Aspidochelone

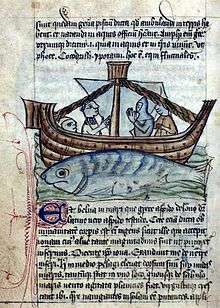

According to the tradition of the Physiologus and medieval bestiaries, the aspidochelone is a fabled sea creature, variously described as a large whale or vast sea turtle, and a giant sea monster with huge spines on the ridge of its back. No matter what form it is, it is always described as being huge where it is often mistaken for an island and appears to be rocky with crevices and valleys with trees and greenery and having sand dunes all over it. The name aspidochelone appears to be a compound word combining Greek aspis (which means either "asp" or "shield"), and chelone, the turtle. It rises to the surface from the depths of the sea, and entices unwitting sailors with its island appearance to make landfall on its huge shell and then the whale is able to pull them under the ocean, ship and all the people, drowning them. It also emits a sweet smell that lures fish into its trap where it then devours them. In the moralistic allegory of the Physiologus and bestiary tradition, the aspidochelone represents Satan, who deceives those whom he seeks to devour.[1][2]

Accounts of seafarers' encounters with gigantic fish appear in various other works, including the Book of Jonah, The Adventures of Pinocchio, and the Baron Munchausen stories.

In the Physiologus

One version of the Latin text of the Physiologus reads:

- "There is a monster in the sea which in Greek is called aspidochelone, in Latin "asp-turtle"; it is a great whale, that has what appear to be beaches on its hide, like those from the sea-shore. This creature raises its back above the waves of the sea, so that sailors believe that it is just an island, so that when they see it, it appears to them to be a sandy beach such as is common along the sea-shore. Believing it to be an island, they beach their ship alongside it, and disembarking, they plant stakes and tie up the ships. Then, in order to cook a meal after this work, they make fires on the sand as if on land. But when the monster feels the heat of these fires, it immediately submerges into the water, and pulls the ship into the depths of the sea.

Such is the fate of all who pay no heed to the Devil and his wiles, and place their hopes in him: tied to him by their works, they are submerged into the burning fire of Gehenna: for such is his guile."[3]

In The Whale

A similar tale is told by the Old English poem The Whale, where the monster appears under the name Fastitocalon. This is apparently a variant of Aspidochelone, and the name given to the Devil. The poem has an unknown author, and is one of three poems in the Old English Physiologus, also known as the Bestiary, in the Exeter Book, folio 96b-97b, that are allegorical in nature, the other two being The Phoenix and The Panther.[4] The Exeter book is now in the Exeter Cathedral library. The book has suffered from multiple mutilations and it is possible that some of the manuscript is missing. It is believed that the book had been used as a “beer mat”, a cutting board, and suffered other types of mutilation by its previous owners. The Physiologus has gone through many different translations into many different languages throughout the world. It is possible that the content has also been changed throughout the centuries.

- Nu ic fitte gen ymb fisca cynn

wille woðcræfte wordum cyþan

þurh modgemynd bi þam miclan hwale.

Se bið unwillum oft gemeted,

frecne ond ferðgrim, fareðlacendum,

niþþa gehwylcum; þam is noma cenned,

fyrnstreama geflotan, Fastitocalon.

- Is þæs hiw gelic hreofum stane,

swylce worie bi wædes ofre,

sondbeorgum ymbseald, særyrica mæst,

swa þæt wenaþ wægliþende

þæt hy on ealond sum eagum wliten,

ond þonne gehydað heahstefn scipu

to þam unlonde oncyrrapum . . .

- "This time I will with poetic art rehearse, by means of words and wit, a poem about a kind of fish, the great sea-monster which is often unwillingly met, terrible and cruel-hearted to seafarers, yea, to every man; this swimmer of the ocean-streams is known as the asp-turtle.

His appearance is like that of a rough boulder, as if there were tossing by the shore a great ocean-reedbank begirt with sand-dunes, so that seamen imagine they are gazing upon an island, and moor their high-prowed ships with cables to that false land, make fast the ocean-coursers at the sea's end, and, bold of heart, climb up."

- "This time I will with poetic art rehearse, by means of words and wit, a poem about a kind of fish, the great sea-monster which is often unwillingly met, terrible and cruel-hearted to seafarers, yea, to every man; this swimmer of the ocean-streams is known as the asp-turtle.

The moral of the story remains the same:

- Swa bið scinna þeaw,

deofla wise, þæt hi drohtende

þurh dyrne meaht duguðe beswicað,

ond on teosu tyhtaþ tilra dæda. . .

- "Such is the way of demons, the wont of devils: they spend their lives in outwitting men by their secret power, inciting them to the corruption of good deeds, misguiding . . ."[5]

In The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, J. R. R. Tolkien made a little verse that claimed the name "Fastitocalon" from The Whale, and told a similar story:

- Look, there is Fastitocalon!

An island good to land upon,

Although 'tis rather bare.

Come, leave the sea! And let us run,

Or dance, or lie down in the sun!

See, gulls are sitting there!

Beware!

As such, Tolkien imported the traditional tale of the aspidochelone into the lore of his Middle-earth.

Sources of the story

Pliny the Elder's Natural History tells the story of a giant fish, which he names pristis, of immense size.[6]

The allegory of the Aspidochelone borrows from the account of whales in Saint Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae. Isidore cites the prophet Jonah; the Vulgate translation of the Book of Jonah translates Jonah 2:2 as Exaudivit me de ventre inferni: "He (the Lord) heard me from the belly of Hell". He concludes that such whales must have bodies as large as mountains.[7]

It is also called different names in different cultures. It has been mentioned in traveler’s myth and lore in Greece, Egypt, throughout Europe, and in the Latin world. In these cultures, the beast was known to look as the deceptive island that lured travelers to be pulled down into their drowning deaths.

In the folklore of the Inuit of Greenland, there was a similar monster called an Imap Umassoursa. It was a giant sea monster that often was mistaken for a vast and flat island. When the monster emerged from the water, it would tip sailors into freezing waters, causing their deaths. Whenever the waters seemed shallow, the sailors would tread carefully for fear of being over that dreadful creature.

In Irish folklore, there was a giant fish of a monster that breached the boat of Saint Brendan. It was called the Jasconius. It was also mistaken for a vast island.

Zaratan is another name given to the Aspidochelone. This is the name for the monster that is used mostly in the Middle East. It is used in the Middle Eastern Physiologus and is in Arab and Islamic legends. It is mentioned in “The Wonders of Creation”, by the Al Qaswini in Persia and in the “Book of Animals” by a Spanish naturalist named Miguel Palacios. It is also mentioned in the first voyage of Sinbad the Sailor in the “Tales of the Thousand and One Nights”.

In Chile, there is a giant sea monster named Cuero, or Hide. It is a vast and flat thing that looks like stretched out animal hide that devours every living thing that it comes in contact with. It is also known to lure sailors to their death.[8]

Jasconius

A similar monster appears in the Legend of Saint Brendan, where it was called Jasconius.[9] Because of its size, Brendan and his fellow voyagers mistake it for an island and land to make camp. They celebrate Easter on the sleeping giant's back, but awaken it when they light their campfire. They race to their ship, and Brendan explains that the moving island is really Jasconius, who labors unsuccessfully to put his tail in its mouth.[10]

The same tale of a sea monster that is mistaken for an island is told in the first voyage of Sinbad the Sailor in The Book of One Thousand and One Nights.[11]

Appearances in modern fiction

- The name Jasconius is used for the whale in the children's book The Adventures of Louey and Frank by Carolyn White. She attributes the name to having grown up with the legend of Brendan.[12]

- The popular Magic: The Gathering card game also features a card named Island Fish Jasconius, the art of which is a massive fish bearing tropical foliage on its back.

- Both The Adventures of Baron Munchausen and Sinbad: Legend of the Seven Seas have the heroes coming across an island that reveals to be a huge anglerfish looking sea monster.

- In The NeverEnding Story, the giant turtle Morla is an Island Turtle that lives in the Swamp of Sadness.

- The film Aladdin and the King of Thieves featured the Vanishing Isle that is a giant marble fortress on the back of a giant sea turtle that periodically rises from the ocean and goes back underwater. This is where the Hand of Midas was located.

- In the video game The Legend of Zelda: Majora's Mask, the player Link rides to the Great Bay Temple on the back of a giant sea turtle that resembles a small island.

- In the (MMORPG) Final Fantasy XI, Aspidochelone is a rare spawn of the monster Adamantoise both of which are giant turtles.

- The Digimon franchise had their own versions of the Aspidochelone in the form of Ebonwumon (a two-headed turtle Digimon Sovereign with a tree on its back), ElDradimon (who has a city on its back), and KingWhamon (who bares the Island Zone on the top of its head).

- In Yu-Gi-Oh!, the Island Turtle is a water creature.

- The asp-turtle make an appearance in Naruto, where Naruto Uzumaki goes to train before a big battle. This version of the asp-turtle is a little different. It does not lure the travelers to their death. It works with them so they are not discovered. It also floats in the sea and is constantly moving. However, it is a giant turtle with the appearance of an island. Killer B has a house on the Island Turtle and there are apes living there.

- The third and final season of Avatar: The Last Airbender featured a giant island turtle called the Lion-Turtle (voiced by Kevin Michael Richardson). Upon ending up on its back and learning that the island is actually the Lion Turtle, Aang was trained in the technique of Energybending by the Lion Turtle. The Energybending that Aang learned from the Lion-Turtle came in handy during Aang's fight with Fire Lord Ozai.

- In The Legend of Korra (a sequel to Avatar: The Last Airbender), in the ancient past there were a number of Lion-Turtles, each with a city of humans on their back that they protected from the dangerous spirits roaming the world. There were many Lion-Turtles in the past until they were all hunted into near-extinction. Whenever humans left the city, the Lion-Turtle would use energybending to give them one of the four types of elemental bending to defend themselves, and then they would return it when they came back to the city. The street-urchin Wan was the first to steal fire from a Fire Lion-Turtle (voiced by Jim Cummings) simply by not returning it when he was supposed to as seen in "Beginnings" Pt. 1 and "Beginnings" Pt. 2. When he was exiled for bringing fire into the city, the Fire Lion-Turtle allowed Wan to keep it so he could protect himself in the wilds sometime before he became an Avatar. Besides the Fire Lion-Turtle, there was also the flying Air Lion-Turtle (voiced by Stephen Stanton), the Earth Lion-Turtle, and the Water Lion-Turtle.

- In the One Piece film The Giant Mechanical Soldier of Karakuri Castle, Mecha Island is a type of Island Turtle that awakens every thousand years to lay its eggs.

- The multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) World of Warcraft's fourth expansion pack Mists of Pandaria introduced a new zone The Wandering Isle, set on the back of a roaming giant turtle named Shen-zin Su, where pandaren player characters begin their adventure. The turtle's origins lie with the pandaren explorer Lui Lang, who was overcome with wanderlust, a rare trait in the pandaren of that time. Because of this he departed the pandaren continent of Pandaria around 10,000 years ago, riding on the back of the then man-sized turtle, Shen-zin Su. Lui Lang later returned to his homeland a few times, and each time the turtle had become progressively bigger. By the time players encounter Shen-zin Su, the turtle has grown to the size of a small continent, complete with fertile farmlands, mountains, lakes and a thriving population of pandaren, animals and plant life. In addition to serving as a home and method of transportation for his inhabitants, Shen-zin Su is a fully sapient being and quite aware of the Wandering Isle pandaren that have been living on his back for generations.

- The official lyric video for From Finner by Of Monsters and Men depicts a large whale-like creature swimming with a city on its back, with the lyrics hinting that the titular "Finner" could be the creature itself.

See also

References

- ↑ Rose, Carol: Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth (Norton, 2001; ISBN 0-393-32211-4)

- ↑ J. R. R. Tolkien, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, no. 255; Humphrey Carpenter and Christopher Tolkien, eds. (Allen & Unwin, 1981; ISBN 0-261-10265-6)

- ↑ Est belua in mare quae dicitur graece aspidochelone, latine autem aspido testudo; cetus ergo est magnus, habens super corium suum tamquam sabulones, sicut iuxta littora maris. Haec in medio pelago eleuat dorsum suum super undas maris sursum; ita ut nauigantibus nautis non aliud credatur esse quam insula, praecipue cum uiderint totum locum illum sicut in omnibus littoribus maris sabulonibus esse repletum. Putantes autem insulam esse, applicant nauem suam iuxta eam, et descendentes figunt palos et alligant naues; deinde ut coquant sibi cibos post laborem, faciunt ibi focos super arenam quasi super terram; illa uero belua, cum senserit ardorem ignis, subito mergit se in aquam, et nauem secum trahit in profundum maris.

Sic patiuntur omnes qui increduli sunt et quicumque ignorant diaboli astutias, spem suam ponentes in eum; et operibus eius se obligantes, simul merguntur cum illo in gehennam ignis ardentis: ita astutia eius.

Anonymous, Physiologus Latinus versio B. Accessed Nov. 19, 2007. Translation for Wikipedia. - ↑ Albert Stanburrough Cook, ed. (1821). The Old English Physiologus. Volume 63 of Yale studies in English. Verse translated by James Hall Pitman. Yale university press. p. 23.

- ↑ Albert S. Cook, The Old English Physiologus (Project Gutenberg online version, 2004)

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Historia Naturalis, book 9, ch. 4 (Latin)

- ↑ Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae XII:6 (Latin), accessed Nov. 18, 2007

- ↑ Rose, Carol: Giants, Monsters, and Dragons: An Encyclopedia of Folklore, Legend, and Myth (Norton, 2001; ISBN 0-393-32211-4)

- ↑ Iannello, Fausto: Jasconius rivelato. Studio comparativo del simbolismo religioso dell’”isola-balena” nella Navigatio sancti Brendani (Edizioni dell’Orso, Biblioteca di studi storico-religiosi 9, Alessandria 2013 - ISBN 978-88-6274-447-8).

- ↑ Anonymous, Navigatio sancti Brendani abbatis, ch. 11, 23. (Latin), accessed Nov. 18, 2007

- ↑ Anonymous, The Book of One Thousand and One Nights, ss. 538-539 (Burton translation)

- ↑ Interview with Carolyn White Archived December 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.. harperchildrens.com. Retrieved March 14, 2007.