West Yorkshire Regiment

| West Yorkshire Regiment | |

|---|---|

Badge of the West Yorkshire Regiment | |

| Active | 1685–1958 |

| Country |

|

| Branch |

|

| Size |

1–3 Regular Battalions |

| Garrison/HQ |

Bradford Moor Barracks (1873–1878) Imphal Barracks, York (1878–1958) |

| Nickname(s) | Calvert's Entire, The Old and Bold |

| Motto(s) |

Nec Aspera Terrent (Afraid Of No Hardships) |

| March | Ça Ira |

| Anniversaries | Imphal (22 June) |

| Engagements |

Namur Fontenoy Falkirk Culloden Brandywine |

The West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales's Own) (14th Foot) was an infantry regiment of the British Army. In 1958 it amalgamated with the East Yorkshire Regiment (15th Foot) to form the Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire which was, on 6 June 2006, amalgamated with the Green Howards and the Duke of Wellington's Regiment (West Riding) to form the Yorkshire Regiment (14th/15th, 19th and 33rd/76th Foot).

History

The regiment was raised by Sir Edward Hales in 1685, by order of King James II. One of the nine new regiments of foot, raised to meet the Monmouth Rebellion it was termed Hales's Regiment.[1] The regiment served in Flanders between 1693 and 1696 and gained its first battle honour at Namur in 1695.[2]

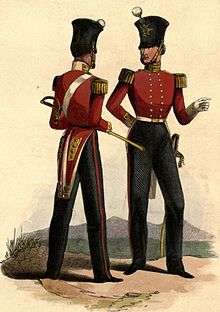

1715 saw the regiment moved to Scotland to fight the Jacobite risings.[3] In 1727 the regiment played a major part in defending Gibraltar against the Spanish, where it remained garrisoned for the next 15 years.[4] 1745 saw the regiment in Flanders fighting at Fontenoy before being recalled to Scotland by Cumberland to fight the '45 Rebellion.[5] Fighting at Falkirk and Culloden,[6] it became the 14th of Foot in 1751.[7] The regiment returned to Gibraltar in 1751 for another 8-year stay.[8] In 1765, when stationed at Windsor, it was granted royal permission for the grenadiers to wear bearskin caps with the White Horse of Hanover signifying the favour of the King.[9]

In 1766, the regiment left Portsmouth for North America and was stationed in Nova Scotia.[10]

The 14th although at the ready in their barracks did not play a part in the Boston Massacre. Captain Thomas (29th Foot) was the officer of the day in charge of the duty detail (29th of Foot) that faced the crowds outside of the Customs House. The crowd that gathered began taunting the detail until a shot, then volley was fired into the crowd, three civilians were killed outright and two more died later. Captain Preston and the detail went to trial and were successfully defended by Lawyer John Adams thus ending tensions between the crown and the citizens of Boston for the time being. The 14th would remain part of the Boston Garrison until 1772.[11]

American War of Independence

In 1772, the 14th arrived in St Vincent as part of the force to subjugate the maroons. Due to bush fighting and disease the regiment was depleted in numbers, it stayed for two years and was then scheduled to return to England in 1774. Due to the rising tensions in the colonies the regiment's return was cancelled and instead it was redeployed piecemeal, under Major Jonathan Furlong to St. Augustine, Florida and Providence Island in the Bahamas.[10]

At dawn on 1 January 1776, the fleet opened fire on Norfolk. Between the firing (burning) of the buildings and the fleet firing on the town, Norfolk burned for three days, 863 buildings were destroyed. After the fleet left, the rebels reoccupied what remained of the town but soon decided to burn even that to keep Lord Dunmore from using it. After all was said and done, 1,298 buildings were destroyed and the 5th largest city in colonial America ceased to exist.[12]

After Norfolk, the fleet left for Turkey Point near Portsmouth where it would base operations. While at Turkey Point there were a series of small raids and skirmishes. The fleet would stay at Turkey point only until late May when it would leave for Gwynn's Island. In August, the fleet withdrew from the Chesapeake and headed to New York. The 14th was withdrawn from service, it being severely under strength from disease and battle in both the Caribbean and Virginia. In New York the remaining men of the regiment were used to supplement other regiments in the area. The officers were sent back to Britain to recruit a new regiment.[13]

In 1777, while in training in England, one company each of the 14th and the 15th regiments were placed under the command of Col. Patrick Ferguson and sent to America to test the concept of the rifle company with the Colonel's new rifle. The rifle companies fought well at the battle of Brandywine in Pennsylvania on 11 September. After the experimental rifle companies returned to England they were made the light companies of their respective regiments; thus ended the 14th Regiment's participation in the American Revolution.[14]

In 1782 the 14th was named The 14th (Bedfordshire) Regiment. The outbreak of the French Revolution and the subsequent French invasion of the Low Countries led to a British force commanded by the Duke of York being sent to join troops of the Imperial Austrian army. The 14th distinguished themselves in numerous actions, at Famars and Valenciennes in 1793 and at Tournai in 1794, for which they were subsequently granted the battle honour 'Tournay.' At the Battle of Famars in order to encourage the men, Lieutenant-Colonel Welbore Ellis Doyle, the commanding officer, ordered the band of the 14th to play

the French revolutionary song “Ça Ira”.[15] This was subsequently chosen as the Regimental march. In the final, unsuccessful attempt to check the French invasion of the Netherlands, the 14th also suffered heavy casualties in the hard-fought rearguard action at Geldermalsen on 8 January 1795. There followed the disastrous winter retreat into Germany. Returning to England the following May, the Regiment was then posted to the West Indies where it was on duty until 1803. In February 1797 the regiment participated in the bloodless invasion of Trinidad.[16]

Napoleonic Wars

_British_lines_under_fire.jpg)

The outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars in 1803 led to the expansion of the British Army. The 14th formed a second battalion in Belfast in 1804, and a third battalion in 1813. The 1st Battalion spent much of the war on garrison duty in Bengal. In 1809 the Regiment was re-titled The 14th (Buckinghamshire) Regiment.[7] The 1st Battalion served in India for 25 years until 1831. During this period the 1st Battalion took part in campaigns against the French in Mauritius in 1810, and the Dutch in Java in 1811, with Java adding another Battle Honour.[17]

In 1808-9, the 2nd Battalion joined the Peninsular Army and gained the Battle honour Corunna.[18] The 2nd Battalion saw service in the Walcheren Campaign and was disbanded in 1817.[19] The 3rd Battalion fought at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815; it was disbanded in 1816.[20]

The Victorian era

The 14th then was posted to the West Indies, Canada and Malta. In 1855 the Regiment served in the Crimean war. In 1876 the Prince of Wales presented new Colours to the 1st Battalion and conferred on the 14th the honoured title of The Prince of Wales's Own. A second battalion was again raised in 1858 and took part in the New Zealand Wars and the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[21]

The regiment was not fundamentally affected by the Cardwell Reforms of the 1870s, which gave it a depot at Bradford Moor Barracks from 1873, or by the Childers reforms of 1881 – as it already possessed two battalions, there was no need for it to amalgamate with another regiment.[22] The regiment moved to Imphal Barracks in York in 1878.[23] Under the reforms the regiment became The Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) on 1 July 1881.[24]

Second Boer War

1899 saw the 2nd Battalion sent to the Second Boer War 1899–1902 in South Africa and after a number of engagements two members of the Battalion were awarded the Victoria Cross: Captain (later Colonel) Mansel-Jones in February 1900,[25] and Sergeant Traynor in February 1901.[26] The 4th (Militia) Battalion was embodied in December 1899, and 500 officers and men left for South Africa in February 1900.[27] The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Volunteer Battalions sent service companies to the Boer War and were granted the battle honour South Africa 1900–02.[28][29]

Early 20th century

In 1908, the Volunteers and Militia were reorganised nationally, with the former becoming the Territorial Force and the latter the Special Reserve;[30] the regiment now had two Reserve and four Territorial battalions:

- 1st (V) Bn became 5th Bn (TF), with RHQ at Colliergate in York.[31][32]

- 2nd (V) Bn became 6th Bn (TF), with RHQ at Belle Vue Barracks in Bradford (since demolished).[28][32]

- 3rd (V) Bn became 7th and 8th (Leeds Rifles) Bns (TF), a double battalion with RHQ at Carlton Barracks in Leeds.[29][32]

First World War

Regular Army

The 1st Battalion landed at Saint-Nazaire as part of the 18th Brigade in the 6th Division in September 1914 for service on the Western Front.[31] The 2nd Battalion landed at Le Harve as part of the 23rd Brigade in the 8th Division in November 1914 also for service on the Western Front.[31]

Territorial Force

The 1/5th, 1/6th, 1/7th and 1/8th Battalions landed at Boulogne-sur-Mer as part of the West Riding Brigade in the West Riding Division in April 1915 also for service on the Western Front.[31] The 2/5th, 2/6th, 2/7th and 2/8th Battalions landed at Le Havre as part of the 185th (2/1st West Riding) Brigade in the 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division in January 1917 also for service on the Western Front.[31]

New Armies

The 9th (Service) Battalion landed at Suvla Bay in Gallipoli as part of the 32nd Brigade in the 11th (Northern) Division in August 1915; the battalion was evacuated from Gallipoli in January 1916 and landed in Marseille in July 1916 for service on the Western Front.[31] The 10th (Service) Battalion landed at Boulogne-sur-Mer as part of the 50th Brigade in the 17th (Northern) Division in July 1915 for service on the Western Front.[31] The 11th (Service) Battalion landed at Le Havre as part of the 69th Brigade in the 23rd Division in August 1915 for service on the Western Front and then transferred to Italy in November 1917.[31] The 12th (Service) Battalion landed at Le Havre as part of the 63rd Infantry Brigade in the 21st Division in September 1915 also for service on the Western Front.[31]

The 15th (Service) Battalion (1st Leeds), raised by the Lord Mayor and City of Leeds, and the 16th (Service) Battalion (1st Bradford), raised by the Lord Mayor and City of Bradford, landed in Egypt as part of the 93rd Brigade in the 31st Division in December 1915 and then moved to France in March 1916 for service on the Western Front.[31] The 17th (Service) Battalion (2nd Leeds), raised by the Lord Mayor and City of Leeds, landed at Le Havre as part of the 106th Brigade in the 35th Division in February 1916 for service on the Western Front.[31] The 18th (Service) Battalion (2nd Bradford), raised by the Lord Mayor and City of Bradford, landed in Egypt as part of the 93rd Brigade in the 31st Division in December 1915 and then moved to France in March 1916 for service on the Western Front.[31] The 21st (Service) Battalion (Wool Textile Pioneers) landed in France as pioneer battalion to the 4th Division in June 1916 also for service on the Western Front.[31]

Inter-war years

In 1936 the 8th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion transferred to the Royal Artillery as 66th (Leeds Rifles, The West Yorkshire Regiment) Anti-Aircraft Brigade.[29][33]

In 1937 the 6th Battalion became 49th (The West Yorkshire Regiment) Anti-Aircraft Battalion of the Royal Engineers, converting to a searchlight regiment of the Royal Artillery in 1940.[28][34]

In April 1938 the 7th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion converted to the armoured role as 45th (Leeds Rifles) Bn, Royal Tank Regiment. In June 1939, the company at Morley was split off to form the cadre for a duplicate unit, the 51st (Leeds Rifles) Bn, Royal Tank Regiment.[29][35]

Second World War

Both the 1st and 2nd battalions of the West Yorks served in the Far East throughout the Burma Campaign, fighting in the British Fourteenth Army. The 2nd Battalion served with the 9th Indian Infantry Brigade from November 1940.[36]

In 1942 2/5th Battalion West Yorkshire Regiment was converted to armour, becoming 113th Regiment Royal Armoured Corps. As with all infantry battalions converted in this way, they continued to wear their West Yorkshire cap badge on the black beret of the RAC.[37]

51st (Leeds Rifles) Royal Tank Regiment, formed as a 2nd Line duplicate of 45th (Leeds Rifles) Royal Tank Regiment (previously the 7th (Leeds Rifles) Battalion of the West Yorks), served in 25th Army Tank Brigade in the Italian campaign under the command of Brigadier Noel Tetley of the Leeds Rifles, who was the only Territorial Army RTR officer to command a brigade on active service. The regiment distinguished itself in support of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division in the assault on the Hitler Line in May 1944. At the request of the Canadians, 51 RTR adopted the Maple Leaf as an additional badge, which is still worn by its successors, the Leeds Detachment (Leeds Rifles), Imphal (PWO) Company, The East and West Riding Regiment.[35]

Postwar years

In 1948 the 1st and 2nd Battalions were amalgamated and were stationed in Austria. They then moved to Egypt and on to Malaya. After a tour of duty in Northern Ireland in 1955–56, the 1st Battalion took part in the Suez Operation and was then stationed in Dover until the amalgamation in July 1958.[38]

In 1956 the merged 45th/51st (Leeds Rifles) RTR returned to the infantry role as 7th (Leeds Rifles) Bn West Yorkshire Regt and in 1961 it re-absorbed the 466th (Leeds Rifles) Light Anti-Aircraft Regt, RA, to form The Leeds Rifles, The Prince of Wales's Own Regiment of Yorkshire.[29]

Battle honours

The regiment's battle honours were as follows:[7]

- Namur 1695, Tournay, Corunna, India, Java, Waterloo, Bhurtpore, Sevastopol, New Zealand, Afghanistan 1879–80, Relief of Ladysmith, South Africa 1899–1902 (South Africa 1900–02 for Volunteer Battalions)

- The Great War [31 battalions]: Aisne 1914 '18, Armentières 1914, Neuve Chapelle, Aubers, Hooge 1915, Loos, Somme 1916 '18, Albert 1916 '18, Bazentin, Pozières, Flers-Courcelette, Morval, Thiepval, Le Transloy, Ancre Heights, Ancre 1916, Arras 1917 '18, Scarpe 1917 '18, Bullecourt, Hill 70, Messines 1917 '18, Ypres 1917 '18, Pilckem, Langemarck 1917, Menin Road, Polygon Wood, Poelcappelle, Passchendaele, Cambrai 1917 '18, St. Quentin, Rosières, Villers Bretonneux, Lys, Hazebrouck, Bailleul, Kemmel, Marne 1918, Tardenois, Amiens, Bapaume 1918, Drocourt-Quéant, Hindenburg Line, Havrincourt, Épéhy, Canal du Nord, Selle, Valenciennes, Sambre, France and Flanders 1914–18, Piave, Vittorio Veneto, Italy 1917–18, Suvla, Landing at Suvla, Scimitar Hill, Gallipoli 1915, Egypt 1915–16

- The Second World War: North-West Europe 1940, Jebel Dafeis, Keren, Ad Teclesan, Abyssinia 1940–41, Cauldron, Defence of Alamein Line, North Africa 1940–42, Pegu 1942, Yenangyaung 1942, North Arakan, Maungdaw, Defence of Sinzweya, Imphal, Bishenpur, Kanglatongbi, Meiktila, Capture of Meiktila, Defence of Meiktila, Rangoon Road, Pyawbwe, Sittang 1945, Burma 1942–45

- 7th Bn (Leeds Rifles) wore a Maple Leaf badge in commemoration of the assault on the Adolf Hitler Line, and bore the badge of the Royal Tank Regiment with dates '1942–45' and two scrolls inscribed 'North Africa' and 'Italy' as an honorary distinction on the colours and appointments.[39]

Victoria Crosses

The following members of the Regiment were awarded the Victoria Cross:

- Captain (later Colonel) Conwyn Mansel-Jones, Second Boer War

- Sergeant William Bernard Traynor, Second Boer War

- Private William Boynton Butler, Great War

- Corporal (later Major) Samuel Meekosha, Great War

- Sergeant Albert Mountain, Great War

- Corporal (later Captain) George Sanders, Great War

- Acting Sergeant Hanson Victor Turner, Second World War

Colonels-in-Chief

- 1947: Maj-Gen. HRH Princess Mary, The Princess Royal, CI, GCVO, GBE, RRC, TD

Colonels of the Regiment

Colonels of the regiment included:[7]

- 1685–1688: Lt-Gen. Sir Edward Hales, 3rd Baronet

- 1688–1692: Col. William Beveridge

- 1692–1713: Lt-Gen. John Tidcomb

- 1713–1743: Lt-Gen. Jasper Clayton

- 1743–1747: Brig-Gen. John Price

- 1747–1753: Maj-Gen. Hon. William Herbert

14th Regiment of Foot

- 1753–1755: Maj-Gen. Edward Braddock

- 1755–1756: Lt-Gen. Thomas Fowke

- 1756–1765: Maj-Gen. Charles Jeffereys

- 1765–1775: Lt-Gen. Hon. William Keppel

- 1775–1787: Gen. The Rt. Hon. Robert Cuninghame, 1st Baron Rossmore, PC

14th (Bedfordshire) Regiment of Foot

- 1787–1789: Lt-Gen. John Douglas

- 1789: Col. George Waldegrave, 4th Earl Waldegrave

- 1789–1806: Gen. George Hotham

- 1806–1826: Gen. Sir Harry Calvert, 1st Baronet, GCB, GCH

14th (Buckinghamshire) Regiment

- 1826–1834: Gen. Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch, GCB, GCMG

- 1834: Sir Charles Colville, GCB, GCH

- 1835–1837: Gen. Hon. Sir Alexander Hope, GCB

- 1837–1862: Gen. Sir James Watson, KCB

- 1862–1870: Gen. Sir William Wood, KCB, KH

- 1870–1875: Gen. Maurice Barlow, CB

- 1875–1879: Gen. James Webber Smith, CB

The 14th (Buckinghamshire) Prince of Wales's Own Regiment

- 1879–1880: Gen. Sir Alfred Hastings Horsford, GCB

- 1880–1897: Gen. Alfred Thomas Heyland, CB

The Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment)

- 1897–1904: Gen. Sir Martin Andrew Dillon, GCB, CSI

- 1904–1914: Maj-Gen. William Hanbury Hawley

- 1914–1934: Maj-Gen. Sir William Fry, KCVO, CB

The West Yorkshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's Own)

- 1934–1947: F.M. Sir Cyril John Deverell, GCB, KBE

- 1947–1956: F.M. Sir William Joseph Slim, 1st Viscount Slim, KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC

- 1956–1958: Brig. Gerald Hilary Cree, CBE, DSO

References

- ↑ Cannon, p. 10

- ↑ Cannon, p. 17

- ↑ Cannon, p. 22

- ↑ Cannon, p. 26

- ↑ Cannon, p. 28

- ↑ Cannon, p. 29

- 1 2 3 4 "The West Yorkshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's Own)". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Cannon, p. 31

- ↑ Cannon, p. 32

- 1 2 Cannon, p. 34

- ↑ Knollenberg, pp. 76–78

- ↑ Guy, Louis L. jr. (2001). "Norfolk's Worst Nightmare". Norfolk Historical Society Courier. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ "Battle of Brandywine" (PDF). Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ "Major Patrick Ferguson, Inspector of Militia". Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Cannon, p. 40

- ↑ Cannon, p. 57

- ↑ Cannon, p. 68

- ↑ Cannon, p. 63

- ↑ Cannon, p. 65

- ↑ Cannon, p. 74

- ↑ "Regiments involved in the Second Anglo-Afghan War 1878–1880". Garen Ewing. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ "Training Depots 1873–1881". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 10 February 2006. Retrieved 16 October 2016. The depot was the 10th Brigade Depot from 1873 to 1881, and the 14th Regimental District depot thereafter

- ↑ "A History of Imphal Barracks" (PDF). Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ "No. 24992". The London Gazette. 1 July 1881. pp. 3300–3301.

- ↑ "No. 27214". The London Gazette. 27 July 1900. p. 4653.

- ↑ "No. 27356". The London Gazette. 17 September 1901. p. 6101.

- ↑ "The War – Embarcation of Troops". The Times (36070). London. 20 February 1900. p. 8.

- 1 2 3 "6th Battalion, The West Yorkshire Regiment". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 27 December 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Leeds Rifles". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 26 December 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907". Hansard. 31 March 1908. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "The West Yorkshire Regiment". The Long, Long Trail. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Prince of Wales's Own (West Yorkshire Regiment)". Orbat. Archived from the original on 16 October 2005. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "66 (Leeds Rifles)(W Yorks Rgt) Heavy AA Regt RA (TA)". Blue Yonder. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "49 (W Yorks Regt) Searchlight Regiment RA (TA)". Blue Yonder. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- 1 2 "45th (Leeds Rifles) Royal Tank Corps (TA)". Yorkshire Volunteers. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ "9th Indian Infantry Brigade". Orders of Battle. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Forty p. 51.

- ↑ "West Yorkshire Regiment". British Army units 1945 on. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ↑ Army List 1959

Sources

- Cannon, Richard (1845). Historical Record of the Fourteenth, or, the Buckinghamshire Regiment of Foot. London: Parker, Furnivall, and Parker.

- Forty, George (1998). British Army Handbook 1939–1945. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1403-3.

- Knollenberg, Bernhard (1975). Growth of the American Revolution, 1766–1775. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-02-917110-3. OCLC 1416300.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Yorkshire Regiment. |

- WYR's service with 62 Division in the Great War

- Bill Troughton's Webpage – featuring a book about his experiences in a Rangoon Prisoner of War camp

- Captain Dennis Parkin – Daily Telegraph obituary

- Yorkshire Volunteers website