Oaks explosion

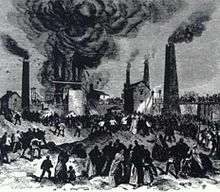

The Oaks explosion occurred at the Oaks Colliery,[lower-alpha 1] near Stairfoot, Barnsley, West Riding of Yorkshire, England (now within the new county of South Yorkshire), on 12 December 1866 killing 361 miners and rescuers. The disaster happened after a series of explosions caused by firedamp (chiefly methane) igniting ripped through the workings. It remains the worst colliery or mining disaster in England, and the second worst mining accident in the United Kingdom, after the Welsh Senghenydd Colliery Disaster.[1]

Background

The first shaft at the Oaks Colliery was sunk in the early 1830s. For nearly a decade no notable accidents happened, but in 1845 two separate explosions occurred. On both occasions few men were below ground so that "only three or four lives were sacrificed".[2] Two years later though there was an altogether more serious accident. It was "generally understood"[2] that firedamp had accumulated in old workings and was somehow ignited leading to an explosion. Of the men underground at the time seventy-three were killed and only twenty-six rescued.

As a result of this, the following year changes were made in the colliery. The downcast[lower-alpha 2] shaft was converted to an upcast shaft with a furnace burning continuously at its foot.[3] Two earlier shafts which only reached the topmost seam and had been abandoned earlier were brought into use as the downcast and "drawing" shaft. They were deepened to the lowest seams. Firedamp was collected in a gasometer from the upper workings and used to light the main roads underground.

The upcast pit was close to the Dearne and Dove Canal and was provided with coke ovens. Both were in the northern colliery site. The southern colliery site was the centre of activity with the two downcast pits. This latter was adjacent to the railway.[4]

The colliery covered about 450 acres (180 ha) of which two thirds had already been worked out.[5] The colliery was worked on the longwall principle, there being about 60 miles (97 km) of wall at the time of the 1866 explosion. The main or Barnsley seam is about 8 feet (2.4 m) thick. It is 280 yards (260 m) below the surface at the pit bottom, but dips significantly so that it reaches to 400 yards (370 m) at some places.[2] The Barnsley seam was known to be gassy. It was liable to sudden inrushes of firedamp, sometimes sufficient to put out the Geordie lamps used. On one occasion all the lamps for 1,500 yards (1,400 m) were put out. With all this gas and with the uneven levels of the seam there were pockets of gas building up, indeed it was recognised that the goaves[lower-alpha 3] were full of the firedamp.[6]

At the time of the explosion there were 131 colliers who actually cut the coal. Each collier had one or two "hurriers" to remove the coal. There were also horse-drivers and maintenance staff. Boys were employed to open the doors to allow wagons to pass, then close them to ensure the ventilation was maintained. In total 340 persons were in the mine.[5] The air circuit was over 3 miles (4.8 km) long. The induced draught was obtained from a pair of furnaces fed with fresh air around 70 yards (64 m) from the upcast shaft itself.[7]

In the inquiry which followed the explosion it transpired that the mine had not been inspected by government inspectors for "some years before the accident".[8]

Prelude

Prior to the explosion the colliery was known to be in a dangerous state, to the extent that some men refused to work it. Gas was making men giddy and faint.[lower-alpha 4] Men would not take a safety lamp near the goaves. According to Tomlinson the underviewers[lower-alpha 5] had chalked up messages "FIRE" in places.[6] Jeffcock reports this slightly differently: the fireman[lower-alpha 6] had written up the word "FIRE" but this was not unusual "more commented since that day than upon it".[9] At the beginning of December there had been a meeting between the men and the management to "complain about a weak point in the ventillation".[10] At the inquest after the explosion William Gibson gave evidence that the night before this meeting his master (Andrew Barker) had the "gas had fired at his lamp" and was "knocked up" after three and a half hours work. As a result of the conditions Gibson had left the colliery the Sunday before the explosion after four of five years employment.[10]

To improve the ventilation and deal with the gas issue it was resolved to drive a stone drift[lower-alpha 7] from near the pit bottom towards the more remote workings. Because this was passing through rock and not coal there was thought to be little risk of firedamp, and therefore it was being blasted though for "all speed".[11] It was hoped that the final stone would be blasted out that day linking the new drift to an existing passage.[12]

Explosion and rescue

On Wednesday 12 December 1866, with less than an hour of the shift remaining, a huge explosion ripped through the workings. Two dense columns of smoke and debris erupted from the downcast pits. At No. 1 pit the blast damaged the winding engine and broke the cage, disconnecting it from its rope. At No. 2 pit the cage was blown up into the headgear breaking a coupling. After about five minutes the ventilation resumed and fresh air was drawn back down the downcast pits.[13]

A new cage was attached to the rope in the No. 1 pit. Mr Dymond (the managing partner or proprietor of the colliery), Mr D Tewart (the underviewer) and Mr C Siddons (a deputy) descended first.[14] They found a number of badly burned men who were retrieved as soon as possible. After a new rope was put on Mr P Cooper, Mr John Brown, Mr Maddison, Mr Potter, Mr Kell, Mr Platts, Mr Minto (the under-viewer of Mount Osborne colliery) and various other engineers and deputies from surrounding collieries along with seventy or eighty men went down to make up the rescue party.[13] 20 live victims were sent up but 14 later died of their injuries. 50 bodies in "various conditions of ghastliness"[15] were recovered by the end of the first day. The few living men had managed to make their way to the shaft bottom where there was at least some air, those more distant succumbed to the effects of afterdamp, principally carbon monoxide. The dead were taken to their homes.[15] The injured were treated at the pit-head by local doctors who had gone to the scene.[10] The stable area at the foot of the pit had been destroyed and burnt; 18 animals had been killed.

The rescue parties had to work in relays. In one incident a party of 16 men were forced to the surface due to the foul air and yet were accused of cowardice by the bystanders. The few police present could not control the crowd, which invaded the pithead and interfered with operations. A telegram to the Chief Constable brought reinforcements and the area was cleared.[10]

The rescuers' progress was restricted due to roof falls and after-damp. Where it was possible to penetrate further into the mine bodies were found unburnt but damaged by the blast. Matthew Hague,[lower-alpha 8] a night deputy, told the inquest of finding 16 bodies between 100 yards (91 m) and 200 yards (180 m): "They were not burnt or scorched in the least, but appeared as if asleep."[10] James Marsh, a miner from "Worsbro'dale" (Worsbrough), tried to push on past Hague, but had to turn back "as the air was so bad"[10] During the day the rope and cage for the No. 1 shaft were repaired and brattice was sent down to repair the stoppings.[lower-alpha 9][10]

Around 22:00 Minto met up with Parkin Jeffcock, a mining engineer from Sheffield in the colliery office. Minto had previously been an under-viewer at the Oaks and could brief Jeffcock on the colliery and the steps taken so far. Jeffcock descended meeting Brown, Potter, Cooper and Platts coming off shift. At 01:30 most of the men below ground came up and Minto with Mr Smith (the mining engineer from Lundhill Colliery)went below. Minto met up with Tewart and following his directions went to the end of the stone drift where he met up with Jeffcock.[16]

Dymond and Brown who were supervising operations realised before the end of the first day that all the remaining men must be dead and from midnight underground operations were run down.[10]

Recovery attempts and further explosions

Jeffcock and Minto walked up the engine level checking stoppings. Part way up they encountered a strong blower of chokedamp (mainly carbon dioxide and nitrogen) which accounted for much of the foul air.[17]

Just after 05:00 Minto ascended to select and organise a hundred men to come down and start recovering the corpses. Jeffcock remained below trying to re-establish effective ventilation.[18] The rescuers went down the pit led by Smith, David Tewert (the underground steward), William Sugden (the deputy steward), Charles Siddon (the under deputy) and two firemen Thomas Madin and William Stevenson.

Hague was again underground at 08:30 the following morning working with Sugden. Both worked together in charge of a party of men about 650 yards (590 m) from the pit bottom. The mine "sucked", that is the air stream rapidly changed direction. This was a sure sign of an explosion and the men rushed to the pit bottom. All except Sugden were lifted out in six trips of the cage.[10] Fifteen men were on the cage, the normal number was six.[19] At the inquest Hague described it thus: "I found the air turned upon us, and we 'revolted' again. That is, we were sucked backwards and forwards in consequence of the explosion. I knew this, for I am one of the survivors of the explosion twenty years ago."[10] Minto descended to find out what was happening. He asked Tewart where Jeffcock and Smith were and after a brief search spent five minutes talking with Tewart Baker and Siddons. He regained the surface at 08:50.[20]

Jeffcock had earlier sent word that he thought the mine was heating up and advised that the shaft temperature be monitored. A party of men at the pithead had lowered a thermometer to check when the second explosion occurred at 08:55. The men were thrown backwards, the number 1 cage was thrown up into the headgear, dense clouds of smoke were emitted and large burning timbers hurled into the air. From the sound this appeared to those present to be a larger explosion that the first one.[10] A cage was lowered and shortly after raised but returned empty. It was now apparent that not only was everyone below ground dead, but also that little could be done to recover the bodies.[10]

At 19:40 a third explosion was observed and black smoke bellowed out of No. 2 pit which should have been a downcast pit. The ventilation had reversed and air was passing down the upcast shaft. A watch was kept from the surface.

Between 04:00 and 05:00 on Friday morning (14 December) the No. 1 pit signal bell was heard to ring. A bottle of brandy was lowered and, surprisingly, the bottle was removed. A small tub was attached to a rope and two men, T W Embleton and J E Mammatt were lowered down. The found and retrieved Samuel Brown who had been one of the recovery party from the previous morning. The two rescuers went a little distance into the mine but found no other living person and saw part of the colliery on fire.[21]

Abandonment and reopening

On Saturday 15 December three or four more explosions occurred.[21] Later that day a meeting between the colliery viewers and the government inspector concluded that nothing more could be done for those below, and with the mine alight the only option was to seal it to extinguish the fire. Accordingly on the following Monday (17 December) work started on sealing the three shafts.[10]

From the 30 January 1867 until 5 November that year hourly checks were made until it was deemed safe to reopen the pit.[10] Tomlinson describes a visit he made to the pithead during this time:

One shaft was filled up – chokeful of earth and rubbish ; the other had a wooden scaffold suspended by wire ropes, and let down about twenty yards. Upon this cage was first piled straw, &c., and then puddled clay ; so that, except a small aperture from a temporary iron pipe (which contains a valve to close or open the orifice at will), this shaft, also, was sealed up.

Tomlinson also described how the several hundred widows were surviving. Each widow received 10 shillings a week (5/- from the public relief fund and 5/- from the miners' union) equivalent to £49 in 2015[lower-alpha 10]. She was granted an additional two shillings and sixpence for each child under the age of thirteen. Should a widow remarry she would receive a bonus of £20 (equivalent to £1,965 in 2015), but all further benefit would cease.[22]

Once the shafts were reopened and ventilation established the task of recovering the bodies could commence. Jeffcock's body was discovered on Saturday 2 October 1869 and buried the following Monday.[23] The colliery finally reopened in December 1870. Around 150 bodies were known to still be underground and were being recovered. It was noted in contemporary reports that some of the bodies were still sufficiently preserved to permit identification.[24]

Cause

A thorough investigation into the disaster could not conclusively ascertain what had caused the explosion or what was the source of the first ignition. But some survivors mentioned an exceptionally violent blast just before the main explosion. This may have been caused by the driving of a drift near the main seam, meaning the digging of a new workings may have ignited pockets of firedamp. An initial blast may have caused a chain reaction triggering the firedamp and coal dust explosion that devastated the rest of the pit.

The findings of the inquest jury were mentioned in a House of Commons debate. They came to the conclusion that the deaths were due to an explosion of gas caused by a "great accumulation of gas" which they blamed upon management negligence.[8]

Although the cause was never properly discovered, a further 17 explosions would be recorded in the Oaks Colliery's history until it closed.

Legacy

A monument to all those killed in the disaster was erected at Christ Church, Ardsley, Barnsley, in 1879. A second monument was erected in 1913 to Parkin Jeffcock and the volunteer rescuers who were killed.[25][26]

The accident remained the worst in British mining history until the Senghenydd Colliery Disaster, in the South Wales coalfield in 1913, which claimed 439 lives. The Oaks disaster remains the worst in an English coalfield.

It was stated under oath and in two Command Reports to Parliament that the explosions killed 361 men and boys, based on 340 working below ground in the first explosion (with six survivors) and 27 rescuers being killed on 13 December. A 2016 volunteer research project by the Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership has produced a list of 383 individual names although not verified as died in the disaster.[27] The ages of those killed ranges from 10 to 67.

See also

Coordinates: 53°33′10.35″N 1°27′5.08″W / 53.5528750°N 1.4514111°Wgrid reference SE 36450 06366

Notes

- ↑ A colliery is a coal mine including both the underground workings and the surface equipment. A pit is a vertical shaft; by this date all mines had to have at least two shafts (see Hartley Colliery disaster for an explanation).

- ↑ Upcast and downcast refer to the direction in which air travels. Air is drawn down the downcast shaft, through the workings and exhausts through the upcast shaft. To force the air though modern mines use fans but at this date the best method was by induced draught from a furnace at the bottom of a shaft.

- ↑ Void from where the coal had been extracted

- ↑ Modern research suggests this would be due to oxygen deprivation rather than any methane poisoning. See Wikipedia's article on methane.

- ↑ Junior managers or foremen

- ↑ In this context a fireman is someone who tests for gas before each shift and if required will intentionally fire it in a controlled manner

- ↑ A drift is a roughly horizontal tunnel. A stone drift is a drift passing through rock other than coal.

- ↑ also spelled Haigh.

- ↑ Brattice is wood or canvas used to create partitions to direct the air flow. Stoppings are the permanent underground walls (wood, brick or stone) which force the air to follow the correct route throughout the mine and not just take the shortest path between pits.

- ↑ UK Consumer Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth.com.

References

- ↑ BBC 2011.

- 1 2 3 Tomlinson 1868, p. 226.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1868, p. 227.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey 1855.

- 1 2 Jeffcock 1867, p. 111.

- 1 2 Tomlinson 1868, p. 228.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, p. 112.

- 1 2 Hansard 1868, col 942.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Taylor 2016.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1868, p. 229.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, p. 114.

- 1 2 Jeffcock 1867, p. 116.

- ↑ Embleton 1876, p. 30.

- 1 2 Tomlinson 1868, p. 224.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, pp. 118–120.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, p. 120.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, p. 122.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, p. 123.

- ↑ Jeffcock 1867, p. 124.

- 1 2 Tomlinson 1868, p. 225.

- ↑ Tomlinson 1868, p. 234.

- ↑ Clipping from "The Standard" of October 9 1869 pasted onto the last page of Jeffcock 1867

- ↑ The Graphic 1870, p. 583.

- ↑ Ball 2005.

- ↑ Woodtyke 2010.

- ↑ Barnsley MBC 2016.

Bibliography

- Ball, Dave (18 July 2005), Oaks Colliery Disaster Rescuers' Memorial, Sheffield Hallam University, retrieved 9 December 2016

- Barnsley MBC (2016), Oaks Disaster Victims, Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership, retrieved 9 December 2016

- BBC (18 September 2011), "Major mining disasters in Britain", BBC News (UK), BBC, retrieved 9 December 2016

- Duckham, Helen; Duckham, Baron (1973), Great Pit Disasters: Great Britain 1700 to the present day, Newton Abbot: David & Charles, ISBN 0715357174

- Embleton, T W (1876), "Notes on the Oaks Colliery explosion, ot the 12th December, 1866, and on the subsequent explosions", North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers: Transactions, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, XXV: 29–40, retrieved 11 December 2016

- The Graphic (17 December 1870), Home News, Illustrated Newspapers, retrieved 11 December 2016

- Hansard (26 May 1868). "Motion for a commission". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). United Kingdom: House of Commons. col. 939–945. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Jeffcock, John Thomas (1867), Parkin Jeffcock, civil and mining engineer. A memoir by his brother, London: Bemrose and Lothian, retrieved 11 December 2016

- Ordnance Survey (1855), Yorkshire 274 (includes: Barnsley; Darton; Dodworth.), Six-inch England and Wales, 1842-1952, Ordnance Survey, retrieved 12 December 2016

- Taylor, Fionn, ed. (8 November 2016), The Oaks. Barnsley, Yorkshire 13th December 1866, retrieved 9 December 2016

- Tomlinson, John (1868), "The Oaks Colliery two months after an explosion", Stories and sketches relating to Yorkshire, London: Simpkin, Marshall, & co, pp. 223–236, retrieved 9 December 2016

- Woodtyke (22 November 2010), Oaks Colliery Disaster Rescuers' Memorial Barnsley Yorkshire 2, Flickr, retrieved 9 December 2016