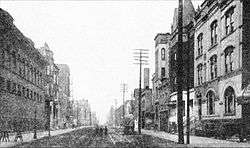

The Levee, Chicago

The Levee District was the red-light district of Chicago, Illinois, from the 1880s until 1912, when police raids shut it down. The district, like many frontier town red-light districts, got its name from its proximity to wharves in the city. The Levee district encompassed 4 blocks in Chicago’s South Loop area, between 18th and 22nd street.[1] It was home to many brothels, saloons, dance halls, and the famed Everleigh Club. Prostitution boomed in the Levee District, and it was not until the Chicago Vice Commission submitted a report on the city’s vice districts that it was shut down.

History

The Levee District opened in the 1880s and was home to many brothels, saloons, dance halls, and similar places. These businesses ranged from rough dives, like Pony Moore’s or the Turf Exchange Saloon, to prestigious, infamous clubs like The Everleigh Club.

In order to receive protection, Levee inhabitants would annually attend the biggest event in the district, The First Ward Ball. The First Ward Ball was an event in which Levee residents gathered to celebrate the triumphs brought to them by Michael 'Hinky Dink' Kenna and “Bathouse” John Coughlin. Madams, corrupt businessmen, dance-hall owners, saloon owners, prostitutes, brothel owners, and gamblers attended the event to support their aldermen for continuing to protect them from the law. The money they raised came from the purchase of tickets for the event and alcohol. When anti-vice reformers protested the ball, Kenna justified it as benefiting the people in the district through education and community programs. The First Ward Ball of 1908 was the most significant ball because it was the last that the most prominent figures of the Levee attended. That year, anti-vice reformers had tried to stop the ball by bombing The Coliseum, the arena where it would be held. The ball still went on and was successful. The following ball would prove otherwise. The First Ward Ball of 1909 was unsuccessful because anti-vice reformers worked towards getting the city to revoke the event's alcohol license. They succeeded, and about 3,000 people attended, less than a quarter of the attendance of the previous balls. That year, reformers like the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), worked towards stopping events like these because they felt that they harmed the families in the Levee.[2]

Anti-Vice Reformers

The Levee district's success in vice came to an end when reformers such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and Chicago Vice Commission CVC (established by Carter Harrison, Jr.) worked towards publicly exposing the issues of white slavery and alcohol. The WCTU had a “department of rescue” to save women forced into slavery. They also had a “department of social purity,” which raised sexual consent laws. The WCTU paid investigators to conduct studies on forced prostitution in Midwest lumber camps that would help them publish a journal of stories of women working as prostitutes in Chicago (Levee District), San Francisco, and New York.[3]

The Chicago Vice Commission, focused terminating vice districts, also worked towards investigating the conditions for women in the Levee.The members spoke to prostitutes, police, and neighborhood organizations to investigate the issue of prostitution. They published a report, The Social Evil in Chicago, which included prostitution statistics and recommendations for improvement. The report concluded that about 5,000 professional prostitutes worked in Chicago, and about 5 million men were receiving services from them, for which the women received about $25 weekly. They were mostly uneducated and unskilled, and they had little to no opportunities for economic advancement. The report was read around the world and influenced vice commissions in 43 cities to close vice districts.[4]

Closure of The Levee

It was long, hard process to close down the entire Levee District. It began on January 9th, 1910, when Nathaniel Ford Moore died in Vic Shaw’s brothel. She wanted to frame Minna Everleigh for the death, but Everleigh found out about Moore before Shaw got the chance. Thus, Shaw was forced to call the police to report the death after which her brothel was closed. A year later, on October 3rd, 1911, the state’s attorney issued warrants for 135 people associated with the Levee, including Big Jim Colosimo, Ed Weiss, Roy Jones and Vic Shaw. The warrants shut down halls, saloons and brothels. Many people were arrested within the brothels; in Marie Blanchey’s brothel, 20 women and 30 men were arrested. Word spread about corruption in the government so, on October 24th, 1911, Mayor Harrison ordered the closure of the Everleigh Club which was shut down the next day. Many businesses in the Levee District closed in 1911, but the district held on for two more years. One of the last brothels to close was Freiberg’s Dance Hall, which celebrated its last night on August 24th, 1914.[5]

Notable persons associated with the Levee District

- Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna was the alderman of the First Ward who owned a saloon on Clark street called the Workingman’s Exchange. Here he would bribe people to vote for him by offering a free lunch and mug of beer for a nickel.

- “Bathhouse” John Coughlin ran the First Ward with Hinky Dink and owned a tavern on West Madison named, “Silver Dollar Saloon.” Many people called him “Bathhouse” John.

- Ada Everleigh was the owner and madam of the Everleigh Club with her younger sister Minna. Ada played the role as the executive who balanced the books. She also made it her priority to keep the club clean and spent half of her time wiping the mirrors, straightening oil paintings, and checking the Gold Piano for marks (the Gold Room was her favorite room). The Everleigh Club was the best brothel in the Levee and girls considered it to be a superior position to get picked into staying there.

- Minna Everleigh was the owner and madam of the Everleigh Club with her sister Ada Everleigh. She was the mingler, the one who did all the talking for the club. She was almost framed for the murder of two different men, Marshall Field Jr. first and Nathaniel Ford Moore five years later by Vic Shaw, who also convinced Pony Moore (who had no relation to Nathaniel) to go in on it the first time by bribing him $40,000.

- Ike Bloom, his real name was Isaac Gitelson and he made arrangements for protection payments with the police for the Levee District. He also operated a dance hall, the Freidberg, which he said was a dance academy to keep reformers from finding out the truth. This dance hall had a bar in the front with a long dance room in the back and an orchestra on the balcony. His rules for the girls in his hall were: she must report in by nine p.m. every night, persuade men to spend at least 40 cents every time they bought a round, and to lure guys to the Marlborough Hotel.

- Jim Colosimo, aka "Big Jim," ran a white slavery ring where he had girls depend on him for praise and protection. Girls would be lured to Chicago by promising those good jobs and nice homes, only to be sold to other brothel owners. He loved diamonds and was always playing with them in his hands; he would buy them from thieves or win them by gambling. In 1920 he was shot in his café and died.

- Victoria Colosimo was married to Jim Colosimo and helped him run pool halls and saloons. She operated two of the dives, the Victoria and the Saratoga.

- Maurice Van Bever, Big Jim’s partner; operated two saloons called the Paris and the White City.

- Ed Weiss, brothel owner next to the Everleigh Club who would pay off the Levee cabdrivers to drive drunken men to his door instead of the Everleigh Club.

- Vic Shaw, born Emma Elizabeth Fitzgerald. A madam to a house on South Dearborn Street who hated and felt threatened by the Everleigh sisters. Her girls were not treated very well. They were harshly disciplined and not always given proper examinations by doctors.

- Pony Moore was the owner of two levee dives called the Turf Exchange Saloon and the Hotel De Moore resort.

- John “Mushmouth” Johnson was the first African American vice lord who opened a saloon and gambling house on State Street.

- Reverend Ernest Albert Bell, a preacher who would walk around the Levee streets every night besides Monday to protest the Custom House Place and tried to get the mayor to close it.

- George Little owned a saloon called Here It Is and ran a combination bar and brothel called the Imperial on Armour Avenue, right next to one of Van Bever’s dives. He was also considered to the Levee Czar meaning he was sent personally by Hinky Dink and Big Jim to collect protection payments.

- Roy Jones, Vic Shaw’s husband who operated a casino on State Street.

- Belle Schrieber, a working girl in the Everleigh Club, who was kicked out for sneaking around with a boxer named Jack Johnson.

- Lillian St. Clair, also kicked out of the Everleigh Club for the Jack Johnson incident.

- Bessie Wallace, also kicked out of the Everleigh Club for the Jack Johnson incident.

- Virginia Bond, also kicked out of the Everleigh Club for the Jack Johnson incident.

- Monsieur Emond, a French dressmaker at the Everleigh Club, who had told a man investigating Marshall Field Jr's death the name of two girls in the Club, going by the names of Camille and Hughs, who had played a role in his murder.

- Panzy Williams, Madam of a brothel, who was convicted for refusing to surrender one of her girls to her parents, who had asked for their daughter back in 1907.

Prostitution in Chicago After the Levee District

Although the Levee District had closed down in 1912, prostitution continued to be a problem in Chicago. The closing of the Levee had initiated changes throughout the city's sexual commerce. There were no longer brothels, but that didn’t stop many men and women. They moved from brothels and saloons to cabarets, nightclubs and other nighttime scenes. Solicitation was still available, and the sex entrepreneurs were still willing to pay law enforcement to keep quiet. In the beginning of the 1920s, vice syndicates of the time moved to the suburbs where law enforcement was easier to persuade.[6] Although laws were established to control or eliminate prostitution, they were not backed up by the court system. "In many cases, the defendant did not appear in trial in which case the charges were dropped and the bond seized."[7] It was shown that even when they were sentenced, none of the prostitutes were sentenced correctly. Only 15 of the 320 cases were found guilty in a group of cases they had selected.[7] In the last decades of the 20th century, establishments similar to brothels reentered the city. New businesses like peepshows, massage parlors, and bars featuring live showgirls opened. In the 1980s, however, most were shut down and turned into condominiums, restaurants, and high-end retail stores.[8]

References

- ↑ ”Vice Districts.” Vice Districts. N.p., n.d. Web. 5 Dec. 2013. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1304.html..

- ↑ Kendall. “First Ward Ball.” Chicagocrimescenes.blogspot.Blogspot, 9 May. 2009. Web. 27 Nov. 2013,

- ↑ Kubal, Timothy. “White Slave Crusades: Race Gender and Anti-Vice Activism 1887-1917 (review).” Journal of Social History, Volume 40, Number 4, (2007): 1057-1059. Web. 27 Nov 2013.

- ↑ Linehan, Mary. “Vice Commissions.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago: The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago, 2005. Web. 27 Nov. 2013

- ↑

- Abbott, Karen (2007) Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys, and the Battle for America's Soul. New York: Random House ISBN 978-1-4000-6530-1

- Asbury, Herbert (1940). Gem of the Prairie. New York: Knopf.

- ↑ Cynthia Blair Prostitution Electronic Historical Encyclopedia of Chicago 2005

- 1 2 Courts fail to back city's tough prostitution law: study: Courts fail to back city prostitution law Swanson, Stevenson Chicago Tribune (1963-Current file); Nov 19, 1981; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Chicago Tribune (1849-1990) p. N1

- ↑ Cynthia Blair Prostitution Electronic Historical Encyclopedia of Chicago 2005

External links

Media related to The Levee (Chicago) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Levee (Chicago) at Wikimedia Commons

Coordinates: 41°51′22″N 87°37′44″W / 41.856°N 87.629°W