The Thing from Another World

| The Thing from Another World | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Christian Nyby |

| Produced by | Edward Lasker |

| Screenplay by |

Charles Lederer Uncredited: Howard Hawks Ben Hecht |

| Based on |

Who Goes There? 1938 novella by John W. Campbell, Jr. |

| Starring |

Margaret Sheridan Kenneth Tobey Douglas Spencer Robert O. Cornthwaite James Arness |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

| Cinematography | Russell Harlan, ASC |

| Edited by | Roland Gross |

Production company |

Winchester Pictures Corporation |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $1.95 million (US rentals)[2] |

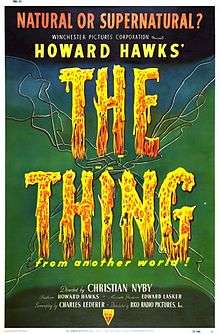

The Thing from Another World is a 1951 American black-and-white science fiction-horror film, directed by Christian Nyby, produced by Edward Lasker for Howard Hawks' Winchester Pictures Corporation, and released by RKO Pictures. The film stars Kenneth Tobey, Margaret Sheridan, Robert Cornthwaite, and Douglas Spencer. James Arness plays The Thing, but he is difficult to recognize in costume and makeup due to both low lighting and other effects used to obscure his features. The film is based on the 1938 novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell (writing under the pseudonym of Don A. Stuart).[3]

The storyline concerns a U.S. Air Force crew and scientists who find a crashed flying saucer and a body frozen nearby in the Arctic ice. Returning to their remote research outpost with the humanoid body in a block of ice, they are forced to defend themselves against this malevolent, plant-based alien when it is accidentally revived.[4]

Plot

A United States Air Force crew is dispatched from Anchorage, Alaska at the request of Dr. Carrington (Robert Cornthwaite), the chief scientist of a North Pole scientific outpost. They have evidence that an unknown flying craft has crashed in their vicinity, so reporter Ned Scott (Douglas Spencer) tags along for the story.

Dr. Carrington later briefs Captain Hendry (Kenneth Tobey) and his airmen, and Dr. Redding (George Fenneman) shows photos of a flying object moving erratically before crashing -- not the movements of a meteorite. Following erratic magnetic pole anomalies, the crew and scientists fly to the crash site where the mysterious craft lies buried beneath refrozen ice. As they spread out to outline the craft's general shape, the men realize they are standing in a circle; they have discovered a crashed flying saucer. They try de-icing the buried craft with thermite heat bombs, but only ignite its metal alloy, causing an explosion that destroys the saucer. Their Geiger counter then points to a slightly radioactive frozen shape buried nearby in the refrozen ice.

They excavate a large block of ice around what appears to be a tall body and fly it to the research outpost, just as a major storm moves in, cutting off their communications with Anchorage. Some of the scientists want to thaw out the body, but Captain Hendry insists on waiting until he receives further instructions from the Air Force. Later, Corporal Barnes (William Self) takes the second watch over the ice block and to avoid looking at the body within, covers it with an electric blanket that the previous guard left turned on. As the ice slowly melts, the Thing inside revives; Barnes panics and shoots at it with his sidearm, but the alien escapes into the raging storm. The Thing is attacked by sled dogs and the airmen recover a severed arm.

A microscopic examination of a tissue sample reveals that the arm is vegetable rather than animal matter, demonstrating that the alien is a very advanced form of plant life. As the arm warms to ambient temperature, it ingests some of the dogs' blood covering it, and the hand begins moving. Seed pods are discovered in the palm. The Air Force personnel believe the creature is a danger to all of them, but Dr. Carrington is convinced that it can be reasoned with and has much to teach them. Carrington deduces their visitor requires blood to survive and reproduce. He later discovers the body of a dead sled dog hidden in the outpost's greenhouse. Carrington has Dr. Voorhees (Paul Frees), Dr. Olsen (William Neff) and Dr. Auerbach stand guard overnight, waiting for The Thing to return.

Carrington secretly uses blood plasma from the infirmary to incubate seedlings grown from the alien seed pods. The strung-up bodies of Olsen and Auerbach are discovered in the greenhouse, drained of blood. Dr. Stern is almost killed by the Thing but escapes. Hendry rushes to the greenhouse after hearing about the bodies, and is attacked by the alien. Hendry slams the door on the Thing's regenerated arm as it tries to grab him. The alien then escapes through the greenhouse's exterior door, breaking into another building in the compound. Nikki Nicholson (Margaret Sheridan), Carrington's secretary, reluctantly updates Hendry when he asks about missing plasma and confronts Carrington in his lab, where he discovers the alien seeds have grown at an alarming rate. Following Nicholson's suggestion, Hendry and his men lay a trap in a nearby room: after dousing the alien with buckets of kerosene, they set the thing ablaze with a flare gun, forcing it to jump through a closed window into the arctic storm.

Nicholson notices that the temperature inside the station is falling; a heating fuel line has been sabotaged by the alien. The cold forces everyone to make a final stand near the generator room. They rig an electrical "fly trap", hoping to electrocute their visitor. As the Thing advances, Carrington shuts off the power and tries to reason with it, but is knocked aside. On Hendry's direct order that nothing of the Thing remain, it is reduced by arcs of electricity to a smoldering pile of ash; Dr. Carrington's growing seed pods and the Thing's severed arm are then destroyed.

When the weather clears, Scotty files his "story of a lifetime" by radio to a roomful of reporters in Anchorage. Scotty begins his broadcast with a warning: "Tell the world. Tell this to everybody, wherever they are. Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies".

Cast

- Margaret Sheridan as Nikki Nicholson

- Kenneth Tobey as Captain Patrick Hendry

- Robert Cornthwaite as Dr. Arthur Carrington

- Douglas Spencer as "Scotty" (Ned Scott)

- James Young as Lt. Eddie Dykes

- Dewey Martin as Crew Chief (Bob)

- Robert Nichols as Lt. Ken MacPherson

- William Self as Corporal Barnes

.

- Eduard Franz as Dr. Stern

- Paul Frees as Dr. Voorhees

- John Dierkes as Dr. Chapman

- George Fenneman as Dr. Redding

- Everett Glass as Dr. Wilson

- Edmund Breon as Dr. Ambrose

- Sally Creighton as Mrs. Chapman

- David McMahon as General Fogerty

- James Arness as 'The Thing'

Production

No actors are named during the film's dramatic "slow burning letters through background" opening title sequence; the cast credits appear at the end of the film.[3]

Appearing in a small role was George Fenneman, who at the time was gaining fame as Groucho Marx's announcer on the popular quiz show You Bet Your Life. Fenneman later said he had difficulty with the overlapping dialogue in the film.[5]

The film was partly shot in Glacier National Park and interior sets built at a Los Angeles ice storage plant.[3]

The film took full advantage of the national feelings of the time to help enhance the horror elements of the story. The film reflected a post-Hiroshima skepticism about science and negative views of scientists who meddle with things better left alone. In the end it is American servicemen and several sensible scientists who win the day over the alien invader.[3]

Screenplay

The film was loosely adapted by Charles Lederer, with uncredited rewrites from Howard Hawks and Ben Hecht, from the 1938 novella Who Goes There? by John W. Campbell, Jr.; the story was first published in Astounding Science Fiction under Campbell's pseudonym Don A. Stuart (Campbell had just become Astounding's managing editor when his novella appeared in its pages).[3]

The film's screenplay changes the fundamental nature of the alien as presented in Campbell's 1938 novella: Lederer's "Thing" is a humanoid life form whose cellular structure is closer to vegetation, although it must feed on blood to survive; reporter Scott even refers to it in the film as a "super carrot." The internal, plant-like structure of the creature makes it impervious to bullets but not other destructive forces. Campbell's "Thing" is a life form capable of assuming the physical and mental characteristics of any living thing it encounters; this characteristic was later realized in John Carpenter's adaptation of the novella, the 1982 film The Thing.[3]

Director

There is debate as to whether the film was directed by Hawks with Christian Nyby receiving the credit so that Nyby could obtain his Director’s Guild membership,[6][Note 1][8] or whether Nyby directed it with considerable input in both screenplay and advice in directing from producer Hawks[9] for Hawks' Winchester Pictures, which released it through RKO Radio Pictures Inc. Hawks gave Nyby only $5,460 of the $50,000 director's fee that RKO paid and kept the rest, but Hawks denied that he directed the film.[5]

Cast members disagree on Hawks' and Nyby's contributions. Tobey said that "Hawks directed it, all except one scene"[10] while, on the other hand, Fenneman said that "Hawks would once in a while direct, if he had an idea, but it was Chris' show." Cornthwaite said that "Chris always deferred to Hawks, ... Maybe because he did defer to him, people misinterpreted it."[5] Although Self has said that "Hawks was directing the picture from the sidelines",[11] he also has said that "Chris would stage each scene, how to play it. But then he would go over to Howard and ask him for advice, which the actors did not hear ... Even though I was there every day, I don't think any of us can answer the question. Only Chris and Howard can answer the question."[5]

One of the film's stars, William Self, later became President of 20th Century Fox Television.[12] In describing the production, Self said, "Chris was the director in our eyes, but Howard was the boss in our eyes."[5]

At a reunion of The Thing cast and crew members in 1982, Nyby said:[5]

Did Hawks direct it? That's one of the most inane and ridiculous questions I've ever heard, and people keep asking. That it was Hawks' style. Of course it was. This is a man I studied and wanted to be like. You would certainly emulate and copy the master you're sitting under, which I did. Anyway, if you're taking painting lessons from Rembrandt, you don't take the brush out of the master's hands.[5]

Reception

Critical and box office reception

The Thing from Another World was released in April 1951.[3] By the end of that year, the film had accrued $1,950,000 in distributors' domestic (U. S. and Canada) rentals, making it the year's 46th biggest earner, beating all other science fiction films released that year, including The Day The Earth Stood Still and When Worlds Collide.[13] [Note 2]

Bosley Crowther in The New York Times observed, "Taking a fantastic notion (or is it, really?), Mr. Hawks has developed a movie that is generous with thrills and chills…Adults and children can have a lot of old-fashioned movie fun at 'The Thing', but parents should understand their children and think twice before letting them see this film if their emotions are not properly conditioned."[14] "Gene" in Variety complained that the film "lacks genuine entertainment values."[15] More than 20 years after its theatrical release, science fiction editor and publisher Lester del Rey compared the film unfavorably to the source material, John W. Campbell's Who Goes There?, calling it "just another monster epic, totally lacking in the force and tension of the original story."[16]

The Thing is now considered by many to be one of the best films of 1951.[17][18][19] The film holds an 88% "Fresh" rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, with the consensus that the film "is better than most flying saucer movies, thanks to well-drawn characters and concise, tense plotting."[20] In 2001, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[21] [22] Additionally, Time magazine named The Thing from Another World "the greatest 1950s sci-fi movie." [23][24]

Legacy

- The Thing from Another World is considered one of the great science fiction films of the 1950s.[25]

American Film Institute lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – #87[26]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- The Thing – Nominated Villain[27]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Watch the skies, everywhere, keep looking! Keep watching the skies!" – Nominated[28]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated[29]

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – Nominated Sci-Fi Film[30]

Related productions

- A more faithful adaptation of Campbell's story was directed by John Carpenter and released in 1982 under the title The Thing.[31] It paid homage to the 1951 film by using the same "slow burning letters through background" opening title sequence.

- Matthijs van Heijningen Jr. made a 2011 prequel to Carpenter's 1982 film using the same title, The Thing.[32]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "And let's get the record straight. The movie was directed by Howard Hawks. Verifiably directed by Howard Hawks. He let his editor, Christian Nyby, take credit. But the kind of feeling between the male characters — the camaraderie, the group of men that has to fight off the evil — it's all pure Hawksian." [7]

- ↑ "Rentals" refers to the distributor/studio's share of the box office gross, which, according to Gebert, is roughly half of the money generated by ticket sales.[13]

Citations

- ↑ "The Thing from Another World: Detail View." American Film Institute. Retrieved: May 19, 2014.

- ↑ "The Top Box Office Hits of 1951." Variety, January 2, 1952.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Warren 1982, pp. 151–163.

- ↑ Hamilton 2007, pp. 8–11.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fuhrmann, Henry "A 'Thing' to His Credit." Los Angeles Times, May 25, 1997. Retrieved: April 20, 2012.

- ↑ Weaver 2003, p. 346.

- ↑ Carpenter, John (speaker). "Hidden Values: The Movies of the '50s." Turner Classic Movies, September 4, 2001.

- ↑ "Christian Nyby: About This Person." The New York Times. Retrieved: January 10, 2015.

- ↑ Mast 1982, p. 344.

- ↑ Matthews 1997, p. 14.

- ↑ Weaver 2003, p. 272.

- ↑ "Self Promoted to Presidency of 20th-Fox TV"Daily Variety (1968 11 1) Pgs. 1;26

- 1 2 Gebert 1996, p. 156.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley. "The Screen: Two films have local premieres; 'The Thing', an eerie scientific number by Howard Hawks, opens at the Criterion." The New York Times, May 3, 1951.

- ↑ Willis 1985, p. 86.

- ↑ del Ray, Lester 1973, p. 4.

- ↑ "The Greatest Films of 1951." AMC Filmsite.org. Retrieved: May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "The Best Movies of 1951 by Rank ." Films101.com. Retrieved: May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1951." IMDb.com. Retrieved: May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "'The Thing from Another World Movie Reviews, Pictures." Rotten Tomatoes, Retrieved: May 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry (press release)." Library of Congress. Retrieved: April 20, 2012.

- ↑ "National Film Registry." National Film Registry (National Film Preservation Board, Library of Congress). Retrieved: November 26, 2011.

- ↑ "1950s Sci-Fi Movies: Full List." Time, December 12, 2008. Retrieved: June 20, 2010.

- ↑ "1950s Sci-Fi Movies." Time, December 12, 2008. Retrieved: June 20, 2010.

- ↑ Booker 2010, p. 126.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills." American Film Institute|, Retrieved: March 7, 2012.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains: The 400 Nominated Characters." American Film Institute. Retrieved: March 7, 2012.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes: The 400 Nominated Movie Quotes." American Film Institute. Retrieved: March 7, 2012.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition): Official Ballot." American Film Institute. Retrieved: March 7, 2012.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10: The Official Ballot." American Film Institute. Retrieved: March 7, 2012.

- ↑ Maçek III, J.C. "Building the Perfect Star Beast: The Antecedents of 'Alien'." PopMatters, November 21, 2012. Retrieved: January 10, 2015.

- ↑ Collura, Scott. "Exclusive: Moore Talks The Thing." movies.ign.com. Retrieved: January 10, 2015.

Bibliography

- Booker, M. Keith. Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction Cinema. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2010. ISBN 978-0-8108-5570-0.

- Campbell, John W. and William F. Nolan. Who Goes There? The Novella That Formed The Basis Of 'The Thing'." Rocket Ride Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0-9823322-0-7.

- del Ray, Lester. "The Three Careers of John W. Campbell", introduction to The Best of John W. Campbell 1973. ISBN 0-283-97856-2.

- "Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – The Seeds of Doom – Details." BBC.

- Gebert, Michael. The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1996. ISBN 0-668-05308-9.

- Hamilton, John. The Golden Age and Beyond: The World of Science Fiction. Edina Minnesota: ABDO Publishing Company, 2007. ISBN 978-1-59679-989-9.

- Mast, Gerald. Howard Hawks: Storyteller. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0-19503-091-4.

- Matthews, Melvin E. Jr. 1950s Science Fiction Films and 9/11: Hostile Aliens, Hollywood, and Today's News. New York: Algora Publishing, 1997. ISBN 978-0-87586-499-0.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies, Vol I: 1950–1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

- Weaver, Tom. Eye on Science Fiction: 20 Interviews With Classic Sf and Horror Filmmakers. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003. 0-7864-1657-2.

- Weaver, Tom. "Kenneth Tobey Interview." Double Feature Creature Attack. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003. ISBN 978-0-78641-366-9.

- Willis, Don, ed. Variety's Complete Science Fiction Reviews. New York: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1985. ISBN 0-8240-6263-9.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Thing from Another World |

- The Thing from Another World at AllMovie

- The Thing from Another World on IMDb

- The Thing from Another World at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Thing from Another World at the TCM Movie Database

- The Thing from Another World at the American Film Institute Catalog