Theories of urban planning

Planning theory is the body of scientific concepts, definitions, behavioral relationships, and assumptions that define the body of knowledge of urban planning. There are eight procedural theories of planning that remain the principal theories of planning procedure today: the rational-comprehensive approach, the incremental approach, the transactive approach, the communicative approach, the advocacy approach, the equity approach, the radical approach, and the humanist or phenomenological approach.[1]

Background

The modern origins of urban planning lie in the movement for urban reform that arose as a reaction against the disorder of the industrial city in the mid-19th century. Urban planning exists in various forms and it addresses many different issues.[2] Urban planning can include urban renewal, by adapting urban planning methods to existing cities suffering from decline. Alternatively, it can concern the massive challenges associated with urban growth, particularly in the Global South.[3]

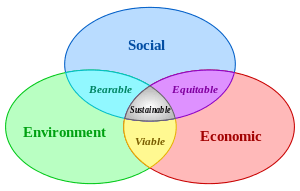

In the late 20th century, the term sustainable development has come to represent an ideal outcome in the sum of all planning goals.[4]

Blueprint planning

Following the rise of empiricism during the industrial revolution, the rational planning movement (1890–1960) emphasized the improvement of the built environment based on key spatial factors. Examples of these factors include: exposure to direct sunlight, movement of vehicular traffic, standardized housing units, and proximity to green-space.[5] To identify and design for these spatial factors, rational planning relied on a small group of highly specialized technicians, including architects, urban designers, and engineers. Other, less common, but nonetheless influential groups included governmental officials, private developers, and landscape architects. Through the strategies associated with these professions, the rational planning movement developed a collection of techniques for quantitative assessment, predictive modeling, and design. Due to the high level of training required to grasp these methods, however, rational planning fails to provide an avenue for public participation. In both theory and practice, this shortcoming opened rational planning to claims of elitism and social insensitivity.

Although it can be seen as an extension of the sort of civic pragmatism seen in Oglethorpe's plan for Savannah or William Penn's plan for Philadelphia, the roots of the rational planning movement lie in Britain's Sanitary Movement (1800-1890).[6] During this period, advocates such as Charles Booth and Ebenezer Howard argued for central organized, top-down solutions to the problems of industrializing cities. In keeping with the rising power of industry, the source of planning authority in the Sanitary Movement included both traditional governmental offices and private development corporations. In London and its surrounding suburbs, cooperation between these two entities created a network of new communities clustered around the expanding rail system.[7] Two of the best examples of these communities are Letchworth in Hertfordshire and Hampstead Garden Suburb in Greater London. In both communities, architects Raymond Unwin and Richard Barry Parker exemplify the elite, top-down approach associated with the rational planning movement by using the planning process to establish a uniform landscape and architectural style based on an idealized medieval village.

From Britain, the rational planning movement spread out across the world. In areas undergoing industrialization themselves, British influences combined with local movements to create unique reinterpretations of the rational planning process. In Paris, architect Le Corbusier adopted rational planning's centralized approach and added to it a dedication to quantitative assessment and a love for the automobile. Together, these two factors yielded the influential planning aesthetic known as "Tower in the Park". In the United States, Frank Lloyd Wright similarly identified vehicular mobility as a principal planning metric. However, where Le Corbusier emphasized design through quantitative assessment of spatial processes, Wright identified the insights of local public technicians as the key design criteria. Wright's Broadacre City provides a vivid expression of what this landscape might look like.

Throughout both the United States and Europe, the rational planning movement declined in the later half of the 20th century.[8] The reason for the movement's decline was also its strength. By focusing so much on design by technical elites, rational planning lost touch with the public it hoped to serve. Key events in this decline in the United States include the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis and the national backlash against urban renewal projects, particularly urban expressway projects.[9]

Synoptic planning

After the “fall” of blueprint planning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the synoptic model began to emerge as a dominant force in planning. Lane (2005) describes synoptic planning as having four central elements:

- "(1) an enhanced emphasis on the specification of goals and targets; (2) an emphasis on quantitative analysis and predication of the environment; (3) a concern to identify and evaluate alternative policy options; and (4) the evaluation of means against ends (page 289)."[10]

Public participation was first introduced into this model and it was generally integrated into the system process described above. However, the problem was that the idea of a single public interest still dominated attitudes, effectively devaluing the importance of participation because it suggests the idea that the public interest is relatively easy to find and only requires the most minimal form of participation.[10]

Blueprint and synoptic planning both employ what is called the rational paradigm of planning. The rational model is perhaps the most widely accepted model among planning practitioners and scholars, and is considered by many to be the orthodox view of planning. As its name clearly suggests, the goal of the rational model is to make planning as rational and systematic as possible. Proponents of this paradigm would generally come up with a list of steps that the planning process can be at least relatively neatly sorted out into and that planning practitioners should go through in order when setting out to plan in virtually any area. As noted above, this paradigm has clear implications for public involvement in planning decisions.[10]

Participatory planning

Participatory planning is an urban planning paradigm that emphasizes involving the entire community in the strategic and management processes of urban planning; or, community-level planning processes, urban or rural. It is often considered as part of community development.[11] Participatory planning aims to harmonize views among all of its participants as well as prevent conflict between opposing parties. In addition, marginalized groups have an opportunity to participate in the planning process.[12]

Incrementalism

Beginning in the late 1950s and early 1960s, critiques of the rational paradigm began to emerge and formed into several different schools of planning thought. The first of these schools is Lindblom’s incrementalism. Lindblom describes planning as “muddling through” and thought that practical planning required decisions to be made incrementally. This incremental approach meant choosing from small number of policy approaches that can only have a small number consequences and are firmly bounded by reality, constantly adjusting the objectives of the planning process and using multiple analyses and evaluations.[13] Lane (2005) explains the public involvement implications of this philosophy. Though this perspective of planning could be considered a large step forward in that it recognizes that there are number of “public interests” and because it provides room for the planning process to be less centralized and incorporate the voices other than those of planners, it in practice would only allow for the public to be involved in a minimal, more reactive rather than proactive way.[10]

Mixed scanning model

The mixed scanning model, developed by Etzioni, takes a similar, but slightly different approach. Etzioni (1968) suggested that organizations plan on two different levels: the tactical and the strategic. He posited that organizations could accomplish this by essentially scanning the environment on multiple levels and then choose different strategies and tactics to address what they found there. While Lindblom’s approach only operated on the functional level Etzioni argued, the mixed scanning approach would allow planning organizations to work on both the functional and more big-picture oriented levels.[14] Lane explains though, that this model does not do much more at improving public involvement since the planner or planning organization is still at its focus and since its goal is not necessarily to achieve consensus or reconcile differing points of view on a particular subject.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, planners began to look for new approaches because as happened nearly a decade before, it was realized that the current models were not necessarily sufficient. As had happened before, a number of different models emerged. Lane (2005) notes that it is most useful to think of these model as emerging from a social transformation planning tradition as opposed to a social guidance one, so the emphasis is more bottom-up in nature than it is top-down.[10]

Transactive planning

Transactive planning was a radical break from previous models. Instead of considering public participation as method that would be used in addition to the normal training planning process, participation was a central goal. For the first time, the public was encouraged to take on an active role in the policy setting process, while the planner took on the role of a distributor of information and a feedback source.[10] Transactive planning focuses on interpersonal dialogue that develops ideas, which will be turned into action. One of the central goals is mutual learning where the planner gets more information on the community and citizens become more educated about planning issues.[15]

Advocacy planning

Formulated in the 1960s by lawyer and planning scholar Paul Davidoff, the advocacy planning model takes the perspective that there are large inequalities in the political system and in the bargaining process between groups that result in large numbers of people unorganized and unrepresented in the process. It concerns itself with ensuring that all people are equally represented in the planning process by advocating for the interests of the underprivileged and seeking social change.[16][17] Again, public participation is a central tenet of this model. A plurality of public interests is assumed, and the role of planner is essentially the one as a facilitator who either advocates directly for underrepresented groups directly or encourages them to become part of the process.[10]

Bargaining model

The bargaining model views planning as the result of give and take on the part of a number of interests who are all involved in the process. It argues that this bargaining is the best way to conduct planning within the bounds of legal and political institutions.[18] The most interesting part of this theory of planning is that makes public participation the central dynamic in the decision-making process. Decisions are made first and foremost by the public, and the planner plays a more minor role.[10]

Communicative approach

The communicative approach to planning is perhaps the most difficult to explain. It focuses on using communication to help different interests in the process understand each other. The idea is that each individual will approach a conversation with his or her own subjective experience in mind and that from that conservation shared goals and possibilities will emerge. Again, participation plays a central role under this model. The model seeks to include as a broad range of voice to enhance the debate and negotiation that is supposed to form the core of actual plan making. In this model, participation is actually fundamental to the planning process happening. Without the involvement of concerned interests there is no planning.[10]

Looking at each of these models it becomes clear that participation is not only shaped by the public in a given area or by the attitude of the planning organization or planners that work for it. In fact, public participation is largely influenced by how planning is defined, how planning problems are defined, the kinds of knowledge that planners choose to employ and how the planning context is set.[10] Though some might argue that is too difficult to involve the public through transactive, advocacy, bargaining and communicative models because transportation is some ways more technical than other fields, it is important to note that transportation is perhaps unique among planning fields in that its systems depend on the interaction of a number of individuals and organizations.[19]

Process

Prior to 1950, Urban Planning was seldom considered a unique profession in Canada.[20] There were, and are, of course, differences from country to country. For example, the UK's Royal Town Planning Institute was created as a professional organisation in 1914 and given a Royal Charter in 1959. Town planning focused on top-down processes by which the urban planner created the plans. The planner would know architecture, surveying, or engineering, bringing to the town planning process ideals based on these disciplines. They typically worked for national or local governments. Urban planners were seen as generalists, capable of integrating the work of other disciplines into a coherent plan for whole cities or parts of cities. A good example of this kind of planner was Lewis Keeble and his standard textbook, Principles and Practice of Town and Country Planning, published in 1951.[21]

Changes to the planning process

Strategic Urban Planning over past decades have witnessed the metamorphosis of the role of the urban planner in the planning process. More citizens calling for democratic planning & development processes have played a huge role in allowing the public to make important decisions as part of the planning process. Community organizers and social workers are now very involved in planning from the grassroots level.[22] The term advocacy planning was coined by Paul Davidoff in his influential 1965 paper, "Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning" which acknowledged the political nature of planning and urged planners to acknowledge that their actions are not value-neutral and encouraged minority and under represented voices to be part of planning decisions.[23] Benveniste argued that planners had a political role to play and had to bend some truth to power if their plans were to be implemented.[24]

Developers have also played huge roles in development, particularly by planning projects. Many recent developments were results of large and small-scale developers who purchased land, designed the district and constructed the development from scratch. The Melbourne Docklands, for example, was largely an initiative pushed by private developers to redevelop the waterfront into a high-end residential and commercial district.

Recent theories of urban planning, espoused, for example by Salingaros see the city as an adaptive system that grows according to process similar to those of plants. They say that urban planning should thus take its cues from such natural processes.[25] Such theories also advocate participation by inhabitants in the design of the urban environment, as opposed to simply leaving all development to large-scale construction firms.[26]

In the process of creating an urban plan or urban design, carrier-infill is one mechanism of spatial organization in which the city's figure and ground components are considered separately. The urban figure, namely buildings, are represented as total possible building volumes, which are left to be designed by architects in following stages. The urban ground, namely in-between spaces and open areas, are designed to a higher level of detail. The carrier-infill approach is defined by an urban design performing as the carrying structure that creates the shape and scale of the spaces, including future building volumes that are then infilled by architects' designs. The contents of the carrier structure may include street pattern, landscape architecture, open space, waterways, and other infrastructure. The infill structure may contain zoning, building codes, quality guidelines, and Solar Access based upon a solar envelope.[27][28] Carrier-Infill urban design is differentiated from complete urban design, such as in the monumental axis of Brasília, in which the urban design and architecture were created together.

In carrier-infill urban design or urban planning, the negative space of the city, including landscape, open space, and infrastructure is designed in detail. The positive space, typically building site for future construction, are only represented as unresolved volumes. The volumes are representative of the total possible building envelope, which can then be infilled by individual architects.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "How Planners Use Planning Theory". Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ↑ Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Duineveld, M., De Jong, H. (2012) Co-evolutions of planning and design. Planning Theory 12(2): 177-192

- ↑ James, Paul; Holden, Meg; Lewin, Mary; Neilson, Lyndsay; Oakley, Christine; Truter, Art; Wilmoth, David (2013). "Managing Metropolises by Negotiating Mega-Urban Growth". In Harald Mieg and Klaus Töpfer. Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development. Routledge.

- ↑ Wheeler, Stephen (2004). "Planning Sustainable and Livable Cities", Routledge; 3rd edition.

- ↑ Hall, Peter (2008). The Cities of Tomorrow. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 13–141. ISBN 978-0-631-23252-0.

- ↑ Hall, Peter (2008). The Cities of Tomorrow. Publishing: Blackwell. pp. 13–47, 87–141. ISBN 978-0-631-23252-0.

- ↑ Hall, Peter (2008). The Cities of Tomorrow. Publishing: Blackwell. pp. 48–86. ISBN 978-0-631-23252-0.

- ↑ Allmendinger, Philip (2002). Planning Futures: New Directions for Planning Theory. Routledge. pp. 20–25.

- ↑ Black, William R. Transportation: A Geographical Analysis. The Guilford Press. p. 29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Lane, M. B. (2005). Public Participation in Planning: An Intellectual History. Australian Geographer , 36 (3), 283–299

- ↑ Lefevre, Pierre; Kolsteren, Patrick; De Wael, Marie-Paule; Byekwaso, Francis; Beghin, Ivan (December 2000). "Comprehensive Participatory Planning and Evaluation" (PDF). Antwerp, Belgium: IFAD. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ [McTague, C. & Jakubowski, S. Marching to the beat of a silent drum: Wasted consensus-building and failed neighborhood participatory planning. Applied Geography 44, 182–191 (2013)]

- ↑ Lindblom, C. E. (1959). The science of "muddling through". Public Administration Review, 19 (2), 79–88.

- ↑ Etzioni, A. (1968). The active society: a theory of societal and political rocesses. New York: Free Press.

- ↑ Friedman, J. (1973). Retracking America: A Theory of Transactive Planning. Garden City, NJ: Anchor Press/Doubleday.

- ↑ Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 31 (4), 331–338.

- ↑ Mazziotti, D. F. (1982). The underlying assumptions of advocacy planning: pluralism and reform. In C. Paris (Ed.), Critical readings in planning theory (pp. 207–227) New York: Pergamon Press.

- ↑ McDonald, G. T. (1989). Rural Land Use Planning Decisions by Bargaining. Journal of Rural Studies, 5 (4), 325–335.

- ↑ Wachs, M. (2004). Reflections on the planning process. In S. Hansen, & G. Guliano (Eds.), The Geography of Urban Transportation (3rd Edition ed., pp. 141–161). The Guilford Press.

- ↑ Hodge, Gerald and Gordon, David Planning Canadian Communities (fifth edition), Nelson College Indigenous, 2007

- ↑ Keeble, Lewis B. (1951) Principles and Practice of Town and Country Planning, Estates Gazette, London

- ↑ Forester John. "Planning in the Face of Conflict", 1987, ISBN 0-415-27173-8, Routledge, New York.

- ↑ "Advocacy and Community Planning: Past, Present and Future". Planners Network. Retrieved 2014-08-11.

- ↑ Benveniste, Guy (1994). Mastering the Politics of Planning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- ↑ ""Life and the geometry of the environment", Nikos Salingaros, November 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-11.

- ↑ "P2P Urbanism", collection of articles by Nikos Salingaros and others

- ↑ Capeluto, I. G. and Shaviv, E. On the Use of 'Solar Volume' for Determining the Urban Fabric. Solar Energy Vol. 70, No. 3, pp. 275–280, 2001.

- ↑ Nelson, Nels O. Planning the Productive City, 2009, accessed December 30, 2010.

Bibliography

- Allmendinger, Phil and Michael Gunder, 2005, "Applying Lacanian Insight and a Dash of Derridean Deconstruction to Planning's 'Dark Side'," Planning Theory, vol. 4, pp. 87–112.

- Atmospheric Environment Volume 35, Issue 10, April 2001, Pages 1717–1727. "Traffic pollution in a downtown site of Buenos Aires City"

- Garvin, Alexander (2002). The American City: What Works and What Doesn't. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-137367-5. (A standard text for many college and graduate courses in city planning in America)

- Dalley, Stephanie, 1989, Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, the Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others, Oxford World's Classics, London, pp. 39–136

- Gunder, Michael, 2003, "Passionate Planning for the Others' Desire: An Agonistic Response to the Dark Side of Planning," Progress in Planning, Vol. 60, no. 3, October, pp. 235–319.

- Hoch, Charles, Linda C. Dalton and Frank S. So, editors (2000). The Practice of Local Government Planning, Intl City County Management Assn; 3rd edition. ISBN 0-87326-171-2 (The "Green Book")

- James, Paul; Holden, Meg; Lewin, Mary; Neilson, Lyndsay; Oakley, Christine; Truter, Art; Wilmoth, David (2013). "Managing Metropolises by Negotiating Mega-Urban Growth". In Harald Mieg and Klaus Töpfer. Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development. Routledge.

- Kemp, Roger L. and Carl J. Stephani (2011). "Cities Going Green: A Handbook of Best Practices." McFarland and Co., Inc., Jefferson, NC, USA, and London, England, UK. ISBN 978-0-7864-5968-1.

- Oke, T. R. (1982). "The energetic basis of the urban heat island". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 108: 1–24.

- Pløger, John, 2001, "Public Participation and the Art of Governance," Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 219–241.

- Roy, Ananya, 2008, "Post-Liberalism: On the Ethico-Politics of Planning," Planning Theory, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 92–102.

- Santamouris, Matheos (2006). Environmental Design of Urban Buildings: An Integrated Approach.

- Shrady, Nicholas, The Last Day: Wrath, Ruin & Reason in The Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755, Penguin, 2008, ISBN 978-0-14-311460-4

- Tang, Wing-Shing, 2000, "Chinese Urban Planning at Fifty: An Assessment of the Planning Theory Literature," Journal of Planning Literature, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 347–366.

- Tunnard, Christopher and Boris Pushkarev (1963). Man-Made America: Chaos or Control?: An Inquiry into Selected Problems of Design in the Urbanized Landscape, New Haven: Yale University Press. (This book won the National Book Award, strictly America; a time capsule of photography and design approach.)

- Wheeler, Stephen (2004). "Planning Sustainable and Livable Cities", Routledge; 3rd edition.

- Yiftachel, Oren, 1995, "The Dark Side of Modernism: Planning as Control of an Ethnic Minority," in Sophie Watson and Katherine Gibson, eds., Postmodern Cities and Spaces (Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell), pp. 216–240.

- Yiftachel, Oren, 1998, "Planning and Social Control: Exploring the Dark Side," Journal of Planning Literature, vol. 12, no. 4, May, pp. 395–406.

- Yiftachel, Oren, 2006, "Re-engaging Planning Theory? Towards South-Eastern Perspectives," Planning Theory, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 211–222.

Further reading

- Urban Planning, 1794-1918: An International Anthology of Articles, Conference Papers, and Reports, Selected, Edited, and Provided with Headnotes by John W. Reps, Professor Emeritus, Cornell University.

- City Planning According to Artistic Principles, Camillo Sitte, 1889

- Missing Middle Housing: Responding to the Demand for Walkable Urban Living by Daniel Parolek of Opticos Design, Inc., 2012

- Kemp, Roger L. and Carl J. Stephani (2011). "Cities Going Green: A Handbook of Best Practices." McFarland and Co., Inc., Jefferson, NC, USA, and London, England, UK. (ISBN 978-0-7864-5968-1).

- Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, Ebenezer Howard, 1898

- The Improvement of Towns and Cities, Charles Mulford Robinson, 1901

- Town Planning in practice, Raymond Unwin, 1909

- The Principles of Scientific Management, Frederick Winslow Taylor, 1911

- Cities in Evolution, Patrick Geddes, 1915

- The Image of the City, Kevin Lynch, 1960

- The Concise Townscape, Gordon Cullen, 1961

- The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs, 1961

- The City in History, Lewis Mumford, 1961

- The City is the Frontier, Charles Abrams, Harper & Row Publishing, New York, 1965.

- A Pattern Language, Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa and Murray Silverstein, 1977

- What Do Planners Do?: Power, Politics, and Persuasion, Charles Hoch, American Planning Association, 1994. ISBN 978-0-918286-91-8

- Planning the Twentieth-Century American City, Christopher Silver and Mary Corbin Sies (Eds.), Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996

- "The City Shaped: Urban Patterns and Meanings Through History", Spiro Kostof, 2nd Edition, Thames and Hudson Ltd, 1999 ISBN 978-0-500-28099-7

- The American City: A Social and Cultural History, Daniel J. Monti, Jr., Oxford, England and Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 1999. 391 pp. ISBN 978-1-55786-918-0.

- Urban Development: The Logic Of Making Plans, Lewis D. Hopkins, Island Press, 2001. ISBN 1-55963-853-2

- ''Readings in Planning Theory, 4th edition, Susan Fainstein and James DeFilippis, Oxford, England and Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, 2016.

- Taylor, Nigel, (2007), Urban Planning Theory since 1945, London, Sage.

- Planning for the Unplanned: Recovering from Crises in Megacities, by Aseem Inam (published by Routledge USA, 2005).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Urban planning. |