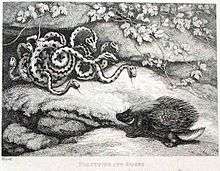

The Hedgehog and the Snake

The hedgehog and the snake, alternatively titled The snakes and the porcupine, was a fable originated by Laurentius Abstemius in 1490. From the following century it was accepted as one of Aesop's Fables in several European collections.

The ungrateful guest

The Venetian librarian Laurentius Abstemius created a Latin fable concerning a hedgehog and a viper in his Hecatomythium of 1490. In this the hedgehog begs shelter for the winter in the snake's hole. When the host suffers from its guest's prickles and asks it to leave, the hedgehog refuses, suggesting that it is for the one who is discontented with the lodging to leave it.[1]

In the following century variations of the fable appeared in several European collections and became sufficiently well known for Sir Philip Sydney to allude to it in his An Apology for Poetry.[2] By the 17th century it was being used as an example of ingratitude in moralistic works such as Christoph Murer's emblem book XL Emblemata[3] and the oil painting on copper by Jan van Kessel the Elder.[4] Another of these was included in the water features in the labyrinth of Versailles, set up by Louis XIV for the instruction of his son.[5] For this the king had been advised by the fabulist Charles Perrault, who records the fable in his work,[6] but the statues were associated at Versaille with the quatrains composed for them by Isaac de Benserade, who refers to the villain of the piece as a porcupine:

- The snake, too polite, gave the porcupine

- Permission to enter,

- But when it repented,

- “Get out yourself,” the ingrate replied.[7]

In England the fable appeared in several influential collections of Aesop's fables. Samuel Croxall's version features a porcupine and snakes and is applied in his long reflection to the injudicious choice either of friend or marriage partner.[8] Samuel Richardson's version is told of a snake and a hedgehog, with the advice that "It is not safe to join interest with strangers upon such terms as to lay ourselves at their mercy".[9]

References

- ↑ Fable 72

- ↑ Edited by R.W.Maslen, Manchester University 1973. Note 10 details some of the collections where it is ascribed to Aesop, p.123

- ↑ Emblem 36

- ↑ Christies site

- ↑ W.H.Matthews, Mazes & Labyrinths, London 1922, ch.14, figure 91

- ↑ Shanaweb

- ↑ Labyrinte de Versailles: Suivant la copie de Paris, 1734, Fable 38 p.76

- ↑ Fable 40, pp.97-9

- ↑ Æsop's fables, with instructive morals and reflections, London 1740, Fable 192, p.150