Theil–Sen estimator

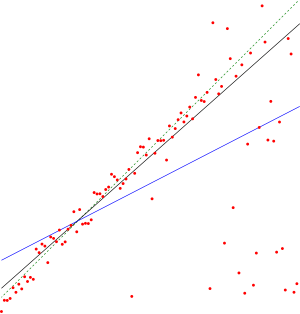

In non-parametric statistics, there is a method for robustly fitting a line to a set of points (simple linear regression) that chooses the median of the slopes of all lines through pairs of two-dimensional sample points. It has been called the Theil–Sen estimator, Sen's slope estimator,[1][2] slope selection,[3][4] the single median method,[5] the Kendall robust line-fit method,[6] and the Kendall–Theil robust line.[7] It is named after Henri Theil and Pranab K. Sen, who published papers on this method in 1950 and 1968 respectively, and after Maurice Kendall.

This estimator can be computed efficiently, and is insensitive to outliers. It can be significantly more accurate than non-robust simple linear regression for skewed and heteroskedastic data, and competes well against non-robust least squares even for normally distributed data in terms of statistical power.[8] It has been called "the most popular nonparametric technique for estimating a linear trend".[2]

Definition

As defined by Theil (1950), the Theil–Sen estimator of a set of two-dimensional points (xi,yi) is the median m of the slopes (yj − yi)/(xj − xi) determined by all pairs of sample points. Sen (1968) extended this definition to handle the case in which two data points have the same x-coordinate. In Sen's definition, one takes the median of the slopes defined only from pairs of points having distinct x-coordinates.

Once the slope m has been determined, one may determine a line from the sample points by setting the y-intercept b to be the median of the values yi − mxi.[9] As Sen observed, this estimator is the value that makes the Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient comparing the values of xi with the residual for the i-th observation become approximately zero.[10]

A confidence interval for the slope estimate may be determined as the interval containing the middle 95% of the slopes of lines determined by pairs of points,[11] and may be estimated quickly by sampling pairs of points and determining the 95% interval of the sampled slopes. According to simulations, approximately 600 sample pairs are sufficient to determine an accurate confidence interval.[8]

Variations

A variation of the Theil–Sen estimator due to Siegel (1982) determines, for each sample point (xi,yi), the median mi of the slopes (yj − yi)/(xj − xi) of lines through that point, and then determines the overall estimator as the median of these medians.

A different variant pairs up sample points by the rank of their x-coordinates (the point with the smallest coordinate being paired with the first point above the median coordinate, etc.) and computes the median of the slopes of the lines determined by these pairs of points.[12]

Variations of the Theil–Sen estimator based on weighted medians have also been studied, based on the principle that pairs of samples whose x-coordinates differ more greatly are more likely to have an accurate slope and therefore should receive a higher weight.[13]

For seasonal data, it may be appropriate to smooth out seasonal variations in the data by considering only pairs of sample points that both belong to the same month or the same season of the year, and finding the median of the slopes of the lines determined by this more restrictive set of pairs.[14]

Statistical properties

The Theil–Sen estimator is an unbiased estimator of the true slope in simple linear regression.[15] For many distributions of the response error, this estimator has high asymptotic efficiency relative to least-squares estimation.[16] Estimators with low efficiency require more independent observations to attain the same sample variance of efficient unbiased estimators.

The Theil–Sen estimator is more robust than the least-squares estimator because it is much less sensitive to outliers. It has a breakdown point of , meaning that it can tolerate arbitrary corruption of up to 29.3% of the input data-points without degradation of its accuracy.[9] However, the breakdown point decreases for higher-dimensional generalizations of the method.[17] A higher breakdown point, 50%, holds for a different robust line-fitting algorithm, the repeated median estimator of Siegel.[9]

The Theil–Sen estimator is equivariant under every linear transformation of its response variable, meaning that transforming the data first and then fitting a line, or fitting a line first and then transforming it in the same way, both produce the same result.[18] However, it is not equivariant under affine transformations of both the predictor and response variables.[17]

Algorithms

The median slope of a set of n sample points may be computed exactly by computing all O(n2) lines through pairs of points, and then applying a linear time median finding algorithm. Alternatively, it may be estimated by sampling pairs of points. This problem is equivalent, under projective duality, to the problem of finding the crossing point in an arrangement of lines that has the median x-coordinate among all such crossing points.[19]

The problem of performing slope selection exactly but more efficiently than the brute force quadratic time algorithm has been extensively studied in computational geometry. Several different methods are known for computing the Theil–Sen estimator exactly in O(n log n) time, either deterministically[3] or using randomized algorithms.[4] Siegel's repeated median estimator can also be constructed efficiently in the same time bound.[20] In models of computation in which the input coordinates are integers and bitwise operations on integers take constant time, the problem can be solved even more quickly, in randomized expected time .[21]

An estimator for the slope with approximately median rank, having the same breakdown point as the Theil–Sen estimator, may be maintained in the data stream model (in which the sample points are processed one by one by an algorithm that does not have enough persistent storage to represent the entire data set) using an algorithm based on ε-nets.[22]

Applications

Theil–Sen estimation has been applied to astronomy due to its ability to handle censored regression models.[23] In biophysics, Fernandes & Leblanc (2005) suggest its use for remote sensing applications such as the estimation of leaf area from reflectance data due to its "simplicity in computation, analytical estimates of confidence intervals, robustness to outliers, testable assumptions regarding residuals and ... limited a priori information regarding measurement errors". For measuring seasonal environmental data such as water quality, a seasonally adjusted variant of the Theil–Sen estimator has been proposed as preferable to least squares estimation due to its high precision in the presence of skewed data.[14] In computer science, the Theil–Sen method has been used to estimate trends in software aging.[24] Another application of the Theil-Sen test is in meteorology and climatology. [25] The test is used to estimate the long-term trends of wind speed and occurrence.

See also

- Regression dilution, for another problem affecting estimated trend slopes

Notes

- ↑ Gilbert (1987).

- 1 2 El-Shaarawi & Piegorsch (2001).

- 1 2 Cole et al. (1989); Katz & Sharir (1993); Brönnimann & Chazelle (1998).

- 1 2 Dillencourt, Mount & Netanyahu (1992); Matoušek (1991); Blunck & Vahrenhold (2006).

- ↑ Massart et al. (1997).

- ↑ Sokal & Rohlf (1995); Dytham (2011).

- ↑ Granato (2006)

- 1 2 Wilcox (2001).

- 1 2 3 Rousseeuw & Leroy (2003), pp. 67, 164.

- ↑ Osborne (2008).

- ↑ For determining confidence intervals, pairs of points must be sampled with replacement; this means that the set of pairs used in this calculation includes pairs in which both points are the same as each other. These pairs are always outside the confidence interval, because they do not determine a well-defined slope value, but using them as part of the calculation causes the confidence interval to be wider than it would be without them.

- ↑ De Muth (2006).

- ↑ Jaeckel (1972); Scholz (1978); Sievers (1978); Birkes & Dodge (1993).

- 1 2 Hirsch, Slack & Smith (1982).

- ↑ Sen (1968), Theorem 5.1, p. 1384; Wang & Yu (2005).

- ↑ Sen (1968), Section 6; Wilcox (1998).

- 1 2 Wilcox (2005).

- ↑ Sen (1968), p. 1383.

- ↑ Cole et al. (1989).

- ↑ Matoušek, Mount & Netanyahu (1998).

- ↑ Chan & Pătraşcu (2010).

- ↑ Bagchi et al. (2007).

- ↑ Akritas, Murphy & LaValley (1995).

- ↑ Vaidyanathan & Trivedi (2005).

- ↑ Romanić D. Ćurić M- Jovičić I. Lompar M. 2015. Long-term trends of the ‘Koshava’ wind during the period 1949–2010. International Journal of Climatology 35(2):288-302. DOI:10.1002/joc.3981.

References

- Akritas, Michael G.; Murphy, Susan A.; LaValley, Michael P. (1995), "The Theil-Sen estimator with doubly censored data and applications to astronomy", Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90 (429): 170–177, JSTOR 2291140, MR 1325124, doi:10.1080/01621459.1995.10476499.

- Bagchi, Amitabha; Chaudhary, Amitabh; Eppstein, David; Goodrich, Michael T. (2007), "Deterministic sampling and range counting in geometric data streams", ACM Transactions on Algorithms, 3 (2): Art. No. 16, MR 2335299, arXiv:cs/0307027

, doi:10.1145/1240233.1240239.

, doi:10.1145/1240233.1240239. - Birkes, David; Dodge, Yadolah (1993), "6.3 Estimating the Regression Line", Alternative Methods of Regression, Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics, 282, Wiley-Interscience, pp. 113–118, ISBN 978-0-471-56881-0.

- Blunck, Henrik; Vahrenhold, Jan (2006), "In-place randomized slope selection", International Symposium on Algorithms and Complexity, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 3998, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, pp. 30–41, ISBN 978-3-540-34375-2, MR 2263136, doi:10.1007/11758471_6.

- Brönnimann, Hervé; Chazelle, Bernard (1998), "Optimal slope selection via cuttings", Computational Geometry Theory and Applications, 10 (1): 23–29, MR 1614381, doi:10.1016/S0925-7721(97)00025-4.

- Chan, Timothy M.; Pătraşcu, Mihai (2010), "Counting inversions, offline orthogonal range counting, and related problems", Proceedings of the Twenty-First Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms (SODA '10) (PDF), pp. 161–173.

- Cole, Richard; Salowe, Jeffrey S.; Steiger, W. L.; Szemerédi, Endre (1989), "An optimal-time algorithm for slope selection", SIAM Journal on Computing, 18 (4): 792–810, MR 1004799, doi:10.1137/0218055.

- De Muth, E. James (2006), Basic Statistics and Pharmaceutical Statistical Applications, Biostatistics, 16 (2nd ed.), CRC Press, p. 577, ISBN 978-0-8493-3799-4.

- Dillencourt, Michael B.; Mount, David M.; Netanyahu, Nathan S. (1992), "A randomized algorithm for slope selection", International Journal of Computational Geometry & Applications, 2 (1): 1–27, MR 1159839, doi:10.1142/S0218195992000020.

- Dytham, Calvin (2011), Choosing and Using Statistics: A Biologist's Guide (3rd ed.), John Wiley and Sons, p. 230, ISBN 978-1-4051-9839-4.

- El-Shaarawi, Abdel H.; Piegorsch, Walter W. (2001), Encyclopedia of Environmetrics, Volume 1, John Wiley and Sons, p. 19, ISBN 978-0-471-89997-6.

- Fernandes, Richard; Leblanc, Sylvain G. (2005), "Parametric (modified least squares) and non-parametric (Theil–Sen) linear regressions for predicting biophysical parameters in the presence of measurement errors", Remote Sensing of Environment, 95 (3): 303–316, doi:10.1016/j.rse.2005.01.005.

- Gilbert, Richard O. (1987), "6.5 Sen's Nonparametric Estimator of Slope", Statistical Methods for Environmental Pollution Monitoring, John Wiley and Sons, pp. 217–219, ISBN 978-0-471-28878-7.

- Granato, Gregory E. (2006), Kendall-Theil Robust Line (KTRLine--version 1.0)-A visual basic program for calculating and graphing robust nonparametric estimates of linear-regression coefficients between two continuous variables, Techniques and Methods of the U.S. Geological Survey, book 4, chap. A7, U.S. Geological Survey, pp. 31 with CD–ROM.

- Hirsch, Robert M.; Slack, James R.; Smith, Richard A. (1982), "Techniques of trend analysis for monthly water quality data", Water Resources Research, 18 (1): 107–121, Bibcode:1982WRR....18..107H, doi:10.1029/WR018i001p00107.

- Jaeckel, Louis A. (1972), "Estimating regression coefficients by minimizing the dispersion of the residuals", Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 43 (5): 1449–1458, MR 0348930, doi:10.1214/aoms/1177692377.

- Katz, Matthew J.; Sharir, Micha (1993), "Optimal slope selection via expanders", Information Processing Letters, 47 (3): 115–122, MR 1237287, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(93)90234-Z.

- Massart, D. L.; Vandeginste, B. G. M.; Buydens, L. M. C.; De Jong, S.; Lewi, P. J.; Smeyers-Verbeke, J. (1997), "12.1.5.1 Single median method", Handbook of Chemometrics and Qualimetrics: Part A, Data Handling in Science and Technology, 20A, Elsevier, pp. 355–356, ISBN 978-0-444-89724-4.

- Matoušek, Jiří (1991), "Randomized optimal algorithm for slope selection", Information Processing Letters, 39 (4): 183–187, MR 1130747, doi:10.1016/0020-0190(91)90177-J.

- Matoušek, Jiří; Mount, David M.; Netanyahu, Nathan S. (1998), "Efficient randomized algorithms for the repeated median line estimator", Algorithmica, 20 (2): 136–150, MR 1484533, doi:10.1007/PL00009190.

- Osborne, Jason W. (2008), Best Practices in Quantitative Methods, Sage Publications, Inc., p. 273, ISBN 9781412940658.

- Rousseeuw, Peter J.; Leroy, Annick M. (2003), Robust Regression and Outlier Detection, Wiley Series in Probability and Mathematical Statistics, 516, Wiley, p. 67, ISBN 978-0-471-48855-2.

- Scholz, Friedrich-Wilhelm (1978), "Weighted median regression estimates", The Annals of Statistics, 6 (3): 603–609, JSTOR 2958563, MR 0468054, doi:10.1214/aos/1176344204.

- Sen, Pranab Kumar (1968), "Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall's tau", Journal of the American Statistical Association, 63 (324): 1379–1389, JSTOR 2285891, MR 0258201, doi:10.2307/2285891.

- Siegel, Andrew F. (1982), "Robust regression using repeated medians", Biometrika, 69 (1): 242–244, doi:10.1093/biomet/69.1.242.

- Sievers, Gerald L. (1978), "Weighted rank statistics for simple linear regression", Journal of the American Statistical Association, 73 (363): 628–631, JSTOR 2286613, doi:10.1080/01621459.1978.10480067.

- Sokal, Robert R.; Rohlf, F. James (1995), Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research (3rd ed.), Macmillan, p. 539, ISBN 978-0-7167-2411-7.

- Theil, H. (1950), "A rank-invariant method of linear and polynomial regression analysis. I, II, III", Nederl. Akad. Wetensch., Proc., 53: 386–392, 521–525, 1397–1412, MR 0036489.

- Vaidyanathan, Kalyanaraman; Trivedi, Kishor S. (2005), "A Comprehensive Model for Software Rejuvenation", IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, 2 (2): 124–137, doi:10.1109/TDSC.2005.15.

- Wang, Xueqin; Yu, Qiqing (2005), "Unbiasedness of the Theil–Sen estimator", Journal of Nonparametric Statistics, 17 (6): 685–695, MR 2165096, doi:10.1080/10485250500039452.

- Wilcox, Rand R. (1998), "A note on the Theil–Sen regression estimator when the regressor Is random and the error term Is heteroscedastic", Biometrical Journal, 40 (3): 261–268, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-4036(199807)40:3<261::AID-BIMJ261>3.0.CO;2-V.

- Wilcox, Rand R. (2001), "Theil–Sen estimator", Fundamentals of Modern Statistical Methods: Substantially Improving Power and Accuracy, Springer-Verlag, pp. 207–210, ISBN 978-0-387-95157-7.

- Wilcox, Rand R. (2005), "10.2 Theil–Sen Estimator", Introduction to Robust Estimation and Hypothesis Testing, Academic Press, pp. 423–427, ISBN 978-0-12-751542-7.

External links

- Kendall-Theil Robust Line (KTRLine—version 1.0) public-domain Visual Basic software for Theil–Sen estimation published by the United States Geological Survey