The KLF

| The KLF | |

|---|---|

| Also known as |

|

| Origin | London, England |

| Genres | |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Associated acts | |

| Past members | |

The KLF (also known as The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu, furthermore known as The JAMs and The Timelords and by other names) are a British electronic band of the late 1980s and early 1990s.[4]

Beginning in 1987, Bill Drummond (alias King Boy D) and Jimmy Cauty (alias Rockman Rock) released hip hop-inspired and sample-heavy records as The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu, and on one occasion (the British number one hit single "Doctorin' the Tardis") as The Timelords. The KLF released a series of international hits on their own KLF Communications record label, and became the biggest-selling singles act in the world for 1991.[5] The duo also published a book, The Manual (How to Have a Number One the Easy Way), and worked on a road movie called The White Room.

From the outset, they adopted the philosophy espoused by esoteric novel series The Illuminatus! Trilogy, gaining notoriety for various anarchic situationist manifestations, including the defacement of billboard adverts, the posting of prominent cryptic advertisements in NME magazine and the mainstream press, and highly distinctive and unusual performances on Top of the Pops. Their most notorious performance was a collaboration with Extreme Noise Terror (and Barney Greenaway of Napalm Death) at the February 1992 BRIT Awards, where they fired machine gun blanks into the audience and dumped a dead sheep at the aftershow party. This performance announced The KLF's departure from the music business, and in May 1992 the duo deleted their entire back catalogue.

With The KLF's profits, Drummond and Cauty established the K Foundation and sought to subvert the art world, staging an alternative art award for the worst artist of the year and burning one million pounds sterling. Drummond and Cauty remained true to their word of May 1992; the KLF Communications catalogue remains deleted in the UK, but The White Room is still being pressed in the U.S. by Arista. They have released a small number of new tracks since then, as the K Foundation, The One World Orchestra and most recently, in 1997, as 2K.

History

In 1986, Bill Drummond was an established figure within the British music industry, having co-founded Zoo Records,[6] played guitar in the Liverpool band Big in Japan,[7] and worked as manager of Echo & the Bunnymen and The Teardrop Explodes.[8] On 21 July of that year, he resigned from his position as an A&R man at record label WEA, citing that he was nearly 33⅓ years old (33⅓ revolutions per minute being significant to Drummond as the speed at which a vinyl LP revolves), and that it was "time for a revolution in my life. There is a mountain to climb the hard way, and I want to see the world from the top".[9] He released a well-received solo LP, The Man, judged by reviewers as "tastefully understated,"[10] a "touching if idiosyncratic biographical statement"[11] encapsulating "his bizarrely sage ruminations",[12] and "a work of humble genius: the best kind".[11]

Artist and musician Jimmy Cauty was, in 1986, the guitarist in the commercially unsuccessful three-piece Brilliant[10]—an act that Drummond had signed to WEA Records and managed.[13] Cauty and Drummond shared an interest in the esoteric conspiracy novels The Illuminatus! Trilogy and, in particular, their theme of Discordianism, a form of post-modern anarchism. As an art student in Liverpool, Drummond had been involved with the set design for the first stage production of The Illuminatus! Trilogy, a 12-hour performance which opened in Liverpool on 23 November 1976.[14][15]

Re-reading Illuminatus! in late 1986, and influenced by hip-hop, Drummond felt inspired to react against what he perceived to be the stagnant soundscape of popular music. Recalling that moment in a later radio interview, Drummond said that the plan came to him in an instant: he would form a hip-hop band with former colleague Jimmy Cauty, and they would be called The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu.

It was New Year's Day ... 1987. I was at home with my parents, I was going for a walk in the morning, it was, like, bright blue sky, and I thought "I'm going to make a hip-hop record. Who can I make a hip-hop record with?". I wasn't brave enough to go and do it myself, 'cause, although I can play the guitar, and I can knock out a few things on the piano, I knew nothing, personally, about the technology. And, I thought, I knew [Jimmy], I knew he was a like spirit, we share similar tastes and backgrounds in music and things. So I phoned him up that day and said "Let's form a band called The Justified Ancients of Mu-Mu". And he knew exactly, to coin a phrase, "where I was coming from". And within a week we had recorded our first single which was called "All You Need Is Love".— [16]

The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu

Early in 1987, Drummond and Cauty's collaborations began. They assumed alter egos – King Boy D and Rockman Rock respectively – and adopted the name The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (The JAMs), after the fictional conspiratorial group "The Justified Ancients of Mummu" from The Illuminatus! Trilogy. In those novels, the JAMs are what the Illuminati (a political organisation which seeks to impose order and control upon society) call a group of Discordians who have infiltrated the Illuminati in order to feed them false information. As The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu, Drummond and Cauty chose to interpret the principles of the fictional JAMs in the context of music production in the corporate music world. Shrouded in the mystique provided by their disguised identities and the cultish Illuminatus!, they mirrored the Discordians' gleeful political tactics of causing chaos and confusion by bringing a direct, humorous but nevertheless revolutionary approach to making records, often attracting attention in unconventional ways. The JAMs' primary instrument was the digital sampler with which they would plagiarise the history of popular music, cutting chunks from existing works and pasting them into new contexts, underpinned by rudimentary beatbox rhythms and overlaid with Drummond's raps, of social commentary, esoteric metaphors and mockery. (This technique is rather similar to that used by The Residents on their album Meet the Residents).

The JAMs' debut studio single "All You Need Is Love" dealt with the media coverage given to AIDS, sampling heavily from The Beatles' "All You Need Is Love" and Samantha Fox's "Touch Me (I Want Your Body)". Although it was declined by distributors fearful of prosecution, and threatened with lawsuits, copies of the one-sided white label 12" were sent to the music press; it received positive reviews and was made "single of the week" in Sounds.[17] A later piece in the same magazine called The JAMs "the hottest, most exhilarating band this year .... It's hard to understand what it feels like to come across something you believe to be totally new; I have never been so wholeheartedly convinced that a band are so good and exciting."[18]

The JAMs re-edited and re-released "All You Need Is Love" in May 1987, removing or doctoring the most antagonistic samples; lyrics from the song appeared as promotional graffiti, defacing selected billboards. The re-release rewarded The JAMs not just with further praise (including NME´s "single of the week")[19] but also with the funds necessary to record their debut album. The album, 1987 (What the Fuck Is Going On?), was released in June 1987. Included was a song called "The Queen and I", which sampled large portions of the ABBA single "Dancing Queen".[20] The recording came to the attention of ABBA's management and, after a legal showdown with ABBA[21] and the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society,[22] the 1987 album was forcibly withdrawn from sale. Drummond and Cauty travelled to Sweden in hope of meeting ABBA and coming to some agreement, taking an NME journalist and photographer with them, along with most of the remaining copies of the LP.[23] They failed to meet ABBA, so disposed of the copies by burning most of them in a field and throwing the rest overboard on the North Sea ferry trip home. In a December 1987 interview, Cauty maintained that they "felt that what [they]'d done was artistically justified."[24]

Two new singles followed 1987, on The JAMs' "KLF Communications" independent record label. Both reflected a shift towards house rhythms. According to NME, The JAMs' choice of samples for the first of these, "Whitney Joins The JAMs" saw them leaving behind their strategy of "collision course" to "move straight onto the art of super selective theft".[25] The song uses samples of the Mission: Impossible and Shaft themes alongside Whitney Houston's "I Wanna Dance With Somebody". Ironically, Drummond has claimed that The KLF were later offered the job of producing or remixing a new Whitney Houston album as an inducement from her record label boss (Clive Davis of Arista Records) to sign with them.[26][27][28] Drummond turned the job down, but nonetheless The KLF signed with Arista as their American distributors. The second single in this sequence – Drummond and Cauty's third and final single of 1987 – was "Down Town", a dance record built around a gospel choir and "Downtown" by 1960s star Petula Clark.[29] These early works were later collected on the compilation album Shag Times.

A second album, Who Killed The JAMs?, was released in early 1988. Who Killed The JAMs? was a rather less haphazard affair than 1987, earning the duo at least one five-star review (from Sounds Magazine, who called it "a masterpiece of pathos".[30])

The Timelords

In 1988, Drummond and Cauty became "Time Boy" and "Lord Rock", and released a 'novelty' pop single, "Doctorin' the Tardis" as The Timelords. The song is predominantly a mash-up of the Doctor Who theme music, "Block Buster!" by Sweet and Gary Glitter's "Rock and Roll (Part Two)".

Also credited on the record was "Ford Timelord", Cauty's 1968 Ford Galaxie American police car (claimed to have been used in the film Superman IV filmed in the UK). Drummond and Cauty declared that the car had spoken to them, giving its name as Ford Timelord, and advising the duo to become "The Timelords".[31]

Drummond and Cauty later portrayed the song as the result of a deliberate effort to write a number one hit single. In interviews with Snub TV and BBC Radio 1,[32] Drummond said that the truth was that they had intended to make a house record using the Doctor Who theme. After Cauty had laid down a basic track, Drummond observed that their house idea wasn't working and what they actually had was a Glitter beat. Sensing the opportunity to make a commercial pop record they abandoned all notions of underground credibility and went instead for the lowest common denominator. According to the British music press, the result was "rancid",[33] "pure, unadulterated agony" and "excruciating"[34] and – in something of a backhanded compliment from the normally supportive Sounds Magazine – "a record so noxious that a top ten place can be its only destiny".[33] They were right: the record went on to sell over one million copies.[35] A single of The Timelords' remixes of the song was released: "Gary Joins The JAMs" featured original vocal contributions from Glitter himself, who also appeared on Top of the Pops to promote the song with The Timelords.

The Timelords released one other product, a 1989 book called The Manual (How to Have a Number One the Easy Way), a step-by-step guide to achieving a number one hit single with little money or talent.

The KLF

By the time the JAMs' single "Whitney Joins The JAMs" was released in September 1987, their record label had been renamed "KLF Communications" (from the earlier "The Sound of Mu(sic)"). However, the duo's first release as The KLF was not until March 1988, with the single "Burn the Bastards"/"Burn the Beat" (KLF 002). Although the Justified Ancients of Mu Mu name was not yet retired, most future Drummond and Cauty releases would go under the name "The KLF".

The name change accompanied a change in Drummond and Cauty's musical direction. Said Drummond (as 'King Boy D') in January 1988, "We might put out a couple of 12" records under the name The K.L.F., these will be rap free just pure dance music, so don't expect to see them reviewed in the music papers". King Boy D also claimed that he and Rockman Rock were "pissed off at [them]selves" for letting "people expect us to lead some sort of crusade for sampling".[36] In 1990 he recalled that "We wanted to make [as The KLF] something that was ... pure dance music, without any reference points, without any nod to the history of rock and roll. It was the type of music that by early '87 was really exciting me ... [although] we weren't able to get our first KLF records out until late '88".[32]

The 12" records subsequently released in 1988 and 1989 by The KLF were indeed rap free and house-oriented; remixes of some of The JAMs tracks, and new singles, the largely instrumental acid house anthems "What Time Is Love?" and "3 a.m. Eternal", the first incarnations of later international chart successes. The KLF described these new tracks as "Pure Trance". In 1989, The KLF appeared at the Helter Skelter rave in Oxfordshire. "They wooed the crowd", wrote Scotland on Sunday some years later, "by pelting them with ... £1,000 worth of Scottish pound notes, each of which bore the message 'Children we love you'".[37]

Also in 1989, The KLF embarked upon the creation of a road movie and soundtrack album, both titled The White Room, funded by the profits of "Doctorin' The Tardis".[38] Neither the film nor its soundtrack were formally released, although bootleg copies of both exist. The soundtrack album contained pop-house versions of some of the "pure trance" singles, as well as new songs, most of which would appear (albeit in radically reworked form) on the version of the album which was eventually released to mainstream success. A single from the original album was released, however: "Kylie Said to Jason", an electropop record featuring references to Todd Terry, Rolf Harris, Skippy the Bush Kangaroo and BBC comedy programme The Good Life. In reference to that song, Drummond and Cauty noted that they had worn "Pet Shop Boys infatuations brazenly on [their] sleeves".[39]

The film project was fraught with difficulties and setbacks, including dwindling funds. "Kylie Said to Jason", which Drummond and Cauty were hoping could "rescue them from the jaws of bankruptcy", flopped commercially, failing even to make the UK top 100. In consequence, The White Room film project was put on hold, and The KLF abandoned the musical direction of the soundtrack and single.[40] Meanwhile, "What Time Is Love?" was generating acclaim within the underground clubs of continental Europe; according to KLF Communications, "The KLF were being feted by all the 'right' DJs".[40] This prompted Drummond and Cauty to pursue the acid house tone of their Pure Trance series. A further Pure Trance release, "Last Train to Trancentral", followed. At this time, Cauty had co-founded The Orb as an ambient side-project with Alex Paterson.[41] Cauty and Paterson DJ-ed at the monthly "Land Of Oz" house night in London, and The KLF's seminal 1990 "ambient house" LP Chill Out was born partly from these sessions. The ambient album Space and The KLF's ambient video Waiting were also released in 1990, as was a heavier, more industrial sounding dance track, "It's Grim Up North", under The JAMs' moniker.

In 1990 The KLF launched a series of singles with an upbeat pop-house sound which they dubbed "Stadium House". Songs from The White Room soundtrack were re-recorded with rap and more vocals (by guests labelled "Additional Communicators"), a sample-heavy pop-rock production and crowd noise samples. The results brought The KLF international recognition and acclaim. The first "Stadium House" single, "What Time Is Love?", released in August 1990, reached number five in the UK Singles Chart and hit the top-ten internationally. The follow-up, "3 a.m. Eternal", was an international top-five hit in January 1991, reaching number one in the UK and number five in the US Billboard Hot 100. The album The White Room followed in March 1991, reaching number three in the UK. A substantial reworking of the aborted soundtrack, the album featured a segued series of "Stadium House" songs followed by downtempo tracks.

The KLF's chart success continued with the single "Last Train to Trancentral" hitting number two in the UK, and number three in the Eurochart Hot 100.[42] In December 1991, a re-working of a song from 1987, "Justified & Ancient" was released, featuring the vocals of American country star Tammy Wynette. It was another international hit—peaking at number two in the UK, and number 11 on the Billboard Hot 100—as was "America: What Time Is Love?", featuring the vocals of ex-Deep Purple member Glenn Hughes (number four on the UK singles chart), a hard, guitar-laden reworking of "What Time Is Love?".

In 1990 and 1991, The KLF also remixed tracks by Depeche Mode ("Policy of Truth"), The Moody Boys ("What Is Dub?"), and Pet Shop Boys ("So Hard" from the Behaviour album, and "It Must Be Obvious"). Pet Shop Boy Neil Tennant described the process: "When they did the remix of 'So Hard', they didn't do a remix at all, they re-wrote the record ... I had to go and sing the vocals again, they did it in a different way. I was impressed that Bill Drummond had written all the chords out and played it on an acoustic guitar, very thorough."[43]

After successive name changes and a plethora of highly influential dance records, Drummond and Cauty ultimately became, as The KLF, the biggest-selling singles act in the world for 1991,[5][44] still incorporating the work of other artists but in less gratuitous ways and predominantly without legal problems.

Vocalists Wanda Dee and Ricardo da Force featured on many of The KLF's hits. In addition to her own show, Dee still performs as "Wanda Dee of the KLF".

Retirement

On 12 February 1992, The KLF and crust punk group Extreme Noise Terror performed a live version of "3 a.m. Eternal" at the BRIT Awards, the British Phonographic Industry's annual awards show; a "violently antagonistic performance" in front of "a stunned music-business audience".[45] Drummond and Cauty had planned to throw buckets of sheep's blood over the audience, but were prevented from doing so due to opposition from BBC lawyers[46][47] and "hardcore vegans" Extreme Noise Terror.[35][48] The performance was instead garnished by a limping, kilted, cigar-chomping Drummond firing blanks from an automatic weapon over the heads of the crowd. As the band left the stage, The KLF's promoter and narrator Scott Piering announced over the PA system that "The KLF have now left the music business". Later in the evening the band dumped a dead sheep with the message "I died for you – bon appetit" tied around its waist at the entrance to one of the post-ceremony parties.[48]

Reactions were mixed. Piers Morgan, writing in The Sun, under the headline "KLF's Sick Gun Stunt Fails To Hit The Target", called The KLF "pop's biggest wallies"[49] and producer Trevor Horn is reported to have called their antics "disgusting".[48] NME, on the other hand, said that The KLF "stormed" the show and that after their performance the BRITs show went "downhill all the way".[47]

Scott Piering's PA announcement of The KLF's retirement was largely ignored at the time. NME, for example, assured their readers that the tensions and contradictions would continue to "push and spark" The KLF and that more "musical treasure" would be the result, but they noted: "[Drummond has] himself nicely skewered on the horns of an almighty dilemma. He has taken over pop music and it has been a piece of piss to do so. And he hates that. He wants to be separate from a music industry that clasps him ever closer to its bosom. He loves being in the very belly of the beast, yet he wishes he was something that'd cause it to throw up too. He wants not only to bite the hand that feeds but to shove it into an industrial mincer and stomp the resultant pulp into the dirt, yet pop, as long as you continue to make it money, would let you sexually abuse its grandmother. There is, Bill old boy, no sensible way out."[48]

In the weeks following the BRITs performance, The KLF continued working with Extreme Noise Terror on the album The Black Room,[35] but it was never finished. On 14 May 1992, The KLF announced their immediate retirement from the music industry and the deletion of their entire back catalogue:

We have been following a wild and wounded, glum and glorious, shit but shining path these past five years. The last two of which has [sic] led us up onto the commercial high ground—we are at a point where the path is about to take a sharp turn from these sunny uplands down into a netherworld of we know not what. For the foreseeable future there will be no further record releases from The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu, The Timelords, The KLF and any other past, present and future name attached to our activities. As of now all our past releases are deleted .... If we meet further along be prepared ... our disguise may be complete.[44][50]

In a comprehensive examination of The KLF's announcement and its context, Select called it "the last grand gesture, the most heroic act of public self destruction in the history of pop. And it's also Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty's final extravagant howl of self disgust, defiance and contempt for a music world gone foul and corrupt."[35] Many of The KLF's friends and collaborators gave their reactions in the magazine. Movie director Bill Butt said that "Like everything, they're dealing with it in a very realistic way, a fresh, unbitter way, which is very often not the case. A lot of bands disappear with such a terrible loss of dignity". Scott Piering said that "They've got a huge buzz off this, that's for sure, because it's something that's finally thrilling. It's scary to have thrown away a fortune which I know they have. Just the idea of starting over is exciting. Starting over on what? Well, they have such great ideas, like buying submarines". Even Kenny Gates, who as a director of The KLF's distributors APT stood to lose financially from the move, called it "Conceptually and philosophically ... absolutely brilliant". Mark Stent reported the doubts of many when he said that "I [have] had so many people who I know, heads of record companies, A&R men saying, 'Come on, It's a big scam.' But I firmly believe it's over". "For the very last spectacularly insane time", the magazine concluded, "The KLF have done what was least expected of them".

The final KLF Info sheet discussed the retirement in a typically offbeat fashion, and asked "What happens to 'Footnotes in rock legend'? Do they gather dust with Ashton Gardner and Dyke, The Vapors, and the Utah Saints, or does their influence live on in unseen ways, permeating future cultures? A passing general of a private army has the answer. 'No', he whispers 'but the dust they gather is of the rarest quality. Each speck a universe awaiting creation, Big Bang just a dawn away'."[51]

There have been numerous suggestions that in 1992 Drummond was on the verge of a nervous breakdown.[35][52][53] Drummond himself said that he was on the edge of the "abyss".[54] BRIT Awards organiser Jonathan King had publicly endorsed The KLF's live performance, a response which Scott Piering cited as "the real low point".[35] The KLF's BRITs statuette for "Best British Group" of 1992 was later "found" buried in a field near Stonehenge.[55]

K Foundation and post-retirement projects

The K Foundation was an arts foundation established by Drummond and Cauty in 1993 following their 'retirement' from the music industry. From 1993 to 1995 they engaged in a number of art projects and media campaigns, including the high-profile K Foundation art award (for the "worst artist of the year").[56][57] Most notoriously, they burnt what was left of their KLF earnings—a million pounds in cash—and filmed the performance.[58][59][60]

In 1995, Drummond and Cauty contributed a song to The Help Album as The One World Orchestra ("featuring The Massed Pipes and Drums of the Children's Free Revolutionary Volunteer Guards").[61] "The Magnificent" is a drum'n'bass version of the theme tune from The Magnificent Seven, with vocal samples from DJ Fleka of Serbian radio station B92: "Humans against killing... that sounds like a junkie against dope".

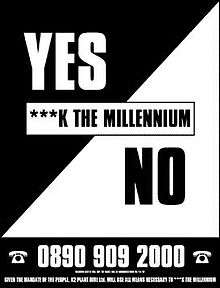

On 17 September 1997, ten years after their debut album 1987, Drummond and Cauty re-emerged briefly as 2K.[62] 2K made a one-off performance at London's Barbican Arts Centre with Mark Manning, Acid Brass, the Liverpool Dockers and Gimpo;[63] a performance at which "Two elderly gentlemen, reeking of Dettol, caused havoc in their motorised wheelchairs. These old reprobates, bearing a grandfatherly resemblance to messrs Cauty and Drummond, claimed to have just been asked along."[64] The song performed at the Barbican—"Fuck the Millennium" (a remix of "What Time Is Love?" featuring Acid Brass and incorporating elements of the hymn "Eternal Father, Strong to Save")—was also released as single. These activities were accompanied by the usual full page press adverts, this time asking readers "***k The Millennium: Yes/No?" with a telephone number provided for voting. At the same time, Drummond and Cauty were also K2 Plant Hire, with plans to build a "People's Pyramid" from used house bricks; this plan never reached fruition.[65][66]

As of 2010, Drummond continues to work as a writer and conceptual artist, with occasional appearances on radio and television. Cauty has been involved in several post-KLF projects including the music and conceptual art collective Blacksmoke and, more recently, numerous creative projects with the aquarium and the L-13 Light Industrial Workshop based in Clerkenwell, London.

KLF Communications

From their very earliest releases as The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu until their retirement in 1992, the music of Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty was independently released in their home country (the UK).[67] Their debut releases—the single "All You Need Is Love" and the album 1987—were released under the label name "The Sound Of Mu(sic)". However, by the end of 1987 Drummond and Cauty had renamed their label to "KLF Communications" and, in October 1987, the first of many "information sheets" (self written missives from The KLF to fans and the media) was sent out by the label.[68]

KLF Communications releases were distributed by Rough Trade Distribution (a spinoff of Rough Trade Records) in the South East of England, and across the wider UK by the Cartel. As Drummond and Cauty explained, "The Cartel is, as the name implies, a group of independent distributors across the country who work in conjunction with each other providing a solid network of distribution without stepping on each other's toes. We are distributed by the Cartel."[69] When Rough Trade Distribution collapsed in 1991 it was reported that they owed KLF Communications £500,000.[70] (In the same feature it was reported that Drummond wished to sign Ian McCulloch to the label, but this never happened.) Plugging (the promotion to TV and radio) was handled by longtime associate Scott Piering.[69]

Outside the UK, KLF releases were issued under licence by local labels. In the USA, the licensees were Wax Trax (the Chill Out album[71]), TVT (early releases including The History of The JAMs a.k.a. The Timelords[72]), and Arista Records (The White Room and singles[73][74]).

The KLF Communications catalogue remains deleted in the United Kingdom.

2017 reunion

On 5 January 2017, the Eastfolk Chronicle reported on the reunion of the duo, with the duo having "issued an official communication announcing a return to activity after a break of 23 years;" a poster in Hackney, London that was spotted by the newspaper's editor Cally Callomon, who is also manager for Drummond, with the heading "2017: What the Fuck Is Going On?", announces a return for the duo as The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu on 23 August 2017, and asks those seeking further information to contact K2 Plant Hire Ltd.[75] K2 has been registered in Drummond and Cauty's names at Companies House.[76]

Themes

Several threads and themes unify the many incarnations of Drummond and Cauty's creative partnership. Mostly these are esoteric or opaque in nature, which has led some people to compare Drummond and Cauty's incarnations to The Residents for their antics, if not their music.[77][78] Drummond and Cauty have also been compared to Stewart Home and the Neoists.[79] Home himself said that the duo's work "has much more in common with the Neoist, Plagiarist and Art Strike movements of the nineteen-eighties than with the Situationist avant-garde of the fifties and sixties." Drummond and Cauty "represent a vital and innovative strand within contemporary culture", he added.[80]

Illuminatus!

Drummond and Cauty made heavy references to Discordianism, a modern chaos-based religion originally described by Malaclypse the Younger in Principia Discordia, but popularised by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson in the Illuminatus! books, written between 1969 and 1971. The attitude and tactics of Drummond and Cauty's partnership matched that of the fictional cult whose name they had adopted. Throughout the partnership, these tactics were often interpreted by media commentators as "Situationist pranks" or "publicity stunts".[81] However, according to Drummond, "That's just the way it was interpreted. We've always loathed the word scam. I know no-one's ever going to believe us, but we never felt we went out and did things to get reactions. Everything we've done has just been on a gut level instinct."[82] Cauty has expressed similar feelings, saying of The KLF, "I think it worked because we really meant it".[59]

In addition to resembling the fictional JAMs' attitude and tactics, references to themes of Discordianism and Illuminatus! also manifested Drummond and Cauty's musical, visual and written work, meticulously and often covertly.

The JAMs' debut single "All You Need Is Love" includes the words "Immanentize the Eschaton!", in reference to the opening line of Illuminatus!, "They immanentized the Eschaton", interpreted as "they brought about the end of the world" or "they brought heaven to Earth". In The JAMs' "The Porpoise Song", from the album Who Killed The JAMs?, King Boy D and a talking porpoise converse, referencing Howard, the talking porpoise in Illuminatus!. The KLF's single version of "Last Train to Trancentral" opens with the demand "Okay, everybody lie down on the floor and keep calm", which is also taken from Illuminatus!.

The refrain "All bound for Mu Mu land", from The KLF's "Justified & Ancient (Stand by The JAMs)" is a reference to the Lost Continent of Mu, which Shea and Wilson identify with the fictional land Lemuria in Illuminatus!. At the end of the "Justified & Ancient" music video, The KLF exit in a submarine.

Drummond and Cauty's output is also highly self-referential, in common with Illuminatus!. In particular, original vocal samples are reused in a variety of musical contexts. For example, the ring modulated "Mu Mu!" sample that first appeared on "Burn the Bastards" is also to be found on "What Time Is Love? (Live at Trancentral), "Last Train to Trancentral (Live from the Lost Continent)" and "Fuck the Millennium".

The number 23, significant within numerology, is a theme of Illuminatus!, where instances of the number are both overtly and surreptitiously placed. Similarly, an abundance of such occurrences were deposited throughout Drummond and Cauty's collective output, for example:

- In lyrics to the song "Next" from the album 1987: "23 years is a mighty long time".

- In periods of time: for instance, they reportedly signed a contract preventing either of them from publicly discussing the burning of a million pounds for a period of 23 years;[83] their 1997 return as 2K was "for 23 minutes only".[84]

- In numbering schemes: for instance, the debut single "All You Need Is Love" took the catalogue number JAMS 23, while the final KLF Communications Information Sheet was numbered 23; and Cauty's Ford Galaxie police car had on its roof the identification mark 23.

- In significant dates during their work: for instance, a rare public appearance by The KLF, at the Liverpool Festival of Comedy, was on 23 June 1991; they announced the winner of the K Foundation award on 23 November 1993;[85] and they burned one million pounds on 23 August 1994.[60]

When questioned on the importance that he attaches to this number, Drummond has been evasive, responding enigmatically "I know. But I'm not going to tell, because then other people would have to stop having to wonder and the thing about beauty is for other people to wonder at it. It's not very beautiful once you know".[86] Drummond's penchant for living by numbers has also been observed in his choosing to align the ages at which he undertook creative projects The Man and 45 with the standard revolution speeds of a turntable (33.3 and 45 rpm).

The "Pyramid Blaster"[40] is a logo and icon frequently and prominently depicted within the duo's collective work: a pyramid, in front of which is suspended a ghetto blaster displaying the word "Justified". This references the All-Seeing Eye icon, often depicted as an eye within a triangle or pyramid, a significant symbol of Illuminatus!. The pyramid was also a theme of the duo's 1997 re-emergence, with the proposed building by K2 Plant Hire of "a massive pyramid containing one brick for every person born in the UK during the 20th century".[87]

There is no definitive explanation of The KLF's name, nor of the origin of 'K' in the names of the K Foundation and 2K, although it is widely believed that the correct spelling was "Kopyrite" in order for the full title to comprise 23 letters. KLF has been variously reported as being an initialism for "Kopyright Liberation Front",[88] and "Kings of the Low Frequencies". This mirrors Illuminatus!, where the fictional JAMs are in alliance with The LDD – who regularly change the origins of their name – and The ELF ("Erisian Liberation Front").

Although Drummond accounted for the adoption of The JAMs name in the first KLF Communications Info Sheet,[68] the reasoning behind Drummond and Cauty's decision to reference the Illuminatus! mythology with such consistent intricacy is unknown. Indeed, it has been suggested by journalist Steven Poole that the public's inability to fully understand The KLF results in all their subsequent activities (as a partnership or otherwise) being absorbed into The KLF's mystique. In a review of Drummond's 1999 book, 45, and an appraisal of The KLF's career, Poole stated that "[Bill Drummond] and collaborator Jimmy Cauty are the only true conceptual artists of the [1990s]. And for all the eldritch beauty of their art, their most successful creation is the myth they have built around themselves."[89] He concluded,

A myth like The KLF's is peculiarly omnivorous. Just as there can never be any evidence to disprove a conspiracy theory because the fabrication of such evidence – don't you see? – is itself part of the conspiracy, so the pop myth of The KLF can never be blown apart by anything they do, no matter how dumb or embarrassing. The myth will suck it up, like a black hole.

Trancentral, eternity, sheep

Trancentral (aka the Benio[90]) was the operations centre of The KLF, their mythological home, and their studios. Despite the grandiose lyrics of "Last Train to Trancentral", Trancentral was in fact Cauty's residence in Stockwell, South London (51°28′17″N 0°07′41″W / 51.471373°N 0.128167°W), "a large and rather grotty squat" according to Melody Maker's David Stubbs: "Jimmy has lived [there] for 12 years. ('I hate the place. I've no alternative but to live here.') There's little evidence of fame or fortune. The kitchen is heated by means of leaving the three functioning gas rings on at full blast until the fumes make us all feel stoned .... And, pinned just above a working top cluttered with chipped mugs is a letter from a five-year-old fan, featuring a crayon drawing of the band."[77]

Eternity is a recurring theme in song titles ("3 a.m. Eternal", "Madrugada Eterna") and lyrics. Drummond and Cauty also asserted that 'Eternity' was the author of an ambiguous, far-reaching contract offered to The JAMs.[40] (See The KLF films: The White Room.)

Following the February 1990 release of Chill Out, sheep had recurring roles in the duo's output until their 1992 retirement.[48] Drummond has claimed that the use of sheep on the Chill Out cover was intended to evoke contemporary rural raves[26] and the cover of the Pink Floyd album Atom Heart Mother,[91] insisting that the dead sheep gesture at the BRIT Awards was a compromise, replacing his earlier intention to literally cut off his hand at the ceremony.[60] Sheep feature in The KLF ambient video Waiting, and some sheep were guests of honour at the first screening of The KLF's ultimately unreleased film The White Room. It is unclear whether the theme of sheep had any particular artistic meaning. Indeed, the inner sleeve of The White Room CD pictured Drummond and Cauty each holding a sheep, with the caption "Why sheep?".

Ceremonies and journeys

Drummond and Cauty's work often involved notions of ceremony and journey. Journeys are the subject of the KLF Communications recordings Chill Out, Space, "Last Train to Trancentral", "Justified & Ancient" and "America: What Time Is Love?", as well as the aborted film project The White Room. The Chill Out album depicts a journey across the U.S. Gulf Coast. In his book 45, Drummond expressed his admiration for the work of artist Richard Long, who incorporates physical journeys into his art.[92]

Fire and sacrifice were recurring ceremonial themes: Drummond and Cauty made fires to dispose of their illegal debut album and to sacrifice The KLF's profits; their dead sheep gesture of 1992 carried a sacrificial message. The KLF's short film The Rites of Mu depicts their celebration of the 1991 summer solstice on the Hebridean island of Jura: a 60-foot (18 m) tall wicker man was burnt at a ceremony in which journalists were asked to wear yellow and grey robes and join a chant.[86] Chanting also featured in "3 a.m. Eternal", Chill Out, a football chant was incorporated into "Doctorin' the Tardis" and – aggressively – chanting was used in "Fuck the Millennium".

Promotion

Drummond and Cauty's promotional tactics were unconventional. The duo were renowned for their distinctive and humorous public appearances (including several on Top of the Pops), at which they were often costumed.[77][93] They granted few interviews, communicating instead via semi-regular newsletters, or cryptically phrased full-page adverts in UK national newspapers and the music press. Such adverts were typically stark, comprising large white lettering on black. A single typeface became characteristic of all KLF Communications' and K Foundation output, being used almost exclusively on sleevenotes and record labels, merchandise and adverts.

From the outset of their collaborations, Drummond and Cauty practised the guerrilla communication tactic that they described as "illegal but effective use of graffiti on billboards and public buildings" in which "the original meaning of the advert would be totally subverted".[20] Much as The JAMs' early recordings carried messages on the back of existing musical works, their promotional graffiti often derived its potency from the context in which it was placed. For instance, The JAMs' "SHAG SHAG SHAG" graffiti, coinciding with their release of "All You Need Is Love", was drawn over the "HALO HALO HALO" slogan of a Today billboard that depicted Greater Manchester Police Chief Constable James Anderton,[18] who had decried homosexuals amidst the UK media's AIDS furore.[94]

Music press journalists were occasionally invited to witness the defacements. In December 1987, a Melody Maker reporter was in attendance to see Cauty reverse his car Ford Timelord alongside a billboard and stand on its roof to graffiti a Christmas message from The JAMs.[24] In February 1991, another Melody Maker journalist watched The KLF deface a billboard advertising The Sunday Times, doctoring the slogan "THE GULF: the coverage, the analysis, the facts" by painting a 'K' over the 'GU'. Drummond and Cauty were, on this occasion, caught at the scene by police and arrested, later to be released without charge.[77]

In November 1991, the slogan "It's Grim Up North" appeared as graffiti on the junction of London's M25 orbital motorway with the M1, which runs to Northern England. The graffiti, for which The JAMs denied responsibility, led to a House of Commons motion being timetabled by Member of Parliament Joe Ashton regarding regional imbalance.[95] In September 1997, on the day after Drummond and Cauty's brief remergence as 2K, the graffiti "1997: What The Fuck's Going On?" appeared on the outside wall of London's National Theatre, ten years after the slogan "1987: What The Fuck's Going On?" had been similarly placed to mark the release of The JAMs' debut album.[96]

Legacy

Despite their protestations of 1988 about not wishing to be seen as crusaders for sampling,[36] The JAMs continue to be associated with the cultural movement which retrospectively bundles together those literary and artistic works that make use of "creative plagiarism". 1987: What the Fuck Is Going On? is considered a landmark work in the early history of sampling music in the United Kingdom. (See mashup.)

Similarly, Chill Out is cited as "one of the essential ambient albums".[97] In 1996, Mixmag named Chill Out the fifth best "dance" album of all time, describing Cauty's DJ sets with The Orb's Alex Paterson as "seminal".[98] The Guardian has credited The KLF with inventing "stadium house"[99] and NME named The KLF's stadium house album The White Room the 81st best album of all time.[100][101] Elements of The KLF's stadium house concept (sampled crowd noise, and signatory vocal samples reused on different songs) were adopted by several other rave acts of the early 1990s, including Scooter, Utah Saints, N-Joi and Messiah.

Sound on Sound magazine credited The KLF with "set[ting] the trend for a new approach to mixing". Engineer Mark Stent is quoted as saying:

It was in working with Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty that things really started to happen in a new way, using mixing as a work-in-progress, rather than an end stage. We were running everything live in the studio, from sequencers and samplers. Obviously there was also stuff on tape, but they would come in with their Ataris and Akai samplers, and we would end up rearranging the whole song whilst mixing things. They would then take away what we did, work on it again, and come back a while later, and I'd mix stuff again. My KLF work put me in the picture, and after that the phone never stopped ringing.— [102]

Opinions of contemporaries

In 1991, Chris Lowe of Pet Shop Boys said that he considered the only other worthwhile group in the UK to be The KLF. Neil Tennant added that "They have an incredibly recognisable sound. I liked it when they said EMF nicked the F from KLF.[103] They're from a different tradition to us in that they're pranksters and we've never been pranksters."[43]

At the time of The KLF's retirement announcement, Drummond's old friend and colleague David Balfe said of Drummond's KLF career that "the path he's trod[den] is a more artistic one than mine. I know that deep down I like the idea of building up a very successful career, where Bill is more interested in weird stuff .... I think the very avoidance of cliché has become their particular cliché".[35]

In March 1994, members of the anarchist band Chumbawamba expressed their respect for The KLF. Vocalist and percussionist Alice Nutter referred to The KLF as "real situationists" categorising them as political musicians alongside the Sex Pistols and Public Enemy. Dunst Bruce lauded the K Foundation, concluding "I think the things The KLF do are fantastic. I'm a vegetarian but I wish they'd sawn an elephant's legs off at the BRIT Awards."[104]

Direct influence

The KLF have been imitated to some degree by German techno band Scooter, being sampled on virtually every album Scooter have released. KLF were themselves apparently the victims of a "hoax" when an outfit called "1300 Drums featuring the Unjustified Ancients of M.U." released a novelty single to cash-in on the popularity of Manchester United footballer Eric Cantona. 1300 Drums even made a KLF-style Top of the Pops appearance, with the "band" wearing Cantona masks. The authorship of "Ooh Aah" remains unresolved: at least one source maintains that Drummond and Cauty themselves were 1300 Drums.[105]

The Timelords' book, The Manual, was reportedly used by the one-hit-wonders Edelweiss to secure their hit "Bring Me Edelweiss".[106][107]

"Last Train to Trancentral" was used in the finale of Blue Man Group's theatrical shows for 20 years before being replaced and was covered by them on an EP. The group's Rock Concert Instruction Manual is a tribute to The Manual.

In June 2014 the Classic Pop magazine website featured an article which claimed The KLF were in turn influenced by the Dr Calculus mdma 1986 album Designer Beatnik.[108]

Career retrospectives

Drummond and Cauty have made frequent appearances in the British broadsheets and music papers since The KLF's retirement, most often in connection with the K Foundation and their burning of one million pounds. It is worth noting that The KLF in their various incarnations have been to an extent "media darlings" who have received largely unqualified praise from the printed media. The NME described them as "Masters of manipulating media and perceptions of themselves".[109]

In 1992, NME referred to The KLF as "Britain's greatest pop group" and "the two most brilliant minds in pop today",[48] and in 2002 listed the duo in their "Top 50 Icons" at number 48.[110] The British music paper also listed The KLF's 1992 BRIT Awards appearance at number 4 in their "top 100 rock moments of all time".[111] "What's unique about Drummond and Cauty", the paper said in 1993, "is the way that, under all the slogans and the sampling and the smart hits and the dead sheep and the costumes, they appear not only to care, but to have some idea of how to achieve what they want."[8]

"[Of their many aliases,] it is as the KLF that they will go down in pop history," wrote Alix Sharkey in 1994, "for a variety of reasons, the most important being the resolute purity of their self-abnegation, and their visionary understanding of pop." He added: "By early 1992 the KLF was easily the best-selling, probably the most innovative, and undoubtedly the most exhilarating pop phenomenon in Britain. In five years it had gone from pressing up 500 copies of its debut recording to being one of the world's top singles acts." The same piece also quoted Sheryl Garratt, editor of The Face: ""the music hasn't dated. I still get an adrenaline rush listening to it." Garratt believes their influence on the British house and rap scene cannot be overestimated. "Their attitude was shaped by the rave scene, but they also love pop music. So many people who make pop actually despise it, and it shows.""[112]

In a largely cynical piece, Trouser Press reviewer Ira Robbins referred to The KLF's body of work as "a series of colorful sonic marketing experiments".[10] The Face called them "the kings of cultural anarchy".[113]

In 2003, The Observer named The KLF's departure from the music business (and the BRITs performance in which the newspaper says "their legend was sealed") the fifth greatest "publicity stunt" in the history of popular music (Elvis joining the army being hailed as the greatest).[114] A 2004 listener poll by BBC 6 Music saw The KLF/K Foundation placed second in a list of "rock excesses" (after The Who).[115]

Instrumentation

Early releases by The JAMs, including the album 1987, were performed using an Apple II computer with a Greengate DS3 sampler peripheral card, and a Roland TR-808 drum machine.[116][117] On later releases, the Greengate DS3 and Apple II were replaced with an Akai S900 sampler and an Atari computer respectively.[102] The house music of Space and The KLF involved much original instrumentation, for which the Oberheim OB-8 analogue synthesiser was prominently used.[118] Of the two Oberheims The KLF used, only one remains. It is now owned by James Fogarty (with whom Cauty founded Blacksmoke).

The KLF's 1990–1992 singles were mixed by Mark Stent, using a Solid State Logic (S.S.L.) automated mixing desk, and The White Room LP mixed by J. Gordon-Hastings using an analogue desk. The SSL is referenced in the subtitle of The KLF single "3 a.m. Eternal (Live at the S.S.L.)". The Roland TB-303 bassline and Roland TR-909 drum machine feature on "What Time Is Love (Live at Trancentral)".[118]

Several of Drummond and Cauty's compositions feature distinctive original instrumentation using non-synthesised instruments. Drummond played a Gibson ES-330 semi-acoustic guitar on "America: What Time Is Love?",[119] and Cauty played electric guitar on "Justified & Ancient (Stand by The JAMs)" and "America: What Time Is Love?". Graham Lee provided prominent pedal steel contributions to The KLF's Chill Out and "Build a Fire". Duy Khiem played clarinet on "3 a.m. Eternal" and "Make It Rain".[118] The KLF track "America No More" features a pipe band,[119] and 2K's "Fuck The Millennium" incorporates a full brass band.

Discography

- The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu: 1987 (What the Fuck Is Going On?) (The Sound of Mu(sic), 1987)

- The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu: Who Killed The JAMs? (KLF Communications, 1988)

- The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu/The KLF/The Timelords: Shag Times (KLF Communications, 1988)

- The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu/The KLF/The Timelords: The History of The JAMs a.k.a. The Timelords (TVT Records, 1989)

- The KLF/Various Artists: The "What Time Is Love?" Story (KLF Communications, 1989)

- The KLF: Chill Out (KLF Communications, 1990)

- Space: Space (KLF Communications, 1990)

- The KLF: The White Room (KLF Communications, 1991)

Bibliography

- The KLF: Chaos, Magic and the Band who Burned a Million Pounds - (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2013) [120] by John Higgs

See also

References

- ↑ "The KLF |". Digitalinberlin.de. 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "the (un)real history of the pop avant-garde". Stewarthomesociety.org. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ "Incubate Blog » Blog Archive » Bill Drummond (The KLF) announced for debate and The17 project for Incubate 2011". Inlog.org. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- ↑ IMO Records. "The KLF Biography", IMO Records' Retrieved on 29 February 2011.

- 1 2 Bush, J., KLF biography, Allmusic (link)

- ↑ Reynolds, Simon, Rip It Up And Start Again: Post-punk 1978–1984, ISBN 0-571-21570-X

- ↑ "Big in Japan – Where are they now?", Q Magazine, January 1992 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 "Tate tat and arty", New Musical Express, 20 November 1993 (link Archived 4 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "Special K", GQ magazine (April 1995), quoting "a ringingly quixotic press release" issued by Drummond in 1986 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- 1 2 3 Robbins, I., "KLF", Trouser Press magazine (link Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.). Retrieved 20 April 2006.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, R., "The Man review", Sounds, 8 November 1986 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ du Noyer, P. (1986), "The Man" review, Q magazine, December (?) 1986 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ LeRoy, D., Brilliant biography, Allmusic (link)

- ↑ The production was staged by Ken Campbell's "Science Fiction Theatre of Liverpool". Ian Broudie recalled meeting Drummond during the period of time that the play was staged, in a January 1997 interview with Mixmag ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-05.). Drummond mentioned Campbell and the play in an interview by Ben Watkins, published by The Wire magazine in March 1997 ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-05.). Campbell spoke about his production in an interview given to James Nye, first published in Gneurosis 1991, available at Frogweb: Ken Campbell Archived 12 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine. . Retrieved 2 March 2006.

- ↑ Logan, B., "Arts: Gastromancy and other animals: Ken Campbell has a new show at the National Theatre—but he'd rather tell Brian Logan about dogs that talk and sucking spirits up your bottom", The Guardian (Manchester), 29 August 2000, "Guardian Features Pages" section, p14.

- ↑ BBC Radio 1 "Story Of Pop" documentary interview with Bill Drummond. First BBC broadcast believed to have been in late 1994, and was transmitted by Australian national broadcaster ABC on 1 January 2005. Transcript taken from the KLF FAQ. Archived 19 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "All You Need Is Love" review, Sounds, 14 March 1987.

- 1 2 "The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu", Sounds, 16 May 1987.

- ↑ Kelly, D., "All You Need Is Love" review, New Musical Express, 23 May 1987.

- 1 2 "The KLF Biography", KLF BIOG 012, KLF Communications, December 1990(link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Didcock, Barry, "Bitter Swede symphony", Sunday Herald (Glasgow), 21 October 2001, p4.

- ↑ News item, Sounds, 12 September 1987

- ↑ Brown, J., "Thank You For The Music", New Musical Express, 17 October 1987.

- 1 2 Smith, M., "The Great TUNE Robbery", Melody Maker, 12 December 1987 (link Archived 4 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "Whitney Joins The JAMs" review, New Musical Express, August 1987.

- 1 2 Interview with Bill Drummond by Ernie Longmire, "KLF Is Going to Rock You" X Magazine, July 1991 (link)

- ↑ Transcript of a Bill Drummond interview on "Bomlagadafshipoing" (Norwegian national radio house-music show), September 1991 (link Archived 4 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ "JAMs turn down Whitney", New Musical Express, 16 November 1991 (link Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Reviewed by NME writer James Brown in the 28 November 1987 edition.

- ↑ "Who Killed The JAMs?" review, Sounds, February 1988.

- ↑ "Style Icons: H.P. Baxxter on The KLF". http://www.electronicbeats.net. Electronic Beats. 2013. Retrieved April 16, 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 Bill Drummond interviewed by Richard Skinner on Saturday Sequence, BBC Radio 1, December 1990 (MP3) Archived 24 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, R., "...Ford Every Scheme", Sounds, 28 May 1988 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ ,"Doctorin' the Tardis" review, Melody Maker, 28 May 1988 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Who Killed The KLF?", Select, July 1992 (link Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- 1 2 Drummond, B., KLF Communications Info Sheet, 22 January 1988 (link Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Rimmer, L., "T in the Park: Greatest festival stories ever...", Scotland on Sunday (Edinburgh) ISSN 0955-8756 , EG MAGAZINE Edition, 8 July 2001, p7. Video Archived 18 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Mellor, C. "Beam Me Up, Scotty – How to have a number one (The JAMs way)", Offbeat Magazine, February 1989 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Sleevenotes, Indie Top 20 Volume 8, published by Beechwood Music, catalogue number TT08, 1990.

- 1 2 3 4 KLF Communications, "Information Sheet Eight", August 1990 (link Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Prendergast, Mark (2003). The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Moby-The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. pp. 407–412. ISBN 1-58234-323-3.

- ↑ "History Rewritten: The KLF biography", sleevenotes, Mu, EMI Japan TOCP-6916, October 1991 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- 1 2 Brown, J., "The Pet Shop Boys Versus The World", New Musical Express, 25 25 May 1991.

- 1 2 "Timelords gentlemen, please!", New Musical Express, 16 May 1992 (link Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ McCormick, N., "The Arts: My name is Bill, and I'm a popaholic", The Daily Telegraph (London), 2 March 2000, p27.

- ↑ "Brits behaving badly", BBC News Online, 4 March 2000 (link Archived 15 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 "Baa-nned!! KLF sheep chopped by BBC", New Musical Express, 22 February 1992 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kelly, D. "Welcome To The Sheep Seats", New Musical Express, 29 February 1992 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "KLF's Sick Gun Stunt Fails To Hit The Target", The Sun, 13 February 1992 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ KLF Communications advertisement in New Musical Express, 16 May 1992.

- ↑ KLF Communications Information Sheet #23, May 1992 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Shaw, W., "Special K", GQ magazine, April 1995 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "[1992] had been the year of Bill's 'breakdown', when The KLF, perched on the peak of greater-than-ever success, quit the music business, (toy) machine gunned the tuxedo'd twats in the front row of that year's BRIT Awards ceremony and dumped a sheep's carcass on the steps at the after-show party." Martin, G., "The Chronicled Mutineers", Vox, December 1996 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Drummond, Bill and Mark Manning, Bad Wisdom (ISBN 0-14-026118-4)

- ↑ "BRITs statuette dug up", Q magazine, Feb 1993 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "The Best Of Artists, The Worst of Artists", New York Times, 29 November 1993 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Ellison, M. "Terror strikes at the Turner Prize / Art at its very best (or worst)", The Guardian, 24 November 1993 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Reid, J., "Money to burn", The Observer, 25 September 1994. This article is a first-hand account by freelance journalist Jim Reid, the only independent witness to the burning. (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 Butler, B., interview with Jimmy Cauty for The Big Issue Australia, 18 June 2003 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.). For Cauty's actual words—a breakdown of The KLF's earnings and spending—see K Foundation Burn a Million Quid.

- 1 2 3 "Burning Question", The Observer, 13 February 2000 (link Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Discogs.com entry for "One World Orchestra, The" (discogs.com link Archived 15 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Flint, C. "Media Pranksters KLF Re-emerge As 2K", Billboard, 2 September 1997 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "Justified and (Very) Ancient?", Melody Maker, 20 August 1997 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ 2K press release & biography on the website of their record label, Mute/Blast First (link Archived 27 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "People's Pyramid", Melody Maker, 15 November 1997 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "2K: Brickin' it!", New Musical Express, Nov 97 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ KLF Communications profile at Discogs.com (link Archived 15 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 Drummond, B. (1987), KLF Info Sheet Oct 1987 (link Archived 11 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 Drummond, B. & Cauty, J. (1989) The Manual (How To Have a Number One The Easy Way), KLF Publications (KLF 009B), UK. ISBN 0-86359-616-9. (Link to full text) Archived 5 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "KLF chase money ... and McCulloch", New Musical Express, 29 February 1992 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Allmusic review of Chill Out (link)

- ↑ Allmusic review of The History of The JAMs a.k.a. The Timelords (link)

- ↑ Allmusic review of The White Room/Justified & Ancient (link)

- ↑ Bill Drummond explained the licensing situation—and inducements made by Arista—in an interview by Ernie Longmire, X Magazine, July 1991 (link)

- ↑ Doran, John (5 January 2017). "KLF Announce Return After 23 Year Absence". The Quietus. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ↑ https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/company/03013255

- 1 2 3 4 Stubbs, D. "Pranks for the Memory", Melody Maker, 16 February 1991 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ In his book 45 (Little & Brown, ISBN 0-316-85385-2 / Abacus, ISBN 0-349-11289-4), Drummond documented his love of The Residents as a concept (link).

- ↑ Extract from a feature on Stewart Home. Cornwell, J. i-D Magazine, Nov 1993 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Home, S., "Doctorin' Our Culture", published on the website of The Stewart Home Society (link Archived 14 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Vincentelli, Elisabeth (2004) ABBA gold Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Morton, R., "One Coronation Under A Groove", New Musical Express, 22 January 1991 (link Archived 4 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ K Foundation, "Cape Wrath" advertisement, in The Guardian (G2), 8 December 1995(link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ 2K press advert (link Archived 27 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine., overview Archived 27 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "K-Foundation nailed", New Musical Express, 11 December 1993 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- 1 2 "Freak Show", i-D magazine, December 1994 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Fortean Times, referencing The Big Issue, 15 September 1997 and The Guardian, 5 November 1997 (link Archived 4 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Strong, Martin C. (1999) The Great Alternative & Indie Discography, Canongate, ISBN 0-86241-913-1, p. 356

- ↑ Poole, S., "Hit man, myth maker—45", The Observer, 26 February 2000 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Mead, H. (1990), Chill Out review, New Musical Express (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Drummond, Bill. 17. Beautiful Books. p. 410. ISBN 978-1-905636-26-6.

- ↑ Drummond, B., "A Smell Of Money Under Ground", 45, Little & Brown, ISBN 0-316-85385-2 / Abacus, ISBN 0-349-11289-4, 2000.

- ↑ Frith, M., "The Return of The KLF", Sky, October 1997 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ For a general overview see: "The 1980s AIDS campaign", Panorama Article on the BBC website Archived 15 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved 26 April 2006. A fuller set of references are available in the article "All You Need Is Love (The JAMs song)"

- ↑ "The JAMs: centre of political interest", New Musical Express, 9 November 1991 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ "Pre-millennium tension hits new high", New Musical Express 27 September 1997 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ Bush, J., Chill Out review, Allmusic. Retrieved 6 April 2006.

- ↑ Philips, D., "50 Greatest Dance Albums: # 5", Mixmag, March 1996 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ O'Reilly, J. "The horny old devils", The Guardian, 29 August 1997 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ NME TOP 100 ALBUMS OF ALL TIME at NME, via the Wayback Machine

- ↑ nme.com - Top 100 Of All Times at NME, via the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Mark Stent, in Tingen, P. "The Work of a Top Flight Mixer", Sound on Sound magazine, January 1999 (link). Retrieved March 2006.

- ↑ Morton, R. "One Coronation Under A Groove", New Musical Express, 12 January 1991 ("Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-09-05.)

- ↑ Maconie, S., Chumbawumba interview, Select, March 1994 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ RedMuze biography of The KLF at BBC Online (link Archived 15 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Longmire, E. "KLF Is Going to Rock You" X Magazine, July 1991 (link)

- ↑ Reighley, K.B. "Hear No Evil", Seattle Weekly, 26 May 1999 (link Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Dr Calculus Vs The KLF, Classic Pop Magazine website, June 2014 (link Archived 24 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ "Fresh JAMMS? Archived 15 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.", New Musical Express, 6 September 2001

- ↑ "Top 50 NME Icons", New Musical Express. See also "Roll over, Beatles - Smiths top the pops: Oldies and goldies in hall of fame", The Guardian (Manchester), 17 April 2002, "Guardian Home Pages" section, p6.

- ↑ "Top 100 Rock Moments of All Time" Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine., NME.com. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ Sharkey, A., "Trash Art & Kreation", The Guardian Weekend, 21 May 1994 (link Archived 4 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ "K Foundation: Nailed To The Wall", The Face, January 1994 (link Archived 16 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Thompson, B. "The 10 greatest publicity stunts", The Observer, 27 September 2003 (link Archived 15 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Barnes, Anthony, "The Who top rock's hall of shame", The Independent on Sunday (London), 20 June 2004, p5.

- ↑ KLF Communications, sleevenotes, "1987: The JAMs 45 Edits", JAMS 23T, 1987.

- ↑ NME's 28 November 1987 review of The JAMs' single "Down Town" referred to them as "The Kings of The Greengate Sampler".

- 1 2 3 KLF Communications, sleevenotes, The White Room, JAMS LP6, 1991.

- 1 2 KLF Communications, sleevenotes, "America: What Time Is Love?", KLF USA4, 1992.

- ↑ Amazon: KLF

External links

- The Library of Mu – archive of press articles

- KLF Mailing List

- The KLF at AllMusic

- The KLF and Illuminatus! – including a list of their references to the number 23

- The KLF at Acclaimed Music – artist rank #373

- KLF Communications on IMDb