van Dyke Parks. The script was by Jules Feiffer, who adapted the 1971 Nostalgia Press book of 1936 strips for his screenplay, thus retaining many of the characters created by Segar. A co-production of Paramount Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, the movie was filmed almost entirely on Malta, in the village of Mellieħa on the northwest coast of the island. The set is now a tourist attraction called Popeye Village. The US box office earnings were double the film's budget, making it a success.

Upcoming film

In March 2010, it was reported that Sony Pictures Animation is developing a 3-D computer-animated Popeye film, with Avi Arad producing it.[38] In November 2011, Sony Pictures Animation announced that Jay Scherick and David Ronn, the writers of The Smurfs, are writing the screenplay for the film.[39] In June 2012, it was reported that Genndy Tartakovsky had been set to direct the feature,[40] which he planned to make "as artful and unrealistic as possible."[41] In November 2012, Sony Pictures Animation set the release date for September 26, 2014,[42] which was, in May 2013, pushed back to 2015.[43] In March 2014, Sony Pictures Animation updated its slate, scheduling the film for 2016, and announcing Tartakovsky as the director of Hotel Transylvania 2, which he was directing concurrently with Popeye.[44] On September 18, 2014, Tartakovsky revealed an "animation test" footage, about which he said, "It's just something that kind of represents what we want to do. I couldn't be more excited by how it turned out."[45] In March 2015, Tartakovsky announced that despite the well-received test footage, he was no longer working on the project, and would instead direct Can You Imagine?, which is based on his own original idea.[46] Nevertheless, Sony Pictures Animation stated the project still remains in active development.[47] In January 2016, it was announced that T. J. Fixman would write the film.[48]

Video and pinball games

- Nintendo created a widescreen Game & Watch called Popeye in 1981. The handheld game featured Popeye on a boat, and the aim was to catch bottles, pineapples, and spinach cans thrown by Olive Oyl while trying to avoid Bluto's boat. If Bluto hit Popeye on the head with his mallet or Popeye failed to catch an object three times, the game would end.

- The Nintendo arcade game Donkey Kong was originally conceived as a Popeye video game by Shigeru Miyamoto. But due to licensing disagreements with King Features, this idea was scrapped.[49]

- When Donkey Kong went on to enormous success, King Features agreed to license the characters to Nintendo to create a Popeye arcade game in 1982. It was later ported to the Commodore 64 home computer as well as various home game consoles: Intellivision, Atari 2600, ColecoVision, Famicom/NES, and Odyssey2. The goal was to avoid Bluto (referred to as "Brutus") and the Sea Hag while collecting items produced by Olive Oyl such as hearts, musical notes, or the letters in the word "help" (depending on the level). Hitting a can of spinach gave Popeye a brief chance to strike back at Brutus. Other characters such as Wimpy and Swee' Pea appeared in the game but did not greatly affect gameplay. A board game based on the video game was released by Parker Brothers.

- A table top Game & Watch style game was also released by Nintendo in 1983, which featured Popeye trying to rescue Olive while engaging in fisticuffs with Bluto.

- Nintendo created another Popeye game for the Famicom, Popeye no Eigo Asobi, in 1983. This was an educational game designed to teach Japanese children English words.

- Two Popeye games published by Sigma Enterprises were spawned for the Game Boy. The first Game Boy Popeye game, which was released exclusively in Japan in 1990, and Popeye 2 in 1991. Popeye 2 was also released in North America (1993) and Europe (1994) by Activision.

- In 1994, Technos Japan released Popeye: Beach Volleyball for the Game Gear, and Popeye: Volume of the Malicious Witch Seahag (Popeye: Ijiwaru Majo Shihaggu no Maki) for the Japanese Super Famicom. A side scrolling adventure game that was mixed with a board game, the game never saw US release, but a ROM of the game can be found at various emulation sites. It featured many characters from the Thimble Theatre series as well. In the game, Popeye had to recover magical hearts scattered across the level to restore his frozen friends as part of a spell cast upon them by the Sea Hag in order to get revenge on Popeye.

- Midway (under the Bally label) released Popeye Saves the Earth, a SuperPin pinball game, in 1994.

- In 2003, Nova Productions released a strength tester called Popeye Strength Tester.

- In 2005, Namco released a Game Boy Advance video game called Popeye: Rush for Spinach.

- Released June 2007, the video game The Darkness featured televisions that played full-length films and television shows that had expired copyrights. Most of the cartoons viewable on the "Toon TV" channel are Famous Studios Popeye shorts.

- In fall 2007, Namco Networks released the original Nintendo Popeye arcade game for mobile phones with new features including enhanced graphics and new levels.

Marketing, tie-ins, and endorsements

From early on, Popeye was heavily merchandised. Everything from soap to razor blades to spinach was available with Popeye's likeness on it. Most of these items are rare and sought-after by collectors, but some merchandise is still being produced.

- Games and toys

- Mezco Toyz makes classic-style Popeye figures in two sizes.

- KellyToys produces plush stuffed Popeye characters.

- Restaurants

- Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen (aka Popeyes Chicken & Biscuits), a fast food restaurant chain, is not named after Popeye the Sailor but after the character "Popeye" Doyle from the 1971 film The French Connection, who was in turn named after real police detective Eddie Egan, who was called "Pop Eye" because of his keen observational skills. The restaurant chain would later obtain a license for use of the cartoon character and advertise the name as Popeye's after Popeye the Sailor, causing some confusion as to the source of the name. Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen locations in Puerto Rico make extensive use of Popeye the Sailor and associated characters.[50]

- Wimpy's name was borrowed for the Wimpy restaurant chain, one of the first international fast food restaurants featuring hamburgers, which they call "Wimpy Burgers".[51]

- Retail foods and beverages

- Allen Canning Company produces its own line of spinach, called "Popeye Spinach", in various canned varieties. The cartoon Popeye serves as the mascot on the can.[52]

- In 1961, Buitoni Pasta marketed Popeye-shaped spinach macaroni.

- Popeye appeared in a 1979 Dr Pepper commercial during the "Be a Pepper" campaign (possibly as a tie-in for the movie, going so far as to modify his traditional catchphrase to "I'm Popeye the Pepper-man").

- Since 1989, "Popeye's Supplements" has been a chain of Canadian Sports Nutrition Stores.[53]

- In 1989, Popeye endorsed Instant Quaker Oatmeal, citing it as a better food than spinach to provide strength.[19] The commercials had the tagline "Can the spinach, I wants me Quaker Oatmeal!" The Religious Society of Friends (also known as the Quakers) was offended by the promotion given the physical aggression from "Popeye the Quaker man" and also the excessive submissiveness of Olive Oyl.[20]

- In 2001, Popeye (along with Bluto, Olive, and twin Wimpys) appeared in a television commercial for Minute Maid Orange juice. The commercial, produced by Leo Burnett Co, showed Popeye and Bluto as friends (and neglecting Olive Oyl) due to their having had Minute Maid Orange Juice that morning. The ad agency's intention was to show that even the notable enemies would be in a good mood after their juice, but some, including Robert Knight of the Culture and Family Institute, felt the commercial's intent was to portray the pair in a homosexual romantic relationship—while there is nothing wrong with that, it is a suggestion that Minute Maid denies. Knight was interviewed by Stephen Colbert on Comedy Central's The Daily Show about this issue.

- World Candies Inc. produced Popeye-branded "candy cigarettes", which were small sugar sticks with red dye at the end to simulate a flame. They were sold in a small box, similar to a cigarette pack. The company still produces the item, but has since changed the name to "Popeye Candy Sticks" and has ceased putting the red dye at the end.

- In 2013, McLean Design produced a packaging design using licensed characters and artwork for a Popeye branded energy drink. The drink is launching in the US with two flavors.[54]

- Sports

- Starting in 1940, Popeye became the mascot of Flamengo (Rio de Janeiro – Brazil), the most popular soccer team with almost 50 million fans around the world. The mascot of the soccer club is currently a cartoon vulture.[55]

- Other

- In 1979, salsa singer Adalberto Santiago releases Adalberto Santiago Featuring Popeye El Marino. Fania Records JM 536.

- During the 1960s, Popeye appeared in advertising for Crown gasoline.

- In 1987, Stabur Graphics commissioned artist Will Elder to paint "Popeye's Wedding" as oil on masonite. Released was a stamped, numbered and signed Limited Edition lithograph, edition size of 395. The lithograph shows Popeye and Olive Oyl in front of the preacher (Popeye slipping a lifesaver-ring onto Olive's finger) along with Nana Oyl, Alice the Goon, Swee'Pea (cradled in Popeye's free arm), Wimpy, Granny, Eugene the Jeep and Brutus (holding a large cauldron of steaming, cooked rice). Twenty-one other characters watch from the pews. The litho is titled "Wit Dis Lifesaver, I Dee Wed!" and is pictured on page 83 of the book "Chicken Fat" by Will Elder (Fantagraphics, 2006).

- In 1990, Popeye appeared in an advertisement warning of the harmful effects of coastal pollution. Bluto is laughing as he carelessly dumps garbage over the side of his boat, to which Olive reacts in horror as seagulls and other sea creatures are caught in six pack ring holders. Popeye punches out Bluto and cleans up his garbage; however, when some more plastic garbage sails by Popeye's boat, he says unsurprisingly, "I can't do it all meself, you know!"

- In 1995, the Popeye comic strip was one of 20 included in the Comic Strip Classics series of commemorative U.S. postage stamps.

- From 1996 to 1999, the Darien Lake theme park in Western New York operated a "Popeye's Seaport" in the park. It was rebranded as "Looney Tunes Seaport" after Darien Lake came under the Six Flags banner.

- In the 1997 film Alien: Resurrection, Don Vriess (Dominique Pinion) whistles the Popeye theme song.

- In 2006, King Features Syndicate produced a radio spot and an industrial for the United States Power Squadrons featuring Robyn Gryphe as Olive and Allen Enlow as Popeye.

- In October 2007, to coincide with the launch of the Popeye mobile game, Namco Networks and Sprint launched a Popeye the Sailorman sweepstakes offering the authorized edition four-disc Popeye the Sailor: 1933–1938 Vol. 1 DVD set as grand prize.[56]

- In Islands of Adventure, there is a river rafting water ride, Popeye and Bluto's Bilge-Rat Barges, themed after Popeye the Sailor saving Olive Oyl from Bluto.

Cultural origins and impact

Local folklore in Chester, Illinois, Segar's hometown, claims that Popeye is based on Frank "Rocky" Fiegel, a man who was handy with his fists.[57] Fiegel was born on January 27, 1868. He lived as a bachelor his entire life. According to local Popeye historian Michael Brooks, Segar regularly sent money to Fiegel.[58]

Culturally,[59] many consider Popeye a precursor to the superheroes who would eventually come to dominate US comic books.[60]

Such has been Popeye's cultural impact that the medical profession sometimes refers to the biceps bulge symptomatic of a tendon rupture as the "Popeye muscle."[61][62] Note, however, that under normal (non-spinach-influenced) conditions, Popeye has pronounced muscles of the forearm, not of the biceps.

In 1973, Cary Bates created Captain Strong, a takeoff of Popeye, for DC Comics,[63] as a way of having two cultural icons – Superman and (a proxy of) Popeye – meet.[64]

The 1988 Disney/Touchstone film Who Framed Roger Rabbit featured many classic cartoon characters, and the absence of Popeye was noted by some critics. Popeye (along with Bluto and Olive Oyl) actually had a role planned for the film. However, since the Popeye cartoons were based on a comic strip, Disney found they had to pay licensing fees to both King Features Syndicate and MGM/UA. MGM/UA's pre-May 1986 library (which included Popeye) was being purchased by Turner Entertainment at the time, which created legal complications; thus, the rights could not be obtained and Popeye's cameo was dropped from the film.[65]

The Popeye Dance

The Popeye was a popular dance in the dance craze era of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Originating in New Orleans around 1962, the Popeye was performed by shuffling and moving one's arms, placing one arm behind and one arm in front and alternating them, going through the motion of raising a pipe up to the mouth, and alternate sliding or pushing one foot back in the manner of ice skating, similar to motions exhibited by the cartoon character. According to music historian Robert Pruter, the Popeye was even more popular than The Twist in New Orleans.[66] The dance was associated with and/or referenced to in several songs, including Eddie Bo's "Check Mr. Popeye," Chris Kenner's "Something You Got" and "Land of a Thousand Dances," Frankie Ford's "You Talk Too Much," Ernie K-Doe's "Popeye Joe," Huey "Piano" Smith's "Popeye," and Harvey Fuqua's "Any Way You Wanta." A compilation of 23 Popeye dance songs was released in 1996 under the title "New Orleans Popeye Party." [67]

Spinach

Initially Popeye's chief superhuman characteristic was his indestructibility, rather than super strength, which was attributed to his having rubbed the head of Bernice the Whiffle Hen numerous times after being shot. Popeye later attributed his strength to spinach.[68][69] The popularity of Popeye helped boost spinach sales. Using Popeye as a role model for healthier eating may work; a 2010 study revealed that children increased their vegetable consumption after watching Popeye cartoons.[70] The spinach-growing community of Crystal City, Texas, erected a statue of the character in recognition of Popeye's positive effects on the spinach industry. There is another Popeye statue in Segar's hometown, Chester, Illinois, and statues in Springdale and Alma, Arkansas (which claims to be "The Spinach Capital of the World"), at canning plants of Allen Canning, which markets Popeye-branded canned spinach. In addition to Allen Canning's Popeye spinach, Popeye Fresh Foods markets bagged, fresh spinach with Popeye characters on the package. In 2006, when spinach contaminated with E. coli was accidentally sold to the public, many editorial cartoonists lampooned the affair by featuring Popeye in their cartoons.[71]

A frequently circulated story claims that Fleischer's choice of spinach to give Popeye strength was based on faulty calculations of its iron content. In the story, a scientist misplaced a decimal point in an 1870 measurement of spinach's iron content, leading to an iron value ten times higher than it should have been. This faulty measurement was not noticed until the 1930s.[72][73][74] While this story has gone through longstanding circulation, recent study has shown that this is a myth,[75][76] and it was chosen for its vitamin A content alone;[77] see Spinach: Popeye and iron.

Word coinages

The strip is also responsible for popularizing, although not inventing, the word "goon" (meaning a thug or lackey); goons in Popeye's world were large humanoids with indistinctly drawn faces that were particularly known for being used as muscle and slave labor by Popeye's nemesis, the Sea Hag. One particular goon, the aforementioned female named Alice, was an occasional recurring character in the animated shorts, but she was usually a fairly nice character.

Eugene the Jeep was introduced in the comic strip on March 13, 1936. Two years later the term "jeep wagons" was in use, later shortened to simply "jeep" with widespread World War II usage and then trademarked by Willys-Overland as "Jeep".[78]

Events and honors

The Popeye Picnic is held every year in Chester, Illinois on the weekend after Labor Day. Popeye fans attend from across the globe, including a visit by a film crew from South Korea in 2004. The one-eyed sailor's hometown strives to entertain devotees of all ages.[79]

In honor of Popeye’s 75th anniversary, the Empire State Building illuminated its notable tower lights green the weekend of January 16–18, 2004 as a tribute to the icon’s love of spinach. This special lighting marked the only time the Empire State Building ever celebrated the anniversary/birthday of a comic strip character.[80]

Thimble Theatre/Popeye characters

Characters originating in the comic strips

- Popeye the Sailor Man

- Olive Oyl

- Ham Gravy (full name Harold Hamgravy, Olive Oyl's original boyfriend)

- Castor Oyl (Olive Oyl's brother)

- Cole Oyl (Olive Oyl's father)

- Nana Oyl (Olive Oyl's mother)

- Bernice (The "Whiffle Bird" in 1960s King Features TV shorts)

- Sutra oyl (olive's cousin)

- Motor oyl(sutra oyl's punk husband)

- The Sea Hag

- Salty the parott

- Ghost island's ghost

- the doomsday doll

- The Sea Hag's vultures, specifically Bernard

- J. Wellington Wimpy

- George W. Geezil (the local cobbler who hates Wimpy)

- Rough House (a cook who runs a local restaurant, The Rough House)

- Swee'Pea (Popeye's adopted baby son in the comics, Olive's cousin in the cartoons)

- King Blozo

- Misermites (A race of thieving dwarves)

- Toar (a 900-pound caveman living in the modern age)

- Bluto/Brutus

- Goons, specifically Alice the Goon

- Poopdeck Pappy (Popeye's 99-year-old long-lost father; also a sailor)

- Eugene the Jeep

- Saddarn Shahame (dictator of Bananastan)

- Barnacle (salty) Bill (a fellow sailor and old friend)

- Oscar

- Pooky Jones (dwarf and poopdeck pappy's best friend/partner in crime)

- Horace (Native American guide and friend of popeye)

- Bolo (Humanoid slave of the sea hag)

- general Bunzo

- Patcheye the pirate (popeye's anscestor)

- Oscar wimpy (A.K.A. the nicest man on earth)

- sir Pomeroy (eplorator and later archeologist friend of popeye)

- Liverstone (popeye's pet seagull)

- Mary ann (popeye's adopted daughter for a few strips)

- Jhonny Doodle (pilot friend of olive)

- Bill Squid (rival of popeye)

- Bullo Oxheart and his mother (boxer rival of popeye)

- Davy Jones

- Snagg and Baby Doll (spinachovian criminals)

- Battling McGnat (popeye's boxing manager)

- B. Loony Bullony (depressive cartoonist)

- Georges the giant

- Dufus (the son of a family friend)

- Mars men (coming in various forms)

- Mr. Sloppy (Co-owner of the rough house cafe)

- SweetHaven short supremascist

- Granny (Popeye's grandmother and Poopdeck's mother)

- Professor O. G. Watasnozzle[81][82] (a character with a large nose, as his name indicates)

- Otis O. Otis, "The world's smartest detective"[83] as well as Wimpy's cousin filmmaker Otis Von Lens Cover[84][85]

Characters originating in the cartoons

- Pipeye, Pupeye, Poopeye, Peepeye (Popeye's identical nephews)

- Shorty (Popeye's shipmate in three World War II-era Famous Studios shorts)

- Diesel Oyl (Olive's identical niece, a conceited brat who appears in three of the 1960s King Features shorts)

- Popeye, Jr. (son of Popeye and Olive Oyl, exclusive of the series Popeye and Son)

- Tank (son of Brutus, exclusive of the series Popeye and Son)

Filmography

Theatrical

- Popeye the Sailor (produced by Fleischer Studios) (1933–1942, 108 cartoons)

- Popeye the Sailor (produced by Famous Studios) (1942–1957, 122 cartoons)

Television

- Popeye the Sailor (1960–1962; produced by Jack Kinney Productions, Rembrandt Films (animated by Gene Deitch), Halas and Batchelor, Larry Harmon Pictures, TV Spots, and Paramount Cartoon Studios for King Features Syndicate, 220 cartoons)

- The All New Popeye Hour, later The Popeye and Olive Comedy Show (1978–1983, CBS; produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions, 159 cartoons)

- Popeye and Son (1987–1988, CBS; produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions, 26 cartoons)

- The Popeye Show (2001–2003, Cartoon Network, repeats)

Television specials

- Popeye Meets the Man Who Hated Laughter (1972)

- The Popeye Valentine's Day Special: Sweethearts at Sea (1979, produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions)

- Popeye's Voyage: The Quest for Pappy (2004 telefilm, produced by Mainframe Entertainment for Lions Gate Entertainment and King Features)

Live-action Feature Films

- Popeye (1980 live-action film, produced by Paramount Pictures and Walt Disney Productions, directed by Robert Altman)

DVD collections

- Popeye the Sailor: 1933–1938, Volume 1 (released July 31, 2007) features Fleischer cartoons released from 1933 through early 1938 and contains the color Popeye specials Popeye the Sailor Meets Sindbad the Sailor and Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba's Forty Thieves.

- Popeye the Sailor: 1938–1940, Volume 2 (released June 17, 2008) features Fleischer cartoons released from mid-1938 through 1940 and includes the last color Popeye special Aladdin and His Wonderful Lamp.

- Popeye the Sailor: 1941–1943, Volume 3 (released November 4, 2008) features the remaining black-and-white Popeye cartoons released from 1941 to 1943, including the final Fleischer-produced and earliest Famous-produced entries in the series.

- Popeye – 75th Anniversary Collector's edition (released April 27, 2004) features 85 cartoons from the Popeye the Sailor 1960s series.

- Popeye and Friends: Volume 1 (released June 17, 2008) features a collection of eight cartoons from The All New Popeye Hour. A second volume containing cartoons from Popeye and Son was scheduled, but it was cancelled before being released (it was subsequently released in the UK and Australia).

References

- ↑ Scott, Keith. "Popeye's Bilge-Rat Barges".

- ↑ "Popeye (2016)". behindthevoiceactors.com.

- ↑ Segar, Elzie (Crisler) – Encyclopædia Britannica Article. Britannica.com. Retrieved on March 29, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Goulart, Ron, "Popeye", St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Detroit : St. James Press, 2000. (Volume 4, pp. 87-8).ISBN 9781558624047

- 1 2 3 4 Walker, Brian. The Comics : The Complete Collection. New York : Abrams ComicArts, 2011. (pp. 188-9,191, 238-243) ISBN 9780810995956

- ↑ ""Popeye comes to DVD from Warner Home Video"".

- ↑ Mendelson, Lee and Schulz,Charles M., Charlie Brown and Charlie Schulz : in celebration of the 20th anniversary of "Peanuts". New York : New American Library, 1971. (p. 35)

- ↑ TV Guide Book of Lists. Running Press. 2007. p. 158. ISBN 0-7624-3007-9.

- ↑ "13 Interesting Popeye the Sailorman Facts". todayifoundout.com. December 3, 2012.

- ↑ Lambiek comic shop and studio in Amsterdam, The Netherlands (June 16, 2007). "Comic creator: Bill Zaboly". Lambiek.net. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ Bobby London Interview. comic-art.com. Retrieved on March 29, 2013.

- ↑ CBC News, "Popeye, Grey Owl and Robert Service join the public domain," January 12, 2009. Cbc.ca (January 12, 2009). Retrieved on March 29, 2013.

- ↑ Quinn, Gene (January 5, 2009). "Popeye Falls into Public Domain in Europe". IPWatchdog.com. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ↑ Sterling, Mike (September 20, 2012). "I Sorta Do and Sorta Don't Want This to Be Officially Part of Popeye's Backstory". Progressive Ruin. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- ↑ Fortier, Ron (w), Dunn, (p), Pearson, Bill (i). "Borned to the Sea" Popeye Special 1 (June 1987), Ocean Comics

- ↑ Fortier, Ron (w), Dunn, Ben, Grummett, Tom, Kato, Gary (p), Barras, Dell (i). "Double Trouble Down Under" Popeye Special 2 (September 1988), Ocean Comics

- ↑ December 28, 2008 Popeye Cartoon; retrieved July 14, 2009.

- ↑ April 5, 2009 Popeye Cartoon; retrieved July 14, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Popeye snubs his spinach for oatmeal". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (retrieved via Google News). 1990-03-28. p. 22. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Stieg, Bill (1990-04-24). "Popeye's pugnacity steams up Quakers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (retrieved via Google News). p. 6. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ↑ "Review: Popeye #1", Geeks of Doom, April 25, 2012. Geeksofdoom.com (April 25, 2012). Retrieved on March 29, 2013.

- ↑ "GAC Forums – Popeye's Popularity – Article from 1935". Forums.goldenagecartoons.com. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Popeye From Strip To Screen". Awn.com. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ Ian. "The S Dope Mailbag: Is Popeye's nemesis named Bluto or Brutus?". Straightdope.com. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ Penn's Sunday School (August 9, 2012). "The many voices of Billy West" – via YouTube.

- ↑ CD liner notes: Saturday Morning: Cartoons' Greatest Hits, 1995 MCA Records

- ↑ "Popeye the Sailor Man".

- ↑ "Folklore from Contemporary Jamaicans".

- ↑ "popeye the sailor man".

- ↑ "Im Popeye the Sailor Man".

- ↑ "Yo Mama!: New Raps, Toasts, Dozens, Jokes, and Children's Rhymes from Urban Black America".

- ↑ "The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren".

...for some reason he chiefly features in verses which are obscene.

- ↑ "American Children's Folklore".

- ↑ "From Abba to Zoom: A Pop Culture Encyclopedia of the Late 20th Century".

- ↑ "Children's Folklore: A SourceBook".

Each parody creates a fictive world that stands as a miniature rite of rebellion, a vision of a counter-factual world inhabited by worm-eating garbage-can residents, and tortilla-wielding aunt-killers. The exemplary Popeye is converted into an anti-Popeye, exhibiting filthy and murderous qualities obviously anathema to the conventional etiquette.

- ↑ "A Clean Shaven Man", July 2010. Fullecirclestuff.blogspot.com. Retrieved on March 29, 2013.

- ↑ 1930s Popeye the Sailor Wheatena audio clip.

- ↑ "Sony making a CG Popeye Film". comingsoon.net. March 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Sony Pictures Animation and Arad Productions Set Jay Scherick & David Ronn to Write Animated POPEYE". Sony Pictures Animation via PR Newswire. November 3, 2011. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ Abrams, Rachel (June 25, 2012). "Helmer moves Sony's 3D 'Popeye' forward". Variety. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ↑ Keegan, Rebecca (August 25, 2012). "Genndy Tartakovsky gets 'Hotel Transylvania' open for business". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (November 9, 2012). "'Hotel Transylvania 2' in the Works for 2015 Release". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ↑ Jardine, William (May 17, 2013). "Sony Pushes Genndy Tartakovsky's Popeye Back to 2015". A113Animation. Retrieved May 22, 2013.

- ↑ Kit, Borys (March 12, 2014). "Sony Animation Sets Slate: 'Smurfs', 'Transylvania 2,' More (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ↑ McMillan, Graeme (September 18, 2014). "Sony Pictures Releases First Glimpse of Genndy Tartakovsky's 'Popeye'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ Han, Angie (March 13, 2015). "Genndy Tartakovsky Exits Sony’s ‘Popeye’". /Film. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ Khatchatourian, Maane (March 14, 2015). "Sony’s ‘Popeye’ Loses Director Genndy Tartakovsky". Variety. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ↑ Jaafar, Ali (January 22, 2016). "Sony Pictures Animation Brings In T. J. Fixman To Write ‘Popeye’". deadline.com.

- ↑ "Iwata Asks: New Super Mario Bros. Wii – Mario Couldn't Jump At First". Nintendo. Retrieved July 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Leading the Animation Conversation » Popeyes in Puerto Rico". Cartoon Brew. April 24, 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Wimpy Burger – Junk Food Heath Advice – Wimpy Burgers, learn the truth". wimpyburgers.co.uk.

- ↑ "Popeye Spinach". Popeye Spinach. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Popeye's Supplements Canada ~ Over 120 Locations Across Canada! - History". popeyescanada.com.

- ↑ Punchy packaging for Popeye energy drink | Food And Beverage News. Fandbnews.com (January 30, 2013). Retrieved on March 29, 2013.

- ↑ Club mascots (in Portuguese). Flamengo official website. Retrieved January 18, 2010.

- ↑ Namco Games.

- ↑ Grandinetti, p. 4.

- ↑ Gregory, Ted (17 January 2004). "Popeye's home fussin', fightin' A Downstate town that gave birth 75 years ago to the spinach-chompin' sailor is in a Bluto-type of brawl". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- ↑ Popeye: The First Fifty Years. New York: Workman Publishing. Pages 44–45.

- ↑ Blackbeard, Bill, "The First (arf, arf!) Superhero of Them All". In Dick Lupoff & Don Thompson, ed., All In Color For A Dime Arlington House, 1970.

- ↑ "Management of Shoulder Impingement Syndrome and Rotator Cuff Tears – February 15, 1998 – American Family Physician". Aafp.org. February 15, 1998. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Guideline not published". Guideline.gov. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ Action Comics #421 at OddballComics.com.

- ↑ Superman and Cap'n Strong at the Quarter Bin.

- ↑ O'Connor, John J. "Who Framed Roger Rabbit – Trailer – Cast – Showtimes – NYTimes.com". Movies.nytimes.com. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ Robert Pruter. Chicago Soul. p. 196.

- ↑ "Various Artists - New Orleans Popeye Party". allmusic.com. Retrieved June 11, 2017.

- ↑ Bill Blackbeard, "The First (arf, arf) Superhero of Them All". In All in Color for a Dime, ed. by Dick Lupoff and Don Thompson, Ace, 1970.

- ↑ Glen Weldon; Michael Kantor. Superheroes!:Capes cowls and the creation of comic book culture. p. 16.

- ↑ Hewitt, Katie (August 16, 2010) How to win the kids v. veggies battle, Toronto Globe and Mail

- ↑ "No Eats Me Spinach!". Cagle.com. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ Hamblin, T.J. (1981). "Fake". BMJ. 283 (6307): 1671–4. PMC 1507475

. PMID 6797607. doi:10.1136/bmj.283.6307.1671.

. PMID 6797607. doi:10.1136/bmj.283.6307.1671. - ↑ Gabbatt, Adam (December 8, 2009). "E.C. Segar, Popeye's creator, celebrated with a Google doodle". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ della Quercia, Jacopo (May 3, 2010). "The 7 Most Disastrous Typos Of All Time". Cracked.com. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ↑ Archived October 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- ↑ Arbesman, Samuel (September 27, 2012) Paradox of Hoaxes: How Errors Persist, Even When Corrected. wired.com

- ↑ Jeep. wordorigins.org

- ↑ "Chester, Illinois :|: Official Website". Popeye Picnic. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ "Welcome to King Features Syndicate". Kingfeatures.com. November 17, 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2009.

- ↑ "July 29, 2015 Popeye comic strip". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved July 29, 2015.

- ↑ "July 30, 2015 Popeye comic strip". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved July 30, 2015.

- ↑ "July 28, 2011 Popeye comic strip". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved July 28, 2011.

- ↑ "October 1, 2011 Popeye comic strip". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ↑ "October 3, 2011 Popeye comic strip". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

Further reading

- Grandinetti, Fred M. Popeye: An Illustrated Cultural History. 2nd ed. McFarland, 2004. ISBN 0-7864-1605-X

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Popeye |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Popeye. |