The Fortune Hunter

The Fortune Hunter is a drama in three acts by W. S. Gilbert. The piece concerns an heiress who loses her fortune. Her shallow husband sues to annul the marriage, leaving her pregnant and taking up with a wealthy former lover. The piece was produced on tour in Britain in 1897, never playing in London.

Gilbert was the librettist of the extraordinarily successful Savoy operas, written in collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan. Their last work together was The Grand Duke, produced in 1896. Gilbert's later dramas were mostly unsuccessful, and The Fortune Hunter was no exception; its poor reception provoked Gilbert to announce retiring from writing for the stage.

Background

Beginning in 1871, Gilbert and Sullivan wrote fourteen comic operas together.[1] Most of these were tremendously popular, both in London and on tour.[2][3] Their success eclipsed Gilbert's playwriting career, during which he produced dozens of plays. While many of his comedies enjoyed success, some of his dramas, particularly the later ones, did not. After his 1888 flop, Brantinghame Hall, Gilbert vowed never to write another serious drama again.[4]

During the production of Gilbert and Sullivan's 1889 comic opera, The Gondoliers, Gilbert sued producer Richard D'Oyly Carte over expenses of the Gilbert and Sullivan partnership. Sullivan sided with Carte, and the partnership disbanded. The lawsuit left Gilbert and Sullivan somewhat embittered, although they finally collaborated on two more works.[3] The last of these was The Grand Duke, opening in March 1896. This was the least successful of the Savoy Operas, lasting for only 123 performances.[5] H. M. Walbrook suggested the reason for this, writing, "It reads like the work of a tired man... There is his manner but not his wit, his lyrical fluency but not his charm... [For] the most part, the lyrics were uninspiring and the melodies uninspired.[6] Isaac Goldberg added, "the old self-censorship [had] relaxed".[7]

By March 1897, Gilbert was ready to get back to work. He suggested to producer Richard D’Oyly Carte and his wife Helen Carte that he write a libretto for a new comic opera based on his earlier play, The Wicked World. Carte declined this offer, but years later, Gilbert followed through on this idea in Fallen Fairies. A revival of Gilbert's comic opera Princess Toto was also briefly considered, but Gilbert balked at Carte's suggested revisions.[8] Instead, Gilbert turned to writing a new contemporary drama, The Fortune Hunter, commissioned by Edward Willard. But Willard was not satisfied with Gilbert's drafts, and the manager of the St James's Theatre, who had asked Gilbert for a play, found it unsuitable. Gilbert then offered the play to May Fortescue (the original Celia in Iolanthe) for her touring company.[9] The snobs and valet in the piece are based on an 1869 Bab Ballad, "Prince Il Baleine".[10]

Synopsis

- Act I

Aboard the ship Africa, Vicomte Armand De Breville, a young and impoverished French aristocrat, is fencing with his friend Sir Cuthbert Jameson. Armand had, some time earlier, proposed marriage to a crude but wealthy American woman, Euphemia Van Zyl, but she instead married the elderly Duke of Dundee. Sir Cuthbert and Armand are both now romantically interested in another passenger, a strong-willed Australian heiress named Diana Caverel. Diana rejects Sir Cuthbert's proposal, calling him "the best, the truest, the most valued friend I have ever possessed." The Duke and Duchess of Dundee board, preceded by their courier, Barker. Two snobbish British tourists, Mr. and Mrs. Coxe-Coxe, eagerly greet Barker, thinking that he is the Duke. They lend him money to gamble under his infallible system. Euphemia sees Armand and apologises for having ill-treated him. After she leaves, he proposes to Diana, and she accepts.

- Act II

One year later, in Paris at Armand's flat, Armand discovers that Diana has no more fortune. In debt, Armand asks Lachaud, his lawyer, to annul the marriage. Under the French Civil Code, a man under the age of 25 required parental consent to marry, and Armand had only been 24. Armand goes to Naples, but says to Diana that if anything should happen to leave her "husbandless", he is "not worth weeping for." Diana loves Armand passionately. She has been worried about whether Armand loves her and feels that this statement means that he does. Sir Cuthbert then appears and mentions that Euphemia is in Naples. Diana believes that Armand is having an affair with the Duchess. Sir Cuthbert doubts that Euphemia would take up with a married man, but Diana notes that the Duchess might not know of Armand's marriage; indeed his own parents have only just been informed of it.

The Marquis and Marquise de Breville, Armand's parents, appear and question Diana. They are shocked to find out that her father was a mere merchant and state that they would have forbidden the marriage, noting that Armand was underage. A letter arrives from Armand, also stating that he was underage at the time of the wedding, and informing Diana that he is moving to annul the marriage. However, this has the unintended effect of angering Armand's parents, who balk at his dishonourable actions and state that they would not do anything to harm Diana's reputation. They declare that they will disown Armand and welcome Diana as their daughter.

- Act III

In Monte Carlo at the Duchess's villa, six months later, Euphemia decides to leave the Duke and return to America to marry Armand. Mr. and Mrs. Coxe-Coxe arrive, demanding the return of the money that they had lent to the "Duke". They are about to be arrested, but Armand explains that Barker, the person to whom they entrusted the money, was actually the Duke's courier. Armand now tells Euphemia that he is married. Although he had begun proceedings to annul the marriage, he is having second thoughts and plans to halt the proceedings. The Duchess agrees to pay Armand's debts, although she is naturally upset.

Diana arrives, and Armand discovers that she has given birth to their son. She appeals to him to stop the annulment so that their child will not suffer the stigma of bastardy. Overwhelmed by his emotions, he assures her that he is moving to halt the proceedings and begs her to take him back. No longer in love with him, she haughtily rejects him and departs.

Armand asks Lachaud to stop the application, but the lawyer says that it is too late. The only way to interrupt the proceeding is if Armand dies. He tries to poison himself, but Lachaud prevents him. Sir Cuthbert arrives and angrily accuses Armand of lying in the letter about his parents' intention to annul his marriage. He proposes to settle Armand's debts to save the marriage. Armand, seeing an opportunity, challenges Sir Cuthbert to a duel, saying that he is insulted by the accusation. Sir Cuthbert resists, but Armand enrages his friend by suggesting that it is inappropriate for Sir Cuthbert to have accompanied Diana. As they begin the duel, Armand intentionally steps into Sir Cuthbert's blade. As he dies, he declares that he himself, not Sir Cuthbert, caused his death. He asks Sir Cuthbert to care for Diana.

Production and aftermath

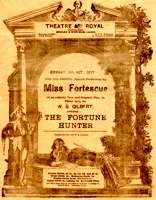

Originally produced at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham, the play opened on 27 September 1897. The first-night audience was enthusiastic, but the play's tragic ending, as well as Gilbert's treatment of Diana and his familiar theme of "woman victimized by man's double standards" (compare Charity),[11] together with his old-fashioned style, dissatisfied the critics.[12] Despite a fine production with "exquisite costumes" and excellent acting from Fortescue and others, the many critics in attendance panned the piece.[11] Nevertheless, the play did good business at the box office in Birmingham.[9]

After the short Birmingham run, as the play was moving to the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh, Gilbert gave an interview to a reporter from the Evening Despatch. The reporter, through a series of leading questions, made it seem that Gilbert had insulted various leading actor-managers of the day.[13] Gilbert also declared that he was retiring from writing for the stage[14] (although he eventually wrote a further four stage works).[15] As soon as Gilbert found out about the Despatch article, he denied that the paper had quoted him correctly. Nevertheless, the press tore into him.[13] For example, The New York Times reported Gilbert as saying: "London critics attack an author as if he was a scoundrel of the worst type, and I do not feel disposed to put myself forward as a cock-shy for these gentlemen... The fact is, managers cannot judge of a play when they see it in manuscript. If Pinero sends Irving a play, it is accepted not because it is a good play but because it is by Pinero, and if a stranger, though a clever dramatist, sends Irving or Tree, or anyone else, a play it is refused, however good, because they cannot judge of it."[14] The paper continued:

After so many years of distinguished successes as a comic opera librettist in collaboration with Sir Arthur Sullivan, Mr. Gilbert returned to serious play writing only to score a failure. His new comedy, The Fortune Hunter, which was tried upon the Birmingham public, has fallen flat. The critics are unanimous in their verdict that the play lacks the elements of strength and popularity and that no amount of carpentering, tinkering, or revising could infuse life into it. This after Mr. Gilbert had announced, seemingly without thought of the possibility of failure, that he had resolved to forswear comic opera for more important work. Now it is being recalled that he promised his public, after the disastrous Brantinghame Hall, that he would never repeat the offense.[14]

Subsequent press criticism of The Fortune Hunter was heavy. The play continued to tour for a while, and Gilbert tried several cuts and minor rewrites, but reviews continued to be poor. Because of its lack of success in the provinces, the play never opened in London and ultimately failed.[16]

In 1906 and afterwards for several years, Gilbert worked on The Fortune Hunter, rewriting it under different titles, but he did not succeed in reviving interest in the play.[17]

Gilbert's letter to The Times

The same day that the play opened in Birmingham, coincidentally, Gilbert wrote a letter to The Times (published the following day) complaining about Saturday train service on the London and North Western Railway. The Fortune Hunter may be little remembered today, but the letter is frequently quoted:[9]

In the face of Saturday the officials and the [railway] company stand helpless and appalled. This day, which recurs at stated and well-ascertained intervals, is treated as a phenomenon entirely outside the ordinary operations of nature and, as a consequence, no attempt whatever is made to grapple with its inherent difficulties. To the question, "What has caused the train to be so late?" the officials reply, "It is Saturday" – as who should say, "It is an earthquake."[18]

Roles and original cast

- The Duke of Dundee, an octogenarian peer – C. B. Clarence

- Sir Cuthbert Jameson, a middle-aged Baronet – Edmund Maurice

- The Marquis de Bréville, an aristocrat – Arthur Nerton

- Vicomte Armand de Bréville, his son – Luigi Lablache

- M. Lachaud, Armand's lawyer – George P. Hawtrey

- Mr Dusley Coxe, a snobbish British tourist – Compton Coutts

- Mr Barker, the Duke's courier – W. R. Staveley

- Mr Taylor – C. Butt

- Mr Paillard, a money-lender – C. O. Axton

- Mr McQuarris, purser of the P. and O. SS. "Africa" – Vivian Stenhouse

- Pollard, a detective – A. Clay

- Captain Munroe, of the steam yacht P. and O. SS. "Africa" – Charles Howe

- Mr McFie, the Duchess of Dundee's secretary – Howard Sturge

- Quartermaster – Charles Leighton

- The Duchess of Dundee, the Duke's young bride (née Euphemia S. Van Zyl of Chicago) – Cicely Richards

- The Marquise de Bréville, Armand's mother – Adelina Baird

- Mrs Dudley Coxe, a snobbish British tourist – Nora O'Neil

- Miss Somerton, a passenger – Regina Repton

- Miss Bailey, the Duchess's maid – A. Beauchamp

- Diana Caverel, an Australian heiress – May Fortescue

Notes

- ↑ "The Gilbert and Sullivan Operas", at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 7 June 2006, accessed 24 October 2009

- ↑ Bradley, Ian (1996). The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. Introduction, vii. ISBN 0-19-816503-X.

- 1 2 Crowther, Andrew. "The Carpet Quarrel Explained", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 28 June 1997, accessed 7 October 2009

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 252–58

- ↑ Shepherd, pp. xxviii–xxxi

- ↑ Walbrook, pp. 122–24

- ↑ Goldberg, Isaac. The Story of Gilbert and Sullivan or The 'Compleat' Savoyard, (London: John Murray, 1929), pp. 424–29

- ↑ Stedman, p. 310

- 1 2 3 Ainger, p. 369

- ↑ Stedman, pp. 26–27

- 1 2 Stedman, pp. 311–12

- ↑ Crowther, pp. 169–71

- 1 2 Stedman, p. 312

- 1 2 3 "W. S. Gilbert Complains of Unfair Critics and Says He Will Write No More Plays", The New York Times, 10 October 1897, p. 5, accessed 24 October 2009

- ↑ Crowther, Andrew. ", W. S. Gilbert Society website, accessed 11 April 2011

- ↑ Archer, William. The Theatrical 'World' of 1897, Bibliolife (2009) ISBN 0-559-89488-0

- ↑ Ainger, p. 406 and Stedman, p. 312

- ↑ The Times, 28 September 1897, p. 10

References

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan–A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514769-3.

- Crowther, Andrew (2000). Contradiction Contradicted – The Plays of W. S. Gilbert. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3839-2.

- Shepherd, Marc. "Introduction: Historical Context", The Grand Duke (piano score), New York: Oakapple Press, 2009. Linked at "The Grand Duke", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

- Stedman, Jane W. (1996). W. S. Gilbert, A Classic Victorian & His Theatre. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816174-3.

- Walbrook, H.M. (1922). Gilbert & Sullivan Opera, A History and a Comment. London: F. V. White & Co. Ltd.

- Wolfson, John (1976). Final curtain: The last Gilbert and Sullivan Operas. London: Chappell in association with A. Deutsch. ISBN 0-903443-12-0

- Synopsis of The Fortune Hunter at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

External links

- Script of The Fortune Hunter at The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

- Synopsis of The Fortune Hunter on 'Gilbert and Sullivan Archive'

- The Fortune Hunter on 'The Plays of W.S. Gilbert'

- Review of The Fortune Hunter in The Times, 28 September 1897