Lost Library of the Moscow Tsars

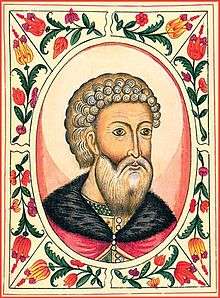

The Lost Library of the Moscow Tsars also known as the "Golden Library," is a library speculated to have been created by Ivan III (the Great) of Russia in the sixteenth century.[1] It is also known as the Library of Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible) to whom it is believed the disappearance of the library is attributed. The lost library is thought to contain rare Greek, Latin, and Egyptian works from the Libraries of Constantinople and Alexandria, as well as second century Chinese texts and manuscripts from Ivan IV's own era. The library has been historically placed as being underneath the Kremlin and has been a source of interest for researchers, archaeologists, treasure hunters, and historical figures like Peter the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte. Under Ivan IV's rule the library's legend had grown. Myths surrounding the library include: Ivan cursing the library before his death causing blindness to those that came close to locating the library and Ivan attempting to have scholars translate the ancient texts in order to gain knowledge of black magic.[1]

History

The earliest reference to the lost library was in 1518 when Michail Tripolis known widely as Maximus the Greek was sent to Russia and came into contact with Moscow Grand Prince Vasili III, the son of Ivan III. Tripolis' reputation as a scholar and translator of works like the Psalter into Russian brought him to the attention of Vasili III.[2] It was in a meeting between Michail and Vasili wherein it is described that "countless multitudes of Greek books" were shown to Michail by Vasili III. A Russian contemporary of Michail wrote a biography of him called "The Tale of Maxim the Philosopher." This biographer, Prince Kurbskii, a member of the Moscow nobility, detailed this meeting meeting between Michail and Vasili III. Kurbskii wrote that "Maxim was astounded and impressed, and assured the prince that even in Greece he had never seen so many Greek books."[3]:304

Close to eighty years after Kurbskii wrote Maximus the Greek's biography the next mention of the lost library as well as a location appeared. Livonian writer Franz Nyenstadt wrote about Johannes Wetterman, a German Protestant minister who established a church in Russia and met with Ivan IV. Ivan IV purportedly had been hiding multitudes of weapons underneath the Kremlin. Some of the weapons were actually discovered in 1978 by Soviet construction workers working on the subway.[4] Wetterman was summoned by Ivan IV not to look at a weapons arsenal but to look at ancient books that had been secured in a locked storeroom somewhere inside the Kremlin for well over a hundred years. Wetterman and three other Germans and three Russian officials were told to conduct a survey of the works. Wetterman noted that there were many works present that were only referenced in passing by other scholars because they had been either destroyed in fires or lost during wars previously. Wetterman was offered the opportunity to work with and translate a book found in the survey. Wetterman however was afraid that taking such an assignment would lead to more work which would keep him in Moscow indefinitely. The works were then locked away again in the underground Kremlin perhaps to protect them from potential fires.

A 1724 report of Moscow Petty Official Konon Osipov mentions a discovery made by V. Makariev in 1682. Makariev while being ordered to go into a Kremlin secret passage found a room full of trunks. When Makariev reported the find to Princess Sophia Alekseyevna she made it forbidden for anyone to access those rooms.[3]:306–307,310

Search for the Lost Library

In the early nineteenth century, Professor Dabelov of the University of Dorpat (University of Tartu) found in the archives of the city of Pernau (Parnu), a document called "Manuscripts Held by the Tsar." Dabelov left Pernau to inform a university associate, Professor Clossius, of the find, yet when returning to the Pernau archives the document had seemingly vanished. The only information left on the document was some of what Dabelov had copied down on his first visit. This information detailed that the tsars had around 800 manuscripts and some of these were gifted to Russia from an unknown Byzantine emperor.

In 1834, Professor Clossius wrote on a collection of Russian history including the work of Nikolay Karamzin author of "History of the Russian State." Karamzin mentions the meeting between Ivan IV and Protestant minister Wetterman. In Professor Clossius' article, he wrote that he believed the lost library had been destroyed by fires caused by the seventeenth century Polish invasion.

In the 1890s, Professor Thraemer of the University of Strasbourg located a manuscript of Homer's hymns that he believed was once a part of the collection of manuscripts brought to Moscow by Byzantine Princess Sophia Palaiologina when she married Ivan III. Ivan III and Sophia married in 1472 and her dowry included a rare collection of books from the Library of Constantinople and Library of Alexandria.[1] For several months in 1891 Professor Thraemer lived in Moscow searching through all of the city's libraries and archives in the hopes of locating the lost library. Thraemer eventually decided that it must be located inside hidden subterranean rooms underneath the Kremlin. In 1893 Professor I.E. Zabelin wrote an article called "The Underground Chambers of the Moscow Kremlin" where he concluded that the library did exist there but that it was destroyed in the seventeenth century. Around this time some attempts were made at excavating underneath the Kremlin. The excavations found several underground chambers and tunnels but all were found empty. Several Russian scholars of the era also refuted the existence of the library. S.A. Belokurov in 1898 wrote that the "Tale of Maxim the Philosopher" was not written by Prince Kurbskii, but 75 years after the fact by another monk. Belokurov states that he found enough contradictions and inconsistencies in the Maximus the Greek biography that he believed Maximus never even saw the library. Belokurov also believed that Professor Dabelov's document was a forgery and he refuted other sources as well.[3]:310–311

In the early twentieth century Archaeologist Ignatius Stelletskii became a seeker of the lost library. A 1929 article of The New York Times details Stelletskii's search. The article reports that Stelletskii found archives showing "two large rooms filled with treasure chests and known to exist under the Kremlin" half a century after the death of Ivan IV. Also reported is the fact that Protestant Minister Wetterman never returned home after being in Moscow. Ivan IV according to myth had the architect of Saint Basil's Cathedral blinded in order to never be able to recreate it, hiding its secrets. Therefore, Ivan IV involved in Wetterman's disappearance after seeing the library would seem standard protocol. Peter the Great also attempted to locate the library hoping to find treasures that would help the treasury after his several years involved in wars.[5] Stelletskii's search however ended without ever finding the library.

S.O. Shmidt in 1978 described an unpublished work by N.N. Zarubin from the 1930s called "The Library of Ivan the Terrible and His Books." Zarubin argued that the work of S. Belokurov was not impartial when claiming that the library did not exist.[3]:312–313

By the 1990s archaeologists broadened their search beyond the Kremlin into Sergiyev Posad, Alexandrov, Vladimir Oblast, and Dyakovo, all places under the influence of Ivan IV.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 "The Search for the Lost Library of Ivan the Terrible". Ancient Origins. Ancient Origins. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Golubinskii, E.E. (1900). Istoriia Russkoi Tserkvi (Volume 2, Part 1). Moscow, Russia: Universitetskaia Tipografiia.

- 1 2 3 4 Arans, David (1983). "A Note on the Lost Library of the Moscow Tsars". Journal of Library History. 18 (3): 304–316. JSTOR 25541406.

- ↑ Hamilton, Masha (June 28, 1989). "Kremlin Tunnels: The Secret of Moscow's Underworld". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Duranty, Walter (March 6, 1929). "Ivan's Tresures Lure Russia Again". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 November 2016.