The Thrill Book

The Thrill Book was a U.S. pulp magazine published by Street & Smith in 1919. It was intended to carry "different" stories: this meant stories that were unusual or unclassifiable, which in practice often meant that the stories were fantasy or science fiction. The first eight issues, edited by Harold Hersey, were a mixture of adventure and weird stories. Contributors included Greye La Spina, Charles Fulton Oursler, J. H. Coryell, and Seabury Quinn. Hersey was replaced by Ronald Oliphant with the July 1 issue, probably because Street & Smith were unhappy with his performance.

Oliphant printed more science fiction and fantasy than Hersey had done, though this included two stories by Murray Leinster which Hersey had purchased before being replaced. The most famous story from The Thrill Book is The Heads of Cerberus, a very early example of a novel about alternate time tracks, by Francis Stevens. Oliphant was given a larger budget than Hersey, and was able to acquire material by popular writers such as H. Bedford-Jones, but he was only able to produce eight more issues before the end came. The last issue was dated October 15, 1919; it was probably cancelled because of poor sales, although a printers' strike at that time may have been a factor.

Although The Thrill Book has been described as the first American pulp to specialize in fantasy and science fiction, this description is not supported by recent historians of the field, who regard it instead as a stepping stone on the path that ultimately led to Weird Tales and Amazing Stories, the first true specialized magazines in the fields of weird fiction and science fiction respectively.

Publication history

In the late 19th century popular magazines typically did not print fiction to the exclusion of other content; they would include non-fiction articles and poetry as well. In October 1896, the Frank A. Munsey company's Argosy magazine was the first to switch to printing only fiction, and in December of that year it switched to using cheap wood-pulp paper. This is now regarded by magazine historians as having been the start of the pulp magazine era.[3] For twenty years pulp magazines were successful without restricting their fiction content to any specific genre, but in 1915 the influential magazine publisher Street & Smith began to issue titles that focused on a particular niche, such as Detective Story Magazine and Western Story Magazine, thus pioneering the specialized and single-genre pulps.[3][4] In the midst of these changes, some time in 1918, Street & Smith's circulation manager, Henry Ralston, decided to launch a new magazine to publish "different" stories: "different" meant stories that were unusual or unclassifiable in some way, which in most cases meant that they included either fantasy or science fiction elements.[4][5][note 1] In The Fiction Factory, Quentin Reynolds' history of Street & Smith, Reynolds asserts that the magazine was the brainchild of Ormond G. Smith, one of the publishers, but pulp historian Will Murray regards this as unlikely to be the full story, given that Reynolds' book was written almost forty years later and was an "approved" history. Murray asserts that Ralston was certainly involved in the creation of The Thrill Book.[6] Walter Adolphe Roberts, the editor of Street & Smith's Ainslee's Magazine, told a friend of his, Harold Hersey, that Ralston was looking for an editor for a new magazine.[4] Hersey had sold some writing to the pulps but his editorial experience was limited to no more than a year's work on several little magazines.[7] He met with Ralston in early 1919 and was immediately hired on the basis of the interview. It is possible that Eugene A. Clancy, the editor of Street & Smith's The Popular Magazine, was originally intended to be the editor of The Thrill Book, but was unable to take on the additional work, though Clancy did assist Hersey on some issues of The Thrill Book.[8] Bringing Hersey on as editor was unfortunate; historians of the field describe Hersey as lacking talent both as a writer and an editor.[9][10][11][12]

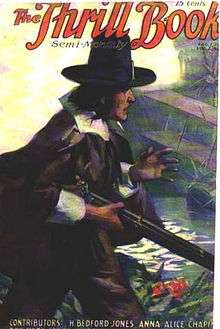

The first issue of The Thrill Book was dated March 1, 1919, and was published in a format similar to that of a dime novel.[13] The choice of format was probably a mistake, as it was associated in the minds of the buying public with low-quality fiction aimed at readers with very low standards.[14] The plan to publish twice a month indicated that Street & Smith were confident that the new magazine would be successful.[15]

With the ninth issue, dated July 1, 1919, Hersey was replaced by Ronald Oliphant.[16] The reason he was replaced is not clear, though several explanations have been suggested. Murray Leinster claimed that Hersey was fired for publishing too much of his own fiction and poetry in the magazine; according to Leinster, some of the poetry may have actually been written by Hersey's mother rather than by Hersey himself.[16][17] Pulp historian Richard Bleiler regards this theory as unlikely, since although up to eighteen of the twenty-five short poems in the first eight issues of the magazine may have been by Hersey, only two stories in those issues are definitely by him, and there are only four other stories which may have been Hersey's work published under a pseudonym. Bleiler suggests that at most Street & Smith would have reprimanded Hersey, and that the real reason for his dismissal is more likely to be that Street & Smith were dissatisfied with The Thrill Book under his editorship. Bleiler also suggests that Hersey may have started the rumor that he was let go for buying too much of his own material, as this would have been less harmful to his reputation than a dismissal for failure.[18] Hersey himself claimed that he was not fired, but quit: "I wasn't fired, but I should have been ... I saw the 'handwriting on the wall' ahead of time. I asked to be relieved of my duties ... and my request was promptly accepted!"[17]

At the same time that Oliphant was appointed editor, the layout of the magazine was changed to that of a standard pulp. At 160 pages, this offered readers much better value for money than the 48-page dime novel format of the first eight issues, even with a price increase from 10 to 15 cents. A question and answer department, "Cross-Trails", was begun, in imitation of a similar feature in Adventure, the most successful pulp magazine of the day, and the format change may also have been done to increase the resemblance of the two magazines, along with a change to the appearance of The Thrill Book's contents page to resemble that of Adventure.[19]

Street & Smith cancelled the magazine after the sixteenth issue, dated October 15. A printers' strike has often been suggested as the reason, though Hersey denied it in his reminiscences, and it is clear that poor sales were at least part of the reason for the cancellation. Stories were still being acquired for the magazine by Street & Smith in November, and since the final issue would have appeared on newsstands some time in September, this implies that the magazine went on hiatus (possibly because of the printers' strike) with the expectation of returning, perhaps on a less frequent schedule. A note in Street & Smith's files records the cancellation date as December 1, 1919, which may indicate the point at which the delay caused by the strike convinced Street & Smith to finally kill the magazine.[6]

Contents and reception

Hersey began by making himself familiar with the work of writers already in the market who were capable of producing the kind of material Ralston wanted. He soon concluded that the new magazine would have to include some reprinted stories alongside the original material. The budget did not permit Hersey to pay rates that would attract top-quality writers, nor even to reprint the best-known stories of the kind he was looking for, and he was forced to use relatively unknown authors such as Perley Poore Sheehan and Robert W. Sneddon. Hersey distributed a "Notice to Writers" that described what he was looking for: "strange, bizarre, occult, mysterious tales ... mystic happenings, weird adventures, feats of leger-de-main, spiritualism, et cetera ... If you have an idea which you have considered too bizarre to write, too weird or strange, let us see it." This did not restrict the submissions to fantasy or science fiction, and as a result Hersey received (and printed) all kinds of fiction, including mysteries, adventures, and love stories,[15] though it may be that he simply did not receive enough good quality science fiction and fantasy to fill the magazine.[21] Hersey later recalled that the notice did not bring in many usable manuscripts: "As a result of the notices in the writers' magazines, I received a thousand manuscripts but was able to buy only ten!"[22]

The first issue included "Wolf of the Steppes", a werewolf story by Greye La Spina. This had been submitted to The Popular Magazine but purchased by Clancy for The Thrill Book in 1918, when Street & Smith began making plans for the new magazine.[22][note 2] The story was the first by La Spina, whose real name was Fanny Greye Bragg; she would go on to publish several more stories in The Thrill Book, and later became a regular contributor to Weird Tales.[22] Another first story was "The Thing That Wept", by Charles Fulton Oursler, who later went on to edit Liberty and to write novels under the name Anthony Abbot.[22][24][25] Two serials were begun in the first issue: "The Jeweled Ibis" by J.C. Kofoed, and "In the Shadows of Race", by J. Hampton Bishop. Both contained enough fantastic or science-fictional elements to fit the original plans for the magazine: "The Jeweled Ibis" was about worshippers of the ancient Egyptian gods, and Bishop's story was about a lost race in Africa, and included intelligent apes.[21] The cover for the first issue was by Sidney H. Riesenberg; Bleiler describes it as "shabby and second-rate" by comparison to cover art in successful magazines of the day such as Adventure and Detective Story Magazine.[20] The May 1 issue included an early short story by Seabury Quinn, "The Stone Image", which features a character named Dr. Towbridge, who would later appear (renamed Dr. Trowbridge) in Quinn's popular occult detective stories about Jules de Grandin, though Quinn had not yet invented de Grandin. Tod Robbins, a well-regarded writer of fantasy, supplied several short pieces, all "shallow mood sketches" without much substance, in the opinion of science fiction historian Mike Ashley.[13] The contributors included Sophie Louise Wenzel, who later published stories in Weird Tales under the name Sophie Wenzel Ellis, but most of the writers from Hersey's editorship, such as George C. Jenks and John R. Coryell—both authors of dime novels—are no longer well-known names.[22]

When Oliphant took over the editorship, he placed notices in writers' magazines looking for more submissions.[26][note 3] Much of the material published under Oliphant's editorship would have been bought by Hersey, making it hard to judge Oliphant's impact.[17] However, it is clear that Oliphant bought more science fiction and fantasy stories than Hersey had done:[13] in particular, Hersey had published almost no stories that were straightforward science fiction, though two he did purchase, Murray Leinster's "A Thousand Degrees Below Zero" and "The Silver Menace", appeared in the first few issues of Oliphant's editorship.[17] Stories such as "The Lost Days" by Trainor Lansing, which dealt with perceptions of time, and "The Ultimate Ingredient" by Greye La Spina, about invisibility, published in August and October respectively, were more evidence of this change in emphasis.[21] The most famous science fiction to appear in The Thrill Book was Francis Stevens' novel The Heads of Cerberus, which was one of the earliest fictional depictions of alternate timelines.[13][28] In addition to increasing the science fiction content, Oliphant also brought in authors who were better known than those published under Hersey's editorship, including H. Bedford-Jones and William Wallace Cook.[29] It seems likely that the fiction budget increased when Oliphant took control, and he used this to pay higher word-rates to the better writers. Hersey had paid about a cent per word for fiction, but Bedford-Jones received $800 for "The Opium Ship", which was a rate of between 2.5 and 3 cents per word. However, Francis Stevens was paid only $400, or less than a cent per word, for the much longer novel The Heads of Cerberus.[30] Poetry continued to appear, including several more poems by Hersey, and also including "Dissonance" by Clark Ashton Smith, whom Hersey had contacted in March asking for submissions in what Will Murray describes as "a rare instance of Hersey's editorial foresight".[28]

When The Thrill Book ceased publication, Street & Smith had numerous manuscripts in inventory that had been purchased for the magazine. These were offered to other Street & Smith magazines such as Sea Stories over the next few years. Greye La Spina bought back her manuscript to "The Dead Wagon" in 1927 and re-sold it to Weird Tales. Francis Stevens had sold three serials and three short stories to The Thrill Book that remained unpublished: one of the serials, Serapion, was published in Argosy in 1920, but the fate of the other two is not known—they may have been earlier titles for known works of hers. The three short stories are not known to have been published elsewhere. In 1940, John L. Nanovic, the editor of Doc Savage and The Shadow, reviewed the remaining Thrill Book manuscripts, and suggested to Ralston that a few stories might be publishable in Love Story Magazine, and also suggested a few stories that John W. Campbell might be interested in for Unknown. The following year Oliphant reviewed ten of the manuscripts and returned them to Nanovic with his recommendations. Campbell reviewed three of them and declined to take any; he also declined to take Murray Leinster's "The Great Catastrophe", which had been submitted to The Thrill Book and found independently of Nanovic's review. Other magazines that considered and rejected the stories Oliphant recommended included Clues, Mystery, and Detective Story Magazine.[31] The only story from The Thrill Book's inventory that was used from this review was Clyde Broadwell's "The Speed Demon's Vendetta", which was rewritten and published in The Avenger in March 1942 under the pseudonym "Denby Brixton", which Broadwell had used for a story he had sold to The Thrill Book.[32][33]

In 1976 the manuscripts were reviewed again by Will Murray. By this time they had been donated to Syracuse University by Condé Nast, which had acquired Street & Smith in 1961. The ten stories reviewed by Oliphant were found and plans were made for Odyssey Publications to publish a paperback edition of Thrill Book material including these stories along with some reprints. The following year another group of Thrill Book manuscripts was found in the Syracuse collection, including Leinster's "The Great Catastrophe" and La Spina's "The Bracelet", and the planned contents of the anthology were revised to include some of this material. None of the Francis Stevens stories were found in either group of manuscripts. One story, "As It Is Written", by De Lysle Ferree Cass, was misidentified by Murray as the work of Clark Ashton Smith, and this led to delays in publication as Odyssey made separate plans to publish the story under Smith's name. The misidentification was not discovered until after the story appeared in print in 1982. Four years later, Odyssey went out of business, and the anthology of Thrill Book material never appeared.[34]

Because The Thrill Book was only sold in selected parts of the US, copies of the magazine are very scarce and are highly prized by pulp magazine collectors.[35] Despite its rarity, or perhaps because of it, it has been often described as the first science fiction and fantasy magazine ever published, though more recent assessments by science fiction and pulp historians agree instead that the magazine was a failed attempt at specialization. In the words of Will Murray, the view that The Thrill Book is the first such magazine is "erroneously held by many", and he adds that it was "merely a prologue to the Golden Era of periodical weird fiction". In Murray's opinion it might well have become a dominant force in the genre had it continued publication.[35] Richard Bleiler comments that "it was a magazine that somehow became a symbol to a generation of pulp readers ... it was the first eidetic flash of a dream that would later come into being with Weird Tales",[36][36] and in Mike Ashley's opinion it was just "a step towards a full-blown fantasy magazine".[21]

Bibliographic details

The Thrill Book was published by Street & Smith. Initially the magazine was saddle-stapled, 10 3⁄4 in by 8 in, 48 pages long, and priced at 10 cents. This changed with the ninth issue, dated July 1, 1919, to pulp format, with 160 pages, priced at 15 cents. The editor was Harold Hersey from March 1, 1919 to June 15, 1919, and Ronald Oliphant thereafter.[13] There were eight issues to the first volume, six in the second, and two in the third and final volume.[13][37] Hersey later recalled that he had heard of a Thrill Book Quarterly being issued, but no evidence of such a magazine has been found.[38]

Two issues of The Thrill Book have been reprinted in facsimile editions, both by Wildside Press: the September 1, 1919 issue, published in 2005, and the first issue, March 1, 1919, which appeared in 2011.[29]

Notes

- ↑ The term "different" for this sort of story had been coined by Robert A. Davis, one of the editors at Munsey.[4]

- ↑ The story had been purchased by Street & Smith on June 28, 1918.[23]

- ↑ Murray Leinster recalled later that Hersey had advertised in the writers' magazines, but according to Richard Bleiler no such notices have been found and it appears likely from other evidence that Leinster confused Oliphant and Hersey in his recollections.[27] Hersey himself mentioned notices he had posted in the magazines, in a reminiscence he wrote in 1955, so he may have done so despite no evidence having yet been found.[22]

References

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 252.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 250.

- 1 2 Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike (July 18, 2012). "Pulp". SF Encyclopedia. Gollancz. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Murray (2011), p. 11.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), pp. 4–5.

- 1 2 Murray (2011), pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 4.

- ↑ Murray (2011), pp. 11–16.

- ↑ Bleiler, Richard (October 22, 2014). "Hersey, Harold". SF Encyclopedia. Gollancz. Retrieved December 20, 2014.

- ↑ Hulse (2013), p. 218.

- ↑ Murray (2011), pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ashley (1985), pp. 661–664.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 7.

- 1 2 Murray (2011), p. 15.

- 1 2 Bleiler (1991), p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 Murray (2011), p. 17.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), pp. 10–13.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), pp. 13–15.

- 1 2 Bleiler (1991), pp. 6–7.

- 1 2 3 4 Ashley (2000), pp. 37–40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Murray (2011), p. 16.

- ↑ Murray (2011), p. 27, note 9.

- ↑ Blottner (2011), p. 293.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 34.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), pp. 6, 16.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 6.

- 1 2 Murray (2011), p. 19.

- 1 2 Bleiler, Richard; Ashley, Mike (April 8, 2013). "The Thrill Book". SF Encyclopedia. Gollancz. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), p. 15.

- ↑ Murray (2011), pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Murray (2011), pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Murray (2011), pp. 25–26.

- 1 2 Murray (2011), p. 26.

- 1 2 Bleiler (1991), p. 20.

- ↑ Bleiler (1991), pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Murray (2011), p. 20.

Sources

- Ashley, Mike (1985). "The Thrill Book". In Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike. Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Bleiler, Richard (1991). The Annotated Index to The Thrill Book. Mercer Island, Washington: Starmont House, Inc. ISBN 1-55742-205-2. ISSN 0738-0127.

- Blottner, Gene (2011). Columbia Pictures Movie Series, 1926–1955: The Harry Cohn Years. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3353-7.

- Hulse, Ed (2013). The Blood 'n' Thunder Guide to Pulp Fiction. Morris Plains, New Jersey: Murania Press. ISBN 978-1-4910-1093-8.

- Murray, Will (2011). "The Thrill Book Story". Pulp Vault. Barrington Hills, Illinois: Tattered Pages Press (14).

External links

![]() Media related to The Thrill Book at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Thrill Book at Wikimedia Commons

- "The Thrill Book". archive.org. May 15, 1919.

- "The Thrill Book". archive.org. June 1, 1919.

- "The Thrill Book". archive.org. June 15, 1919.

- "The Thrill Book". archive.org. July 1, 1919.

- "The Thrill Book". archive.org. August 1, 1919.