The Races of Europe (Ripley)

William Z. Ripley published in 1899 The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study, which grew out of a series of lectures he gave at the Lowell Institute at Columbia in 1896. Ripley believed that race was critical to understanding human history, though his work afforded environmental and non-biological factors, such as traditions, a strong weight as well. He believed, as he wrote in the introduction to The Races of Europe, that:

- "Race, properly speaking, is responsible only for those peculiarities, mental or bodily, which are transmitted with constancy along the lines of direct physical descent from father to son. Many mental traits, aptitudes, or proclivities, on the other hand, which reappear persistently in successive populations may be derived from an entirely different source. They may have descended collaterally, along the lines of purely mental suggestion by virtue of mere social contact with preceding generations."[1]

While not substantiating this claim Ripley writes on page 119 that a child's eye color favors the eye color of the father and writes regarding the overall influence of paternal descent:

- "One law alone, to which we have already made reference, seems to be verified. It is this; viz., that types, which are combinations of separate traits, are rarely if ever stable in a single line through several generations. The physical characteristics are transmitted in independence of one another in nine cases out of ten. The absolute necessity of studying men in large masses, in order to counteract this tendency is by this fact rendered imperative."[2]

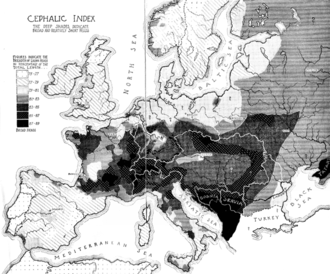

Ripley's book, written to help finance his children's education, became very well respected in anthropology, renowned for its careful writing and careful compilation (and criticism) of the data of many other anthropologists in Europe and the United States. Ripley based his conclusions about race by correlating anthropometric data with geographical data, paying special attention to the use of the cephalic index, which at the time was considered a well-established measure. From this and other socio-geographical factors, Ripley classified Europeans into three distinct races:

- Teutonic – members of the northern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), tall in stature, and possessed pale hair, eyes and skin.

- Mediterranean – members of the southern race were long-skulled (or dolichocephalic), short/medium in stature, and possessed dark hair, eyes and skin.

- Alpine – members of the central race were round-skulled (or brachycephalic), stocky in stature, and possessed intermediate hair, eye and skin color.

Ripley's tripartite system of race put him at odds both with others on the topic of human difference, including those who insisted that there was only one European race, and those who insisted that there were at least ten European races (such as Joseph Deniker, whom Ripley saw as his chief rival). The conflict between Ripley and Deniker was criticized by Jan Czekanowski, who states that "the great discrepancies between their claims decrease the authority of anthropology", and what is more, he points out that both Deniker and Ripley had one common feature, as they both omitted the existence of an Armenoid race, which Czekanowski claimed to be one of the four main races of Europe, met especially among the Eastern and Southern Europeans.[3] Ripley was the first American recipient of the Huxley Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1908 on account of his contributions to anthropology.

The Races of Europe, overall, became an influential book of the Progressive Era in the field of racial taxonomy.[4] Ripley's tripartite system was especially championed by Madison Grant, who changed Ripley's "Teutonic" type into Grant's own Nordic type (taking the name, but little else, from Deniker), which he postulated as a master race.[5] It is in this light that Ripley's work on race is usually remembered today, though little of Grant's ideology is present in Ripley's original work. In 1933, the Harvard anthropologist Carleton S. Coon was invited to write a new edition of Ripley's 1899 book, which Coon dedicated to Ripley. Coon's entirely rewritten version of the book was published in 1939.

See also

References

- ↑ William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1899), p. 1.

- ↑ William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1899), p. 120.

- ↑ Czekanowski, Jan (1934). Człowiek w Czasie i Przestrzeni (eng. A Human in Time and Space) - The lexicon of biological anthropology. Kraków, Poland: Trzaska, Ewert i Michalski - Bibljoteka Wiedzy.

- ↑ Thomas C. Leonard, "'More Merciful and Not Less Effective': Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era" Historical of Political Economy 35:4 (2003): 687–712, discussion of Ripley's work on p. 690. Available online at http://www.princeton.edu/~sbwhite/eugenicsC.pdf.

- ↑ Matthew Press Guterl, The Color of Race in America, 1900-1940 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), and Jonathan P. Spiro, "Patrician racist: The evolution of Madison Grant" (Ph.D dissertation, Dept. of History, University of California, Berkeley, 2000).

External links

- The Races of Europe: A Sociological Study (1899) by William Zebina Ripley at the Internet Archive