Throne

A throne is the seat of state of a potentate or dignitary, especially the seat occupied by a sovereign on state occasions; or the seat occupied by a pope or bishop on ceremonial occasions.[1] "Throne" in an abstract sense can also refer to the monarchy or the Crown itself, an instance of metonymy, and is also used in many expressions such as "the power behind the throne".

When used in a political or governmental sense, throne typically refers to a civilization, nation, tribe, or other politically designated group that is organized or governed under an authoritarian system. Throughout much of human history societies have been governed under authoritarian systems, in particular dictatorial or autocratic systems, resulting in a wide variety of thrones that have been used by given heads of state. These have ranged from stools in places such as a Africa to ornate chairs and bench-like designs in Europe and Asia, respectively. Often, but not always, a throne is tied to a philosophical or religious ideology held by the nation or people in question, which serves a dual role in unifying the people under the reigning monarch and connecting the monarch upon the throne to his or her predecessors, who sat upon the throne previously. Accordingly, many thrones are typically held to have been constructed or fabricated out of rare or hard to find materials that may be valuable or important to the land in question. Depending on the size of the throne in question it may be large and ornately designed as an emplaced instrument of a nation's power, or it may be symbolic chair with little or no precious materials incorporated into the design.

When used in a religious sense, throne can refer to one of two distinct uses. The first use derives from the practice in churches of having a bishop or higher-ranking religious official (archbishop, Pope, etc.) sit on a special chair which in church referred to by written sources as a "throne", and is intended to allow such high-ranking religious officials a place to sit in their place of worship. The other use for throne refers to a belief among many of the world's monotheistic and polytheistic religions that the deity or deities that they worship are seated on a throne. Such beliefs go back to ancient times, and can be seen in surviving artwork and texts which discuss the idea of ancient gods (such as the Twelve Olympians) seated on thrones. In the major Abrahamic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, the Throne of God is attested to in religious scriptures and teachings, although the origin, nature, and idea of the Throne of God in these religions differs according to the given religious ideology practiced.

In the west, a throne is most identified as the seat upon which a person holding the title King, Queen, Emperor, or Empress sits in a nation using a monarchy political system, although there are a few exceptions, notably with regards to religious officials such as the Pope and bishops of various sects of the Christian faith. Changing geo-political tides have resulted in the collapse of several dictatorial and autocratic governments, which in turn have left a number of throne chairs empty, however the significance of a throne chair is such that many of these thrones - such as China's Dragon Throne - survive today as historic examples of nation's previous government.

Antiquity

Thrones were found throughout the canon of ancient furniture. The depiction of monarchs and deities as seated on chairs is a common topos in the iconography of the Ancient Near East.

The word throne itself is from Greek θρόνος (thronos), "seat, chair",[2] in origin a derivation from the PIE root *dher- "to support" (also in dharma "post, sacrificial pole"). Early Greek Διὸς θρόνους (Dios thronous)[3] was a term for the "support of the heavens", i.e. the axis mundi, which term when Zeus became an anthropomorphic god was imagined as the "seat of Zeus".[4] In Ancient Greek, a "thronos" was a specific but ordinary type of chair with a footstool, a high status object but not necessarily with any connotations of power. The Achaeans (according to Homer) were known to place additional, empty thrones in the royal palaces and temples so that the gods could be seated when they wished to be. The most famous of these thrones was the throne of Apollo in Amyclae.

The Romans also had two types of thrones- one for the Emperor and one for the goddess Roma whose statues were seated upon thrones, which became centers of worship.

Hebrew Bible

The word "throne" in English translations of the Bible renders Hebrew כסא kissē'. The Pharaoh of the Exodus is described as sitting on a throne (Exodus 11:5, 12:29), but mostly the term refers to the throne of the kingdom of Israel, often called the "throne of David" or "throne of Solomon". The literal throne of Solomon is described in 1 Kings 10:18-20: "Moreover the king made a great throne of ivory, and overlaid it with the best gold.. The throne had six steps, and the top of the throne was round behind: and there were stays on either side on the place of the seat, and two lions stood beside the stays. And twelve lions stood there on the one side and on the other upon the six steps: there was not the like made in any kingdom." In the Book of Esther (5:3), the same word refers to the throne of the king of Persia.

The god of Israel himself is frequently described as sitting on a throne, referred to outside of the Bible as the Throne of God, in the Psalms, and in a vision Isaiah (6:1), and notably in Isaiah 66:1, YHWH says of himself "The heaven is my throne, and the earth is my footstool" (this verse is alluded to by Matthew 5:34-35).

Christianity

Christian Bible

In the New Testament, the angel Gabriel also refers to this throne in the Gospel of Luke (1:32-33): "He will be great, and will be called the Son of the Highest; and the Lord God will give Him the throne of His father David. And He will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of His kingdom there will be no end."

Jesus promised his Apostles that they would sit upon "twelve thrones", judging the twelve tribes of Israel (Matthew 19:28). John's Revelation states: "And I saw a great white throne, and him that sat on it, from whose face the earth and the heaven fled away" (Revelation 20:11).

The Apostle Paul speaks of "thrones" in Colossians 1:16. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, in his work, De Coelesti Hierarchia (VI.7) interprets this as referring to one of the ranks of angels (corresponding to the Hebrew Arelim or Ophanim). This concept was expanded upon by Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologica (I.108), wherein the thrones are concerned with carrying out divine justice.

In Medieval times the "Throne of Solomon" was associated with the Virgin Mary, who was depicted as the throne upon which Jesus sat. The ivory in the biblical description of the Throne of Solomon was interpreted as representing purity, the gold representing divinity, and the six steps of the throne stood for the six virtues. Psalm 45:9 was also interpreted as referring to the Virgin Mary, the entire Psalm describing a royal throne room.

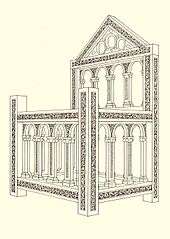

Ecclesiastical thrones

From ancient times, bishops of the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican and other churches where episcopal offices exist, have been formally seated on a throne, called a cathedra (Greek: κάθεδρα, seat). Traditionally located in the sanctuary, the cathedra symbolizes the bishop's authority to teach the faith (hence the expression "ex cathedra") and to govern his flock.

"Ex cathedra" refers to the explicative authority, notably the extremely rarely used procedure required for a papal declaration to be 'infallible' under Roman Catholic Canon law. In several languages the word deriving from cathedra is commonly used for an academic teaching mandate, the professorial chair.

From the presence of this cathedra (throne), which can be as elaborate and precious as fits a secular prince (even if the prelate is not a prince of the church in the secular sense), a bishop's primary church is called a cathedral. In the Roman Catholic Church, a basilica -from the Greek basilikos 'royal'-, now refers to the presence there of a papal canopy (ombrellino), part of his regalia, and applies mainly to many cathedrals and Catholic churches of similar importance and/or splendor. In Roman Antiquity a basilica was secular public hall. Thus, the term basilica may also refer to a church designed after the manner of the ancient Roman basilica. Many of the churches built by the emperor Constantine the Great and Justinian are of the basilica style.

Some other prelates besides bishops are permitted the use of thrones, such as abbots and abbesses. These are often simpler than the thrones used by bishops and there may be restrictions on the style and ornamentation used on them, according to the regulations and traditions of the particular denomination.

As a mark of distinction, Roman Catholic bishops and higher prelates have a right to a canopy above their thrones at certain ecclesiastical functions. It is sometimes granted by special privilege to prelates inferior to bishops, but always with limitations as to the days on which it may be used and the character of its ornamentation. The liturgical color of the canopy should correspond with that of the other vestments. When ruling monarchs attend services, they are also allowed to be seated on a throne that is covered by a canopy, but their seats must be outside the sanctuary.[5]

In the Greek Orthodox Church, the bishop's throne will often combine features of the monastic choir stall (kathisma) with appurtenances inherited from the Byzantine court, such as a pair of lions seated at the foot of the throne.

The term "throne" is often used in reference to Patriarchs to designate their ecclesiastical authority; for instance, "the Ecumenical Throne" refers to the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.

Western bishops may also use a faldstool to fulfill the liturgical purpose of the cathedra when not in their own cathedral.

Papal Thrones

In the Roman Catholic Church, the Pope is an elected monarch, both under canon law as supreme head of the church, and under international law as the head of state -styled "sovereign pontiff"- of the Vatican City State (the sovereign state within the city of Rome established by the 1929 Lateran Treaty). Until 1870, the Pope was the elected monarch of the Papal States, which for centuries constituted one of the largest political powers on the divided Italian peninsula. To this day, the Holy See maintains officially-recognised diplomatic status, and papal nuncios and legates are deputed on diplomatic missions throughout the world.

The Pope's throne (Cathedra Romana), is located in the apse of the Archbasilica of St. John Lateran, his cathedral as Bishop of Rome.

In apse of Saint Peter's Basilica, above the "Altar of the Chair" lies the Cathedra Petri, a throne believed to have been used by St Peter himself and other earlier Popes; this relic is enclosed in a gilt bronze casting and forms part of a huge monument designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Unlike at his cathedral, there is no permanent cathedra for the Pope in St Peter's Basilica, so a removable throne is placed in the Basilica for the Pope's use whenever he presides over a liturgical ceremony. Prior to the liturgical reforms that occurred in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, a huge removable canopied throne was placed above an equally removable dais in the choir side of the "Altar of the Confession" (the high altar above the tomb of St Peter and beneath the monumental bronze baldachin); this throne stood between the apse and the Altar of the Confession.

This practice has fallen out of use with the 1960s and 1970s reform of Papal liturgy and, whenever the Pope celebrates Mass in St. Peter's Basilica, a simpler portable throne is now placed on platform in front of the Altar of the Confession. However, whenever Pope Benedict XVI celebrated the Liturgy of the Hours at St Peter's, a more elaborate removable throne was placed on a dais to the side of the Altar of the Chair. When the Pope celebrates Mass on the Basilica steps facing St. Peter's Square, portable thrones are also used.

In the past, the pope was also carried on occasions in a portable throne, called the sedia gestatoria. Originally, the sedia was used as part of the elaborate procession surrounding papal ceremonies that was believed to be the most direct heir of pharaonic splendor, and included a pair of flabella (fans made from ostrich feathers) to either side. Pope John Paul I at first abandoned the use of these implements, but later in his brief reign began to use the sedia so that he could be seen more easily by the crowds. However, he did not restore the use of the flabella. The use of the sedia was abandoned by Pope John Paul II in favor of the so-called "popemobile" when outside. Near the end of his pontificate, Pope John Paul II had a specially-constructed throne on wheels that could be used inside.

Prior to 1978, at the Papal conclave, each cardinal was seated on a throne in the Sistine Chapel during the balloting. Each throne had a canopy over it. After a successful election, once the new pope accepted election and decided by what name he would be known, the cardinals would all lower their canopies, leaving only the canopy over the newly elected pope. This was the new pope's first throne. This tradition was dramatically portrayed in the 1963 film, The Shoes of the Fisherman.

Islam

Middle Ages

In European feudal countries, monarchs often were seated on thrones, based in all likelihood on the Roman magisterial chair. These thrones were originally quite simple, especially when compared to their Asian counterparts. One of the grandest and most important was the Throne of Ivan "the Terrible". Dating from the mid-16th century, it is shaped as a high-backed chair with arm rests, and adorned with ivory and walrus bone plaques intricately carved with mythological, heraldic and life scenes. The plaques carved with scenes from the biblical account of King David’s life are of particular relevance, as David was seen as the ideal for Christian monarchs.[6]

The throne of the Byzantine Empire (Magnaura) included elaborate automatons of singing birds.[7]

In the 'regency' (nominally an Ottoman province, de facto an independent realm) of the Bey of Tunis, the throne was called kursi.

South Asia

In the Indian subcontinent, the traditional Sanskrit name for the throne was singhāsana (lit., seat of a lion). In the Mughal times the throne was called Shāhī takht ([ˈʃaːhiː ˈtəxt]). The term gaddi (Hindustani pronunciation: [ˈɡəd̪d̪i], also called rājgaddī) referred to a seat with a cushion used as a throne by Indian princes.[8] The term gaddi was usually used for the throne of a Hindu princely state's ruler, while among Muslim princes or Nawabs, save exceptions such as the Travancore State royal family,[9] the term musnad ([ˈməsnəd]), also spelt as musnud, was more common, even though both seats were similar.

The Throne of Jahangir was built by Mughal emperor Jahangir in 1602 and is located at the Diwan-i-Khas (hall of private audience) at the Agra Fort.

The Peacock Throne was the seat of the Mughal emperors of India. It was commissioned in the early 17th century by emperor Shah Jahan and was located in the Red Fort of Delhi. The original throne was subsequently captured and taken as a war trophy in 1739 by the Persian king Nadir Shah, and has been lost ever since. A replacement throne based on the original was commissioned afterwards and existed until the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Maharaja Ranjit Singh's throne was made by the goldsmith Hafez Muhammad Multani about 1820 to 1830. Made of Wood and resin core, covered with sheets of repoussé, chased and engraved gold.[10]

The Golden Throne or Chinnada Simhasana or Ratna Simahasana in Kannada is the royal seat of the rulers of the Kingdom of Mysore. The Golden throne is kept at Mysore Palace.

East Asia

The Dragon Throne is the term used to identify the throne of the Emperor of China. As the dragon was the emblem of divine imperial power, the throne of the emperor, who was considered a living god, was known as the Dragon Throne.[11] The term can refer to very specific seating, as in the special seating in various structures in the Forbidden City of Beijing or in the palaces of the Old Summer Palace. In an abstract sense, the "Dragon Throne" also refers rhetorically to the head of state and to the monarchy itself.[12] The Daoguang Emperor is said to have referred to his throne as "the divine utensil."

Dragon Throne Vietnam of the Emperors of Vietnam

The Phoenix Throne (어좌 eojwa) is the term used to identify the throne of the King of Korea. In an abstract sense, the Phoenix Throne also refers rhetorically to the head of state of the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897) and the Empire of Korea (1897–1910). The throne is located at Gyeongbok Palace in Seoul.

The Chrysanthemum Throne (皇位 kōi, lit. "Imperial position/rank") is the term used to identify the throne of the Emperor of Japan. The term also can refer to very specific seating, such as the takamikura (高御座) throne in the Shishin-den at Kyoto Imperial Palace.[13]

The throne of the Ryukyu Kingdom is located in Shuri Castle, Naha.

Modern period

During the Russian Empire, the throne in St. George's Hall (the "Greater Throne Room") in the Winter Palace was regarded as the throne of Russia. It sits atop a seven-stepped dais with a proscenium arch above and the symbol of the Imperial Family behind (the two-headed eagle). Peter I's Room (the "Smaller Throne Room") is modest in comparison to the former. The throne was made for Empress Anna Ivanovna in London. There is also a throne in the Grand Throne Room of the Peterhof Palace.

In some countries with a monarchy, thrones are still used and have important symbolic and ceremonial meaning. Among the most famous thrones still in usage are St Edward's Chair, on which the British monarch is crowned, and the thrones used by monarchs during the state opening of parliaments in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and Japan (see above) among others.

Some republics use distinctive throne-like chairs in some state ceremonial. The President of Ireland sits on a former viceregal throne during his or her inauguration ceremony while Lords Mayor of many British and Irish cities often preside over local councils from throne-like chairs.

List of named thrones

Europe

- The Throne of Apollo in Amyclae

- St. Edward's Chair in Westminster Abbey, London, where British monarchs are crowned. It at one time contained the Stone of Scone (also called the Stone of Destiny) upon which the Kings of Scotland were crowned

- The Throne of Charlemagne in the cathedral at Aachen, Germany

- The Imperial Throne of the medieval German kings and emperors in Goslar, Germany.

- The Throne of the King of Aragon, Valencia, Majorca, Sardinia, Corsica and Sicilia and Count of Barcelona Martin I the Elder.

- The Ivory Throne of Ivan the Terrible

- The papal sedia gestatoria

- Throne Chair of Denmark

- Queen Christina's Silver Throne in the Royal Palace, Stockholm, Sweden.

Africa

- the Golden throne of pharaoh Tutankhamun

- the Golden Stool of the Ashanti

- the Throne of David of the Emperors of Ethiopia

- the Chieftaincy Stools of Nigeria

Asia

- Dragon Throne of the Emperors of China

- Dragon Throne Vietnam of the Emperors of Vietnam

- Chrysanthemum Throne of the Emperors of Japan (ja:高御座)

- the Phoenix Throne of the Kings of Korea

- the Lion Throne of the Dalai Lama of Tibet

- the Lion Throne of Sikkim

- the Stone throne of King Kasyapa from Sri Lanka from the 5th century citadel of Sigiri

- the Stone throne of King Nissankamalla from Sri Lanka from the 12th century Polonnaruwa kingdom

- the Kandian Throne of the Kingdom of Kandy and the Dominion of Ceylon

- the Peacock Throne of the Mughal Emperors of India

- the Marble Throne and Sun Throne of the Persian Shahs

- the Peacock Throne of Korea

- the Peacock Throne at Montchobo, then at Ava, ancient capitals of Burma

- the Saridhaleys "ivory throne" and the sighsana "lion throne" of the Maldives sultanate

- the Sandalwood throne at Bikaner Fort

- Maharaja Ranjit Singh's throne

Image gallery

Queen Christina's Silver Throne, the Royal Throne of Sweden

Queen Christina's Silver Throne, the Royal Throne of Sweden

Throne of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

Throne of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria

.jpg) Imperial throne of Catherine the Great

Imperial throne of Catherine the Great Throne of Emperor Napoleon I, dating from 1808, in the throne room at the Palace of Fontainebleau

Throne of Emperor Napoleon I, dating from 1808, in the throne room at the Palace of Fontainebleau

Throne of the Emperor of Brazil, Pedro I

Throne of the Emperor of Brazil, Pedro I_Room_1863.jpg) Imperial throne of Peter I The Great

Imperial throne of Peter I The Great

Thrones of the king and queen of Spain, Madrid

Thrones of the king and queen of Spain, Madrid- Throne of Polish King Stanisław II Augustus at Warsaw Royal Castle

Throne of the monarch of the Netherlands in the Ridderzaal

Throne of the monarch of the Netherlands in the Ridderzaal Imperial throne used for the Enthronement of the Japanese Emperor

Imperial throne used for the Enthronement of the Japanese Emperor- Throne of the pope, Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, Rome

Throne of the pope, Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, Rome

Throne of the pope, Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, Rome- Throne of Pope Honorius III

Throne of Pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini)

Throne of Pope Pius II (Enea Silvio Piccolomini)

See also

Other uses

- In music, the stool used to sit behind a drum kit is often called a throne.

- In religion, a niche in an altar piece for displaying the Holy Sacrament is called a throne.

- In slang, a common sit-down toilet is also called a throne, or more formally the 'porcelain throne'.

- One of the Angel choirs is an order called Ophanim or 'Thrones', said to carry God's heavenly throne — other choir names expressing power in secular terms include Powers, Principalities, Dominions

Sources and references

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, ISBN 0-19-861186-2

- ↑ θρόνος, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ↑ Sophocles, Antigone, 1041, on Perseus

- ↑ Janda, Michael, Die Musik nach dem Chaos, Innsbruck 2010.

- ↑ "Canopy". The Catholic Encyclopedia. III. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1908. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ↑ "Throne of Ivan IV the Terrible". Regalia of Russian Tsars. The Moscow Kremlin. Retrieved 2007-07-12.

- ↑ Brett, Gerard (July 1954). "The Automata in the Byzantine "Throne of Solomon"". Speculum. 29 (3): 477–487. ISSN 0038-7134. JSTOR 2846790. doi:10.2307/2846790.

- ↑ Mark Brentnall, ed. The Princely and Noble Families of the Former Indian Empire: Himachal Pradesh pg. 301

- ↑ Velu Pillai. Travancore State Manual (1940)

- ↑ http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-court-of-maharaja-ranjit-singh/

- ↑ Arnold, Julean Herbert. (1920). Commercial Handbook of China, p. 446.

- ↑ Williams, David. (1858). The preceptor's assistant, or, Miscellaneous questions in general history, literature, and science, p. 153.

- ↑ Ponsonby-Fane, Richard. (1959). The Imperial House of Japan, p. 337.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thrones. |

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Throne |

| Look up throne in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

.png)