Boston Gazette

|

| |

| Type | Weekly newspaper |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1719 |

| Language | English |

| Ceased publication | 1798 |

| Headquarters |

Boston, Massachusetts |

The Boston Gazette (1719–1798) was a newspaper published in Boston, Massachusetts, in the British North American colonies. It began publication December 21, 1719 and appeared weekly. It should not be confused with the Boston gazette (1803–16).

The Boston Gazette (published by Benjamin Edes and John Gill) was probably the most influential newspaper ever in American history.[1][2]

The Boston News-Letter, the first successful newspaper in the Colonies had begun its long run in 1704. In 1741 the Boston Gazette incorporated the New-England Weekly Journal and became the Boston-Gazette, or New-England Weekly Journal. Contributors included: Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, Phyllis Wheatley.

Publishers, and men acting their behalf, included: (dates are approximate)[3]

- Benjamin Edes, Ben Franklin, James Franklin (1719)

- William Brooker (1719)

- Philip Musgrave (1720)

- Thomas Lewis (1725–26)

- Henry Marshall (1726–27)

- Bartholomew Green (1727–32)

- John Boydell (died December 11, 1739) (1732–36)

- Timothy Green (1736–41)

- Samuel Kneeland (1720–53)

- John Gill (1755–75) DAR Patriot # A044675

- Benjamin Edes (1755–94)

- Benjamin Edes, Jr. (1779–94)

- Peter Edes (1779 – c. 1784)

The paper's masthead vignette, produced by Paul Revere shows a seated Britannia with Liberty cap on staff, freeing a bird from a cage. Motto: "Containing the freshest Advices, Foreign and Domestic" This issue is often reprinted.[4]

"After the Revolution [the paper] lost its great contributors and its tone and policy were changed. It bitterly opposed the adoption of the constitution of the United States and the administration of Washington. The paper declined in power, interest and popular favor, till, after a long struggle, in 1798, it was discontinued for want of support."[5]

Hutchinson Letters leak

Benjamin Franklin acquired a packet of about twenty letters that had been written to Thomas Whately, an assistant to Prime Minister George Grenville.[6] Upon reading them, Franklin concluded that Massachusetts Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson and his colonial secretary (plus brother-in-law) Andrew Oliver, had mischaracterized the situation in the colonies, and thus misled Parliament. He felt that wider knowledge of these letters would then focus colonial anger away from Parliament and at those who had written the misleading letters.[7][8] Franklin sent the letters to Thomas Cushing, the speaker of the Massachusetts assembly, in December 1772.[7] He specifically wrote to Cushing that the letters should be seen only by a few people, and that he was not "at liberty to make the letters public."[9]

The letters arrived in Massachusetts in March 1773, and came into the hands of Samuel Adams, then serving as the clerk of the Massachusetts assembly.[10] By Franklin's instructions, only a select few people, including the Massachusetts Committee of Correspondence, were to see the letters.[11] Alarmed at what they read, Cushing wrote Franklin, asking if the restrictions on their circulation could be eased. In a response received by Cushing in early June, Franklin reiterated that they were not to be copied or published, but could be shown to anyone

A longtime opponent of Hutchinson's, Samuel Adams informed the assembly of the existence of the letters, after which it designated a committee to analyze them. Strategic leaks suggestive of their content made their way into the press and political discussions, causing Hutchinson much discomfort. The assembly eventually concluded, according to John Hancock, that in the letters Hutchinson sought to "overthrow the Constitution of this Government, and to introduce arbitrary Power into the Province", and called for the removal of Hutchinson and Oliver.[12] Hutchinson complained that Adams and the opposition were misrepresenting what he had written, and that nothing he had written in them on the subject of Parliamentary supremacy went beyond other statements he had made.[13] The letters were finally published in the Boston Gazette in mid-June 1773,[14] causing a political firestorm in Massachusetts and raising significant questions in England.[15]

American Revolution

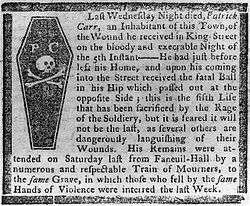

It essentially started the American Revolution. For years before the first shots were fired at Lexington Green, Samuel Adams, Joseph Warren, Josiah Quincy, James Otis, Edes and Gill were writing article after article in the Boston Gazette, rebelling against royal authority. Adams wrote so many articles, under so many pen names (at least 25), historians don't even know exactly how many he wrote. It was the Boston Gazette that hired Paul Revere to create his famous engraving of the Boston Massacre.[16][17]

The British officials hated the Boston Gazette. British officers placed the paper's name on a list of enemy institutions to be captured, and if possible, laid waste. Those trumpeters of sedition, Edes and Gill, were to be put out of business once and for all.[18][19]

The Sons of Liberty met at the Boston Gazette. It was there that they darkened their faces, disguising themselves as Mohawk Indians before setting out to dump British tea into Boston Harbor at the Boston Tea Party. Samuel Adams practically lived at the Boston Gazette.[20][21][22]

Varying Titles

- Boston gazette (Dec. 21, 1719-Oct. 19, 1741).

- Boston gazette, or, New England weekly journal (Oct. 20, 1741).

- Boston gazette, or, Weekly journal (Oct. 27, 1741-Dec. 26, 1752).

- Boston gazette, or, Weekly advertiser (Jan. 3, 1753-Apr. 1, 1755).

- Boston gazette, or, Country journal (Apr. 7, 1755-Apr. 5, 1756).

- Boston gazette, and The Country journal (Apr. 12, 1756-Dec. 30, 1793).

- Boston gazette, and Weekly republican journal (Jan. 6, 1794-Sept. 17, 1798).

In recent years, the Boston Gazette print shop of Edes & Gill has been recreated and is open to the public as a museum in Boston.

References

- ↑ Burns, Eric. Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism, pp 220-1, 136-7, Public Affairs, New York, New York, 2006. ISBN 978-1-58648-334-0.

- ↑ Copeland, David A. Debating the Issues in Colonial Newspapers: Primary Documents on Events of the Period, pp 3, 10, 195-7, 200, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30982-5.

- ↑ "Massachusetts - Eighteenth-Century American Newspapers in the Library of Congress (Serial and Government Publications Division)". Loc.gov. 2010-07-19. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ↑ "HistoryBuff.com". HistoryBuff.com. Archived from the original on 2017-07-23. Retrieved 2013-04-27.

- ↑ Isaiah Thomas. The History of Printing in America: With a Biography of Printers, and an Account of Newspapers. From the press of Isaiah Thomas, 1874; p.lx.

- ↑ Penegar, p. 27. Penegar notes that there are varying interpretations on how many letters constitute the set at issue.

- 1 2 Morgan, p. 187

- ↑ Bailyn, p. 236

- ↑ Wright, p. 225

- ↑ Alexander, p. 150

- ↑ Bailyn, p. 239

- ↑ Alexander, p. 151

- ↑ Alexander, p. 152

- ↑ Bailyn, p. 240

- ↑ Penegar, p. 29

- ↑ Burns, Eric. Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism, pp 141, 144, 145, 148, 152, 166-7, Public Affairs, New York, New York, 2006. ISBN 978-1-58648-334-0.

- ↑ Fischer, David Hackett. Paul Revere's Ride, pp 20-25, Oxford University Press, New York, New York and Oxford, England, 1994. ISBN 0-19-508847-6.

- ↑ Burns, Eric. Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism, pp 136-7, Public Affairs, New York, New York, 2006. ISBN 978-1-58648-334-0.

- ↑ Fischer, David Hackett. Paul Revere's Ride, pp 271-3, Oxford University Press, New York, New York and Oxford, England, 1994. ISBN 0-19-508847-6.

- ↑ Burns, Eric. Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism, pp 159-60, Public Affairs, New York, New York, 2006. ISBN 978-1-58648-334-0.

- ↑ Fischer, David Hackett. Paul Revere's Ride, pp 20-25, 302, Oxford University Press, New York, New York and Oxford, England, 1994. ISBN 0-19-508847-6.

- ↑ Copeland, David A. Debating the Issues in Colonial Newspapers: Primary Documents on Events of the Period, pp 216-7, Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, 2000. ISBN 0-313-30982-5.

Further reading

- Apfelbaum. Early American Newspapers and Their Printers.

- Mary Farwell Ayer, Albert Matthews. Check-list of Boston newspapers, 1704–1780. Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1907.

- TOLD IN ADS; Newspaper Notices a Source of History. Paul Revere Advertised Sale of Best Psalm Tune. First Umbrella Picture in Boston Gazette. Boston Daily Globe, Mar 29, 1914. p.SM15.

- Brigham. History and Bibliography of American Newspapers. 1968.

- Holmberg, Georgia McKee. "British-American Whig Political Rhetoric, 1765–1776: A Content Analysis of the London Gazette, London Chronicle, and Boston Gazette" (dissertation). University of Pittsburgh, 1979.

- Walt Nott. From "uncultivated Barbarian" to "poetical genius": the public presence of Phillis Wheatley. MELUS. Fall 1993. Vol.18,Iss.3;p. 21(12).

- Patricia Bradley. The Boston Gazette and slavery as revolutionary propaganda. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 22 Sep 1995. Vol.72,Iss.3;p. 581(16).

- Sandra Moore. The Boston Gazette and Country Journal: Voice of resistance and mouthpiece of the Revolution (dissertation). University of Houston, 2005.

External links

- http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/amendIIIs2.html (Issue for: October 17, 1768): Samuel Adams' essay on John Locke's statement "Where Law ends, Tyranny begins".

- http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch3s4.html (Issue for: February 27, 1769) contained Samuel Adams' essay on the right of revolution.

- http://www.bostonmassacre.net/gazette/ (Issue for: March 12, 1770): report on the Boston Massacre.

- http://earlyamerica.com/review/winter96/massacre/ (Issue for: March 12, 1770)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20060405205328/http://www.walkingboston.com/history/article.shtml (Issue for: April 10, 1775)

- http://www.masshist.org/revolution/doc-viewer.php?item_id=851&old=1&mode=nav (1776)

- http://dlib.nyu.edu/maassimages/maass/jpg/001162s.jpg (1777)

- http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/religion/vc006437.jpg (1780)

- http://bostongazette.org/ Boston Gazette print shop of Edes & Gill museum website