The Way We Were

| The Way We Were | |

|---|---|

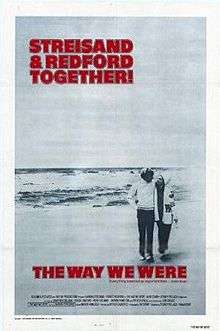

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold | |

| Directed by | Sydney Pollack |

| Produced by | Ray Stark |

| Written by | Arthur Laurents |

| Starring |

Barbra Streisand Robert Redford |

| Music by | Marvin Hamlisch |

| Cinematography | Harry Stradling, Jr. |

| Edited by |

John F. Burnett Margaret Booth (supervising) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 118 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $49 million[1] |

The Way We Were is a 1973 American romantic drama film starring Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford and directed by Sydney Pollack. The screenplay by Arthur Laurents was based on his college days at Cornell University and his experiences with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

A box office success, the film was nominated for several awards and won the Academy Award for Best Original Dramatic Score and Best Original Song for the theme song, "The Way We Were," It ranked at number 6 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions survey of the top 100 greatest love stories in American cinema. The Way We Were is considered one of the greatest romantic movies ever.[2][3][4][5][6][7] The soundtrack album became a gold record and hit the Top 20 on the Billboard 200 while the title song became a million-selling gold single, topping the Billboard Hot 100 respectively, selling more than two million copies. Billboard named "The Way We Were" as the number 1 pop hit of 1974. In 1998, the song was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame and finished at number 8 on AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs survey of top tunes in American cinema in 2004. It was also included in the list of Songs of the Century, by the Recording Industry Association of America and the National Endowment for the Arts.[8]

Plot

Told partly in flashback, it is the story of Katie Morosky (Barbra Streisand) and Hubbell Gardiner (Robert Redford). Their differences are immense: she is a stridently vocal Marxist Jew with strong anti-war opinions, and he is a carefree WASP with no particular political bent. While attending the same college, she is drawn to him because of his boyish good looks and his natural writing skill, which she finds captivating, although he does not work very hard at it. He is intrigued by her conviction and her determination to persuade others to take up social causes. Their attraction is evident, but neither of them acts upon it, and they lose touch after graduation.

The two meet again towards the end of World War II while Katie is working at a radio station, and Hubbell, having served as a naval officer in the South Pacific, is trying to return to civilian life. They fall in love despite the differences in their background and temperament. Soon, however, Katie is incensed by the cynical jokes Hubbell's friends make at the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and is unable to understand his indifference towards their insensitivity and shallow dismissal of political engagement. At the same time, his serenity is disturbed by her lack of social graces and her polarizing postures. Hubbell breaks it off with Katie, but soon agrees to work things out, at least for a time.

When Hubbell seeks a job as a Hollywood screenwriter, Katie believes he is wasting his talent and encourages him to pursue writing as a serious challenge instead. Despite her growing frustration, they move to California, where, without much effort, he becomes a successful screenwriter, and the couple enjoy an affluent lifestyle. As the Hollywood blacklist grows and McCarthyism begins to encroach on their lives, Katie's political activism resurfaces, jeopardizing Hubbell's position and reputation.

Alienated by Katie's persistent abrasiveness, Hubbell has a liaison with Carol Ann, his college girlfriend and the departing ex-wife of his best friend J.J., even though Katie is pregnant. After the birth, however, Katie and Hubbell decide to part when she finally understands he is not the man she idealized when she fell in love with him and will always choose the easiest way out, whether it is cheating in his marriage or writing predictable stories for sitcoms. Hubbell, on the other hand, is exhausted, unable to live on the pedestal Katie erected for him and face her disappointment in his decision to compromise his potential.

Katie and Hubbell meet by chance some years after their divorce, in front of the Plaza Hotel in New York City. Hubbell, who is with a stylish beauty and apparently content, is now writing for a popular sitcom as one of a group of nameless writers. Katie, now remarried, invites Hubbell to come for a drink with his lady friend, but he confesses he cannot. He does inquire how their daughter Rachel is doing, just to ascertain that Katie's new husband is a good father, but shows no intention to meet her.

Katie has remained faithful to who she is: flyers in hand, she is agitating for the newest political causes. Their past is behind them and all the two share now (besides their daughter, Rachel) is a missing sensation and the memory of the way they were.

Cast

- Barbra Streisand as Katie Morosky

- Robert Redford as Hubbell Gardiner

- Bradford Dillman as J.J.

- Lois Chiles as Carol Ann

- Patrick O'Neal as George Bissinger

- Viveca Lindfors as Paula Reisner

- Allyn Ann McLerie as Rhea Edwards

- Murray Hamilton as Brooks Carpenter

- Herb Edelman as Bill Verso

- Diana Ewing as Vicki Bissinger

- Sally Kirkland as Pony Dunbar

- George Gaynes as El Morocco Captain

- James Woods as Frankie McVeigh

- Susan Blakely as Judianne

Production

In 1937, while an undergraduate at Cornell, Arthur Laurents was introduced to political activism by a student who became the model for Katie Morosky, a member of the Young Communist League and an outspoken opponent of Francisco Franco and his effort to take control of Spain via the Spanish Civil War. The fiery campus radical organized rallies and a peace strike, and the memory of her fervor remained with Laurents long after the two lost touch.

Laurents decided to develop a story with a similar character at its center, but was unsure what other elements to add. He recalled a creative writing instructor named Robert E. Short, who felt he had a good ear for dialogue and had encouraged him to write plays. His first instinct was to create a crisis between his leading lady and her college professor, but he decided her passion needed to be politics, not writing. What evolved was a male character who had a way with words but no strong inclination to apply himself to a career using them.[9]

Because of his own background, Laurents felt it was important for his heroine to be Jewish and share his outrage at injustice. He also thought it was time a mainstream Hollywood film had a Jewish heroine, and because Barbra Streisand was the industry's most notable Jewish star, he wrote the role of Katie Morosky for her. Laurents had already known Streisand for some time, having cast her in his 1962 Broadway musical I Can Get it For You Wholesale. Hubbell Gardiner, initially a secondary character, was drawn from several people Laurents knew. The first name was borrowed from urbane television producer Hubbell Robinson, who had hired Laurents to write an episode of ABC Stage 67. The looks and personality came from two primary sources: writer Peter Viertel and a man Laurents referred to only as "Tony Blue Eyes," an acquaintance who inspired the scene where the creative writing instructor reads Hubbell's short story to his class.[10]

Laurents wrote a lengthy treatment for Ray Stark, who read it on a transcontinental flight and called the screenwriter the moment he arrived in Los Angeles to greenlight the project. Laurents had been impressed with They Shoot Horses, Don't They? and suggested Sydney Pollack direct. Streisand was impressed that he had studied with Sanford Meisner at the Neighborhood Playhouse in Manhattan and seconded the choice. Stark was less enthused, but agreed because Pollack assured him he could deliver Robert Redford for the role of Hubbell, which Laurents had written with Ryan O'Neal in mind. O'Neal's affair with Streisand was at its end, and Stark wanted to avoid conflicts between the leads.[11]

Laurents ultimately regretted recommending Pollack. The director demanded the role of Hubbell be made equal to that of Katie, and throughout filming, for unexplained reasons, he kept Laurents away from Redford. What was intended to be the final draft of the screenplay was written by Laurents and Pollack at Stark's condominium in Sun Valley, Idaho. Laurents, dismayed to discover very little of his work remained when it was completed, left the project. Over time eleven writers, including Dalton Trumbo, Alvin Sargent, Paddy Chayefsky, and Herb Gardner, contributed to the script. The end result was a garbled story filled with holes that neither Streisand nor Redford liked. Laurents was asked to return and did so only after demanding and receiving an exorbitant amount of money.[12]

Because the film's start date was delayed while it underwent numerous rewrites, Cornell was lost as a shooting location. Union College in Schenectady, New York, was used instead. Other locations included the village of Ballston Spa in upstate New York, Central Park, the beach in Malibu, and Union Station in Los Angeles, the latter for a scene Laurents felt was absurd and fought to have deleted, without success.[13]

Laurents was horrified when he saw the first rough cut of the film. He thought there were a few good scenes, and some good moments in bad scenes, but overall he thought it was a badly photographed jumbled mess lacking coherence. Both stars appeared to be playing themselves more often than their characters, and Streisand often used a grand accent that Laurents felt hurt her performance. Pollack admitted the film was not good, accepted full responsibility for its problems, and apologized for his behavior. The following day he retreated to the editing room to improve it as much as possible. Laurents felt the changes made it better but never as good as it could have been.[14]

A decade after the film was released, Redford, having made peace with Laurents, contacted him to discuss the possibility of collaborating on a new project, and eventually the two settled on a sequel to The Way We Were. In it, Hubbell and his daughter, a radical like Katie, would meet but be unaware of their relationship, and complications would ensue. Both agreed they did not want Pollack to be part of the equation. Laurents sent Redford the completed script but, aside from receiving a brief note acknowledging the actor had received it and looked forward to reading it, he never heard from him again. In 1982, Pollack approached Laurents about a sequel Stark had proposed, but nothing transpired following their initial discussion. In 1996, Streisand came across the sequel Laurents had written, and decided she wanted to produce and direct it as well as co-star with Redford, but did not want to work with Stark. Laurents thought the script was not as good as he remembered it being, and agreed to rewrite it once Stark agreed to sell the rights to the characters and their story to Streisand. Again, nothing happened. The following year, Stark asked Laurents if he was interested in adapting the original film for a stage musical starring Kathie Lee Gifford. Laurents declined, and any new projects related to the film have been in limbo ever since.[15]

Soundtrack

The musical score for The Way We Were was composed by Marvin Hamlisch. A soundtrack album was released in January 1974 to much success. At the time of its initial release, the album peaked at #20 on the Billboard 200. On October 19, 1993, it was re-released on compact disc by Sony. It includes Streisand's rendition of "The Way We Were", which at the time of the film's release was a commercial success and her first #1 single in the United States. It entered the Billboard Hot 100 in November 1973 and charted for 23 weeks, eventually selling over a million copies and remaining #1 for three non-consecutive weeks in February 1974. On the Adult Contemporary chart, it was Streisand's second #1 hit, following "People" a decade earlier. It was the title track of a Streisand album that also reached #1.

Reception

In North America, the movie was a massive commercial success, grossing $49,919,870.[16] It became the 5th highest-grossing film of the year, The film earned an estimated $10 million in North American rentals in 1973,[17] and a total of $22,457,000 in its theatrical run.

Critical response

The Way We Were was featured on the Top Ten Films of 1973 by National Board of Review. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called the film "essentially just a love story, and not sturdy enough to carry the burden of both radical politics and a bittersweet ending." He added, "It's easy to forgive the movie a lot because of Streisand. She's fantastic. She's the brightest, quickest female in movies today, inhabiting her characters with a fierce energy and yet able to be touchingly vulnerable . . . The Redford character perhaps in reaction to the inevitable Streisand performance, is passive and without edges. The primary purpose of the character is to provide someone into whose life Streisand can enter and then leave. That's sort of thankless, but Redford handles it well." [18] Conversely, TV Guide awarded the film three out of four stars, calling it "an engrossing, if occasionally ludicrous, hit tearjerker" and "a great campy romance."[19]

In her review, Pauline Kael noted that "the decisive change in the characters' lives which the story hinges on takes place suddenly and hardly makes sense." She was not the only critic to question the gap in the plot; of the scene in the hospital shortly after Katie gives birth and they part indefinitely, Molly Haskell wrote, "She seems to know all about it, but it came as a complete shock to me."[20] The sloppy editing was exposed in other ways as well; in his review, critic John Simon wrote: "Some things, I suppose, never change, like the necktie Redford wears in two scenes that take place many years apart."

Variety called it "a distended, talky, redundant and moody melodrama" and added, "The overemphasis on Streisand makes the film just another one of those Streisand vehicles where no other elements ever get a chance."[21] Time Out London observed, "[W]ith the script glossing whole areas of confrontation (from the Communist '30s to the McCarthy witch-hunts), it often passes into the haze of a nostalgic fashion parade. Although Streisand's liberated Jewish lady is implausible, and emphasizes the period setting as just so much dressing, Redford's Fitzgerald-type character . . . is an intriguing trailer for his later Great Gatsby. It's a performance that brings more weight to the film than it deserves, often hinting at depths that are finally skated over."[22]

Awards and nominations

Wins

- Best Music (Original Dramatic Score) Marvin Hamlisch

- Best Music (Song) Marvin Hamlisch, Alan Bergman, and Marilyn Bergman for "The Way We Were"

Nominations

- Best Actress in a Leading Role Barbra Streisand

- Best Art Direction Stephen B. Grimes and William Kiernan

- Best Cinematography Harry Stradling Jr.

- Best Costume Design Dorothy Jeakins and Moss Mabry

- ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards

- ASCAP Awards Most Performed Feature Film Standards on TV (Marvin Hamlisch, Alan Bergman, and Marilyn Bergman for "The Way We Were," winner)

- BAFTA Awards

- Best Actress in a Leading Role (Barbra Streisand, nominee)

- David di Donatello Awards

- Best Foreign Actress (Barbra Streisand, winner; tie with Tatum O'Neal for Paper Moon)[24]

- Golden Globes

- Best Original Song (Marvin Hamlisch, Alan Bergman, and Marilyn Bergman for "The Way We Were," winner)

- Best Actress - Motion Picture Drama (Barbra Streisand, nominee)

- Grammy Awards

- International Film Festival of India

- International Film Festival of India Silver Peacock Award for Best Actress(winner)

- National Board of Review

- National Board of Review: Top Ten Films of 1973(winner)[26]

- Writers Guild of America Awards

- Best Original Screenplay (Arthur Laurents, nominee)

In popular culture

In Gilda Radner's concert movie Gilda Live, her character Lisa Loopner performs "The Way We Were" on the piano. Loopner says of the movie, "It's about a Jewish woman with a big nose and her blond boyfriend who move to Hollywood, and it's during the blacklist and it puts a strain on their relationship."

The Simpsons had two episodes, one called "The Way We Was" (first aired in 1991) and the other "The Way We Weren't" (first aired in 2004), although their plots are unrelated to the movie.

In his autobiography If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor, cult star Bruce Campbell recalls a roommate who had a poorly functioning record player. Campbell writes, "A tinny 'The Way We Were' kept me awake."

In Season Five Episode 14 of Gilmore Girls, Lorelai calls Luke after they've broken up and tells him that she was thinking about The Way We Were and reminded him of how Katie called Hubbell after they'd broken up and asked him to come sit with her because he was her best friend and she needed her best friend.

In Season One Episode 20 of That '70s Show, Kitty Forman says that The Way We Were was a nice movie, after Eric explains a scene in Star Wars.

In Season Two Episode 18 of Sex and the City, Carrie uses The Way We Were as an analogy for her relationship with Big. The girls proceed to sing the film's theme song, and later, when Carrie bumps into Big outside his engagement party, she quotes a line from the film.

See also

References

- ↑ "The Way We Were (1973)". The Numbers. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ "The 25 All-Time Greatest Movies About Love". www.vanityfair.com. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ↑ "23 Reasons "The Way We Were" Featured The Best Romance Of All Time". buzzfeed.com. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ↑ "The 100 best romantic movies". www.timeout.com. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ↑ "List of the Most Romantic Movies of all Time". www.franksreelreviews.com. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ↑ "The 50 Best Romantic Movies". whatsontv.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ↑ "Top 100 Best Romance Movies Of All Time". whatsontv.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ↑ "Songs of the Century". cnn.com. CNN. 7 March 2001. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Laurents, Arthur, Original Story By. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000. ISBN 0-375-40055-9, pp. 254-57

- ↑ Laurents, pp. 258-63

- ↑ Laurents, p. 266

- ↑ Laurents, pp. 267-74

- ↑ Laurents, pp. 277-79

- ↑ Laurents, pp. 280-81

- ↑ Laurents, pp. 283-85

- ↑ "The Way We Were (1973)". The Numbers. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Big Rental Films of 1973", Variety, 9 January 1974 p 19

- ↑ Roger Ebert (17 October 1973). "The Way We Were". Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "The Way We Were". TVGuide.com. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ Laurents, pp. 281-82

- ↑ Variety Staff. "The Way We Were". Variety. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "The Way We Were". Time Out London. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Oscars.org -- The Way We Were". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ↑ "Come eravamo (The Way We Were)". mymovies.it. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ↑ "1974 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ↑ Barbra Streisand. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Way We Were |

- The Way We Were on IMDb

- The Way We Were at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Way We Were at the TCM Movie Database

- McCarthyism and the Movies

- Barbra Archives: The Way We Were cut scenes and song demos