Picnic at Hanging Rock (novel)

|

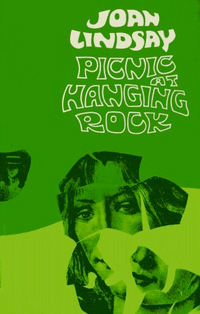

First edition cover | |

| Author | Joan Lindsay |

|---|---|

| Country | Australia |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical novel |

| Publisher |

F. W. Cheshire Penguin (paperback) |

Publication date | 1967 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) |

| Pages | 212 (first printing) |

Picnic at Hanging Rock is a 1967 Australian historical fiction novel by Joan Lindsay. Its plot focuses on a group of female students at an Australian women's college in 1900 who inexplicably vanish at Hanging Rock while on a Valentine's Day picnic. It also explores the outlying effects the disappearances have on the school and local community. The novel was first published in 1967 in Australia by Cheshire Publishing and was reprinted by Penguin in 1975. It is widely considered by critics to be one of the most important Australian novels of all time.

Though the events depicted in the novel are entirely fictional, it is framed as though it is a true story, corroborated by ambiguous pseudohistorical references. Its irresolute conclusion has sparked significant public, critical, and scholarly analysis, and the narrative has become a part of Australia's national folklore as a result. Lindsay claimed to have written the novel over two weeks at her home Mulberry Hill in Baxter, on Victoria's Mornington Peninsula, after having successive dreams of the narrated events.

An excised final chapter of the novel was published posthumously as a standalone book in 1987, titled The Secret of Hanging Rock, and also included critical commentary and interpretive theories on the novel. Another book, titled The Murders at Hanging Rock, was published in 1980, proposing varying interpretations. The novel has been adapted across numerous mediums, most famously in the 1975 critically acclaimed film of the same name by director Peter Weir.

Plot

The novel begins with a brief foreword, which reads:

"Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction, my readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year nineteen hundred, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important."

At Appleyard College, an upper-class women's private boarding school, a picnic is being planned for the students under the supervision of Mrs. Appleyard, the school's headmistress. The picnic entails a day trip to Hanging Rock in the Mount Macedon area, Victoria, on St. Valentine's Day in 1900. One of the students, Sara, who is in trouble with Mrs. Appleyard, is not allowed to go. Sara's close friend Miranda goes without her. When they arrive, the students lounge about and eat a lunch. Afterward, Miranda goes to climb the monolith with classmates Edith, Irma, and Marion. The girls' mathematics teacher, Greta McCraw, follows behind them. As they ascend the rock, in a dreamlike episode, Miranda, Marion, and Irma vanish into the rock while Edith watches; she returns to the picnic in hysterics, disoriented and with no memory of what occurred. Miss McCraw is also nowhere to be accounted for. The school scours the rock in search of the girls and their teacher, but they are not found.

The disappearances provoke much local concern and international sensation with rape, abduction, and murder being assumed as probable explanations. Several organized searches of the picnic grounds and the area surrounding the rock itself turn up nothing. Meanwhile, the students, teachers and staff of the college, as well as members of the community, grapple with the riddle-like events. Albert Crundall, a local coachman, embarks on a private search of the rock and discovers Irma, unconscious and on the verge of death. When he fails to return from his search, he is found at the rock with Irma in an unexplained daze.

Concerned parents begin withdrawing their daughters from the prestigious college, prompting various staff to leave; the college's handyman and maid quit their jobs, and the French instructor, Mlle. Dianne de Poitiers, announces that she will be getting married and leaving the college as well. A junior governess at the college also leaves with her brother, only to be killed in a hotel fire. Amidst the unrest both in and around the college, Sara vanishes, only to be found days later, having committed suicide. Mrs. Appleyard, distraught over the events that have occurred, also kills herself by jumping from a peak on Hanging Rock.

In a pseudo-historical afterword purportedly extracted from a 1913 Melbourne newspaper article, it is written that both the college, and the Woodend Police Station where records of the investigation were kept, were destroyed by a brush fire in the summer of 1901. In 1903, rabbit hunters came across a lone piece of frilled calico at the rock, but the women were still never found.

Excised final chapter

According to her editor Sandra Forbes, Lindsay's original draft of the novel included a final chapter in which the mystery was resolved. At her editor's suggestion, Lindsay removed it prior to publication.[1] Chapter Eighteen, as it is known, was published posthumously as a standalone book in 1987 as The Secret of Hanging Rock by Angus & Robertson Publishing.

The chapter opens with Edith fleeing back to the picnic area while Miranda, Irma, and Marion push on. Each girl begins to experience dizziness and feel as if she is "being pulled from the inside out." A woman suddenly appears climbing the rock in her underwear, shouting, "Through!", and then faints. This woman is not referenced by name and is apparently a stranger to the girls, yet the narration suggests she is Miss McCraw. Miranda loosens the woman's corset to help revive her. Afterwards, the girls remove their own corsets and throw them off the cliff. The recovered woman points out that the corsets appear to hover in mid-air as if stuck in time, and that they cast no shadows. She and the girls continue together. They then throw their corsets from the top of the cliff but, instead of falling, the corsets stand still in mid-air. The girls then encounter what is described as "a hole in space", by which they physically enter a crack in the rock; the unnamed woman transforms into a lizard-like creature and disappears into the rock. Marion follows her, then Miranda, but when Irma's turn comes, a balanced boulder (the hanging rock) slowly tilts and blocks the way. The chapter ends with Irma "tearing and beating at the gritty face on the boulder with her bare hands".

The missing material amounts to about 12 pages; the remainder of the publication The Secret at Hanging Rock contains discussion by other authors, including John Taylor and Yvonne Rousseau. The suspension of the corsets and description of the hole in space suggest that the girls have encountered some sort of time warp, which is compatible with Lindsay's fascination with and emphasis on clocks and time in the novel.[2]

Conception

Lindsay claimed to have written the novel based on an idea she had in a dream. In a 2017 article in The Age, it was noted: "The dream had centred on a summer picnic at a place called Hanging Rock, which Joan knew well from her childhood holidays. Joan told Rae [her housekeeper] that the dream had felt so real that when she awoke at 7.30am, she could still feel the hot summer breeze blowing through the gum trees and she could still hear the peals of laughter and conversation of the people she'd imagined, and their gaiety and lightness of spirit as they set out on their joyful picnic expedition."[5]

According to her housekeeper at the time, the events of the novel were dreamt by Lindsay successively.[5][6] Several years after the publication of the novel, Lindsay would recount the experience of writing it as such: "Picnic at Hanging Rock really was an experience to write, because I was just impossible when I was writing it. I just sort of thought about it all night and in the morning I would go straight up and sit on the floor, papers all around me, and just write like a demon!"[5]

The novel was written over a total of two weeks at Lindsay's home in Mulberry Hill.[5] In thinking of a title, Lindsay recalled the painting Hanging Rock by William Ford, which had hung in her husband Daryl's office,[7] and chose to incorporate it into the title as it was "simple and pretty, and belied the horrors hidden within."[5] In an interview after Lindsay's death, academic Terrence O'Neill, who had befriended Lindsay, remarked the supernatural elements of the novel: "It was clear that [Joan] was interested in Spiritualism, and longed for some spiritual dimension in her life, but she didn't feel safe bringing that side of her out in front of her husband. So I think she channelled it into her writing. I know she was very interested in Arthur Conan Doyle and his belief in and theories about Spiritualism, nature and the existence of spirits."[5]

The novel was imported for sale in the United States, and would receive its first publication there in 2014 by Penguin Random House.[8] In the United Kingdom, the novel was printed in several editions by Vintage, in 1998[9] and 2013.[10]

Basis in reality

Sandra Forbes, editor, on the novel's truth claim[5]

Picnic at Hanging Rock is written in the form of a true story, and even begins and ends with a pseudohistorical prologue and epilogue, reinforcing the mystery that has generated significant critical and public interest since its publication in 1967.[5][11] However, while the geological feature, Hanging Rock, and the several towns mentioned are actual places near Mount Macedon, the story itself is entirely fictitious.[12][13] Lindsay had done little to dispel the myth that the story is based on truth, in many interviews either refusing to confirm it was entirely fiction,[14] or hinting that parts of the book were fictitious, and others were not. For instance, Valentine's Day, 14 February 1900 was a Wednesday, not a Saturday as depicted in the story.[15]

Appleyard College was to some extent based on Clyde Girls' Grammar School at East St Kilda, Melbourne, which Joan Lindsay attended as a day-girl while in her teens. Incidentally, in 1919 this school was transferred to the town of Woodend, Victoria, about 8 km southwest of Hanging Rock.[16]

When asked in a 1974 interview about whether or not the novel was based in truth, Lindsay responded: "Well, it was written as a mystery and it remains a mystery. If you can draw your own conclusions, that's fine, but I don't think that it matters. I wrote that book as a sort of atmosphere of a place, and it was like dropping a stone into the water. I felt that story, if you call it a story—that the thing that happened on St. Valentine's Day went on spreading, out and out and out, in circles."[17] The unsolved mystery of the disappearances in the novel aroused enough lasting public interest that in 1980 a book of hypothetical solutions (by Yvonne Rousseau) was published, called The Murders at Hanging Rock.[18]

Impact on local tourism

In 2017, in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the novel's publication, an Australian doctoral student named Amy Spiers began the "Miranda Must Go" campaign, criticizing the novel's propagation of itself as a true story in relationship to local tourism at Hanging Rock.[19] Spiers argued that the focus on the fictional narrative obscures its longer history and connection with the Aborigines:

At Hanging Rock we've become obsessed with the myth almost to the point where we sort of tell it as though it is a true story, but we completely ignore the true losses that have happened there. Most of the Aboriginal people living in that area died of smallpox or were murdered by colonists or removed to Coranderrk [Aboriginal Reserve in Healesville] in 1836 ... It's just fascinating to me that we keep choosing to be haunted by a [fictitious] story rather than the real losses that have occurred in that place.[19]

Spiers cited the common practice among tourists to scream "Miranda!" from atop the rock as an example of the site's strong cultural associations with the novel and its film adaptation; she also noted that the visitors' centre caters significantly to the myth of the "missing schoolgirls," with dioramas, videos, panels and soundtracks from both the novel and the film, while the real history of the monolith and its significance to the indigenous culture was less acknowledged.[20] Supporters of the campaign held a protest on St. Valentine's Day 2017 at the rock.[20]

In response to the campaign, Luke Spielvogel, the president of Friends of Hanging Rock, noted that the novel and particularly, the character of Miranda, captured the "ethereal, mysterious nature of the rock"; he also suggested the novel and character should remain part of the "broader tapestry" of the site:

For 40,000 years Hanging Rock has brought people together, and Miranda and the film and the book are all part of that story. But a significant part of that story was to understand the Indigenous history and further investigate the Indigenous name ... We focus on one aspect of popular culture around Hanging Rock, and I think what Amy is trying to do is tell a broader story, and we certainly support that. [19]

Publication history

The novel was first printed in Australia by F.W. Cheshire, released on 1 November 1967.[5] It was reprinted in paperback by Penguin Books' Australian division in 1975, printed in conjunction with the release of the film adaptation.[21][22] A hardback illustrated edition was also printed in Australia in 1987, also by Penguin.[23] It would receive another reprinting by Penguin Books Australia in 2013 as part of the "Penguin Australian Classics" series.[24]

Critical analysis

Picnic at Hanging Rock is considered by many critics to be one of the most important Australian novels of all time.[25][26] Much of the critical and scholarly interest in the novel has centered on its mysterious conclusion, as well as its depiction of Australia's natural environment in contrast with the Victorian population of the newly established British colony.[lower-alpha 2] In 1987, literary scholar Donald Bartlett drew comparisons between Lindsay's treatment of the rock with that of Malabar Hill in E. M. Forster's A Passage to India, which has been interpreted as a metaphor for Pan, the Greek god of the wild: "There is more, of course, to A Passage to India than Pan motifs, for example symbols such as the snake, the wasp and the undying worm, not to mention the vast panorama of India's religions. But I believe it probable that Joan Lindsay consciously borrowed the elements [from A Passage to India]."[28]

Literary scholar Kathleen Steele argues in her essay "Fear and Loathing in the Australian Bush: Gothic Landscapes in Bush Studies and Picnic at Hanging Rock" that the novel's treatment of landscape and its missing characters is reflective of Australia's national history and the relationship between the rock and the Aboriginal population: "The silence surrounding Aborigines, and the manner in which Europeans foregrounded "geographical, historical and cultural difference and discontinuity," yet denied Aborigines either presence or history, created a gothic consciousness of "something deeply unknowable and terrifying in the Australian landscape. .. Lindsay provokes a reflection on the understanding of Australia as an un-peopled land where nothing of consequence occurred until the British gave it a history."[27]

Steele further notes that Lindsay's "gothic landscapes raise doubts that the majority [of Australians] ever subscribed" to the notion that the country and its natural environment was unmarked by a history prior to the arrival of the British colony.[29]

Adaptations

Film

The first film adaptation of the book was a short by Tony Ingram, a fourteen-year-old filmmaker, who got permission from Joan Lindsay to adapt her book as The Day of Saint Valentine. However, only about ten minutes of footage was filmed before the rights were optioned to Peter Weir for his more famous feature-length version, and the production was permanently shelved. The completed footage is included on some DVD releases of Weir's film.[30]

The feature film version of Picnic at Hanging Rock premiered at the Hindley Cinema Complex in Adelaide on 8 August 1975. It became an early film of the Australian New Wave and is arguably Australia's first international hit film.[5]

Theatre

Picnic at Hanging Rock was adapted by playwright Laura Annawyn Shamas in 1987 and published by Dramatic Publishing Company. Subsequently, it has had many productions in the US, Canada, and Australia. There have also been musical adaptations of the novel.

A stage-musical adaptation, with book, music, and lyrics by Daniel Zaitchik, was scheduled to open in New York City in the fall of 2012.[31] The musical received a 2007 staged reading at New York's Lincoln Center,[32] and further workshop development at the 2009 O'Neill Theater Center National Music Theater Conference.[33] The musical had its world premiere on 28 February 2014 at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah under the direction of Jim Christian.[34]

In 2016, the Malthouse Theatre in Melbourne showed a stage adaptation directed by Matthew Lutton.[35] Another adaptation opened in January 2017 at The Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh, Scotland, working alongside Australian theatre makers Malthouse Theatre, Melbourne and Black Swan State Theatre Company.[36]

Radio

In 2010, BBC Radio 4 broadcast a radio adaptation.[37] The cast included Simon Burke, Penny Downie, Anna Skellern and Andi Snelling.[38]

Miniseries

On September 6, 2016, it was announced that Fremantle Media and pay-TV broadcaster, Foxtel will be producing a six-part miniseries, to be broadcast in 2017.[39]

See also

Notes

Explanatory footnotes

- ↑ Lindsay spent the majority of her early life studying art, and was a graduate of the National Gallery of Victoria Art School.[3] Donald Barrett further notes Lindsay's role as a painter as a potential source of influence in her writing, specifically in Picnic at Hanging Rock.[4]

- ↑ Both Donald Bartlett and Kathleen Steele are significantly interested in the role of the Australian Bush as it is depicted in Picnic at Hanging Rock, specifically the interaction between the "untamed" natural environment and the newly-arrived Victorian colony. Steele specifically addresses the notion of Australia as a "haunted site ... full of unseen presences."[27]

Notes

- ↑ Symon, Evan V. (14 January 2013). "10 Deleted Chapters that Transformed Famous Books". listverse.com.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (1987). The Secret of Hanging Rock. Australia: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-15550-X.

- ↑ Benson 2005, p. 888.

- ↑ Barrett 1987, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 McCulloch, Janelle (1 April 2017). "The extraordinary story behind Picnic at Hanging Rock". The Age. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ↑ "Hanging out for a mystery". Sydney Morning Herald. 21 January 2007. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ↑ Adams, Phillip. "The great Lindsay mystery". The Australian. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (2014) [1967]. Picnic at Hanging Rock. Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-14-312678-2.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (1998) [1967]. Picnic at Hanging Rock. ISBN 0-09-975061-9.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (2013) [1967]. Picnic at Hanging Rock. ISBN 978-0-09-957714-0.

- ↑ Skidmore & Clark 2014, p. 127.

- ↑ Barrett 1987, p. 85.

- ↑ Edward, Louise (1 April 2017). "Picnic At Hanging Rock: A mystery still unsolved". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ↑ Phipps, Keith. "Picnic At Hanging Rock". The Dissolve. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ Hales, Lydia (31 January 2014). "On this day: Picnic at Hanging Rock airs in the US". Australian Geographic. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ↑ "Isabella Thomson". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Australian National University. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (subject); McKay, Ian (director); Taylor, John (interviewer) (1975). Interview with Joan Lindsay. Refern, NSW: AAV Australia for the Australia Council. Archived from the original (video recording) on 1 January 1988. Retrieved 25 October 2015. (Excerpt available on DailyMotion)

- ↑ Rousseau, Yvonne (1980). The Murders at Hanging Rock. Fitzroy, Australia: Scribe Publications. ISBN 0-908011-02-4.

- 1 2 3 Romensky, Larissa (16 January 2017). "No picnic at Hanging Rock: Campaign to recognise Aboriginal past rather than 'white myth'". ABC. Victoria, Australia. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- 1 2 Webb, Carolyn (26 January 2017). "Replace 'Miranda' myth with Indigenous history at Hanging Rock, says activist". The Age. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ↑ "Picnic at Hanging Rock". Penguin Australia. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (1975) [1967]. Picnic at Hanging Rock. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-003149-2.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (1987) [1967]. Picnic at Hanging Rock. Illustrated Edition. Penguin Australia. ISBN 978-0-670-81828-0.

- ↑ Lindsay, Joan (2013) [1967]. Picnic at Hanging Rock. Penguin Australia. ISBN 978-0-14-356973-2.

- ↑ "The Top 20 must-read Australian novels". Mamamia. 12 January 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ↑ Staff. "10 Aussie books to read before you die". ABC. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- 1 2 Steele 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ Barrett 1987, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Steele 2010, p. 50.

- ↑ Ingram, Tony. "The Day of Saint Valentine". Hanging Rock Recreation Reserve. Archived from the original on 25 December 2008.

- ↑ Horwitz, Jane (30 August 2011). "Backstage: Chatting with Brian MacDevitt, Tony-winning lighting designer". The Washington Post. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ "News". Joe Calarco. Retrieved 29 September 2011.

- ↑ Gans, Andrew (15 April 2009). "Musicals Tales of the City and Picnic at Hanging Rock to Be Developed at O'Neill Theater Center". Playbill. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014.

- ↑ Hetrick, Adam (28 February 2014). "World Premiere of Daniel Zaitchik Musical Picnic at Hanging Rock Debuts in Utah Feb. 28". Playbill. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014.

- ↑ Gow, Keith (3 March 2016). "Malthouse: Picnic at Hanging Rock". Aussie Theatre. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ↑ "Picnic at Hanging Rock 2017". Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "Picnic at Hanging Rock". BBC. 15 Minute Drama. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ "Picnic at Hanging Rock". Radio Listings. 22 October 2015.

- ↑ Frater, Patrick (6 September 2016). "Australian Classic 'Picnic at Hanging Rock' to Be Remade as TV Series". Variety. Retrieved 14 May 2017.

References

- Barrett, Donald (1987). "Picnicking with E.M. Forster, Joan Lindsay et al.". Linq. James Cook University. 5 (1): 79–86.

- Benson, Eugene, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-27885-0.

- Skidmore, Stephanie; Clark, Ian D. (2014). "Hanging Rock Recreation Reserve". An Historical Geography of Tourism in Victoria, Australia: Case Studies. Walter de Gruyter & Co. ISBN 978-3-11-037010-2.

- Steele, Kathleen (2010). "Fear and Loathing in the Australian Bush: Gothic Landscapes in Bush Studies and Picnic at Hanging Rock" (PDF). Colloquy. Monash University. 20.

Further reading

- McCulloch, Janelle (2017). Beyond the Rock. Bonnier Australia. ISBN 978-1-76040-562-5.

External links

| Library resources about Picnic at Hanging Rock (novel) |

Research

- Picnic at Hanging Rock at the National Library of Australia

- Catalog record for Picnic at Hanging Rock at the United States Library of Congress

- Official website of Hanging Rock (Mount Diogenes) in Australia

Theoretical analyses

- "The great Lindsay mystery" by Phillip Adams (The Australian)

- The Solution to Picnic at Hanging Rock? by McKenzie Solutions

Adaptations