Clark Ashton Smith

| Clark Ashton Smith | |

|---|---|

|

Smith in 1912 | |

| Born |

January 13, 1893 Long Valley, California, United States |

| Died |

August 14, 1961 (aged 68) Pacific Grove, California, United States |

| Occupation | Short story writer, poet |

| Nationality | American |

| Genre | Horror, fantasy, science fiction |

Clark Ashton Smith (January 13, 1893 – August 14, 1961) was a self-educated American poet, sculptor, painter and author of fantasy, horror and science fiction short stories. He achieved early local recognition, largely through the enthusiasm of George Sterling, for traditional verse in the vein of Swinburne. As a poet, Smith is grouped with the West Coast Romantics alongside Ambrose Bierce, Joaquin Miller, Sterling, Nora May French, and remembered as "The Last of the Great Romantics" and "The Bard of Auburn".

Smith was one of "the big three of Weird Tales, with Robert E. Howard and H. P. Lovecraft",[1] but some readers objected to his morbidness and violation of pulp traditions. The fantasy critic L. Sprague de Camp said of him that "nobody since Poe has so loved a well-rotted corpse."[2] Smith was a member of the Lovecraft circle and his literary friendship with Lovecraft lasted from 1922 until Lovecraft's death in 1937. His work is marked by an extraordinarily rich and ornate vocabulary, a cosmic perspective and a vein of sardonic and sometimes ribald humor.

Of his writing style, Smith stated that: "My own conscious ideal has been to delude the reader into accepting an impossibility, or series of impossibilities, by means of a sort of verbal black magic, in the achievement of which I make use of prose-rhythm, metaphor, simile, tone-color, counter-point, and other stylistic resources, like a sort of incantation."[3]

Biography

Early life and education

Smith was born January 13, 1893, in Long Valley, California, of English and New England parentage. He spent most of his life in the small town of Auburn, California, living in a small cabin built by his parents, Fanny and Timeus Smith. His formal education was limited: he suffered from psychological disorders including a fear of crowds, and although admitted to high school after attending eight years of grammar school (Long Valley School, whence dates the earliest known photo of him), he never went to high school. His parents decided it was better for him to be educated at home.

However, he was an insatiable reader, and continued to teach himself after he left school. His education began with the reading of Robinson Crusoe (unabridged), Gulliver's Travels, the fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen and Madame d'Aulnoy, the Arabian Nights and (at the age of 13) the poems of Edgar Allan Poe. He read an unabridged dictionary (the 13th edition of Webster's) through, word for word, studying not only the definitions of the words but also their derivations from ancient languages. Having an extraordinary eidetic memory, he seems to have retained most or all of it.[4]

The other main course in Smith's self-education was to read the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica through at least twice.[5] Smith later taught himself French and Spanish in order to translate verse out of those languages. Smith professed to hate the provinciality of the small town of Auburn but rarely left it until he married late in life.

Early writing

His first literary efforts, at the age of 11, took the form of fairy tales and imitations of the Arabian Nights. Later, he wrote long adventure novels dealing with Oriental life. By 14 he had already written a short adventure novel called The Black Diamonds which was lost for years until published in 2002. Another juvenile novel was written in his teenaged years—The Sword of Zagan (unpublished until 2004). Like The Black Diamonds, it uses a medieval, Arabian Nights-like setting, and the Arabian Nights, like the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm and the works of Edgar Allan Poe, are known to have strongly influenced Smith's early writing, as did William Beckford's Vathek.

At age 17, he sold several tales to The Black Cat, a magazine which specialized in unusual tales. He also published some tales in the Overland Monthly in this brief foray into fiction which preceded his poetic career.

However, it was primarily poetry that motivated the young Smith and he confined his efforts to poetry for more than a decade. In his later youth, Smith made the acquaintance of the San Francisco poet George Sterling through a member of the local Auburn Monday Night Club, where he read several of his poems with considerable success. On a month-long visit to Sterling in Carmel, California, Smith was introduced by Sterling to the poetry of Baudelaire.[6]

He became Sterling's protégé and Sterling helped him to publish his first volume of poems, The Star-Treader and Other Poems, at the age of 19. Smith received international acclaim for the collection. The Star-Treader was received very favorably by American critics, one of whom named Smith "the Keats of the Pacific". Smith briefly moved among the circle that included Ambrose Bierce and Jack London, but his early fame soon faded away.

Health breakdown period

A little later, Smith's health broke down and for eight years his literary production was intermittent, though he produced his best poetry during this period. A small volume, Odes and Sonnets, was brought out in 1918. Smith came into contact with literary figures who would later form part of H.P. Lovecraft's circle of correspondents; Smith knew them far earlier than Lovecraft. These figures include poet Samuel Loveman and bookman George Kirk. It was Smith who in fact later introduced Donald Wandrei to Lovecraft. For this reason, it has been suggested that Lovecraft might as well be referred to as a member of a "Smith" circle as Smith was a member of a Lovecraft one.[7]

In 1920 Smith composed a celebrated long poem in blank verse, The Hashish Eater, or The Apocalypse of Evil which was published in Ebony and Crystal (1922).[8] This was followed by a fan letter from H. P. Lovecraft, which was the beginning of 15 years of friendship and correspondence. With studied playfulness, Smith and Lovecraft borrowed each other's coinages of place names and the names of strange gods for their stories, though so different is Smith's treatment of the Lovecraft theme that it has been dubbed the "Clark Ashton Smythos."[9]

In 1925 Smith published Sandalwood, which was partly funded by a gift of $50 from Donald Wandrei. He wrote little fiction in this period with the exception of some imaginative vignettes or prose poems. Smith was poor for most of his life and often did hard manual jobs such as fruit picking and woodcutting in order to support himself and his parents. He was an able cook and made many kinds of wine. He also did well digging, typing and journalism, as well as contributing a column to The Auburn Journal and sometimes worked as its night editor.[10]

One of Smith's artistic patrons and frequent correspondents was San Francisco businessman Albert M. Bender.

Prolific fiction-writing period

At the beginning of the Depression in 1929, with his aged parents' health weakening, Smith resumed fiction writing and turned out more than a hundred short stories between 1929 and 1934, nearly all of which can be classed as weird horror or science fiction. Like Lovecraft, he drew upon the nightmares that had plagued him during youthful spells of sickness. Brian Stableford has written that the stories written during this brief phase of hectic productivity "constitute one of the most remarkable oeuvres in imaginative literature".[11]

He published at his own expense a volume containing six of his best stories, The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies, in an edition of 1000 copies printed by the Auburn Journal. The theme of much of his work is egotism and its supernatural punishment; his weird fiction is generally macabre in subject matter, gloatingly preoccupied with images of death, decay and abnormality.

Most of Smith's weird fiction falls into four series set variously in Hyperborea, Poseidonis, Averoigne and Zothique. Hyperborea, which is a lost continent of the Miocene period, and Poseidonis, which is a remnant of Atlantis, are much the same, with a magical culture characterized by bizarreness, cruelty, death and postmortem horrors. Averoigne is Smith's version of pre-modern France, comparable to James Branch Cabell's Poictesme. Zothique exists millions of years in the future. It is "the last continent of earth, when the sun is dim and tarnished". These tales have been compared to the Dying Earth sequence of Jack Vance.

In 1933 Smith began corresponding with Robert E. Howard, the Texan creator of Conan the Barbarian. From 1933 to 1936, Smith, Howard and Lovecraft were the leaders of the Weird Tales school of fiction and corresponded frequently, although they never met. The writer of oriental fantasies E. Hoffmann Price is the only man known to have met all three in the flesh.

Critic Steve Behrends has suggested that the frequent theme of 'loss' in Smith's fiction (many of his characters attempt to recapture a long-vanished youth, early love, or picturesque past) may reflect Smith's own feeling that his career had suffered a "fall from grace":

Smith's late teens and early twenties had certainly been a heady period: he'd been taken under the wing of a personal, idol, the poet George Sterling, and his first book of poetry had brought him comparisons to Keats and Shelley. This notoriety must surely have raised his standing in his small hometown. And yet the depression found Smith without a job or viable occupation, unable to eke out a living as a poet, with girlfriends berating him for his lack of ambition. And while his turn to writing fiction did put bread on the table, he found it a very distasteful business at times—he had once said to Sterling that writing prose was "a hateful task, for a poet, and [one which] wouldn't be necessary in any true civilisation." In short, it may be that Smith experienced that variety of "let-down" or loss peculiar to the child prodigies.[12]

Mid-late career: return to poetry and sculpture

In September 1935, Smith's mother Fanny died. Smith spent the next two years nursing his father through his last illness. Timeus died in December 1937. Aged 44, Smith now virtually ceased writing fiction. He had been severely affected by several tragedies occurring in a short period of time: Robert E. Howard's death by suicide (1936), Lovecraft's death from cancer (1937) and the deaths of his parents, which left him exhausted. As a result, he withdrew from the scene, marking the end of Weird Tales' Golden Age. He began sculpting and resumed the writing of poetry. However, Smith was visited by many writers at his cabin, including Fritz Leiber, Rah Hoffman, Francis T. Laney and others.

In 1942, three years after August Derleth founded Arkham House for the purpose of preserving the work of H.P. Lovecraft, Derleth published the first of several major collections of Smith's fiction, Out of Space and Time (1942). This was followed by Lost Worlds (1944). The books sold slowly, went out of print and became costly rarities. Derleth published five more volumes of Smith's prose and two of his verse, and at his death in 1971 had a large volume of Smith's poems in press.

Later life, marriage and death

In 1953 Smith suffered a coronary attack. Aged 61, he married Carol(yn) Jones Dorman on November 10, 1954. Dorman had much experience in Hollywood and radio public relations. After honeymooning at the Smith cabin, they moved to Pacific Grove, California, where he set up a household with their children. (Carol had been married before and had three children). For several years he alternated between the house on Indian Ridge and his wife's house in Pacific Grove. Having sold most of his father's tract, in 1957 the old house burned—the Smiths believed by arson, others said by accident.

Smith now reluctantly did gardening for other residents at Pacific Grove, and grew a goatee. He spent much time shopping and walking near the seafront but despite Derleth's badgering, resisted the writing of more fiction.[13] In 1961 he suffered strokes. In August 1961 he quietly died in his sleep, aged 68. After Smith's death Carol remarried (becoming Carolyn Wakefield) and subsequently died of cancer.

The poet's ashes were buried beside, or beneath, a boulder to the immediate west of where his childhood home (destroyed by fire in 1957) stood; some were also scattered in a stand of blue oaks near the boulder. There was no marker.[14] In more recent times a plaque to his memory has been erected at the Auburn, California, Placer County Library.[15]

Bookseller Roy A. Squires was appointed Smith's "west coast executor", with Jack L. Chalker as his "east coast executor".[16] Squires published many letterpress editions of individual Smith poems.

Smith's literary estate is represented by his stepson, Prof William Dorman, director of CASiana Literary Enterprises. Arkham House owns the copyright to many Smith stories, though some are now in the public domain.

For 'posthumous collaborations' of Smith (stories completed by Lin Carter), see the entry on Lin Carter.

Artistic periods

While Smith was always an artist who worked in several very different media, it is possible to identify three distinct periods in which one form of art had precedence over the others.

Poetry: until 1925

Smith published most of his volumes of poetry in this period, including the aforementioned The Star-Treader and Other Poems, as well as Odes and Sonnets (1918), Ebony and Crystal (1922) and Sandalwood (1925). His long poem The Hashish-Eater; Or, the Apocalypse of Evil was written in 1920.

Weird fiction: 1926–1935

Smith wrote most of his weird fiction and Cthulhu Mythos stories, partially inspired by H. P. Lovecraft. Creatures of his invention include Aforgomon, Rlim-Shaikorth, Mordiggian, Tsathoggua, the wizard Eibon, and various others. In an homage to his friend, Lovecraft referred in "The Whisperer in Darkness" and "The Battle That Ended the Century" (written in collaboration with R. H. Barlow) to an Atlantean high-priest, "Klarkash-Ton."

Smith's weird stories form several cycles, called after the lands in which they are set: Averoigne, Hyperborea, Mars, Poseidonis, Zothique.[17] To some extent Smith was influenced in his vision of such lost worlds by the teachings of Theosophy and the writings of Helena Blavatsky. Stories set in Zothique belong to the Dying Earth subgenre. Amongst Smith's science fiction tales are stories set on Mars and the invented planet of Xiccarph.

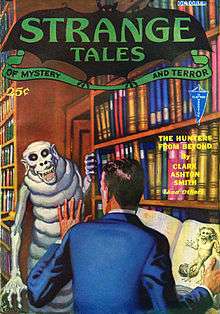

His short stories originally appeared in the magazines Weird Tales, Strange Tales, Astounding Stories, Stirring Science Stories and Wonder Stories.

Clark Ashton Smith was the third member of the great triumvirate of Weird Tales, with Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard.

Many of Smith's stories were published in six hardcover volumes by August Derleth under his Arkham House imprint. For a full bibliography to 1978, see Sidney-Fryer, Emperor of Dreams (cited below). S.T. Joshi is working with other scholars to produce an updated bibliography of Smith's work.

A selection of Smith's best-known tales includes:

- "The Last Incantation" — Weird Tales, June 1930 LW2

- "A Voyage to Sfanomoe" — Weird Tales, August 1931 LW2

- "The Tale of Satampra Zeiros" — Weird Tales November 1931 LW2

- "The Door to Saturn" — Strange Tales, January 1932 LW2

- "The Planet of the Dead" — Weird Tales, March 1932 LW2

- "The Gorgon" — Weird Tales, April 1932 LW2

- "The Letter from Mohaun Los" (under the title of "Flight into Super-Time") — Wonder Stories, August 1932 LW1

- "The Empire of the Necromancers" — Weird Tales, September 1932 LW1

- "The Hunters from Beyond" — Strange Tales, October 1932 LW1

- "The Isle of the Torturers" — Weird Tales, March 1933 LW1

- "The Light from Beyond" — Wonder Stories, April 1933 LW1

- "The Beast of Averoigne" — Weird Tales, May 1933 LW1

- "The Holiness of Azedarac" — Weird Tales, November 1933 LW1

- "The Demon of the Flower" — Astounding Stories, December 1933 LW2

- "The Death of Malygris" — Weird Tales, April 1934 LW2

- "The Plutonium Drug" — Amazing Stories, September 1934 LW2

- "The Seven Geases" — Weird Tales, October 1934 LW2

- "Xeethra" — Weird Tales, December 1934 LW1

- "The Flower-Women" — Weird Tales, May 1935 LW2

- "The Treader of the Dust" — Weird Tales, August 1935 LW1

- "Necromancy in Naat" — Weird Tales, July 1936 LW1

- "The Maze of Maal Dweb" — Weird Tales, October 1938 LW2

- "The Coming of the White Worm" — Stirring Science Stories, April 1941 LW2

Visual art: 1935–1961

By this time his interest in writing fiction began to lessen and he turned to creating sculptures from soft rock such as soapstone.[18] Smith also made hundreds of fantastic paintings and drawings.[19]

Bibliography

Books published in Smith's lifetime

- 1912: The Star-Treader and Other Poems. San Francisco: A.M. Robertson, Nov 1912. 100 pages. 2000 copies. Some copies have a frontispiece photo by Bianca Conti; others lack it.

- 1918: Odes and Sonnets. San Francisco: The Book Club of California, June 1918. 28 pages. 300 copies.

- 1922: Ebony and Crystal: Poems in Verse and Prose. Auburn CA: The Auburn Journal Press, Oct 1925. 43 pages. Limited to 500 copies signed by Smith. Some copies are found with corrections in Smith's hand to typos in the text.

- 1925: Sandalwood. Auburn CA: The Auburn Journal Press, Oct 1925. Verse. 43 pages. Limited to 250 (i.e. 225)numbered copies signed by Smith. Some copies are found with corrections in Smith's hand to typos in the text.

- 1933: The Double Shadow and Other Fantasies. Auburn, CA: The Auburn Journal Press, 1933. Short stories. Limited to 1000 copies in grey paper wrappers.

- 1937: Nero and Other Poems. Lakeport CA: The Futile Press, May 1937. 24 pages. c.250 copies. Complete copies have laid in the three page essay "The Price of Poetry", on Smith's verse, by David Warren Ryder, which was printed to accompany the book.

- 1951: The Dark Chateau and Other Poems. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, Dec 1951. 63 pages. 563 copies.

- 1958: Spells and Philtres. Sauk City: Arkham House, March 1958. Verse. 54 pages. 519 copies.

Books published posthumously

- 1962: The Hill of Dionysus – A Selection. Pacific Grove, CA: Roy A. Squires and Clyde Beck. Verse. This volume was prepared while Smith was still living but he died before it could see print. It was published 'In memoriam'.

- 1971: Selected Poems. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, Nov 1971. This volume was delivered by the author to Arkham House in December 1949 but remained unpublished until 1971.

Night Shade Books

- The Collected Fantasies of Clark Ashton Smith 5-volume work

- Miscellaneous Writings. Originally announced as Tales of India and Irony (a collection of non-fantasy/science fiction/horror tales, planned to be available only to subscribers of above collection). Now commercially available.

- Red World of Polaris (complete tales of Captain Volmar)

Hippocampus Press

- The Complete Poetry and Translations of Clark Ashton Smith (3 vols)

- The Black Diamonds. A juvenile Oriental fantasy.

- The Last Oblivion: Best Fantastic Poems of Clark Ashton Smith

- The Sword of Zagan and Other Writings. Juvenile Oriental fantasy.

- The Shadow of the Unattained: Letters of George Sterling and Clark Ashton Smith

- The Freedom of Fantastic Things: Selected Criticism on Clark Ashton Smith

Arkham House

- Out of Space and Time

- Lost Worlds

- Genius Loci and Other Tales

- The Dark Chateau

- Spells and Philtres

- The Abominations of Yondo

- Tales of Science and Sorcery

- Poems in Prose

- Other Dimensions (o.o.p.)

- Selected Poems

- The Black Book of Clark Ashton Smith

- A Rendezvous in Averoigne

- Selected Letters of Clark Ashton Smith

Spearman (reprinted from Arkham House)

Panther (reprinted from Arkham House)

- Lost Worlds (published in 2 volumes, ISBN 0-586-03964-3, ISBN 0-586-04086-2)

- Genius Loci ISBN 0-586-03965-1

- The Abominations of Yondo ISBN 0-586-03956-2

- Other Dimensions (published in 2 volumes, ISBN 0-586-04350-0, ISBN 0-586-04351-9)

- Out of Space and Time (published in 2 volumes, ISBN 0-586-03966-X, ISBN 0-586-04110-9)

- Tales of Science and Sorcery ISBN 0-586-04352-7

Ballantine Adult Fantasy series

- Zothique 1970 ISBN 0-345-01938-5

- Hyperborea 1971 ISBN 0-345-02206-8

- Xiccarph 1972 ISBN 0-345-02501-6

- Poseidonis 1973 ISBN 0-345-03353-1

- Averoigne (reportedly compiled by series editor Lin Carter, but never released)

Wildside Press

- The Double Shadow

- The Maker of Gargoyles and Other Stories

- The White Sybil and Other Stories

Timescape Books

- The City of the Singing Flame 1981 ISBN 0-671-83415-0

- The Last Incantation 1982 ISBN 0-671-83543-2

- The Monster of the Prophecy 1983 ISBN 0-671-83544-0

HIH Art Studios

- Shadows Seen and Unseen: Poetry from the Shadows. San Jose, CA: Hih Art Studios, 2007. Edited by Raymond L. Johnson and Ardath W. Winterowd and signed by both editors. Limited to 540 copies. Hardcover in slipcase. Includes reproductions of poetry mansuscripts by Smith, and color plates of several Smith paintings.

Penguin Books

- The Dark Eidolon and Other Fantasies. Ed, S. T. Joshi. 2014.

Other

- Smith, Clark Ashton. Planets and Dimensions: Collected Essays. Edited by Charles K. Wolfe. Baltimore MD: Mirage Press, 1973.

- Emperor of Dreams. Ed, Stephen Jones. Gollancz, 2002. An omnibus edition in paperback of Smith's best tales.

- In the Line of the Grotesque and Monstrous. Introduction by D.S. Black. Berkeley: The Bancroft Library, 2004. Prints the text of three letters by Smith to Samuel Loveman. 50 copies only printed, in burnt orange wrappers. Printed on the Bancroft library's 1856 Albion handpress.

- The Black Abbot of Puthuum. Glendale, CA: The RAS Press, Oct 2007. Limited to 250 numbered copies.

- Roy A. Squires, bookman and letterpress printer, issued many limited edition pamphlets consisting of individual Smith poems and prose poems.

Scholars S.T. Joshi and David E. Schultz are preparing various volumes of Smith's letters to such of his individual correspondents as Donald Wandrei, [Robert H. Barlow]], and August Derleth.

Media adaptations and audio recordings

- Clark Ashton Smith: Live from Auburn: The Elder Tapes. In the late 1950s Smith recorded a number of his poems on the taperecorder of his friend Robert B. Elder. Elder chose the 11 poems at random from Smith's books The Dark Chateau and "Spells and Philtres". (Elder had first met Smith when reporting on his 1954 wedding to the former Carol Dorman for The Auburn Courier and they became friends when Smith praised Elder's novel Whom the Gods Destroy.) In 1995 Necronomicon Press released the audiocassette Clark Ashton Smith: Live from Auburn: The Elder Tapes, which includes an introduction by Elder and then Smith reading his poems. The recording was produced by Wayne Haigh. The cassette was accompanied by a booklet feasturing a c.1960 photo of Smith and reprints all 11 poems. Gahan Wilson provided the cover art for cassette and booklet. The recording has not been released on CD.

- "The Double Shadow" was filmed by Azathoth Productions on Super 8 film in 1975 with a script by Leigh Blackmore.[20]

- "The Return of the Sorcerer" was adapted for an episode of the television series Night Gallery, starring Vincent Price and Bill Bixby.

- "The Seed from the Sepulcher", "The Vaults of Yoh Vombis" and "The Return of the Sorcerer" were adapted as ten-page comics by Richard Corben, published in DenSaga 1, 2 and 3 respectively (Fantagor Press 1992–1993).

- "Mother of Toads" was adapted as segment one of the six-segment horror anthology film The Theatre Bizarre (2011).

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clark Ashton Smith. |

Notes

- ↑ Thomas, G. W. "A Reader's Guide to Sword & Sorcery S-V". Retrieved September 27, 2012.

- ↑ de Camp 1976, p. 206

- ↑ Eldritchdark.com

- ↑ de Camp 1976, p. 197-98

- ↑ Behrends 1990, p. 5

- ↑ de Camp 1976, p. 200

- ↑ Schultz & Connors 2003, p. xix

- ↑ Smith, Clark Ashton (1922). Ebony and Crystal: Poems in Verse and Prose. Auburn, California.

- ↑ Murray 1990

- ↑ de Camp 1976, p. 203

- ↑ Brian Stableford, "Clark Ashton Smith" in David Pringle (ed), St James Guide to Fantasy Writers, Detroit MI: St James Press, 1996, pp.529-30

- ↑ Steve Behrends. "The Song of the Necromancer: 'Loss' in Clark Ashton Smith's Fiction". Studies in Weird Fiction 1, No 1 (Summer 1986), 3–12.

- ↑ Haefele 2010, p.170

- ↑ Clark Ashton Smith at Find a Grave

- ↑ "Clark Ashton Smith (1893–1961) – Photos". Find a Grave. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ↑ Haefele 2010, p.172

- ↑ Harvey, Ryan (April 9, 2008). "The Fantasy Cycles of Clark Ashton Smith PART III: Tales of Zothique". Black Gate. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ↑ Many examples are reproduced in Dennis Rickard (1973). The Fantastic Art of Clark Ashton Smith. Baltimore: The Mirage Press.

- ↑ "Gallery of Art by Clark Ashton Smith". December 30, 2009. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ↑ Blackmore, Leigh. "Past Projects". Retrieved September 18, 2013.

There is mention here of Azathoth productions, a filmmaking group within the [Horror Fantasy Society]. This group produced the unfinished short film "The Double Shadow" (based on the Clark Ashton Smith story)...

References

- De Camp, L. Sprague (1976). "Sierran Shaman: Clark Ashton Smith". Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: the Makers of Heroic Fantasy. Arkham House. ISBN 0-87054-076-9.

- Herron, Don. "Collecting Clark Ashton Smith". Firsts (October 2000).

- Joshi, S. T. (2008). "Clark Ashton Smith: Beauty Is for the Few," chapter 2 in Emperors of Dreams: Some Notes on Weird Poetry. Sydney: P’rea Press. ISBN 978-0-9804625-3-1 (pbk) and ISBN 978-0-9804625-4-8 (hbk).

- Murray, Will. "The Clark Ashton Smythos" in Price, Robert M. (ed). The Horror of it All: Encrusted gems from the Crypt of Cthulhu. Mercer Island WA: Starmont House, 1990. ISBN 1-55742-122-6.

Further reading

- Behrends, Steve. Clark Ashton Smith. Starmont Reader's Guide 49. Mercer Island, WA: Starmont House, 1990.

- Cockcroft, Thomas G.L. The Tales of Clark Ashton Smith: A Bibliography. Lower Hutt, New Zealand: Cockcroft, Nov 1961 (500 copies). The first published bibliography on Smith; superseded by Donald Sidney-Fryer's Emperor of Dreams (1978) – see below.

- Connors, Scott. The Freedom of Fantastic Things: Selected Criticism on Clark Ashton Smith. NY: Hippocampus Press, 2006.

- de Camp, L. Sprague. "Sierra Shaman: Clark Ashton Smith," in Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers: The Makers of Heroic Fantasy. Sauk City,. WI: Arkham House, 1976, 211-12.

- Fait, Eleanor. "Auburn Artist-Poet Utilizes Native Rock in Sculptures.". Sacramento Union (21 Dec 1941), 4C.

- Haefele, John D. "Far from Time: Clark Ashton Smith, August Derleth, and Arkham House." Weird Fiction Review No 1 (Fall 2010), 154–189.

- Hilger, Ronald. One Hundred Years of Klarkash-Ton. Averon Press, 1996.

- Klarkash-Ton: The Journal of Smith Studies No 1 (June 1988), Cryptic Publications. Edited by Steve Behrends. This journal was continued under a new title but with the numbering continued from No 1, thus the first issue of The Dark Eidolon: The Journal of Smith Studies, (Necronomicon Press) is numbered "2" (it appeared June 1989). There were only 3 issues in total. No 3 appeared in Dec 2002.

- Lost Worlds: The Journal of Clark Ashton Smith Studies, Seele Brennt Publications. Edited by Smith's biographer Scott Connors and Ronald S. Hilger. Issued annually, five numbers 2003–2008.

- Morris, Harry O. (ed). Nyctalops magazine. Special Clark Ashton Smith issue, 96 pp. (1973)

- Schultz, David E. and Scott Connors (ed). Selected Letters of Clark Ashton Smith. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House, 2003.

- Schultz, David E and S.T. Joshi. The Shadow of the Unattained: The Letters of George Sterling and Clark Ashton Smith. NY: Hippocampus Press, 2005.

- Sidney-Fryer, Donald. Emperor of Dreams: A Clark Ashton Smith Bibliography. West Kingston, RI: Donald M. Grant Publishers, 1978. A substantial work of scholarship but now over thirty years out of date. A quantity of more recent bibliographical information can be found at the Bibliography section of the Eldritch Dark site online (see External Links).

- Sidney-Fryer, Donald. The Last of the Great Romantic Poets. Albuquerque NM: Silver Scarab Press, 1973.

- Sidney-Fryer, Donald. Clark Ashton Smith: The Sorcerer Departs. West Hills, CA: Tsathoggua Press, Jan 1997. Dole: Silver Key Press, 2007. Updated/revised version of his essay in the Special CAS Issue of Nyctalops (see above under Morris).

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Clark Ashton Smith |

- The Eldritch Dark – This website contains almost all of Clark Ashton Smith's written work, as well as a comprehensive selection of his art, biographies, a bibliography, a discussion board, readings, fiction tributes and more.

- Eldonejo ‘Mistera Sturno’ – A growing collection of authorized translations into Esperanto for free distribution as ebooks.

- Smith's poem "A Chant to Sirius" read by Leigh Blackmore

- Works by Clark Ashton Smith at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Clark Ashton Smith at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Clark Ashton Smith at Internet Archive

- Works by Clark Ashton Smith at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Clark Ashton Smith at Open Library

- Clark Ashton Smith at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Clark Ashton Smith: Poems – A collection of Clark Ashton Smith's early poetry.

- LibraryThing author profile

- Clark Ashton Smith essays – various critical essays on Smith, including discussion of his links with H. Rider Haggard, A.E. Housman, Huysmans and Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond