Royal tern

| Royal tern | |

|---|---|

| |

| Winter plumage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Thalasseus |

| Species: | T. maximus |

| Binomial name | |

| Thalasseus maximus (Boddaert, 1783) | |

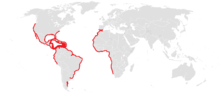

| |

| Range of T. maximus | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Sterna maxima | |

The royal tern (Thalasseus maximus) is a tern in the family Laridae. The genus name is from Ancient Greek Thalasseus, "fisherman", from thalassa, "sea". The specific maximus is Latin for '"greatest".[2]

This bird has two distinctive subspecies: T. m. maximus which lives on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of the North and South America, and the slightly smaller T. m. albididorsalis lives on the coast of West Africa. The royal tern has a red-orange bill and a black cap during the breeding season, but in the winter the cap becomes patchy. The royal tern is found in Europe, Africa, the Americas, and the Caribbean islands. The royal tern lives on the coast and is only found near salt water. They tend to feed near the shore, close to the beach or in backwater bays. The royal tern's conservation status is listed as least concern.

Taxonomy

The royal tern belongs to the class Aves and the order Charadriiformes. Charadriiformes are mainly seabirds of small to medium-large size. The royal tern is also in the family Sternidae because of its white plumage, black cap on its head, long bill, webbed feet, and bodies that are more streamlined than those of gulls.

The taxonomy of the royal tern has been debated, whether the correct scientific name was Thalasseus maximus or Sterna maxima. It is presently classified as Thalasseus maximus, which places it with five other seabirds from the tern family. The royal tern was originally placed in the genus Sterna; however, a 2005 study suggest that it is actually part of the genus Thalasseus.[3] Before 2017 the royal tern was divided into two subspecies: Thalasseus maximus maximus and Thalasseus maximus albididorsalis. T. m. maximus is found on the east coast of North America and is referred to as the "New World" species. T. m. albidorsalis, referred to as the "Old World" species, is found on the Atlantic coast of North America, the Caribbean Islands, the east coast of South America, and formerly on the west coast of Africa.[4]

It was suspected by wildlife conservationists in The Gambia that the West African birds were a separate species and analysis of DNA by scientists at the University of Aberdeen and the University of Montpellier have confirmed that the West African albididorsalis is a separate species. Feathers and other remains were collected from Mauritania and from islands off Tanji Bird Reserve, The Gambia and the DNA sequences shows the West African royal tern is closer to the lesser crested tern (Thalasseus bengalensis) then royal terns on the other side of the Atlantic.[5]

Description

This is a large tern, second only to Caspian tern but is unlikely to be confused with the carrot-billed giant, which has extensive dark under wing patches. The royal tern has an orange-red bill, pale grey upper parts and white under parts. Its legs are black. In winter, the black cap becomes patchy.[6] Juvenile royal terns are similar to non-breeding adults. Differences include juveniles having black splotched wings and a yellower bill. An adult royal tern has an average wingspan of 130 cm (51 in), for both sexes, but their wingspan can range from 125–135 cm (49–53 in). The royal tern's length ranges from 45–50 cm (18–20 in) and their average weight is anywhere from 350–450 g (12–16 oz).[7]

The calls of the royal tern are usually short, clear shrills. Some of the shrills sound like kree or tsirr; the royal tern also has a more plover like whistle that is longer, rolling and is more melodious.[8]

In various parts of its range, the royal tern could be confused with the elegant tern, lesser crested tern (the other orange-billed terns), and the greater crested tern. It is paler above than lesser crested tern and the yellow-billed great crested tern. The elegant tern has a longer more curved bill and shows more white on the forehead in winter.

Habitat and range

In the Americas, the royal terns on the east coast, during the breeding season (April to July), occur in the US north to Virginia, occasionally drifting north to Maryland. The southern end of their breeding range is Texas. The wintering range for on the east coast is from North Carolina south to Panama and the Guianas, also the Caribbean islands. On the western coast of the Americas, the royal tern spends the breeding season from the US state of California to Mexico, wintering from California south to Peru.[9]

In Africa, the royal tern is found along the west coast in the islands off the coast of Mauritania during the breeding season, but it is believed that there are undiscovered colonies on the west coast near or in Nigeria. The royal tern usually winters from Morocco south to Namibia. The royal tern is not usually found in Europe although it has been seen in Spain and Gibraltar. There have also been unconfirmed sightings farther north in Europe.[9]

American birds migrate south to Peru and Argentina for the winter to escape the cold weather. African breeders move both north and south from the breeding colonies.[6] African birds may reach as far north as Spain. This species has also wandered to Western Europe as a rare vagrant, these terns are probably from the American colonies.[9]

Behavior

Feeding

The royal tern typically feeds in small secluded bodies of water such as estuaries, mangroves, and lagoons. Also, but less frequently, the royal terns will hunt for fish in open water, typically within about 100 metres (110 yards) off the shore. The royal tern feeds in salt water and on very rare occasions in fresh water. When feeding they fly long distances from the colony to forage.[10] The royal tern feeds by diving into the water from heights near 30 feet (9.1 metres).[11] They usually feed alone or in groups of two or three, but on occasion they feed in large groups when hunting large schools of fish.[10]

The royal tern usually feeds on small fish such as anchovies, weakfish, and croakers. Fish are their main source of food but they also eat insects, shrimp, and crabs.[10][12] The royal tern feeds on small crabs, such as young blue crabs that swim near the surface of the water. When feeding on small crabs the royal tern does not use its normal plunge-dive technique, but instead uses short shallow dives so that they are concealed from their prey. The royal tern also uses this technique when hunting flying fish.[10]

Reproduction

_RWD1.jpg)

The royal tern nests on island beaches or isolated beaches with limited predators. It lays one or two eggs, usually in a scrape, an area on the ground where a tern has made a small hole to lay its eggs. In some cases, tern eggs are laid directly on the ground, not in a scrape. The eggs incubate from 25 to 30 days; after the eggs hatch the chicks remain in the scrape for about a week. About two weeks after hatching the chicks gather into groups called a crèche.[11] When the chicks are in the crèche, they are primarily fed by their parents who recognize their offspring by their voice and looks. While the chicks are in the crèche, they usually roam freely around the colony. In a large colony there can be thousands of chicks in the crèche.[4][13] When the chicks are a month old they fledge or start to fly. Royal terns mature around the age of 4 years, after which they build their own nests and reproduce.[11]

Like all white terns, it is fiercely defensive of its nest and young. The royal tern and the Cayenne tern nest and breed together in Argentina and Brazil.[14]

Threats

The royal tern has few predators when it is mature, but before the chicks hatch or while they are chicks the tern is threatened by humans, other animals, and the tides.[14] Humans threaten terns by fishing and by disrupting the tern nesting sites. Fishing nets can catch a tern while it is diving, making it unable to feed or it may cause it to drown if it is caught under water. Animals such as foxes, raccoon, and large gulls prey on tern chicks and tern eggs.

Tern nesting sites can also be affected by the tides; if a tern colony has nested too close to the high tide mark a spring tide would flood the nesting site and kill the chicks and make unhatched eggs infertile.[14][15]

Conservation

The royal tern is one of the species addressed in the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Water Birds (AEWA). The AEWA covers 255 species that depend on wetlands for part of their life. The AEWA covers birds from 64 countries in Africa and Eurasia.[16] There are little other conservation efforts because the royal tern's status is of least concern. The reason there is little concern for the extinction of the royal tern is that the species has not experienced a significant enough decrease in population to become threatened or endangered.[6]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Thalasseus maximus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 244, 383. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ Bridge, Eli S.; Jones, Andrew W.; Baker, Allan J. (2005). "A phylogenetic framework for the terns (Sternini) inferred from mtDNA sequences: implications for taxonomy and plumage evolution" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 35 (2): 459–469. PMID 15804415. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.12.010.

- 1 2 Buckley, P.A.; Buckley, Francine G. (2011). Poole, A., ed. "Royal tern". Introduction. The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.700. Retrieved 13 December 2011.

- ↑ "Royal revelations". BirdGuides. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Royal tern (Sterna maxima)". Planet of Birds. Retrieved 17 November 2011. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ "Royal Tern". All About Birds. Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

- ↑ Pough, Richard H. (1951). Audubon Water Bird Guide. Doubleday & Company, Inc. pp. 291–292. ISBN 0-385-06806-9.

- 1 2 3 Buckley, P.A.; Buckley, Francine G. (2011). Poole, A., ed. "Royal tern". Distribution. The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.700. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Buckley, P.A.; Buckley, Francine G. (2011). Poole, A., ed. "Royal tern". Food Habits. The Birds of North America Online. doi:10.2173/bna.700. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Clay, Roger (October 2006). "Royal tern". Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Favero, Marco; Silva R., M. Patricia; Mauco, Laura (1 June 2000). "Diet of royal (Thalasseus Maximus) and sandwich (T. Sandvicensis) terns during the Austral winter in the Buenos Aires Province, Argentina" (PDF). Ornitologia Neotropical. The Neotropical Ornithology Society. 11: 259–262. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Buckley, F.G.; Buckley, P.A. (3 April 2008). "The breeding ecology of royal terns Stena (Thalasseus) Maxima Maxima". Ibis. Wiley Online Library. 114 (3): 344–359. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1972.tb00832.x. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Yorioa, Pablo; Amorim Efe, Márcio (2007). "Population status of royal and cayenne terns breeding in Argentina and Brazil". Water Birds. The Waterbird Society. 34 (3). doi:10.1675/1524-4695-31.4.561. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ Erwin, R. Michael; Truitt, Barry R.; Jiménez, Jaime E. (Spring 2001). "Ground-Nesting Waterbirds and Mammalian Carnivores in the Virginia Barrier Island Region: Running out of Options" (PDF). Journal of Coastal Research. West Palm Beach, Florida: Coastal Education & Research Foundation, Inc. 17 (2): 292–296. ISSN 0749-0208. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ↑ "Agreement Birds". Bonn, Germany: AEWA. 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thalasseus maximus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Thalasseus maximus |

- "Royal Tern media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Royal tern photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Royal Tern species account at NeotropicalBirds (Cornell University)