Thermal Battery

|

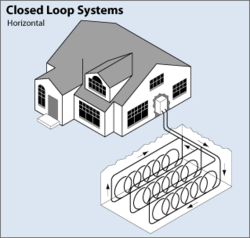

Small residential thermal battery example. This is an unencapsulated thermal battery for storing thermal energy formed by burying pipes in an area of earth -- commonly referred to as a GHEX or Geothermal Heat Exchanger. Photo courtesy IGSHPA. | |

| Type | Energy |

|---|---|

| Working principle | Thermodynamics |

| Invented | Heat pumps, as used by the GHEX depicted above, were invented in the 1940s by Robert C. Webber. |

| First production | Heat pumps were first produced in the 1970s. |

A thermal energy battery is a physical structure used for the purpose of storing and releasing thermal energy—see also thermal energy storage. Such a thermal battery (a.k.a. TBat) allows energy available at one time to be temporarily stored and then released at another time. The basic principles involved in a thermal battery occur at the atomic level of matter, with energy being added to or taken from either a solid mass or a liquid volume which causes the substance's temperature to change. Some thermal batteries also involve causing a substance to transition thermally through a phase transition which causes even more energy to be stored and released due to the delta enthalpy of fusion or delta enthalpy of vaporization.

History of thermal batteries

Thermal batteries are very common, and include such familiar items as a hot water bottle. Early examples of thermal batteries would include stone and mud cook stoves, rocks placed in fires, and kilns. While stoves and kilns are ovens, then are also thermal storage systems that depend on heat being retained for an extended period of time.

Types of thermal batteries

Thermal batteries generally fall into 4 categories:

- GHEX thermal batteries

- Encapsulated thermal batteries

- Phase change thermal batteries

- Other thermal batteries

These 4 types of batteries are each unique in their form and application, although fundamentally all are for the storage and retrieval of thermal energy. They also differ in method and density of heat storage. A description of each type of thermal battery follows.

GHEX thermal battery - unencapsulated

A ground heat exchanger (GHEX) is an area of the earth that is utilized as an annual cycle thermal battery. These thermal batteries are areas of the earth into which pipes have been placed in order to transfer thermal energy; they are "unencapsulated" in the sense that the target area is not insulated from the rest of the surrounding earth. Energy is added to the GHEX by running a higher temperature fluid through the pipes and thus raising the temperature of the local earth. Energy can also be taken from the GHEX by running a lower temperature fluid through those same pipes.

GHEX thermal batteries are implemented in two forms. The picture above depicts what is known as a "horizontal" GHEX where trenching is used to place an amount of pipe in a closed loop in the ground. They are also formed by drilling boreholes into the ground, either vertically or horizontally, and then the pipes are inserted in the form of a closed-loop with a "u-bend" fitting on the far end of the loop. These drilled GHEX thermal batteries are also sometimes called "borehole thermal energy storage systems".

Heat energy can be added to or removed from a GHEX thermal battery at any point in time. However, they are most often used on an annual cycle where energy is extracted from a building during the summer season to cool a building and added to the GHEX, and then that same energy is later extracted from the GHEX in the winter season to heat the building. This annual cycle of energy addition and subtraction is highly predictable based on energy modeling of the building served. A thermal battery used in this mode is a renewable energy source as the energy extracted in the winter will be restored to the GHEX the next summer in a continually repeating cycle. This type is solar powered because it is the heat from the sun in the summer that is removed from a building and stored in the ground for use in the next winter season for heating.

Phase change thermal battery

Phase change materials used for thermal storage are capable of storing and releasing significant thermal capacity at the temperature that they change phase. These materials are chosen based on specific applications because there is a wide range of temperatures that may be useful in different applications and a wide range of materials that change phase at different temperatures. These materials include salts and waxes that are specifically engineered for the applications they serve. In addition to manufactured materials, water is a phase change material. The latent heat of water is 334 joules/gram. The phase change of water occurs at 0°C (32°F).

Some applications use the thermal capacity of water or ice as cold storage; others use it as heat storage. It can serve either application; ice can be melted to store heat then refrozen to warm an environment which is below freezing (putting liquid water at 0°C in such an environment warms it much more than the same mass of ice at the same temperature, because the latent heat of freezing is extracted from it, which is why the phase change is relevant), or water can be frozen to "store cold" then melted to make an environment above freezing colder (and again, a given mass of ice at 0°C will provide more cooling than the same mass of water at the same temperature).

The advantage of using a phase change in this way is that a given mass of material can absorb a large quantity of energy without its temperature changing. Hence a thermal battery that uses a phase change can be made lighter, or more energy can be put into it without raising the internal temperature unacceptably.

Encapsulated thermal battery

An encapsulated thermal battery is physically similar to a phase change thermal battery in that it is a confined amount of physical material which is thermally heated or cooled to store or extract energy. However, in a non-phase change encapsulated thermal battery the temperature of the substance is changed without inducing a phase change. Since a phase change is not needed many more materials are available for use in an encapsulated thermal battery.

One of the key properties of an encapsulated thermal battery is its volumetric heat capacity (VHC), also termed volume-specific heat capacity. Typical substances used for these thermal batteries include water, concrete, and wet sand.

An example of an encapsulated thermal battery is a residential water heater with a storage tank.[1][2] This thermal battery is usually slowly charged over a period of about 30–60 minutes for rapid use when needed (e.g., 10–15 minutes). Many utilities, understanding the "thermal battery" nature of water heaters, have begun using them to absorb excess renewable energy power when available for later use by the homeowner. According to the above cited article,[1] "net savings to the electricity system as a whole could be $200 per year per heater – some of which may be passed on to its owner".

Other thermal batteries

There are some other items that have historically been termed "thermal batteries". In this group is the molten salt battery which is a device for generating electricity. Other examples include the heat packs that skiers use for keeping hands and feet warm (see hand warmer). These are a chemical battery which when activated (with air in this case) will produce heat. Other related chemical thermal batteries exist for producing cold (see instant cold pack) generally used for sport injuries.

The one common principle of these other thermal batteries is that the reaction involved is generally not reversible. Thus, these batteries are not used for storing and retrieving heat energy.

See also

- Thermal energy storage

- Seasonal thermal energy storage

- Ground-coupled heat exchanger

- Geothermal heat pump

- International Ground Source Heat Pump Association

- Steam accumulator

References

- 1 2 Your home water heater may soon double as a battery, Washington Post, February 24, 2016, By Chris Mooney

- ↑ The Hidden Battery: Opportunities in Electric Water Heating, The Brattle Group, Prepared for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA) and the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), January 2016, by Ryan Hledik, Judy Chang, Roger Lueken