Tetanus

| Tetanus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Muscle spasms (specifically opisthotonos) in a person with tetanus. Painting by Sir Charles Bell, 1809. | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Muscle spasms, fever, headache[1] |

| Usual onset | 3–21 days following exposure[1] |

| Duration | Months[1] |

| Causes | Clostridium tetani[1] |

| Risk factors | Break in the skin[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[1] |

| Prevention | Tetanus vaccine[1] |

| Treatment | Tetanus immune globulin, muscle relaxants, mechanical ventilation[1][3] |

| Frequency | 209,000 (2015)[4] |

| Deaths | 56,700 (2015)[5] |

Tetanus, also known as lockjaw, is an infection characterized by muscle spasms. In the most common type, the spasms begin in the jaw and then progress to the rest of the body. These spasms usually last a few minutes each time and occur frequently for three to four weeks.[1] Spasms may be so severe that bone fractures may occur.[6] Other symptoms may include fever, sweating, headache, trouble swallowing, high blood pressure, and a fast heart rate.[1][6] Onset of symptoms is typically three to twenty-one days following infection. It may take months to recover. About 10% of those infected die.[1]

Tetanus is caused by an infection with the bacterium Clostridium tetani,[1] which is commonly found in soil, saliva, dust, and manure.[2] The bacteria generally enter through a break in the skin such as a cut or puncture wound by a contaminated object.[2] They produce toxins that interfere with muscle contractions, resulting in the typical symptoms.[3] Diagnosis is based on the presenting signs and symptoms. The disease does not spread between people.[1]

Infection can be prevented by proper immunization with the tetanus vaccine. In those who have a significant wound and less than three doses of the vaccine both immunization and tetanus immune globulin are recommended. The wound should be cleaned and any dead tissue should be removed. In those who are infected tetanus immune globulin or, if it is not available, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is used.[1] Muscle relaxants may be used to control spasms. Mechanical ventilation may be required if a person's breathing is affected.[3]

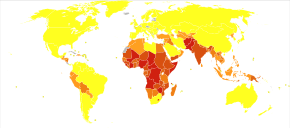

Tetanus occurs in all parts of the world but is most frequent in hot and wet climates where the soil contains a lot of organic matter.[1] In 2015 there were about 209,000 infections and about 59,000 deaths.[4][5] This is down from 356,000 deaths in 1990.[7] Description of the disease by Hippocrates exists from at least as far back as the 5th century BC. The cause of the disease was determined in 1884 by Antonio Carle and Giorgio Rattone at the University of Turin, with a vaccine being developed in 1924.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Tetanus often begins with mild spasms in the jaw muscles—also known as lockjaw or trismus. The spasms can also affect the facial muscles resulting in an appearance called risus sardonicus. Chest, neck, back, abdominal muscles, and buttocks may be affected. Back muscle spasms often cause arching, called opisthotonos. Sometimes the spasms affect muscles that help with breathing, which can lead to breathing problems.[8]

Prolonged muscular action causes sudden, powerful, and painful contractions of muscle groups, which is called "tetany". These episodes can cause fractures and muscle tears. Other symptoms include drooling, excessive sweating, fever, hand or foot spasms, irritability, difficulty swallowing, suffocation, heart attack, breathing problems, irregular heartbeat, and uncontrolled urination or defecation.

Even with treatment, about 10% of people who contract tetanus die.[8] The mortality rate is higher in unvaccinated people and people over 60 years of age.[8]

Incubation period

The incubation period of tetanus may be up to several months, but is usually about ten days.[9][10] In general, the farther the injury site is from the central nervous system, the longer the incubation period. The shorter the incubation period, the more severe the symptoms.[11] In neonatal tetanus, symptoms usually appear from 4 to 14 days after birth, averaging about 7 days. On the basis of clinical findings, four different forms of tetanus have been described.[8]

Generalized tetanus

Generalized tetanus is the most common type of tetanus, representing about 80% of cases. The generalized form usually presents with a descending pattern. The first sign is trismus, or lockjaw, and the facial spasms called risus sardonicus, followed by stiffness of the neck, difficulty in swallowing, and rigidity of pectoral and calf muscles. Other symptoms include elevated temperature, sweating, elevated blood pressure, and episodic rapid heart rate. Spasms may occur frequently and last for several minutes with the body shaped into a characteristic form called opisthotonos. Spasms continue for up to four weeks, and complete recovery may take months. Sympathetic overactivity (SOA) is common in severe tetanus and manifests as labile hypertension, tachycardia, dysrhythmia, peripheral vasculature constriction, profuse sweating, fever, increased carbon dioxide output, increased catecholamine excretion and late development of hypotension. Death can occur within four days.

Neonatal tetanus

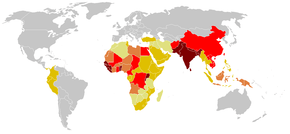

Neonatal tetanus is a form of generalized tetanus that occurs in newborns, usually those born to mothers who themselves have not been vaccinated. If the mother has been vaccinated against tetanus, the infants acquire passive immunity and are thus protected.[12] It usually occurs through infection of the unhealed umbilical stump, particularly when the stump is cut with a non-sterile instrument. As of 1998 neonatal tetanus was common in many developing countries and was responsible for about 14% (215,000) of all neonatal deaths.[13] In 2010 the worldwide death toll was 58,000 newborns. As the result of a public health campaign, the death toll from neonatal tetanus was reduced by 90% between 1990 and 2010, and by 2013 the disease had been largely eliminated from all but 25 countries.[14] Neonatal tetanus is rare in developed countries.

Local tetanus

Local tetanus is an uncommon form of the disease, in which patients have persistent contraction of muscles in the same anatomic area as the injury. The contractions may persist for many weeks before gradually subsiding. Local tetanus is generally milder; only about 1% of cases are fatal, but it may precede the onset of generalized tetanus.

Cephalic tetanus

Cephalic tetanus is the rarest form of the disease (0.9–3% of cases)[15] and is limited to muscles and nerves in the head.[16] It usually occurs after trauma to the head area, including skull fracture,[17] laceration,[17] eye injury,[16] dental extraction,[18] and otitis media,[19] but it has been observed from injuries to other parts of the body.[20] Paralysis of the facial nerve is most frequently implicated, which may cause lockjaw, facial palsy, or ptosis, but other cranial nerves can also be affected.[18][21] Cephalic tetanus may progress to a more generalized form of the disease.[15][21] Due to its rarity, clinicians may be unfamiliar with the clinical presentation and may not suspect tetanus as the illness.[16] Treatment can be complicated as symptoms may be concurrent with the initial injury that caused the infection.[17] Cephalic tetanus is more likely than other forms of tetanus to be fatal, with the progression to generalized tetanus carrying a 15–30% case fatality rate.[15][17][21]

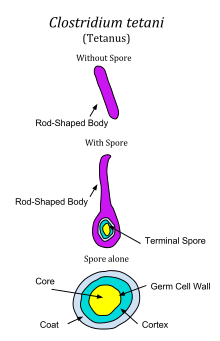

Cause

Tetanus is caused by the tetanus bacterium Clostridium tetani.[22] Tetanus is an international health problem, as C. tetani spores are ubiquitous. Spores can be introduced into the body through a puncture wound (penetrating trauma). Because C. tetani is an anaerobic bacterium, it and its endospores thrive in environments that lack oxygen. such as a puncture wound.

The disease occurs almost exclusively in persons inadequately immunized.[23] It is more common in hot, damp climates with soil rich in organic matter. Manure-treated soils may contain spores, as they are widely distributed in the intestines and feces of many animals such as horses, sheep, cattle, dogs, cats, rats, guinea pigs, and chickens.[8] In agricultural areas, a significant number of human adults may harbor the organism.

The spores can also be found on skin surfaces and in contaminated heroin.[8] Heroin users, particularly those that inject the drug subcutaneously, appear to be at high risk of contracting tetanus.[8] Rarely, tetanus can be contracted through surgical procedures, intramuscular injections, compound fractures, and dental infections.[24] The bite of a dog can transmit tetanus.[25]

Tetanus is often associated with rust, especially rusty nails. Although rust itself does not cause tetanus, objects that accumulate rust are often found outdoors or in places that harbour anaerobic bacteria. Additionally, the rough surface of rusty metal provides a habitat for C. tetani, while a nail affords a means to puncture skin and deliver endospores deep within the body at the site of the wound.[26] An endospore is a non-metabolizing survival structure that begins to metabolize and cause infection once in an adequate environment. Hence, stepping on a nail (rusty or not) may result in a tetanus infection, as the low-oxygen (anaerobic) environment is caused by the oxidization of the same object that causes a puncture wound, delivering endospores to a suitable environment for growth.[27]

Pathophysiology

Tetanus affects skeletal muscle, a type of striated muscle used in voluntary movement. The other type of striated muscle, cardiac, or heart muscle, cannot be tetanized because of its intrinsic electrical properties.

The tetanus toxin initially binds to peripheral nerve terminals. It is transported within the axon and across synaptic junctions until it reaches the central nervous system. There it becomes rapidly fixed to gangliosides at the presynaptic inhibitory motor nerve endings, and is taken up into the axon by endocytosis. The effect of the toxin is to block the release of inhibitory neurotransmitters glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) across the synaptic cleft, which is required to check the nervous impulse. If nervous impulses cannot be checked by normal inhibitory mechanisms, the generalized muscular spasms characteristic of tetanus are produced. The toxin appears to act by selective cleavage of a protein component of synaptic vesicles, synaptobrevin II, and this prevents the release of neurotransmitters by the cells.

Diagnosis

There are currently no blood tests for diagnosing tetanus. The diagnosis is based on the presentation of tetanus symptoms and does not depend upon isolation of the bacterium, which is recovered from the wound in only 30% of cases and can be isolated from patients without tetanus. Laboratory identification of C. tetani can be demonstrated only by production of tetanospasmin in mice.[8] Having recently experienced head trauma may indicate cephalic tetanus if no other diagnosis has been made.

The "spatula test" is a clinical test for tetanus that involves touching the posterior pharyngeal wall with a soft-tipped instrument and observing the effect. A positive test result is the involuntary contraction of the jaw (biting down on the "spatula") and a negative test result would normally be a gag reflex attempting to expel the foreign object. A short report in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene states that, in a patient research study, the spatula test had a high specificity (zero false-positive test results) and a high sensitivity (94% of infected patients produced a positive test).[28]

Prevention

Unlike many infectious diseases, recovery from naturally acquired tetanus does not usually result in immunity to tetanus. This is due to the extreme potency of the tetanospasmin toxin. Tetanospasmin will likely be lethal before it will provoke an immune response.

Tetanus can be prevented by vaccination with tetanus toxoid.[29] The CDC recommends that adults receive a booster vaccine every ten years,[30] and standard care practice in many places is to give the booster to any patient with a puncture wound who is uncertain of when he or she was last vaccinated, or if he or she has had fewer than three lifetime doses of the vaccine. The booster may not prevent a potentially fatal case of tetanus from the current wound, however, as it can take up to two weeks for tetanus antibodies to form.[31]

In children under the age of seven, the tetanus vaccine is often administered as a combined vaccine, DPT/DTaP vaccine, which also includes vaccines against diphtheria and pertussis. For adults and children over seven, the Td vaccine (tetanus and diphtheria) or Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis) is commonly used.[29]

The World Health Organization certifies countries as having eliminated maternal or neonatal tetanus. Certification requires at least two years of rates of less than 1 case per 1000 live births. In 1998 in Uganda, 3,433 tetanus cases were recorded in newborn babies; of these, 2,403 died. After a major public health effort, Uganda in 2011 was certified as having eliminated tetanus.[32]

Post-exposure prophylaxis

Tetanus toxoid can be given in case of a suspected exposure to tetanus. In such cases, it can be given with or without tetanus immunoglobulin (also called tetanus antibodies or tetanus antitoxin[33]). It can be given as intravenous therapy or by intramuscular injection.

The guidelines for such events in the United States for non-pregnant people 11 years and older are as follows:[34]

| Vaccination status | Clean, minor wounds | All other wounds |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown or less than 3 doses of tetanus toxoid containing vaccine | Tdap and recommend catch-up vaccination | Tdap and recommend catch-up vaccination Tetanus immunoglobulin |

| 3 or more doses of tetanus toxoid containing vaccine AND less than 5 years since last dose | No indication | No indication |

| 3 or more doses of tetanus toxoid containing vaccine AND 5–10 years since last dose | No indication | Tdap preferred (if not yet received) or Td |

| 3 or more doses of tetanus toxoid containing vaccine AND more than 10 years since last dose | Tdap preferred (if not yet received) or Td | Tdap preferred (if not yet received) or Td |

Treatment

Mild tetanus

Mild cases of tetanus can be treated with:[35]

- tetanus immunoglobulin (TIG),[1] also called tetanus antibodies or tetanus antitoxin.[33] It can be given as intravenous therapy or by intramuscular injection.

- metronidazole IV for 10 days

- diazepam oral or IV

Severe tetanus

Severe cases will require admission to intensive care. In addition to the measures listed above for mild tetanus:[35]

- Human tetanus immunoglobulin injected intrathecally (increases clinical improvement from 4% to 35%)

- Tracheotomy and mechanical ventilation for 3 to 4 weeks. Tracheotomy is recommended for securing the airway because the presence of an endotracheal tube is a stimulus for spasm

- Magnesium, as an intravenous (IV) infusion, to prevent muscle spasm

- Diazepam as a continuous IV infusion

- The autonomic effects of tetanus can be difficult to manage (alternating hyper- and hypotension hyperpyrexia/hypothermia) and may require IV labetalol, magnesium, clonidine, or nifedipine

Drugs such as diazepam or other muscle relaxants can be given to control the muscle spasms. In extreme cases it may be necessary to paralyze the patient with curare-like drugs and use a mechanical ventilator.

In order to survive a tetanus infection, the maintenance of an airway and proper nutrition are required. An intake of 3,500 to 4,000 calories and at least 150 g of protein per day is often given in liquid form through a tube directly into the stomach (percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy), or through a drip into a vein (parenteral nutrition). This high-caloric diet maintenance is required because of the increased metabolic strain brought on by the increased muscle activity. Full recovery takes 4 to 6 weeks because the body must regenerate destroyed nerve axon terminals.

Epidemiology

In 2013 it caused about 59,000 deaths – down from 356,000 in 1990.[7] Tetanus – in particular, the neonatal form – remains a significant public health problem in non-industrialized countries with 59,000 newborns worldwide dying in 2008 as a result of neonatal tetanus.[36][37] In the United States, from 2000 through 2007 an average of 31 cases were reported per year.[8] Nearly all of the cases in the United States occur in unimmunized individuals or individuals who have allowed their inoculations to lapse.[8]

History

Tetanus was well known to ancient people who recognized the relationship between wounds and fatal muscle spasms.[38] In 1884, Arthur Nicolaier isolated the strychnine-like toxin of tetanus from free-living, anaerobic soil bacteria. The etiology of the disease was further elucidated in 1884 by Antonio Carle and Giorgio Rattone, two pathologists of the University of Turin, who demonstrated the transmissibility of tetanus for the first time. They produced tetanus in rabbits by injecting pus from a patient with fatal tetanus into their sciatic nerves.[8]

In 1891, C. tetani was isolated from a human victim by Kitasato Shibasaburō, who later showed that the organism could produce disease when injected into animals, and that the toxin could be neutralized by specific antibodies. In 1897, Edmond Nocard showed that tetanus antitoxin induced passive immunity in humans, and could be used for prophylaxis and treatment. Tetanus toxoid vaccine was developed by P. Descombey in 1924, and was widely used to prevent tetanus induced by battle wounds during World War II.[8]

Etymology

The word tetanus comes from the Ancient Greek: τέτανος tetanos "taut", which is further from the Ancient Greek: τείνειν teinein "to stretch".[39]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Atkinson, William (May 2012). Tetanus Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12 ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 291–300. ISBN 9780983263135. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Tetanus Causes and Transmission". www.cdc.gov. January 9, 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Tetanus For Clinicians". cdc.gov. January 9, 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. PMID 27733282.

- 1 2 GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. PMID 27733281.

- 1 2 "Tetanus Symptoms and Complications". cdc.gov. January 9, 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. PMC 4340604

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

. PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Tetanus" (PDF). CDC Pink Book. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Vandelaer, J.; Birmingham, M.; Gasse, F.; Kurian, M.; Shaw, C.; Garnier, S. (July 28, 2003). "Tetanus in developing countries: an update on the Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination Initiative". Vaccine. 21 (24): 3442–5. PMID 12850356. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00347-5.

- ↑ Brauner, J. S.; Vieira, S. R.; Bleck, T. P. (July 2002). "Changes in severe accidental tetanus mortality in the ICU during two decades in Brazil". Intensive Care Medicine. 28 (7): 930–5. PMID 12122532. doi:10.1007/s00134-002-1332-4.

- ↑ Farrar, J. J.; Yen, L. M.; Cook, T.; Fairweather, N.; Binh, N.; Parry, J.; Parry, C. M. (September 2000). "Tetanus". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 69 (3): 292–301. PMC 1737078

. PMID 10945801. doi:10.1136/jnnp.69.3.292.

. PMID 10945801. doi:10.1136/jnnp.69.3.292. - ↑ "Tetanus and neonatal tetanus (NT)". WHO Western Pacific Region.

- ↑ "Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination by 2005" (PDF). UNICEF. November 2000. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ "Elimination of Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus". UNICEF. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 Doshi, A.; Warrell, C.; Dahdaleh, D.; Kullmann, D. (February 2014). "Just a graze? Cephalic tetanus presenting as a stroke mimic". Pract Neurol. 14 (1): 39–41. PMID 24052566. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2013-000541.

- 1 2 3 Del Pilar Morales, E.; Bertrán Pasarell, J.; Cardona Rodriguez, Z.; Almodovar Mercado, J. C.; Figueroa Navarro, A. (2014). "Cephalic tetanus following penetrating eye trauma: a case report". Bol Asoc Med P R. 106 (2): 25–9. PMID 25065047.

- 1 2 3 4 Adeleye, A. O.; Azeez, A. L. (October 2012). "Fatal tetanus complicating an untreated mild open head injury: a case-illustrated review of cephalic tetanus". Surg Infect (Larchmt). 13 (5): 317–20. PMID 23039234. doi:10.1089/sur.2011.023.

- 1 2 Ajayi, E.; Obimakinde, O. (July 2011). "Cephalic tetanus following tooth extraction in a Nigerian woman". J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2 (2): 201–2. PMC 3159367

. PMID 21897694. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.83597.

. PMID 21897694. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.83597. - ↑ Ugwa, G. I.; Okolugbo, N. E. (October–December 2012). "Otogenic tetanus: case series". West Afr J Med. 31 (4): 277–9. PMID 23468033.

- ↑ Kwon, J. C.; Park, Y.; Han, Z. A.; Song, J. E.; Park, H. S. (January 2013). "Trismus in cephalic tetanus from a foot injury". Korean J Intern Med. 28 (1): 121. PMC 3543954

. PMID 23346010. doi:10.3904/kjim.2013.28.1.121.

. PMID 23346010. doi:10.3904/kjim.2013.28.1.121. - 1 2 3 Seo, D. H.; Cho, D. K.; Kwon, H. C.; Kim, T. U. (February 2012). "A case of cephalic tetanus with unilateral ptosis and facial palsy". Ann Rehabil Med. 36 (1): 167–70. PMC 3309317

. PMID 22506253. doi:10.5535/arm.2012.36.1.167.

. PMID 22506253. doi:10.5535/arm.2012.36.1.167. - ↑ Mayy Clinic Staff. "Tetanus". The Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ Wells, C. L., Wilkins, T. D. (1996). "Clostridia: Sporeforming Anaerobic Bacilli". In Baron, S.; et al. Baron's Medical Microbiology. Univ of Texas Medical Branch. ISBN 0-9631172-1-1.

- ↑ "Tetanus | Causes and Transmission | Lockjaw | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2017-04-20.

- ↑ "Human Rabies Prevention, United States, Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2008. p. 2. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ Edmonds, Molly. "Causes of Tetanus". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Todar, Kenneth. "Tetanus". Lectures in Microbiology. University of Wisconsin, Madison - Dept. of Bacteriology.

- ↑ Apte NM, Karnad DR (October 1995). "Short Report: The Spatula Test: A Simple Bedside Test to Diagnose Tetanus". American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 53 (4): 386–7. PMID 7485691.

- 1 2 Hopkins, A.; Lahiri, T.; Salerno, R.; Heath, B. (1991). "Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis: recommendation for vaccine use and other preventive measures. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory committee (ACIP)". MMWR Recomm Rep. 40 (RR–10): 1–28. PMID 1865873. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0692.

- ↑ "CDC Features - Tetanus: Make Sure You and Your Child Are Fully Immunized". Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- ↑ Porter, J. D., Perkin, M. A., Corbel, M. J., Farrington, C. P., Watkins, J. T., Begg, N. T. (1992). "Lack of early antitoxin response to tetanus booster". Vaccine. 10 (5): 334–6. PMID 1574917. doi:10.1016/0264-410X(92)90373-R.

- ↑ "Uganda announces elimination of Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus". Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- 1 2 tetanus in Encyclopædia Britannica. Last Updated 7-17-2013

- ↑ , from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Page last updated August 12, 2013

- 1 2 World Health Organization. "Current recommendations for treatment of tetanus during humanitarian emergencies". Disease Control in Humanitarian Emergencies (English). WHO. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Maternal and Neonatal Tetanus Elimination Initiative" (PDF). Pampers UNICEF 2010 campaign: 2.

- ↑ Black, RE; Cousens, S; Johnson, HL; Lawn, JE; Rudan, I; Bassani, DG; Jha, P; Campbell, H; Walker, CF; Cibulskis, R; Eisele, T; Liu, L; Mathers, C; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF (Jun 5, 2010). "Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis.". Lancet. 375 (9730): 1969–87. PMID 20466419. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1.

- ↑ Pearce JM (1996). "Notes on tetanus (lockjaw)". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 60 (3): 332. PMC 1073859

. PMID 8609513. doi:10.1136/jnnp.60.3.332.

. PMID 8609513. doi:10.1136/jnnp.60.3.332. - ↑ tetanus. CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary - Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved October 01, 2012

External links

| Classification |

V · T · D |

|---|---|

| External resources |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tetanus. |

- Tetanus Information from Medline Plus

- Tetanus Surveillance -- United States, 1998-2000 (Data and Analysis)

- Video: Generalized tetanus in a 70-year-old woman (Neurology)

- Tetanus in dogs on YouTube