The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

| The Piper at the Gates of Dawn | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by Pink Floyd | ||||

| Released | 5 August 1967 | |||

| Recorded | 21 February – 21 May 1967 | |||

| Studio | EMI Studios, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 41:51 | |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | Norman Smith | |||

| Pink Floyd chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Piper at the Gates of Dawn | ||||

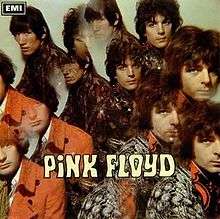

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn is the debut studio album by the English rock band Pink Floyd, and the only one made under founding member Syd Barrett's leadership. The album, named after the title of chapter seven of Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows[3] and featuring a kaleidoscopic cover photo of the band taken by Vic Singh, was recorded from February to May 1967 and released on 5 August 1967. It was produced by Beatles engineer Norman Smith and released in 1967 by EMI Columbia in the United Kingdom and Tower in the United States, in August and October respectively.

The release of the album in the US was timed with the band's tour of the US. In the UK, no singles were released from the album, but in the US "Flaming" was offered as a single. The US version of the album has a rearranged track list, and contains the UK non-album single, "See Emily Play". Two of the album's songs, "Astronomy Domine" and "Interstellar Overdrive", became long-term mainstays of the band's live set list, while other songs were performed live only a handful of times.

Since its release, the album has been hailed as one of the best psychedelic rock albums. In 1973, it was packaged with the band's second album, A Saucerful of Secrets, and released as A Nice Pair to introduce new fans to the band's early work after the success of The Dark Side of the Moon. Special limited editions of The Piper at the Gates of Dawn were issued to mark its thirtieth and fortieth anniversaries in 1997 and 2007, respectively, with the latter release containing bonus tracks. In 2012, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn was voted 347th on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Albums of All Time".

Background

Architecture students Roger Waters, Nick Mason and Richard Wright and art student Syd Barrett had performed under various group names since 1962, and began touring as "The Pink Floyd Sound" in 1965.[4] They turned professional on 1 February 1967 when they signed with EMI, with an advance fee of £5,000.[5][6][7] Their first single, a song about a kleptomaniac transvestite titled "Arnold Layne", was released on 11 March to mild controversy, as Radio London refused to air it.[5][8]

About three weeks later, the band were introduced to the mainstream media.[nb 1] EMI's press release claimed that the band were "musical spokesmen for a new movement which involves experimentation in all the arts", but EMI attempted to put some distance between them and the underground scene from which the band originated by stating that "the Pink Floyd does not know what people mean by psychedelic pop and are not trying to create hallucinatory effects on their audiences."[9][10] The band returned to Sound Techniques studio to record their next single, "See Emily Play", on 18 May.[11][12] The single was released almost a month later, on 16 June, and reached number six in the charts.[13][14]

Pink Floyd picked up a tabloid reputation for making music for LSD users. The popular broadsheet News of the World printed a story nine days before the album's recording sessions began, saying that "The Pink Floyd group specialise in 'psychedelic music', which is designed to illustrate LSD experiences."[15] Contrary to this image, only Barrett was known to be taking LSD; authors Ray B. Browne and Pat Browne contend that he was the "only real drug user in the band".[16]

Recording

The band's record deal was relatively poor for the time: a £5,000 advance over five years, low royalties and no free studio time. However, it did include album development, and EMI, unsure of exactly what kind of band they had signed, gave them free rein to record whatever they wanted.[17]

They were obliged to record their first album at EMI's Abbey Road Studios in London,[10][18] overseen by producer Norman Smith,[10][19] a central figure in Pink Floyd's negotiations with EMI.[20] Balance engineer Pete Bown, who had mentored Smith, helped ensure that the album had a unique sound, through his experimentation with equipment and recording techniques.[21] Bown, assisted by studio manager David Harris, set up microphones an hour before the sessions began. Bown's microphone choices were mostly different from those used by Smith to record the Beatles' EMI sessions.[22] Because of Barrett's quiet voice, he was placed in a vocal isolation booth to sing his parts.[22] Automatic double tracking (ADT) was used to add layers of echo to the vocals and to some instruments.[23] The album featured an unusually heavy use of echo and reverberation to give it its own unique sound. Much of the reverberation effect came from a set of Elektro-Mess-Technik plate reverberators – customised EMT 140s containing thin metal plates under tension – and the studio's tiled echo chamber built in 1931.[23][24]

The album is made up of two different classes of songs: lengthy improvisations from the band's live performances and shorter songs that Barrett had written.[25] Barrett's LSD intake escalated part-way through the album's recording sessions.[26] Although in his 2005 autobiography Mason recalled the sessions as relatively trouble-free, Smith disagreed and claimed that Barrett was unresponsive to his suggestions and constructive criticism.[27][28] In an attempt to build a relationship with the band, Smith played jazz on the piano while the band joined in. These jam sessions worked well with Waters, who was apparently helpful, and Wright, who was "laid-back". Smith's attempts to connect with Barrett were less productive: "With Syd, I eventually realised I was wasting my time."[29] Smith later admitted that his traditional ideas of music were somewhat at odds with the psychedelic background from which Pink Floyd had come. Nevertheless, he managed to "discourage the live ramble", as band manager Peter Jenner called it, guiding the band toward producing songs with a more manageable length.[10][30]

Barrett would end up writing eight of the album's songs and contributing to two instrumentals credited to the whole band, with Waters creating the sole remaining composition "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk".[31] Mason recalled how the album "was recorded in what one might call the old-fashioned way: rather quickly. As time went by we started spending longer and longer."[32]

Abbey Road engineer Pete Bown describing his introduction to "Interstellar Overdrive" [33]

Recording started on 21 February[34] with six takes[35] of "Matilda Mother", then called "Matilda's Mother".[25][36] The following week, on the 27th,[37] the band recorded five takes of "Interstellar Overdrive",[nb 2][nb 3][39] and "Chapter 24".[37][40] On 16 March, the band had another go at recording "Interstellar Overdrive", in an attempt to create a shorter version,[41] and "Flaming" (originally titled "Snowing"), which was recorded in a single take[42] with one vocal overdub.[24] On 19 March, six takes of "The Gnome" were recorded.[24][43] The following day, the band recorded Waters' "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk".[43][44] On 21 March, the band were invited to watch the Beatles record "Lovely Rita".[45][46] The following day, they recorded "The Scarecrow" in one take.[47][48] The next three tracks - "Astronomy Domine",[nb 4] "Interstellar Overdrive" and "Pow R. Toc H." – were worked on extensively between 21 March and 12 April,[51] having originally been lengthy instrumentals.[49] Between 12 and 18 April,[52] the band recorded "Percy the Rat Catcher"[nb 5] and a currently unreleased track called "She Was a Millionaire".[55][56][57]

"Percy the Rat Catcher" received overdubs across five studio sessions and then was mixed in late June, eventually being given the name "Lucifer Sam".[32] Songwriting for the majority of the album is credited solely to Barrett, with tracks such as "Bike" having been written in late 1966 before the album was started.[25][58][59] "Bike" was recorded on 21 May 1967 and originally entitled "The Bike Song".[25] By June, Barrett's increasing LSD use during the recording project left him looking visibly debilitated.[26]

Release

In June 1967 before the album was released, the single "See Emily Play" was sold as a 7-inch 45 rpm record, with "The Scarecrow" on the B-side, listed as "Scarecrow".[60] The full album was released on 5 August 1967, including "The Scarecrow".

Pink Floyd continued to perform at the UFO Club, drawing huge crowds, but Barrett's deterioration caused them serious concern. The band initially hoped that his erratic behavior was a phase that would pass, but others, including manager Peter Jenner and his secretary June Child,[nb 6] were more realistic:

... I found him in the dressing room and he was so ... gone. Roger Waters and I got him on his feet, we got him out to the stage ... and of course the audience went spare because they loved him. The band started to play and Syd just stood there. He had his guitar around his neck and his arms just hanging down.[62]

To the band's consternation, they were forced to cancel their appearance at the prestigious National Jazz and Blues Festival, informing the music press that Barrett was suffering from nervous exhaustion. Jenner and Waters arranged for Barrett to see a psychiatrist – a meeting he did not attend. He was sent to relax in the sun on the Spanish island of Formentera with Waters and Sam Hutt (a doctor well-established in the underground music scene), but this led to no visible improvement.[63][64][65][66]

The original UK LP (with a monaural mix)[nb 7] was released on 5 August 1967, and one month later it was released in stereophonic mix.[nb 8] It reached number six on the UK charts.[14][69][70] The Canadian LP[nb 9] had the same title and track listing as the UK version. The original US album appeared on the Tower division of Capitol on 26 October 1967. This version[nb 10][nb 11] was officially titled simply Pink Floyd, though the original album title did appear on the back cover as on the UK issue, and Dick Clark referred to the record by its original title when the group appeared on his American Bandstand television program on 18 November 1967.[74][75] The US album featured an abbreviated track listing,[76] and reached number 131 on the Billboard charts. The UK single, "See Emily Play", was substituted for "Astronomy Domine", "Flaming" and "Bike".[76] Released in time for the band's US tour, "Flaming" was released as a single, backed with "The Gnome".[77] The Tower issue of the album also faded out "Interstellar Overdrive" and broke up the segue into "The Gnome" to fit the re-sequencing of the songs. Later US issues on compact disc had the same title and track list as the UK version. The album was certified Gold in the US on 11 March 1994.[69]

About being handled on Tower Records, Jenner commented that: "In terms of the U.K. and Europe it was always fine. America was always difficult. Capitol couldn't see it. You know, 'What is this latest bit of rubbish from England? Oh Christ, it'll give us more grief, so we'll put it out on Tower Records', which was a subsidiary of Capitol Records [...] It was a very cheapskate operation and it was the beginning of endless problems The Floyd had with Capitol. It started off bad and went on being bad."[78]

Packaging

Vic Singh[79]

Up-and-coming society photographer Vic Singh was hired to photograph the band for the album cover. Singh shared a studio with photographer David Bailey, and he was friends with Beatles guitarist George Harrison. Singh asked Jenner and King to dress the band in the brightest clothes they could find. Vic Singh then shot them with a prism lens that Harrison had given him.[79] The cover was meant to resemble an LSD trip, a style that was favoured at the time.[80]

Barrett came up with the album title The Piper at the Gates of Dawn; the album was originally titled Projection up to as late as July 1967.[81] The title was taken from that of chapter seven of Kenneth Grahame's The Wind in the Willows[82][83] which contains a visionary encounter with the god Pan, who plays his pan pipe at dawn.[84] It was one of Barrett's favourite books, and he often gave friends the impression that he was the embodiment of Pan.[nb 12][31][86] The moniker was later used in the song "Shine On You Crazy Diamond", in which Barrett is called "you Piper".[87] The cover for the album was one of several Pink Floyd album covers used on a series of Royal Mail stamps issued in May 2016 to commemorate 50 years of Pink Floyd.[88]

Reception

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| About.com | |

| AllMusic | |

| The Daily Telegraph | |

| MusicHound | 3.5/5[92] |

| NME | 9/10[93] |

| Paste | 9.5/10[94] |

| Pitchfork | 9.4/10[95] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

At the time of release, both Record Mirror and NME gave the album four stars out of five. Record Mirror commented that "[t]he psychedelic image of the group really comes to life, record wise, on this LP which is a fine showcase for both their talent and the recording technique. Plenty of mind blowing sound, both blatant and subtle here, and the whole thing is extremely well performed."[98] Cash Box called it "a particularly striking collection of driving, up-to-date rock ventures".[99] Paul McCartney[45] and Pink Floyd's past producer Joe Boyd both rated the album highly. Some voiced the opinion of the underground fans, by suggesting that the album did not reflect the band's live performances.[12]

In recent years, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn has gained even more recognition. The album is hailed not only as a psychedelic masterpiece but LSD is named as a direct influence.[100] In 1999, Rolling Stone magazine gave the album 4.5 stars out of 5, calling it "the golden achievement of Syd Barrett". Q magazine described the album as "indispensable" and included it in their list of the best psychedelic albums ever. It was also ranked 40th in Mojo magazine's "The 50 Most Out There Albums of All Time" list. In 2000, Q magazine placed The Piper at the Gates of Dawn at number 55 in its list of the 100 greatest British albums ever. In 2012, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn was voted 347th on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the 500 greatest albums ever.[101]

James E. Perone says that Piper became known as a concept album in later years, because listeners wanted to play it all the way through rather than pick out a favourite song.[102] While Beatles biographer Philip Norman agrees that Piper is a concept album,[103] other authors contend that Pink Floyd did not start making concept albums until 1973's The Dark Side of the Moon. Author George Reisch called Pink Floyd the "undisputed" kings of the concept album, but only starting from Dark Side.[104] In July 2006, Billboard described The Piper at the Gates of Dawn as "one of the best psychedelic rock albums ever, driven by Barrett's oddball narratives and the band's skill with both long jams and perfect pop nuggets".[1]

Reissues

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn was reissued in the UK in 1979 as a stereo vinyl album,[nb 13] and on CD in the UK and US in 1985.[nb 14] A digitally remastered stereo CD, with new artwork, was released in the US in 1994,[nb 15] and in 1997 limited edition 30th anniversary mono editions were released in the UK, on CD and vinyl.[nb 16] These limited editions were in a hefty digipak with 3-D box art for continental Europe and the world outside the United States. This mono CD included a slightly edited version of "Flaming". A six-track bonus CD, 1967: The First Three Singles, was given away alongside the 1997 30th-anniversary edition of the album.

In 1973, the album, along with A Saucerful of Secrets, was released as a two-disc set on Capitol/EMI's Harvest Records label, titled A Nice Pair[nb 17][nb 18] to introduce fans to the band's early work after the success of The Dark Side of the Moon. (On the American version of that compilation, the original four-minute studio version of "Astronomy Domine" was replaced with the eight-minute live version found on Ummagumma.) The American edition of A Nice Pair also failed to properly restore the segue between "Interstellar Overdrive" and "The Gnome".

For the 40th anniversary, a two-disc edition[nb 19] was released on 4 September 2007, and a three-disc set[nb 20] was released on 11 September 2007. The packaging – designed by Storm Thorgerson – resembles a cloth-covered book, along with a twelve-page reproduction of a Syd Barrett notebook. Discs one and two contain the full album in its original mono mix (disc one), as well as the alternative stereo version (disc two). Both have been newly remastered by James Guthrie. The third disc includes several Piper-era outtakes from the Abbey Road vaults, along with the band's first three mono singles. Unreleased material includes an alternative, shorter take of "Interstellar Overdrive" that was previously thought lost, the pre-overdubbed abridged mix of "Interstellar Overdrive" previously only available on an EP in France, an alternative mix of "Matilda Mother" as it appeared early in the sessions and also the 1967 stereo mix of "Apples and Oranges", which features extra untrimmed material at the beginning and end.

Piper was remastered and re-released on 26 September 2011 as part of the Why Pink Floyd...? reissue campaign. It is available in this format as either a stand-alone album,[nb 21][nb 22] or as part of the Why Pink Floyd ... ? Discovery box set,[nb 23][nb 24] along with the 13 other studio albums and a new colour booklet. Then the album was re-released on the band's own Pink Floyd Records label in 3 June 2016 for the world outside Europe.

Live performances

Although there was never an official tour of the album, the band gigged in the UK to promote the album. They played dates in Ireland and Scandinavia, and in late October the band was to embark on their first tour of the United States. It was unsuccessful, mainly because of the mental breakdown of Barrett.[63] In his capacity as tour manager, Andrew King traveled to New York to begin preparations, but he ran into serious problems. Visas had not arrived, prompting the cancellation of the first six dates.[64] The band finally flew across the Atlantic on 1 November, but work permits were not yet obtained, so they settled into a hotel in Sausalito, California, just north of San Francisco.[113] After a number of cancellations, the first US performance was given 4 November at Winterland Ballroom, following Janis Joplin fronting Big Brother and the Holding Company.[113]

For the American tour, many numbers such as "Flaming" and "The Gnome" were dropped, while others such as "Astronomy Domine" and "Interstellar Overdrive" remained, and were central to the band's set list during this period, often performed as encores until around 1971.[114] "Astronomy Domine" was later included on the live disc of Ummagumma,[115][116] and adopted by the post-Waters Pink Floyd during the 1994 Division Bell tour, with a version included on the 1995 live album Pulse. David Gilmour, though not a member of Pink Floyd at the time the song was originally recorded, resurrected "Astronomy Domine" for his On an Island and Rattle That Lock tours.

Communication between company and band was almost non-existent, and Pink Floyd's relationship with Tower and Capitol was therefore poor. Barrett's mental condition mirrored the problems that King encountered;[65] when the band performed at Winterland, he detuned his guitar during "Interstellar Overdrive" until the strings fell off. His odd behaviour grew worse in subsequent performances, and during a television recording for The Pat Boone Show he confounded the director by lip-syncing "Apples and Oranges" perfectly during the rehearsal, and then standing motionless during the take. King quickly curtailed the band's US visit, sending them home on the next flight.[66]

Shortly after their return from the US, beginning 14 November, the band supported Jimi Hendrix on a tour of England,[66] but on one occasion Barrett failed to turn up and they were forced to replace him with singer/guitarist David O'List borrowed from the opening band the Nice.[63] Barrett's depression worsened the longer the tour continued.[117] Longtime Pink Floyd psychedelic lighting designer Peter Wynne-Willson left at the end of the Hendrix tour, though he sympathized with Barrett, whose position as frontman was increasingly insecure. Wynne-Willson, who had worked for a percentage, was replaced by his assistant John Marsh who collected a lesser wage.[118] Pink Floyd released "Apples and Oranges" (recorded prior to the US tour on 26 and 27 October),[119] but for the rest of the band, Barrett's condition had reached a crisis point, and they responded by adding David Gilmour to their line-up, initially to cover for Syd's lapses during live performances.[63]

Tracks 8–11 on the UK album edition were played the least during live performances.[120] The success of "See Emily Play" and "Arnold Layne" meant that the band was forced to perform some of their singles for a limited period in 1967, but they were eventually dropped after Barrett left the band. "Flaming" and "Pow R. Toc H." were also played regularly by the post-Barrett Pink Floyd in 1968, even though these songs were in complete contrast to the band's other works at this time. Some of the songs from Piper would be reworked and rearranged for The Man and The Journey live show in 1969 ("The Pink Jungle" was taken from "Pow R. Toc H.", and part of "Interstellar Overdrive" was used for "The Labyrinths of Auximines").

Beginning in September 1967, the band played several new compositions. These included "One in a Million", "Scream Thy Last Scream", "Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun" and "Reaction in G", the last of which was a song created by the band in response to crowds asking for their hit singles "See Emily Play" and "Arnold Layne".[121]

Barrett resurrected the track "Lucifer Sam" with his short-lived 1972 band Stars[122]

Track listing

All songs written and composed by Syd Barrett, except where noted.

UK release

| Side one | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | "Astronomy Domine" | Barrett, Richard Wright | 4:12 |

| 2. | "Lucifer Sam" | Barrett | 3:07 |

| 3. | "Matilda Mother" | Wright, Barrett | 3:08 |

| 4. | "Flaming" | Barrett | 2:46 |

| 5. | "Pow R. Toc H." (Barrett, Roger Waters, Wright, Nick Mason) | Instrumental, wordless vocals by Barrett, Waters | 4:26 |

| 6. | "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk" (Waters) | Waters | 3:05 |

| Total length: | 20:44 | ||

| Side two | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | "Interstellar Overdrive" (Barrett, Waters, Wright, Mason) | Instrumental | 9:41 |

| 2. | "The Gnome" | Barrett | 2:13 |

| 3. | "Chapter 24" | Barrett | 3:42 |

| 4. | "The Scarecrow" | Barrett | 2:11 |

| 5. | "Bike" | Barrett | 3:21 |

| Total length: | 21:08 | ||

US release

| Side one | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | "See Emily Play" | Barrett | 2:53 |

| 2. | "Pow R. Toc H." (Barrett, Waters, Wright, Mason) | Instrumental, wordless vocals by Barrett, Waters | 4:26 |

| 3. | "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk" (Waters) | Waters | 3:05 |

| 4. | "Lucifer Sam" | Barrett | 3:07 |

| 5. | "Matilda Mother" | Wright, Barrett | 3:08 |

| Side two | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | "The Scarecrow" | Barrett | 2:11 |

| 2. | "The Gnome" | Barrett | 2:13 |

| 3. | "Chapter 24" | Barrett | 3:42 |

| 4. | "Interstellar Overdrive" (Barrett, Waters, Wright, Mason) | Instrumental | 9:41 |

40th anniversary edition

| Disc one | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | "Astronomy Domine (Mono)" | Barrett, Wright | 4:17 |

| 2. | "Lucifer Sam (Mono)" | Barrett | 3:09 |

| 3. | "Matilda Mother (Mono)" | Wright, Barrett | 3:05 |

| 4. | "Flaming (Mono)" | Barrett | 2:46 |

| 5. | "Pow R. Toc H. (Mono)" (Barrett, Roger Waters, Wright, Nick Mason) | Instrumental, wordless vocals by Barrett, Waters | 4:24 |

| 6. | "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk (Mono)" (Waters) | Waters | 3:07 |

| 7. | "Interstellar Overdrive (Mono)" (Barrett, Waters, Wright, Mason) | Instrumental | 9:41 |

| 8. | "The Gnome (Mono)" | Barrett | 2:14 |

| 9. | "Chapter 24 (Mono)" | Barrett | 3:53 |

| 10. | "The Scarecrow (Mono)" | Barrett | 2:10 |

| 11. | "Bike (Mono)" | Barrett | 3:27 |

| Disc two | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | "Astronomy Domine (Stereo)" | Barrett, Wright | 4:14 |

| 2. | "Lucifer Sam (Stereo)" | Barrett | 3:07 |

| 3. | "Matilda Mother (Stereo)" | Wright, Barrett | 3:08 |

| 4. | "Flaming (Stereo)" | Barrett | 2:46 |

| 5. | "Pow R. Toc H. (Stereo)" (Barrett, Roger Waters, Wright, Nick Mason) | Instrumental, wordless vocals by Barrett, Waters | 4:26 |

| 6. | "Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk (Stereo)" (Waters) | Waters | 3:06 |

| 7. | "Interstellar Overdrive (Stereo)" (Barrett, Waters, Wright, Mason) | Instrumental | 9:40 |

| 8. | "The Gnome (Stereo)" | Barrett | 2:13 |

| 9. | "Chapter 24 (Stereo)" | Barrett | 3:42 |

| 10. | "The Scarecrow (Stereo)" | Barrett | 2:11 |

| 11. | "Bike (Stereo)" | Barrett | 3:24 |

| Disc three | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | "Arnold Layne" | Barrett | 2:57 |

| 2. | "Candy and a Currant Bun" | Barrett | 2:45 |

| 3. | "See Emily Play" | Barrett | 2:54 |

| 4. | "Apples and Oranges" | Barrett | 3:05 |

| 5. | "Paintbox" (Wright) | Wright | 3:45 |

| 6. | "Interstellar Overdrive (Take 2) (French Edit)" | Instrumental | 5:15 |

| 7. | "Apples and Oranges (Stereo Version)" | Barrett | 3:11 |

| 8. | "Matilda Mother (Alternative Version)" | Barrett | 3:09 |

| 9. | "Interstellar Overdrive (Take 6)" | Instrumental | 5:03 |

Personnel

Pink Floyd[123]

- Syd Barrett – lead guitar, vocals

- Roger Waters – bass guitar, vocals

- Richard Wright – Farfisa Combo Compact organ, piano, celesta (uncredited), vocals (uncredited)

- Nick Mason – drums, percussion

Production

- Syd Barrett – rear cover design

- Peter Bown – engineering

- Peter Jenner – intro vocalisations on "Astronomy Domine" (uncredited)[124]

- Vic Singh – front cover photography

- Norman Smith – production, vocal and instrumental arrangements, drum roll on "Interstellar Overdrive"[125]

Charts and certifications

Charts

|

Certifications

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

Footnotes

- ↑ They were already well known in the underground scene.

- ↑ This was not the first time the band had recorded the song as it had been recorded earlier in the year at Sound Techniques Studios in London, between 11 and 12 January, for producer Peter Whitehead's documentary Tonite Lets All Make Love in London.

- ↑ An early, unoverdubbed, shortened mix of the album's "Interstellar Overdrive" was used for a French EP release that July.[38][39]

- ↑ 14 takes of "Astronomy Domine" were recorded,[49] over a seven-hour session.[50]

- ↑ "Percy the Rat Catcher"."[53][54]

- ↑ Child was employed by Peter Jenner as a secretary and general production assistant.[61]

- ↑ UK EMI Columbia SX 6157[67]

- ↑ UK EMI Columbia SCX 6157[68]

- ↑ Canada Capitol ST-6242[71]

- ↑ US Capitol Tower T-5093[72]

- ↑ US Capitol Tower ST 5093[73] Original US stereo LP

- ↑ Barrett believed he had a dream-like experience meeting Pan, with characters from the book. Andrew King said Barrett thought Pan had given him understanding of how nature works.[37][85]

- ↑ UK EMI Fame FA 3065[69]

- ↑ UK EMI CDP 7463842, US Capitol CDP 7463842[69]

- ↑ US Capitol CDP 7463844[69]

- ↑ UK EMI LP EMP 1110, EMI CD EMP 1110[69]

- ↑ UK EMI Harvest SHDW 403[105]

- ↑ US Capitol Harvest SABB-11257[106] Original A Nice Pair US LP

- ↑ Europe EMI 503 9232[107]

- ↑ Europe EMI 50999 5 03919 2 9[108]

- ↑ Europe EMI 50999 028935 2 5[109] 2011 remaster Europe CD

- ↑ US Capitol 50999 028935 2 5[110]

- ↑ Europe EMI 50999 0 82613 2 8[111]

- ↑ US Capitol 0082613[112]

Citations

- 1 2 "Pink Floyd Co-Founder Syd Barrett Dies at 60". Billboard. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- ↑ Rob Young (10 May 2011). Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain's Visionary Music. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 454–. ISBN 978-1-4299-6589-7.

- ↑ Cavanagh, John (2003). The Piper at the Gates of Dawn. New York [u.a.]: Continuum. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8264-1497-7.

- ↑ Povey, Glenn (2007). Echoes: The Complete History of Pink Floyd (New ed.). Mind Head Publishing. pp. 24–29. ISBN 978-0-9554624-0-5.

- 1 2 Schaffner, Nicholas (2005). Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey (New ed.). London: Helter Skelter. pp. 54–56. ISBN 1-905139-09-8.

- ↑ Blake, Mark (2008). Comfortably Numb: The Inside Story of Pink Floyd. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo. p. 74. ISBN 0-306-81752-7.

- ↑ Chapman, Rob (2010). Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head (Paperback ed.). London: Faber. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-571-23855-2.

- ↑ Cavanagh 2003, p. 19

- ↑ Schaffner 2005, p. 57

- 1 2 3 4 Manning, Toby (2006). The Rough Guide to Pink Floyd (1st ed.). London: Rough Guides. p. 34. ISBN 1-84353-575-0.

- ↑ Schaffner 2005, p. 66

- 1 2 Chapman 2010, p. 171

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 88–89

- 1 2 "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". officialcharts.com. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Cavanagh 2003, p. 42

- ↑ Browne, Ray B.; Browne, Pat (2000). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. p. 610. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- ↑ Povey 2007, pp. 37–39

- ↑ Schaffner 2005, p. 55

- ↑ Chapman 2010, pp. 169–170

- ↑ Mason, Nick (2011) [2004]. "Freak Out Schmeak Out". In Philip Dodd. Inside Out – A Personal History of Pink Floyd (Paperback ed.). Phoenix. pp. 70, 87. ISBN 978-0-7538-1906-7.

- ↑ Palacios, Julian (2010). Syd Barrett & Pink Floyd: Dark Globe (Rev. ed.). London: Plexus. pp. 180–182. ISBN 0-85965-431-1.

- 1 2 Palacios 2010, p. 182

- 1 2 Palacios 2010, p. 183

- 1 2 3 Palacios 2010, p. 196

- 1 2 3 4 Chapman 2010, p. 142

- 1 2 Jeffrey, Laura S. (2010). Pink Floyd: The Rock Band. Berkeley Heights, NJ: Enslow Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7660-3030-5.

- ↑ Mason 2011, pp. 92–93

- ↑ Palacios 2010, pp. 183–184

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 77

- ↑ Blake 2008, pp. 84–85

- 1 2 Perna, Alan di; Tolinski, Brad (2002). Kitts, Jeff, ed. Guitar World Presents Pink Floyd (1st ed.). Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-634-03286-8.

- 1 2 Cavanagh 2003, p. 39

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 85

- ↑ Jones, Malcolm (2003). The Making of The Madcap Laughs (21st Anniversary ed.). Brain Damage. p. 28.

- ↑ Palacios 2010, p. 185

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 149

- 1 2 3 Palacios 2010, p. 187

- ↑ "The Pink Floyd – Arnold Layne (Vinyl) at Discogs". Discogs. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- 1 2 Palacios 2010, p. 188

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 151

- ↑ Palacios 2010, p. 195

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 152

- 1 2 Chapman 2010, p. 153

- ↑ Palacios 2010, p. 198

- 1 2 Manning 2006, p. 36

- ↑ Palacios 2010, pp. 198–199

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 154

- ↑ Palacios 2010, p. 199

- 1 2 Chapman 2010, p. 155

- ↑ Palacios 2010, p. 206

- ↑ Palacios 2010, pp. 198, 206

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 158

- ↑ Jones 2003, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Cavanagh 2003, pp. 37–38

- ↑ Palacios 2010, p. 209

- ↑ Palacios 2010, p. 371

- ↑ "Unreleased Pink Floyd material: Millionaire / She Was a Millionaire". Pinkfloydhyperbase.dk. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ↑ Manning 2006, p. 29

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 162

- ↑ Ruhlmann, William. "The Scarecrow – Pink Floyd". =Allmusic.com. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ Schaffner 2005, p. 36

- ↑ Mason 2011, p. 95

- 1 2 3 4 Mason 2011, pp. 95–105

- 1 2 Blake 2008, p. 94

- 1 2 Schaffner 2005, pp. 88–90

- 1 2 3 Schaffner 2005, pp. 91–92

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. Original UK mono LP

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. Original UK stereo LP

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Povey 2007, p. 342

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 172

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. Original Canadian stereo LP

- ↑ "The Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. Original US mono LP

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ↑ "Pink Floyd Performs on US Television for the First Time: American Bandstand, 1967". Open Culture. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- ↑ Dolloff, Matt. "Watch Pink Floyd Perform with Syd Barrett on "American Bandstand" in 1967". WZLX Radio. Retrieved 4 November 2016.

- 1 2 Cavanagh 2003, pp. 54–55

- ↑ Cavanagh 2003, p. 55

- ↑ Cavanagh 2003, pp. 55–56

- 1 2 Blake 2008, p. 92

- ↑ Carruthers, Bob (2011). Pink Floyd - Uncensored on the Record. Coda Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-908538-27-7.

- ↑ Chapman 2010, pp. 148–149

- ↑ Cavanagh 2003, pp. 2–3

- ↑ Vegro, Symon (2009). All That You Touch. AuthorHouse. p. 78. ISBN 9781467897969.

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 148

- ↑ Young, Rob (2011). Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain's Visionary Music. Faber & Faber. pp. 454–455. ISBN 978-1-4299-6589-7.

- ↑ Reisch, George A. (2007). Pink Floyd and Philosophy: Careful with That Axiom, Eugene! (3. print. ed.). Chicago: Open Court. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-8126-9636-3.

It started with a guy named Syd who styled himself a 'Piper at the Gates of Dawn' and spent most of the 1960s surrounded by groupies.

- ↑ "Syd Barrett: Roger 'Syd' Barrett, leader of Pink Floyd, died on July 7th, aged 60". The Economist. 380. Economist Newspaper Ltd. 20 July 2006. p. 83. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- ↑ "Royal Mail unveils stamps to mark 50 years of Pink Floyd". BBC news. 26 May 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ↑ White, Dave. "Pink Floyd – Review of 40th Anniversary Edition of Piper at the Gates of Dawn by Pink Floyd". About.com. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Huey, Steve. "The Piper at the Gates of Dawn – Pink Floyd: Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards: AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ McCormick, Neil (20 May 2014). "Pink Floyd's 14 studio albums rated". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (eds) (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 872. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ↑ "NME Album Reviews – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn – nme.com". nme.com. 4 September 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Deusner, Stephen (28 September 2011). "Pink Floyd: Piper at the Gates of Dawn ("Why Pink Floyd?" Reissue) :: Music :: Reviews :: Paste". pastemagazine.com. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ Klein, Joshua (18 September 2007). "Pink Floyd: The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (40th Anniversary Edition) | Album Reviews | Pitchfork". Pitchfork. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ "Review: The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". Q: 275. January 1995.

- ↑ Sheffield, Rob (2 November 2004). "Pink Floyd: Album Guide". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media, Fireside Books. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ McAlwane, Jim. "August 1967". Marmalade Skies. Archived from the original on 15 January 2007. Retrieved 7 May 2017. Review originally published in Record Mirror in August 1967, no author cited.

- ↑ Povey 2007, p. 66

- ↑ MacDonald, edited by Bruno (1996). Pink Floyd: Through the Eyes of – the Band, its Fans, Friends, and Foes. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-306-80780-0.

- ↑ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time: Pink Floyd, 'The Piper at the Gates of Dawn' | Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Perone, James E. (2004). Music of The Counterculture Era (1. publ. ed.). Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-313-32689-9.

- ↑ Norman, Philip (2009). John Lennon: The Life (1st Ecco pbk. ed.). New York: Ecco. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-06-075402-0.

- ↑ Reisch 2007, p. 144

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – A Nice Pair at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. Original A Nice Pair UK LP

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – A Nice Pair at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. 40th anniversary Europe two-CD

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. 40th anniversary Europe three-CD

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. 2011 remaster US CD

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – Discovery at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. Discovery Europe edition

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – The Discovery Box Set at Discogs". Discogs.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012. Discovery US edition

- 1 2 Povey 2007, pp. 4–5

- ↑ "The Concert Database Pink Floyd, 1971-06-20, A Perfect Union Deep In Space, Palaeur, Rome, Italy, Atom Heart Mother World Tour (c), roio". Pf-db.com. 28 March 2007. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ↑ Schaffner 2005, p. 156

- ↑ Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd – The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ↑ Schaffner 2005, p. 94

- ↑ Blake 2008, p. 102

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 189

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 185

- ↑ Chapman 2010, pp. 192–193

- ↑ "Syd Barrett Pink Floyd Psychedelic Music Progressive Music: Syd Barrett Stars - Everything (So Far)". Sydbarrettpinkfloyd.com. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (Media notes). Pink Floyd. EMI. 1967. SCX6157.

- ↑ Palacios 2010, pp. 206–207

- ↑ Chapman 2010, p. 170

- ↑ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Pink Floyd – Chart history" Billboard 200 for Pink Floyd. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Dutchcharts.nl – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Ultratop.be – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Czech Albums – Top 100". ČNS IFPI. Note: On the chart page, select 200737 on the field besides the word "Zobrazit", and then click over the word to retrieve the correct chart data. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ "Offiziellecharts.de – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Italian charts portal (06/09/2007)". italiancharts.com. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Norwegiancharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ↑ "Spanishcharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Swedishcharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Swisscharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Pink Floyd | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Lescharts.com – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". Hung Medien. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Italian album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "British album certifications – Pink Floyd – The Piper at the Gates of Dawn". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 12 August 2016. Enter The Piper at the Gates of Dawn in the field Keywords. Select Title in the field Search by. Select album in the field By Format. Select Gold in the field By Award. Click Search

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Piper at the Gates of Dawn |

- The Piper at the Gates of Dawn at Discogs (list of releases)