Greensboro sit-ins

| Greensboro sit-ins | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights Movement | |||

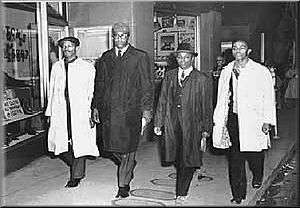

The Greensboro Four: (left to right) David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr., and Joseph McNeil | |||

| Date |

February 1 – July 25, 1960 (5 months, 3 weeks and 3 days) | ||

| Location | Greensboro, North Carolina | ||

| Caused by |

| ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

|

| |||

The Greensboro sit-ins were a series of nonviolent protests in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960,[2] which led to the Woolworth department store chain removing its policy of racial segregation in the Southern United States.[3] While not the first sit-in of the Civil Rights Movement, the Greensboro sit-ins were an instrumental action, and also the most well-known sit-ins of the Civil Rights Movement. These sit-ins led to increased national sentiment at a crucial period in US history.[4] The primary event took place at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth store, now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum.

Background

While the Greensboro sit-in was the most influential and significant sit-in of the Civil Rights Movement, it was not the first. In August 1939, black attorney Samuel Wilbert Tucker organized a sit-in at the then-segregated Alexandria, Virginia, library.[5] In 1942, the Congress of Racial Equality sponsored sit-ins in Chicago, as they did in St. Louis in 1949 and Baltimore in 1952. Also, a 1958 sit-in in Wichita, Kansas was successful in ending segregation at every Dockum Drug Store in Kansas.[6]

Plan

Days before the Woolworth sit-ins, the Greensboro Four (as they would soon be known) were debating on which way would be the best to get the media's attention. They were Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., and David Richmond. All were young black students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University.[7] They were inspired by Martin Luther King, Jr. and his practice of non-violent protest, and wanted to change the segregational policies of Woolworth in Greensboro, North Carolina. The plan was simple, but effective: the four men would occupy seats at the local Woolworth, ask to be served, and when they were inevitably denied service, they would not leave. They would repeat this process day in and day out, for as long as it would take. Their thinking was that, if they could attract widespread attention to the issue, Woolworth would feel pressured to desegregate.[7]

Events at Woolworth

.jpg)

On February 1, 1960, at 4:30pm, the four sat down at the lunch counter inside the Woolworth store at 132 South Elm Street in Greensboro.[3] The men, later also known as the A&T Four or the Greensboro Four, had purchased toothpaste and other products from a desegregated counter at the store with no problems, and then were refused service at the store's lunch counter when they each asked for a cup of coffee.[2][8][9] Following store policy, staff refused to serve the black men at the "whites only" counter and store manager Clarence Harris asked them to leave.[10] However, the four freshmen stayed until the store closed that night.

The next day, more than twenty black students, recruited from other campus groups, joined the sit-in. Students from Bennett College, a college for black women in Greensboro, also joined. White customers heckled the black students, who read books and studied to keep busy, while the lunch counter staff continued to refuse service.[9]

Newspaper reporters and a TV videographer covered the second day, and others in the community learned of the protests. On the third day, more than 60 people came to the Woolworth store. A statement issued by Woolworth national headquarters said that the company would "abide by local custom" and maintain its segregation policy.[9]

On the fourth day, more than 300 people took part. Organizers agreed to expand the sit-in protests to include the lunch counter at Greensboro's Kress store.[9]

As early as one week after the Greensboro sit-ins began, students in other North Carolina towns launched their own. Winston-Salem, Durham, Raleigh, Charlotte, and out-of-state towns such as Lexington, Kentucky all saw protests.

The sit-in movement then spread to other Southern cities, including Richmond, Virginia and Nashville, Tennessee, where students of the Nashville Student Movement were trained by civil rights activist James Lawson and had already started the process when Greensboro occurred. Most of these protests were peaceful, but there were instances of violence.[11] In Chattanooga, Tennessee, tensions rose between blacks and whites and fights broke out.[12] In Jackson, Mississippi, students from Tougaloo College staged a sit-in on May 28, 1963, recounted in the autobiography of Anne Moody, a participant. In Coming of Age in Mississippi Moody describes their treatment from whites who were at the counter when they sat down, the formation of the mob in the store and how they managed finally to leave.[13]

As the sit-ins continued, tensions grew in Greensboro. Students began a far-reaching boycott of stores with segregated lunch counters. Sales at the boycotted stores dropped by a third, leading their owners to abandon segregation policies.[3] On Monday, July 25, 1960, after nearly $200,000 in losses ($1.6 million today), store manager Clarence Harris asked three black employees to change out of their work clothes and order a meal at the counter. They were, quietly, the first to be served at a Woolworth lunch counter.[14] Most stores were soon desegregated, though in other Tennessee cities, such as Nashville and Jackson, Woolworth's continued to be segregated until around 1965, despite many protests.[9][15]

Impact

Despite the sometimes violent reaction to the sit-ins, these demonstrations eventually led to positive results. For example, the sit-ins received significant media and government attention. When the Woolworth sit-in began, the Greensboro newspaper published daily articles on the growth and impact of the demonstration. The sit-ins made headlines in other cities as well, as the demonstrations spread throughout the Southern states. A Charlotte newspaper published an article on February 9, 1960, describing the statewide sit-ins and the resulting closures of dozens of lunch counters.[16] Furthermore, on March 16, 1960, President Eisenhower expressed his concern for those who were fighting for their human and civil rights, saying that he was "deeply sympathetic with the efforts of any group to enjoy the rights of equality that they are guaranteed by the Constitution."[17][18] Also, this sit-in was a contributing factor in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

In many towns, the sit-ins were successful in achieving the desegregation of lunch counters and other public places. Nashville's students, who were already planning their sit-ins and started them a few days after the Greensboro group, attained desegregation of the downtown department store lunch counters in May, 1960.[19]

The media picked up this issue and covered it nationwide, beginning with lunch counters and spreading to other forms of public accommodation, including transport facilities, art galleries, beaches, parks, swimming pools, libraries, and even museums around the South.[20] The Civil Rights Act of 1964[21] mandated desegregation in public accommodations.

Over 70,000 people took part in the sit-ins. They even spread to northern states such as Ohio and the western state of Nevada. Sit-ins protested about segregated swimming pools, lunch counters, libraries, transport facilities, museums, art galleries, parks and beaches. By simply highlighting such practices, the students can claim to have played a significant part in the history of the Civil Rights Movement.[22]

In 1993, a four-seat portion of the lunch counter was acquired by the Smithsonian Institution.[23] The International Civil Rights Center & Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina, contains the full rest of the lunch counter in its original footprint inside the store, along with photos of the original four protesters, a timeline of the events, and headlines from the media. The street south of the site was renamed February One Place, in commemoration of the date of the first Greensboro sit-in.[24]

See also

- Sit-in movement - list of sit-in's

- American Civil Rights Movement Timeline

- February One: The Story of the Greensboro Four

References

- ↑ "The Sit-in Movement". International Civil Rights Center & Museum. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- 1 2 The Greensboro Sit-In, history, Retrieved February 25, 2015

- 1 2 3 "Greensboro Lunch Counter Sit-In", Library of Congress. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ↑ First Southern Sit-in, Greensboro NC, Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ "America's First Sit-Down Strike: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In". City of Alexandria. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Kansas Sit-In Gets Its Due at Last; NPR; October 21, 2006". Npr.org. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- 1 2 "The Greensboroina History". nchistory.web.unc.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-14.

- ↑ Wolff, Miles. Lunch at the 5 and 10. Revised & expanded. Chicago: Elephant Paperbacks, 1990. ISBN 0929587316.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Greensboro Chronology", International Civil Rights Center and Museum, Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- ↑ The Greensboro Four (PDF), North Carolina Museum of History, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-01-25, retrieved 2010-11-26

- ↑ Schlosser, James ‘Jim’ (Feb 2, 2009), "Timeline", in Prout, Teresa, Greensboro Sit-ins (news & record)

- ↑ Wolff, Miles (1970), Lunch at the Five and Ten, New York: Stein and Day.

- ↑ Moody, Anne (1968). "23". Coming of Age in Mississippi. New York: Bantam Dell.

- ↑ "Civil Rights Greensboro".

- ↑ "Timeline of civil rights in Tennessee - October 1960 - Civil Rights - A Jackson Sun Special Report". Orig.jacksonsun.com. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- ↑ Prout, Teresa, ed. (Feb 2, 2009), "NC Stores Close Down Counters", Greensboro Sit-ins (news & record)

- ↑ Wilkinson, Doris Yvonne (1969), Black Revolt: Strategies of Protest, Berkeley: McCutchan

- ↑ Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1961). "93 The President’s News Conference of March 16, 1960.". The Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States. Dwight D. Eisenhower. January 1, 1960, to January 20, 1961. Published by the Office of Federal Register National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration. p. 294.

- ↑ "The Asheboro Sit-Ins". Notes on the History of Randolph County, NC. January 18, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ↑ Sit-ins Spread Across the South, Civil Rights Movement Veterans

- ↑ Civil Rights Act, Find US law, 1964

- ↑ "Greensboro 1960 - History Learning Site". History Learning Site. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ↑ Curtis, Mary C (February 19, 2011). "Museum Will Bring African American – Make That 'American' – History to National Mall". Politics Daily. AOL. Archived from the original on February 21, 2011. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Workers unearth bits of urban history at February One Place", News & Record, September 9, 2009

Bibliography

- Wolff, Miles (1990). Lunch at the 5 and 10. Elephant Paperbacks. ISBN 0929587316.

Further reading

- Chafe, William Henry (1981). Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195029192.

- Kowal, Rebekah J. (Winter 2004). "Staging the Greensboro Sit-Ins". TDR. 48 (4): 135–154.

- Pollitt, Daniel H. (Summer 1960). "Dime Store Demonstrations: Events and Legal Problems of First Sixty Days, 1960". Duke Law Journal. 9 (1): 315–365.

- Walzer, Michael (Spring 1960). "A Cup of Coffee and a Seat". Dissent. 7: 111–120.

External links

- Civil Rights Greensboro: Greensboro sit-ins, UNCG.

- "Greensboro Lunch Counter", Object of History.

- Greensboro Sit-Ins (timeline), CRMVet.

- Greensboro 1960, UK: History learning site.

- Sit-ins (exhibit), Greensboro Historical Museum.

- "Launch of a Civil Rights Movement", Greensboro sit-ins.

- Making Equality a Reality – History of Sit ins, Core online.

- Sit-in movement, International Civil Rights Center & Museum.

- Guide to the Edward Raymond Zane Letters, Duke University.