Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area

| Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area | |

|---|---|

| Thale Noi Waterfowl Reserve | |

|

IUCN category III (natural monument or feature) | |

|

Thale Noi | |

|

Thale Noi Locator Map | |

| Location | Phatthalung Province, Thailand |

| Nearest city | Phatthalung |

| Coordinates | 7°46′00″N 100°09′11″E / 7.76667°N 100.15306°ECoordinates: 7°46′00″N 100°09′11″E / 7.76667°N 100.15306°E |

| Area | 460 km2 (180 sq mi) |

| Established | 29 April 1975 Ramsar Site 13 May 1998 |

| Governing body | Royal Forestry Department |

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area (alternate spelling: Talae or Talay) is a protected fresh water wetland located in Phatthalung province, southern Thailand. Covering an area of 460 km², the wetlands are situated approximately 20 km inland from the east coast peninsula of the Gulf of Thailand and 115 km north of the Malaysian border in Satun province. Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area is one of the largest natural freshwater lakes in South East Asia.[1] It is the smallest, northernmost basin in the chain of lagoons that form Songkhla Lake, spreading across three provincial boundaries into Nakhon Si Thammarat, Phatthalung and Songkhla provinces and is home to the critically endangered Irrawaddy dolphin (Orcaella brevirostris).[2][3]

History

The Thai name ‘Thale Noi’ translates to ‘little sea’ in English language (thale = sea; noi = little). The wetlands were internationally recognised as a biodiversity hotspot in 1975 when the Department of National Parks, Wildlife & Flora, under the Ministry of National Resources and Environment [4] and in conjunction with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared it a Protected Area Category III (Natural Monuments), aimed at protecting particular natural features of a small area with high visitor value.[5] The wetlands’ valuable feature is its provision of suitable breeding habitats for tens of thousands of native and migratory bird species. Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area was the first official non-hunting wildlife area declared in Thailand.[6] Furthermore, the Kuan Ki Sian knoll, a 4.94 km² area within the non-hunting grounds was declared as a ‘Wetland of International Importance’ in 1998 by the Ramsar Convention [3] for its diversity of flora and fauna species, its value as a breeding haven for myriad bird species and for the presence of vulnerable and endangered species inhabiting the area.[7] The wetlands are presently governed by the Royal Forestry Department who work with local authorities and communities to manage the reserve.[8]

Climate

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area experiences tropical monsoonal weather with little variation in average temperatures throughout the year. There are distinct wet and dry seasons experienced on the southern east coast of Thailand with the rainy season running from October to March and dry season from April to September; November being the wettest month of the year and July being the driest.[9]

Ecosystem dynamics

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area is part of the greater Songkhla Lake Basin, the largest lagoon lake in Thailand, covering an area of over 8,000 km2 (3,100 sq mi) in its entirety.[10][11] There are over 38,000 people residing within the Thale Noi area with income predominantly sourced from fishing and sedge basketry production.[12] The lake joins with Thale Luang, a 473 km2 (183 sq mi) basin, via 3 channels – Khlong Naang Riam, Khlong Ban Klang and Khlong Yuan,[13] however sluice gates were installed in 1956 by the Royal Irrigation Department to prevent salt water intrusion [14] to create freshwater conditions conducive to rice production [13] (see Environmental Threats). Thale Luang adjoins Thale Sap (360 km2 or 140 sq mi) which connects to the southernmost lake, Thale Sap Songkhla (182 km2 or 70 sq mi) that opens into the Gulf of Thailand [3][11] through a 380 m wide strait.[15] Approximately 94% (422 km2 or 163 sq mi) of the reserve is terrestrial and 6% (28 km2 or 11 sq mi) is aquatic.[8] Thale Noi lake is approximately 5 km wide and 6 km long with an average depth of 1.2 m,[3] however water levels fluctuate significantly with changing seasonal conditions, dropping to around 80 cm in dry season and increasing to a depth of 3 m in some areas during the wet season.[13]

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area is a biologically diverse wetland with multiple habitat types supporting a vast array of flora and fauna species. Dense Melaleuca forests dominate the north and south [16][17] with extensive rice paddy fields to the east and remaining areas combine swamp marsh, grassland and sedge beds, with only a relatively small area of open water.[16][18]

| Melaleuca forests | 170 km2 | 66 sq mi |

| Rice Paddies | 153 km2 | 59 sq mi |

| Swamp/Sedge/Grassland | 109 km2 | 42 sq mi |

| Open water | 28 km2 | 11 sq mi |

Flora

Plant life ranges from Melaleuca swamp forests to floating aquatic macrophytes and microscopic phytoplankton. Records from the late 1990s show there were 72 species of flora within the protected area of Thale Noi,[19] however more recent studies [12] reveal dramatic reductions in plant populations with only 25 species remaining in the reserve. This loss of biodiversity is due to the heavy impact human populations have had on the area through the over-exploitation of natural resources and pollution into the lake (see Environmental Threats).[20]

The Weeping Paperbark (Melaleuca leucadendron) and the White Samet (Melaleuca cajuputi) species bordering both ends of the reserve represent the largest Melaleuca habitat in Thailand.[16][21] These flood tolerant trees provide protective breeding grounds throughout the year for common native waterbird species such as the Little Cormorant (Phalocrocorax niger) and Purple Heron (Ardea purpurea), as well as other common avian species with annual breeding cycles including the Little Egret (Egretta garzetta), the Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) and the Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis).[6] The thick foliage of the Melaleuca forests also provides night roosting areas for migratory bird species from April to July, such as the Black-headed Ibis (Threskiornis melanocephalus),[6] an IUCN Near Threatened species.[22]

Other water adapted plant species found in the area include common mangrove species (Rhizophora apiculate and Sonneratia caseolaris); the Nipa Palm (Nypa fruticans); Siamese Balsa (Alstonia spathulata) and the Shore Eugenia (Syzygium antisepticum) [16] which all contribute to ecosystem stability for maintaining soil composition, food sources, sanctuary and breeding grounds for both terrestrial and aquatic species.

Herbaceous macrophytes present in the reserve also provide important habitats for birds, otters and other wildlife [20] and include reeds (Phragmites spp.); sedges (Cyperus spp.), rushes (Scirpus spp.); Spike-rush (Eleocharis spp.); Grey Sedge (Lepironia articulata); Rice Grass (Paspalum scrobiculatum) and other grasses (Scleria spp.); Sacred Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera); White Lotus (Nymphaea lotus); Blue lotus (Nymphaea nouchali); Water Snowflake (Nymphoides indica); Asian Watermoss (Salvinia cucullata); Golden Bladderwort (Utricularia aurea); Hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum); Green Algae (Chara spp.) and myriad other Phytoplankton species.[16][23] Many macrophyte populations form dense floating patches on the lake surface providing refuge and habitat for both mobile and sessile organisms.[24]

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area hosts several orchid species that are protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) [12] due to historical over-exploitation for their aesthetic appeal, including Finlayson’s Cymbidium (Cymbidium finlaysonianum) and the Aloe-leafed Cymbidium (Cymbidium aloifolium) both found on limestone outcrops within the reserve.

Economically valuable plants

Over-exploitation of Lepironia articulata, or Grey Sedge, in the Thale Noi region has led to shortages in supply for local communities’ dependent on the plant as a primary source of income.[21] This species is intensely harvested by over 1,000 local families (over 70% of working women),[3] who use the stems for weaving into mats, baskets, bags and other handicraft items for sale.[16] The cultivation of Lepironia articulata in the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area does not require legal land tenure and little financial outlay,[16] making it an attractive method of earning income for poor families.

- Grey Sedge Lepironia articulata

Royal Lotus Nelumbo nucifera

Royal Lotus Nelumbo nucifera

Royal or Sacred lotus, Nelumbo nucifera, are harvested extensively for food, medicine and religious ceremonies.[25] Thai people use all parts of this species for myriad uses including the rhizomes, stems, leaves, petals, pods and seeds in cooking; the flowers and leaves for Buddhist rituals; and the leaves, pods, petioles, stamens and pollen for treating a variety of ailments such as sinusitis, diabetes and fever.[25] Similarly, leaves from the Pandanus plant, Pandanus amaryllifolius, found within the reserve are commonly used throughout Thailand for flavouring dishes and adding natural green colouring to drinks and sweets,[21] as well as being used as a traditional medicine for treating diabetes.[26]

Fauna

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area is internationally recognised for the valuable habitat, breeding grounds and refuge it provides to an extensive variety of indigenous and migratory bird species. Myriad other species of mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish and other aquatic species also inhabit the wetlands providing valuable ecosystem services to local communities and as part of the greater food web. Many species in the wetlands have been declared as Vulnerable, Endangered or Critically Endangered by the IUCN and are listed on their Red List of Threatened Species .

Amphibians

Current records indicate that populations of all amphibians within the protected area are not threatened, however this is likely due to lack of available data. Amphibian species present in the reserve are: Black-spectacled Toad (Bufo melanostictus); Pointed-tongued Floating Frog (Occidozyga lima); Common Green Frog (Hylarana erythrae); Chinese Bullfrog (Rana rugulosa); White-lipped Tree Frog (Polypedates leucomystax); Burmese Squat Frog (Calluella guttulata) and the Malaysian Narrowmouth Toad (Kaloula pulchra).[16]

Fish & Shellfish

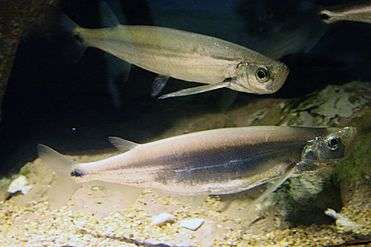

There are mixed reports to the number of fish species found in Thale Noi Lake with some ranging from 45 species [16] to other much lower figures of 26 species.[13] It is likely that many species have been lost from the wetlands due to habitat conversion, pollution and fragmentation resulting from agricultural expansion and industrialisation,[27] however more research is required to quantify the extent of loss. Siamese Fighting Fish (Betta splendens), once common in the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area are facing declining populations due to habitat destruction from land conversion, pollution and over-exploitation in the pet trade.[27] This species is commonly bred in Thailand for the purpose of betting on aggressive fighting male individuals and for their attractive colouring.[27] A secondary threat, as a consequence of the international trade of this species, is genetic erosion resulting from privately bred stock being released into wild areas.[28] This loss of genetic diversity increases the risk of local extinctions as populations become less adapted to survive in changing environments. It is reported that Prophagorus niuhofi, Walking Catfish, native to Thailand were previously found at Thale Noi,[16] however there is no recent literature available on the distribution of this species in the area. The Giant Sword Minnow (Macrochirichthys macrochirus) was once also found in Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area [29] however is now extirpated due to its sensitivities to pollution and gillnet fishing.[30]

Siamese Fighting Fish Betta splendens

Siamese Fighting Fish Betta splendens Sword Minnow Macrochirichthys macrochirus

Sword Minnow Macrochirichthys macrochirus

Other non-threatened aquatic species present in the wetlands include several economically valuable species - Snakehead (Channa spp.); Climbing Perch (Anabas testudineus); several catfish varieties; Grey Featherback (Notopterus notopterus), Swamp eel (Fluta alba), 2 freshwater prawn species (Macrobrachium lanchesteri, Macrobrachium rosenbergii) [16] and several crab species.

Reptiles

There are 25 recorded species of reptiles in the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area [16] with 4 species listed on the IUCN Red List as Vulnerable: the Southeast Asian Box Turtle (Cuora amboinensis); the Giant Asian Pond Turtle (Heosemys grandis); the Black Marsh Turtle (Siebenrockiella crassicollis) and the Southeast Asia Softshell Turtle (Amyda cartilaginea). Two species are currently listed as Endangered - the Yellow-headed Temple Turtle (Hieremys annandalii) and the Yellow-headed Tortoise (Indotestudo elongate), both of which are also listed on CITES due to trade exploitation.[31] Populations of these species have declined in Thailand due to extensive habitat loss from land conversion into rice fields, rubber tree plantations and shrimp farms. The Four-toed Terrapin (Batagur baska), a semi-aquatic species that lives in terrestrial and freshwater habitats,[32] was once found in the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area,[16] however is now Extinct in the Wild in Thailand,.[32]

River terrapin Batagur baska

River terrapin Batagur baska Asian Box Turtle Cuora amboinensis

Asian Box Turtle Cuora amboinensis

The 2 monitor species present in the wetlands, the Clouded Monitor (Varanus nebulosus) and the Asian Water Monitor (Varanus salvator) are both IUCN listed as Least Concern, however are protected in Thailand under the Wild Animal Reservation & Protection Act (WARPA).[33] All other reptile species are classified as Least Concern and include: Elephant Trunk Snake (Acrochordus javanicus); Reticulated Python (Python reticulatus); Banded Krait (Bungarus fasciatus); Monocled Cobra (Naja kaouthia); Striped Water Snake (Enhydris enhydris); Rice Paddy Snake (Enhydris plumbea); Puff-faced Water Snake (Homalopsis buccata) and several species of common terrestrial and water snakes, skinks and garden lizards.[16]

Mammals

There are 10 recorded species of mammals inhabiting the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area.[16] The Asian Small-Clawed Otter (Aonyx cinerea) [34] and the Smooth-coated Otter (Lutra perspicillata) are both on the IUCN Red List as Vulnerable species and Fishing Cat (Prionailurus viverrinus) is presently listed as Endangered.[35] Aonyx cinerea are considered ‘bioindicators’ of wetland ecosystems,[36] therefore declining populations within Thale Noi are concerning and indicates deteriorating ecological conditions that threatens the biodiversity of the entire ecosystem. The most significant threat to these species are the loss of habitat and population fragmentation due to land conversion into rice paddies and shrimp farms (Mukherjees et al. 2010). Over-fishing and trapping may also contribute to the declining Fishing Cat population in the region,[35] due to a reduction of food availability and increased risk of being killed by farmers protecting their stock or being sold in the illegal pet trade.[35] A recent study in 2013 [37] found that Fishing Cats in the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area were almost completely nocturnal, making recording individual numbers difficult to establish.

Asian Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinerea

Asian Small-clawed Otter Aonyx cinerea_3.jpg) Fishing Cat Prionailurus viverrinus

Fishing Cat Prionailurus viverrinus

Other mammal species found within the protected area are classified as Least Concern by the IUCN include the Crab-eating Macaque (Macaca fascicularis); Malayan Horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus malayanus); Common Palm Civit (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus); Jarvan Mongoose (Herpestes javanicus); Plantain Squirrel (Callosciurus notatus); Greater Bandicoot Rat (Bandicota indica); and the Polynesian Rat (Rattus exulans).[16] There are also over 4000 Water Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) farmed by approximately 280 families in the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area.[16] It is unknown what impact the numbers of buffalo have on the ecosystem, however many avian species use their grazing areas for feeding and breeding sites including heron, egrets, stilts and wader species.[16]

Birds

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area provides habitat and breeding grounds for over 180 native and migratory bird species that use the wetlands all year round or on their annual migratory journeys.[8] Research linking bird distributions to changing ecological conditions show that bird behaviour is an important biological indicator of change.[38] Populations of Cattle Egret (Bubulcus ibis), Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) and Black-headed Ibis (Threskiornis melanocephalus) species have shown to correlate with average temperatures, relative humidity and total rainfall.[6]

Globally threatened avian species listed on the IUCN Red List include: Baer’s Pochard (Aythya baeri), classified as Critically Endangered and may be extirpated from the Thale Noi area and from Thailand, however data is lacking on this species;[39] the Masked Finfoot (Heliopais personata) is Endangered; the Lessor Adjutant Stork (Leptoptilos javanicus) is Vulnerable, although it was once the most abundant species of stalk [29] but now may also be extirpated from Thailand due to no recent documented sightings;[40] and the Spot-billed Pelican (Pelecanus philippensis) is classified as Near Threatened. These species have all experienced rapid population declines due to land conversion for agriculture and industry causing habitat loss and environmental pollution that some species exhibit sensitivities to.[40] Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala), is classified as Near Threatened, have been recorded at the site in the past (Parr 1994), however it is now on the verge of extinction in Thailand.[41] Similarly, Black-headed Ibis (T. melanocephalus) populations are also in decline due to habitat destruction, degradation and fragmentation, currently listed by the IUCN as Near Threatened,[41] however large populations continue to breed in the wetlands between April to July, with over 20,000 individuals recorded in May 2002.[6]

Baer's Pochard Aythya baeri

Baer's Pochard Aythya baeri- tMasked Finfoot Heliopais personata

Non-threatened species, Purple Heron (Ardea purpurea) populations inhabit the reserve year round as one of only two breeding locations within Thailand and remain constant throughout the year.[6] Cormorants, waders, herons, egrets, crakes, bitterns, terns, grebe and kites are among other avian species found in the non-hunting area.[16]

Environmental Threats

The conversion of wetlands into agricultural and industrial lands is the most significant threat to biodiversity in Thailand.[25] Habitat destruction, fragmentation, pollution and overexploitation of the Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area has reduced populations of flora and fauna species with continuing risks of extirpation. Smaller populations result in declining genetic diversity of native species in the area, consequently losing their capacity to adapt to changing environmental conditions. Shrimp cultivation in the Songkhla Lake Basin alone rose from ~35 km2 in 1982 to ~78 km² in 2000 [42] changing the landscape from fertile wetland habitat to polluted and degraded water and soil resources over time. Clearing of mangrove forests in the protected area has also been reported with a reduction of over 87% land cover which leads to the destabilisation of the shoreline and significant loss of nursery areas for aquatic species.[42] Deforestation of both Melaleuca and mangrove forests bordering Thale Noi lake has increased soil erosion and runoff resulting in extensive sedimentation,[43] that has caused water levels to drop by ~10 cm every year increasing fish mortality.[3]

The construction of sluice gates at the northern part of Thale Luang in 1956 ceased the flow of saline water into Thale Noi lake,[14] creating a freshwater biome that had significant impacts on the ecosystem.[13] Reducing or eliminating connectivity between the larger lake system and Thale Noi lake affected the feeding and breeding cycles of fish and other aquatic fauna which consequently impacted the entire food web. Reports of increased weed infestation has also been documented as a result of limited salt-water intrusions that previously reduced populations.[13]

Eutrophication has been recorded in areas close to human settlements [1] as a consequence of pollutants entering the wetlands from households and industry. Unaware or unconcerned with the impacts of environmental degradation on the ecosystem, runoff from rubber and food production industries and surrounding pig, shrimp and crop farms [44] are additional sources of pollution contaminating the area. Toxic and unsustainable dying techniques used to colour sedge for basketry and handicraft has led to heavy metals including brass, lead, zinc, chromium and cadmium to enter the waterway, posing health risks to humans, animals and plant species in the vicinity.[12]

Management

Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area provides an array of valuable ecosystem services to local communities whose economy revolves almost explicitly around exploiting the lake’s resources.[20][45]

Freshwater wetlands are particularly vulnerable to human activities due to their disproportionate abundance of flora and fauna in both terrestrial and aquatic areas for refuge and habitat.[45] Education, training and enforcement of environmental protection laws needs to be more effective to ensure sustainable methods of cultivating and harvesting natural resources within the wetlands cause no further loss of biodiversity. Weak enforcement of regulations, lack of coordinated programming and inadequate data collection and record keeping have previously been identified as key issues of concern in the management of this ecosystem,[11] however it is unknown if these problems have been addressed in recent times. Immediate management concerns should focus on preserving biodiversity, improving water quality, preserving fishery resources and resolving social conflicts arising from resource usage in the area.[4][45] There are pockets of land within the protected area that remain in conflict between government authorities and locals due to missing land tenure documentation and non-adherence to environmental policies such as illegal land clearing, overfishing, not following designated boat routes and polluting the wetlands.[12]

The impact of climate change, particularly on wetlands, is steadily increasing, changing rainfall patterns, increasing storm frequency and intensity,[44] impacting all levels of biological and ecological systems. Dedicated management strategies are required to address these issues and the impact on Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area.

References

- 1 2 Coesel, P.F.M., [DOI: 10.1111/j.1756-1051.2000.tb00751."Desmids (Cholorphyta, Desmidiaceae) from Thale Noi (Thailand)"], Nordic Journal of Botany, 2000. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Ponnampalam et al., [DOI 10.1578/AM.39.4.2013.401 "Behavioral Observations of Irrawaddy Dolphins (Orcaella brevirostris) in Trat Province, Eastern Thailand"], Aquatic Mammals, 2013. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Iwasaki, S. & Shaw, R., [ISBN 978085724-163-4 "Integrated Lagoon Fisheries Management"], Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2010. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 Cookey, P., Darnswasdi, R. & Ratanchai, C., [doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2015.11.015 "Local People's Perceptions of Lake Basin Water Governance Performance in Thailand"], Ocean & Coastal Management, 2016. Retrieved 05-05-2016 .

- ↑ IUCN, "Protected Areas Category III", IUCN, 2014. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kaewdee,W., Thirakhupt, K. and Tunhikorn, S. , "Population of Waterbirds in the Breeding Colony at Khuan Khi Sian, Thailand’s First Ramsar Site", The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University, 2002. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Ramsar Convention Secretariat, "Ramsar Sites Criteria", Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2013. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Royal Thai Government, "Phatthalung Tourism Information", Royal Thai Government, 2016. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Thai Meteorological Department, "The Climate of Thailand", Thai Meteorological Department, 2014. Retrieved 19-05-2016.

- ↑ Chaiyakot, P. and Visuthismajarn, P., [www.cluteinstitute.com/ojs/index.php/IJMIS/article/download/6916/6991 "A Pattern of Rural Tourism In The Songkhla Lake Basin"], Thailand International Journal of Management & Information Systems, 2012. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Chufamanee, P. and Lonholdt, L., "Application of integrated environmental management through the preparation of an environmental action programme: Case study from the Songkhla Lake Basin in southern Thailand", Lakes & Reservoirs: Research and Management, 2001. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chiramanee, S., Churngchow, C. and Darnsawasdi, R.,"Political Ideology To Reduce Conflicts Of Interest In The Wetlands Of Thale Noi, Phatthalung Province, Thailand", Journal of Business Case Studies, 2012. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 King, V., ["Environmental Challenges in South East Asia"], Taylor & Francis Group, 1998.

- 1 2 Iwasaki, S. & Shaw, R., [doi:10.3850/S179392402009000106 "Human Security and Coping Brackish Environmental Hazards in Fishing Communities of Songkhla Lake, Thailand"], Asian Journal of Environment and Disaster Management, 2009. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Earth Snapshot, "Songkhla Lake: the Largest Natural Lake in Thailand - See more at: http://www.eosnap.com/image-of-the-day/songkhla-lake-the-largest-natural-lake-in-thailand-march-30th-2009/#sthash.SHvlQev7.dpuf", Chelys, 2009. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Parr, J.W.K., "A Socio-Economic and Tourism Assessment at Thale Noi Non-Hunting Area", Asia Foundation, 1994. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Storer, P.J., "A Study of the Waterfowl at Thale Noi", Natural History Bulletin Siam Society, 1977. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Birdlife International, "Important Bird and Biodiversity Areas - Thale Noi", Birdlife International, 2016. Retrieved 19-05-2016.

- ↑ Liangphonphan, S., "Forest inventory at Thale Noi Basin", AGRIS, 1999. Retrieved 14-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Pierce, G.J., Spray, C.J. and Stuart, E., "The Effect of Fishing on the Distribution and Behaviour of Waterbirds in the Kukut area of Lake Songkla, Southern Thailand", Biological Conservation, 1993. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Wunbua, J., Nakhapakorn, K. and Jirakajohnkool, S., "Change detection and identification of land potential for planting Krajood (Lepironia articulata ) in Thale Noi, Southern Thailand", Songklanakarin Journal of Science & Technology, 2012. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Birdlife International, "Threskiornis melanocephalus", IUCN Red List, 2012. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Ecological Research Division, ["Ecological Studies for Conservation of Shore Birds in Songkhla Lake"], Office of the National Environment Board of Thailand, 1981. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Meksuwan, P., Pholpunthin, P., Walsh, E.J., Segers, H. and Wallace, R., [Doi:10.1002/iroh.201301703 "Nestedness in sessile and periphytic rotifer communities: A meta-analysis"], International Review of Hydrobiology, 2014. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Laongsri, W., Trisonthi, C. and Balslev, H., "http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11273-008-9106-6", Wetlands Ecology Management, 2009. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Wakte, K.V., Nadaf, A.B., Ratnakar, J. and Jawali, N., [DOI 10.1007/s10722-009-9431-5 "Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. cultivated as a spice in coastal regions of India"], Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 2009. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Monvises, A., Nuangsaeng, B., Sriwattanarothai, N. and Panijpan, B., [doi:10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2009.35.008 "The Siamese fighting fish: Well-known generally but little-known scientifically"], Science Asia, 2009. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Vidthayanon, C., "Betta splendens", IUCN Red List, 2013. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 Humphrey, S. & Bain, J., ["Endangered Animals of Thailand"], The Sandhill Crane Press, 1990.

- ↑ Vidthayanon, C. & Allen, D.J., "Macrochirichthys macrochirus", IUCN Red List, 2013. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Asian Turtle Working Group, "Heosemys annandalii", IUCN Red List, 2000. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 Asian Turtle Working Group, "Batagur baska", IUCN Red List, 2000. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Lauprasert, K. & Thirakhupt, K., "Species Diversity, Distribution and Proposed Status of Monitor Lizards (Family Varanidae) in Southern Thailand", The Natural History Journal of Chulalongkorn University, 2001. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Wright, L., de Silva, P., Chan, B. & Reza Lubis, I., "Aonyx cinereus", IUCN Red List, 2015. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Mukherjee, S., Sanderson, J., Duckworth, W., Melisch, R., Khan, J., Wilting, A., Sunarto, S. & Howard, J.G., "Prionailurus viverrinus", IUCN Red List, 2010. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Rosli, M.K.A. et al., "A New Subspecies Identification and Population Study of the Asian Small-Clawed Otter (Aonyx cinereus) in Malay Peninsula and Southern Thailand Based on Fecal DNA Method", The Scientific World Journal, 2014. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Lynam, A. J., et. al., "Terrestrial Activity Patterns of Wild Cats from Camera Trapping", The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 2013. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Rittiboon, K. & Karntanut, W., "Distribution of Resident Birds in a Protected Tropical Habitat in South Thailand", International Society for Southeast Asian Agricultural Sciences, 2011. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- ↑ Birdlife International, "Aythya baeri", IUCN Red List, 2015. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 Birdlife International, "Leptoptilos javanicus", IUCN Red List, 2013. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 Birdlife International, "Mycteria leucocephala", IUCN Red List, 2012. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 Tanavud, C. Yongchalermchai, C., Bennui, A. and Kasetsart, O.D., "The Expansion of Inland Shrimp Farming and Its Environmental Impacts in Songkla Lake Basin", Journal of Natural Science, 2001. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- ↑ Reynolds, C. J., "Rural male leadership, religion and the environment in Thailand's mid-south, 1920s–1960s", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 2011. Retrieved 01-05-2016.

- 1 2 Cookey, P.E., Darnswasdi, R. and Ratanachai, C., [doi:10.3390/hydrology3010012 www.mdpi.com/journal/hydrology "A Conceptual Framework for Assessment of Governance Performance of Lake Basins: Towards Transformation to Adaptive and Integrative Governance"], Hydrology Journal, 2016. Retrieved 05-05-2016.

- 1 2 3 Dudgeon, D. et al., [doi:10.1017/S1464793105006950 "Freshwater biodiversity: importance, threats, status and conservation challenges"], Cambridge Philosophical Society, 2006. Retrieved 01-05-2016.