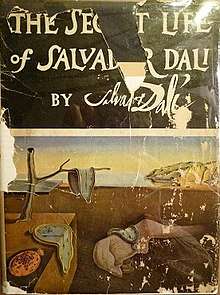

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí

First edition | |

| Author | Salvador Dalí |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | William R. Meinhardt |

| Subject | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Dial Press |

Publication date | 1942 |

The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí is an autobiography by the internationally renowned artist Salvador Dalí published in 1942 by Dial Press. The book was written in French and translated into English by Haakon Chevalier. It covers his family history, his early life, and his early work up through the 1930s, concluding just after Dalí's return to Catholicism and just before the global outbreak of the Second World War. The book is over 400 pages long and contains numerous detailed illustrations.[1] It has attracted both editorial praise[2][3] as well as criticism, notably[4] from George Orwell.[5]

Contents

Dalí opens the book with the statement: "At the age of six I wanted to be a cook. At seven I wanted to be Napoleon. And my ambition has been growing steadily since."[6] According to Time, Dalí wrote with a highly detailed, methodical style that layered words the same way as paint. For example, he states in an early section about his childhood home:

Behind the partly open kitchen door I would hear the scurrying of those bestial women with red hands; I would catch glimpses of their heavy rumps and their hair straggling like manes; and out of the heat and confusion that rose from the conglomeration of sweaty women, scattered grapes, boiling oil, fur plucked from rabbits' armpits, scissors spattered with mayonnaise, kidneys, and the warble of canaries—out of that whole conglomeration the imponderable and inaugural fragrance of the forthcoming meal was wafted to me, mingled with a kind of acrid horse smell.[2]

Dalí states in the book:

- At the age of five years, he encountered an almost dead bat covered with ants and then put it in his mouth, bit it, and then tore the bat almost in half.[2]

- As a young child, he wore a king's ermine cape, a gold scepter, and a crown and then posed for himself with a mirror. He tucked his genitals inside the outfit to look more feminine.[2]

- He stood out dramatically from the poor children in his school by carrying a flexible bamboo cane adorned with a silver dog's head figure and a sailor suit with gold insignia.[2]

- Due to a "refined Jesuitical spirit", he remained a virgin until age 25.[2] As an adolescent, he resisted the sexual advances by his girlfriend for five years until he left her, doing so mostly out of his enjoyment of being in control.[1]

- He became interested in necrophilia, but was then later cured of it.[1]

- While walking down the Boulevard Edgar-Quinet in Paris in 1934, he became so disgusted at the sight of a blind double-amputee that he kicked him.[2]

Reception

Time stated that Dalí's autobiography was "one of the most irresistible books of the year." The magazine called it "a wild jungle of fantasy, posturing, belly laughs, narcissist and sadist confessions", while also commenting that "[t]he question has always been: Is Dalí crazy? The book indicates that Dalí is as crazy as a fox."[2]

Essayist, journalist, and author George Orwell wrote a notable[5][4] criticism of the book titled Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí in 1944. Orwell categorized Dalí's book among other recent autobiographies that he considered "flagrantly dishonest", and he stated that "his autobiography is simply a strip-tease act conducted in pink limelight". He denounced Dalí's accounts of physical abuse against various women in Dalí's early life. He wrote "[i]t is not given to any one person to have all the vices, and Dalí also boasts that he is not homosexual, but otherwise he seems to have as good an outfit of perversions as anyone could wish for" and "[i]f it were possible for a book to give a physical stink off its pages, this one would". He also commented that "[o]ne ought to be able to hold in one's head simultaneously the two facts that Dalí is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being", defending aspects of Dalí's surrealist style.[1]

In July 1999, an article by Charles Stuckey in Art in America stated that Dalí's book "arguably revolutionized a literary genre". He argued that Dalí's book had been intended as slapstick humor and has been generally misinterpreted by critics. He also wrote:

Indebted to the fanciful childhood-oriented writings by artists such as Gauguin, Ernst and de Chirico... Manically boasting about his weaknesses and vices no less than about his achievements and virtues, Dalí helped to initiate today's antiheroic mode of autobiography and, by extension, the sex-centered biographical interpretations of artists and art so prevalent since the 1960s, whether Cézanne and his apples or Johns and his Targets are at issue.[3]

Influences

American writer and humorist James Thurber wrote a semi-autobiographic article for The New Yorker called The Secret Life of James Thurber on February 27, 1943. In the article, Thurber referred to Dalí's title and parts of his style in comparison to his own life. In particular, Thurber noted with dismay that his own autobiographical book, My Life and Hard Times, sold for only $1.75 a copy in 1933 while Dalí's book sold for a full $6.00 in 1942.[7][8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dali. George Orwell Online Library. First published: The Saturday Book for 1944. — GB, London. — 1944. Copy retrieved October 11, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Art: Not So Secret Life". Time. December 28, 1942. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- 1 2 Stuckey, Charles (July 1999). "The Shameful Life of Salvador Dali – Review". Art in America. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

- 1 2 Jim Lindgren (September 28, 2009). "Roman Polanski, George Orwell, and Salvador Dali". The Volokh Conspiracy. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

The first writer I encountered who explored this issue was George Orwell in his essay on Dalí. The essay is also memorable because its second sentence contains one of Orwell’s most resonant ideas

- 1 2 Jonathan Jones. "Why George Orwell was right about Salvador Dalí". The Guardian. Retrieved October 11, 2009.

George Orwell isn't usually thought of as an art critic... But his contribution to the literature of modern art is also worth celebrating. In 1944 Orwell wrote an essay called Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí.

- ↑ Salvador Dalí (1993). The secret life of Salvador Dalí. Courier Dover Publications. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-486-27454-6.

- ↑ JAMES THURBER AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION Archived April 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ James Thurber. “The Secret Life of James Thurber”. The New Yorker, February 27, 1943, p. 15