Abortion

| Abortion | |

|---|---|

|

Video explanation | |

| Synonyms | Induced miscarriage |

| Specialty | Obstetrics and gynecology |

| ICD-10-PCS | O04 |

| ICD-9-CM | 779.6 |

| MeSH | D000028 |

| MedlinePlus | 002912 |

Abortion is the ending of pregnancy by removing a fetus or embryo before it can survive outside the uterus.[note 1] An abortion that occurs spontaneously is also known as a miscarriage. An abortion may be caused purposely and is then called an induced abortion, or less frequently, "induced miscarriage". The word abortion is often used to mean only induced abortions. A similar procedure after the fetus could potentially survive outside the womb is known as a "late termination of pregnancy".[1]

When allowed by law, abortion in the developed world is one of the safest procedures in medicine.[2][3] Modern methods use medication or surgery for abortions.[4] The drug mifepristone in combination with prostaglandin appears to be as safe and effective as surgery during the first and second trimester of pregnancy.[4][5] Birth control, such as the pill or intrauterine devices, can be used immediately following abortion.[5] When performed legally and safely, induced abortions do not increase the risk of long-term mental or physical problems.[6] In contrast, unsafe abortions (those performed by unskilled individuals, with hazardous equipment, or in unsanitary facilities) cause 47,000 deaths and 5 million hospital admissions each year.[6][7] The World Health Organization recommends safe and legal abortions be available to all women.[8]

Around 56 million abortions are performed each year in the world,[9] with a little under half done unsafely.[10] Abortion rates changed little between 2003 and 2008,[10] before which they decreased for at least two decades as access to family planning and birth control increased.[11] As of 2008, 40% of the world's women had access to legal abortions without limits as to reason.[12] Countries that permit abortions have different limits on how late in pregnancy abortion is allowed.[12]

Since ancient times, abortions have been done using herbal medicines, sharp tools, with force, or through other traditional methods.[13] Abortion laws and cultural or religious views of abortions are different around the world. In some areas abortion is legal only in specific cases such as rape, problems with the fetus, poverty, risk to a woman's health, or incest.[14] In many places there is much debate over the moral, ethical, and legal issues of abortion.[15][16] Those who oppose abortion often maintain that an embryo or fetus is a human with a right to life and may compare abortion to murder.[17][18] Those who favor the legality of abortion often hold that a woman has a right to make decisions about her own body.[19]

Types

Induced

Approximately 205 million pregnancies occur each year worldwide. Over a third are unintended and about a fifth end in induced abortion.[10][20] Most abortions result from unintended pregnancies.[21][22] In the United Kingdom, 1 to 2% of abortions are done due to genetic problems in the fetus.[6] A pregnancy can be intentionally aborted in several ways. The manner selected often depends upon the gestational age of the embryo or fetus, which increases in size as the pregnancy progresses.[23][24] Specific procedures may also be selected due to legality, regional availability, and doctor or a women's personal preference.

Reasons for procuring induced abortions are typically characterized as either therapeutic or elective. An abortion is medically referred to as a therapeutic abortion when it is performed to save the life of the pregnant woman; prevent harm to the woman's physical or mental health; terminate a pregnancy where indications are that the child will have a significantly increased chance of premature morbidity or mortality or be otherwise disabled; or to selectively reduce the number of fetuses to lessen health risks associated with multiple pregnancy.[25][26] An abortion is referred to as an elective or voluntary abortion when it is performed at the request of the woman for non-medical reasons.[26] Confusion sometimes arises over the term "elective" because "elective surgery" generally refers to all scheduled surgery, whether medically necessary or not.[27]

Spontaneous

Spontaneous abortion, also known as miscarriage, is the unintentional expulsion of an embryo or fetus before the 24th week of gestation.[28] A pregnancy that ends before 37 weeks of gestation resulting in a live-born infant is known as a "premature birth" or a "preterm birth".[29] When a fetus dies in utero after viability, or during delivery, it is usually termed "stillborn".[30] Premature births and stillbirths are generally not considered to be miscarriages although usage of these terms can sometimes overlap.[31]

Only 30% to 50% of conceptions progress past the first trimester.[32] The vast majority of those that do not progress are lost before the woman is aware of the conception,[26] and many pregnancies are lost before medical practitioners can detect an embryo.[33] Between 15% and 30% of known pregnancies end in clinically apparent miscarriage, depending upon the age and health of the pregnant woman.[34] 80% of these spontaneous abortions happen in the first trimester.[35]

The most common cause of spontaneous abortion during the first trimester is chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo or fetus,[26][36] accounting for at least 50% of sampled early pregnancy losses.[37] Other causes include vascular disease (such as lupus), diabetes, other hormonal problems, infection, and abnormalities of the uterus.[36] Advancing maternal age and a women's history of previous spontaneous abortions are the two leading factors associated with a greater risk of spontaneous abortion.[37] A spontaneous abortion can also be caused by accidental trauma; intentional trauma or stress to cause miscarriage is considered induced abortion or feticide.[38]

Methods

Medical

Medical abortions are those induced by abortifacient pharmaceuticals. Medical abortion became an alternative method of abortion with the availability of prostaglandin analogs in the 1970s and the antiprogestogen mifepristone (also known as RU-486) in the 1980s.[4][5][39][40][41]

The most common early first-trimester medical abortion regimens use mifepristone in combination with a prostaglandin analog (misoprostol or gemeprost) up to 9 weeks gestational age, methotrexate in combination with a prostaglandin analog up to 7 weeks gestation, or a prostaglandin analog alone.[39] Mifepristone–misoprostol combination regimens work faster and are more effective at later gestational ages than methotrexate–misoprostol combination regimens, and combination regimens are more effective than misoprostol alone.[40] This regime is effective in the second trimester.[42] Medical abortion regiments involving mifepristone followed by misoprostol in the cheek between 24 and 48 hours later are effective when performed before 63 days' gestation.[43]

In very early abortions, up to 7 weeks gestation, medical abortion using a mifepristone–misoprostol combination regimen is considered to be more effective than surgical abortion (vacuum aspiration), especially when clinical practice does not include detailed inspection of aspirated tissue.[44] Early medical abortion regimens using mifepristone, followed 24–48 hours later by buccal or vaginal misoprostol are 98% effective up to 9 weeks gestational age.[45] If medical abortion fails, surgical abortion must be used to complete the procedure.[46]

Early medical abortions account for the majority of abortions before 9 weeks gestation in Britain,[47][48] France,[49] Switzerland,[50] and the Nordic countries.[51] In the United States, the percentage of early medical abortions is far lower.[52][53]

Medical abortion regimens using mifepristone in combination with a prostaglandin analog are the most common methods used for second-trimester abortions in Canada, most of Europe, China and India,[41] in contrast to the United States where 96% of second-trimester abortions are performed surgically by dilation and evacuation.[54]

Surgical

.svg.png)

1: Amniotic sac

2: Embryo

3: Uterine lining

4: Speculum

5: Vacurette

6: Attached to a suction pump

Up to 15 weeks' gestation, suction-aspiration or vacuum aspiration are the most common surgical methods of induced abortion.[55] Manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) consists of removing the fetus or embryo, placenta, and membranes by suction using a manual syringe, while electric vacuum aspiration (EVA) uses an electric pump. These techniques differ in the mechanism used to apply suction, in how early in pregnancy they can be used, and in whether cervical dilation is necessary.

MVA, also known as "mini-suction" and "menstrual extraction", can be used in very early pregnancy, and does not require cervical dilation. Dilation and curettage (D&C), the second most common method of surgical abortion, is a standard gynecological procedure performed for a variety of reasons, including examination of the uterine lining for possible malignancy, investigation of abnormal bleeding, and abortion. Curettage refers to cleaning the walls of the uterus with a curette. The World Health Organization recommends this procedure, also called sharp curettage, only when MVA is unavailable.[56]

From the 15th week of gestation until approximately the 26th, other techniques must be used. Dilation and evacuation (D&E) consists of opening the cervix of the uterus and emptying it using surgical instruments and suction. After the 16th week of gestation, abortions can also be induced by intact dilation and extraction (IDX) (also called intrauterine cranial decompression), which requires surgical decompression of the fetus's head before evacuation. IDX is sometimes called "partial-birth abortion", which has been federally banned in the United States.

In the third trimester of pregnancy, induced abortion may be performed surgically by intact dilation and extraction or by hysterotomy. Hysterotomy abortion is a procedure similar to a caesarean section and is performed under general anesthesia. It requires a smaller incision than a caesarean section and is used during later stages of pregnancy.[57]

First-trimester procedures can generally be performed using local anesthesia, while second-trimester methods may require deep sedation or general anesthesia.[53]

Labor induction abortion

In places lacking the necessary medical skill for dilation and extraction, or where preferred by practitioners, an abortion can be induced by first inducing labor and then inducing fetal demise if necessary.[58] This is sometimes called "induced miscarriage". This procedure may be performed from 13 weeks gestation to the third trimester. Although it is very uncommon in the United States, more than 80% of induced abortions throughout the second trimester are labor induced abortions in Sweden and other nearby countries.[59]

Only limited data are available comparing this method with dilation and extraction.[59] Unlike D&E, labor induced abortions after 18 weeks may be complicated by the occurrence of brief fetal survival, which may be legally characterized as live birth. For this reason, labor induced abortion is legally risky in the U.S.[59][60]

Other methods

Historically, a number of herbs reputed to possess abortifacient properties have been used in folk medicine: tansy, pennyroyal, black cohosh, and the now-extinct silphium.[61] The use of herbs in such a manner can cause serious—even lethal—side effects, such as multiple organ failure, and is not recommended by physicians.[62]

Abortion is sometimes attempted by causing trauma to the abdomen. The degree of force, if severe, can cause serious internal injuries without necessarily succeeding in inducing miscarriage.[63] In Southeast Asia, there is an ancient tradition of attempting abortion through forceful abdominal massage.[64] One of the bas reliefs decorating the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia depicts a demon performing such an abortion upon a woman who has been sent to the underworld.[64]

Reported methods of unsafe, self-induced abortion include misuse of misoprostol, and insertion of non-surgical implements such as knitting needles and clothes hangers into the uterus. These methods are rarely seen in developed countries where surgical abortion is legal and available.[65] All of these, and any other method to terminate pregnancy may be called "induced miscarriage".

Safety

The health risks of abortion depend principally upon whether the procedure is performed safely or unsafely. The World Health Organization defines unsafe abortions as those performed by unskilled individuals, with hazardous equipment, or in unsanitary facilities.[66] Legal abortions performed in the developed world are among the safest procedures in medicine.[2][67] In the US, the risk of maternal death from abortion is 0.7 per 100,000 procedures,[3] making abortion about 13 times safer for women than childbirth (8.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births).[68][69] The risk of abortion-related mortality increases with gestational age, but remains lower than that of childbirth through at least 21 weeks' gestation.[70][71][72] Outpatient abortion is as safe and effective from 64 to 70 days' gestation as it is from 57 to 63 days.[73] In the United States from 2000 to 2009, abortion had a lower mortality rate than plastic surgery.[74]

Vacuum aspiration in the first trimester is the safest method of surgical abortion, and can be performed in a primary care office, abortion clinic, or hospital. Complications are rare and can include uterine perforation, pelvic infection, and retained products of conception requiring a second procedure to evacuate.[75] Infections account for one-third of abortion-related deaths in the United States.[76] The rate of complications of vacuum aspiration abortion in the first trimester is similar regardless of whether the procedure is performed in a hospital, surgical center, or office.[77] Preventive antibiotics (such as doxycycline or metronidazole) are typically given before elective abortion,[78] as they are believed to substantially reduce the risk of postoperative uterine infection.[53][79] The rate of failed procedures does not appear to vary significantly depending on whether the abortion is performed by a doctor or a mid-level practitioner.[80] Complications after second-trimester abortion are similar to those after first-trimester abortion, and depend somewhat on the method chosen.

There is little difference in terms of safety and efficacy between medical abortion using a combined regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol and surgical abortion (vacuum aspiration) in early first trimester abortions up to 9 weeks gestation.[44] Medical abortion using the prostaglandin analog misoprostol alone is less effective and more painful than medical abortion using a combined regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol or surgical abortion.[81][82]

Some purported risks of abortion are promoted primarily by anti-abortion groups,[83][84] but lack scientific support.[83] For example, the question of a link between induced abortion and breast cancer has been investigated extensively. Major medical and scientific bodies (including the World Health Organization, National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, Royal College of OBGYN and American Congress of OBGYN) have concluded that abortion does not cause breast cancer.[85]

Mental health

There is no relationship between most induced abortions and mental-health problems[6][86] other than those expected for any unwanted pregnancy.[87] The American Psychological Association has concluded that a woman's first abortion is not a threat to mental health when carried out in the first trimester, with such women no more likely to have mental-health problems than those carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term; the mental-health outcome of a woman's second or greater abortion is less certain.[87][88] Although some studies show negative mental-health outcomes in women who choose abortions after the first trimester because of fetal abnormalities,[89] more rigorous research would be needed to show this conclusively.[90] Some proposed negative psychological effects of abortion have been referred to by anti-abortion advocates as a separate condition called "post-abortion syndrome", which is not recognized by medical or psychological professionals in the United States.[91]

Unsafe abortion

Women seeking to terminate their pregnancies sometimes resort to unsafe methods, particularly when access to legal abortion is restricted. They may attempt to self-abort or rely on another person who does not have proper medical training or access to proper facilities. This has a tendency to lead to severe complications, such as incomplete abortion, sepsis, hemorrhage, and damage to internal organs.[92]

Unsafe abortions are a major cause of injury and death among women worldwide. Although data are imprecise, it is estimated that approximately 20 million unsafe abortions are performed annually, with 97% taking place in developing countries.[2] Unsafe abortions are believed to result in millions of injuries.[2][93] Estimates of deaths vary according to methodology, and have ranged from 37,000 to 70,000 in the past decade;[2][7][94] deaths from unsafe abortion account for around 13% of all maternal deaths.[95] The World Health Organization believes that mortality has fallen since the 1990s.[96] To reduce the number of unsafe abortions, public health organizations have generally advocated emphasizing the legalization of abortion, training of medical personnel, and ensuring access to reproductive-health services.[97] However, the Dublin Declaration on Maternal Health, signed in 2012, notes that "the prohibition of abortion does not affect, in any way, the availability of optimal care to pregnant women".[98]

A major factor in whether abortions are performed safely or not is the legal standing of abortion. Countries with restrictive abortion laws have higher rates of unsafe abortion and similar overall abortion rates compared to those where abortion is legal and available.[7][10][97][99][100][101][102] For example, the 1996 legalization of abortion in South Africa had an immediate positive impact on the frequency of abortion-related complications,[103] with abortion-related deaths dropping by more than 90%.[104] Similar reductions in maternal mortality have been observed after other countries have liberalized their abortion laws, such as Romania and Nepal.[105] A 2011 study concluded that in the United States, some state-level anti-abortion laws are correlated with lower rates of abortion in that state.[106] The analysis, however, did not take into account travel to other states without such laws to obtain an abortion.[107] In addition, a lack of access to effective contraception contributes to unsafe abortion. It has been estimated that the incidence of unsafe abortion could be reduced by up to 75% (from 20 million to 5 million annually) if modern family planning and maternal health services were readily available globally.[108] Rates of such abortions may be difficult to measure because they can be reported variously as miscarriage, "induced miscarriage", "menstrual regulation", "mini-abortion", and "regulation of a delayed/suspended menstruation".[109][110]

Forty percent of the world's women are able to access therapeutic and elective abortions within gestational limits,[12] while an additional 35 percent have access to legal abortion if they meet certain physical, mental, or socioeconomic criteria.[14] While maternal mortality seldom results from safe abortions, unsafe abortions result in 70,000 deaths and 5 million disabilities per year.[7] Complications of unsafe abortion account for approximately an eighth of maternal mortalities worldwide,[111] though this varies by region.[112] Secondary infertility caused by an unsafe abortion affects an estimated 24 million women.[100] The rate of unsafe abortions has increased from 44% to 49% between 1995 and 2008.[10] Health education, access to family planning, and improvements in health care during and after abortion have been proposed to address this phenomenon.[113]

Live birth

Although it is very uncommon, women undergoing surgical abortion after 18 weeks gestation sometimes give birth to a fetus that may survive briefly.[114][115][116] Longer term survival is possible after 22 weeks.[117]

If medical staff observe signs of life, they may be required to provide care: emergency medical care if the child has a good chance of survival and palliative care if not.[118][119][120] Induced fetal demise before termination of pregnancy after 20–21 weeks gestation is recommended to avoid this.[121][122][123][124][125]

Death following live birth which is caused by abortion is given the ICD-10 underlying cause description code of P96.4; data are identified as either fetus or newborn. Between 1999 and 2013, in the U.S., the CDC recorded 531 such deaths for newborns,[126] approximately 4 per 100,000 abortions.[127]

Incidence

There are two commonly used methods of measuring the incidence of abortion:

- Abortion rate – number of abortions per 1000 women between 15 and 44 years of age

- Abortion percentage – number of abortions out of 100 known pregnancies (pregnancies include live births, abortions and miscarriages)

In many places, where abortion is illegal or carries a heavy social stigma, medical reporting of abortion is not reliable.[99] For this reason, estimates of the incidence of abortion must be made without determining certainty related to standard error.[10]

The number of abortions performed worldwide seems to have remained stable in recent years, with 41.6 million having been performed in 2003 and 43.8 million having been performed in 2008.[10] The abortion rate worldwide was 28 per 1000 women, though it was 24 per 1000 women for developed countries and 29 per 1000 women for developing countries.[10] The same 2012 study indicated that in 2008, the estimated abortion percentage of known pregnancies was at 21% worldwide, with 26% in developed countries and 20% in developing countries.[10]

On average, the incidence of abortion is similar in countries with restrictive abortion laws and those with more liberal access to abortion. However, restrictive abortion laws are associated with increases in the percentage of abortions which are performed unsafely.[12][128][129] The unsafe abortion rate in developing countries is partly attributable to lack of access to modern contraceptives; according to the Guttmacher Institute, providing access to contraceptives would result in about 14.5 million fewer unsafe abortions and 38,000 fewer deaths from unsafe abortion annually worldwide.[130]

The rate of legal, induced abortion varies extensively worldwide. According to the report of employees of Guttmacher Institute it ranged from 7 per 1000 women (Germany and Switzerland) to 30 per 1000 women (Estonia) in countries with complete statistics in 2008. The proportion of pregnancies that ended in induced abortion ranged from about 10% (Israel, the Netherlands and Switzerland) to 30% (Estonia) in the same group, though it might be as high as 36% in Hungary and Romania, whose statistics were deemed incomplete.[131][132]

The abortion rate may also be expressed as the average number of abortions a woman has during her reproductive years; this is referred to as total abortion rate (TAR).

Gestational age and method

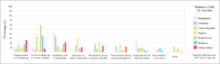

Abortion in the United States by gestational age, 2004. (right)

Abortion rates also vary depending on the stage of pregnancy and the method practiced. In 2003, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 26% of abortions in the United States were known to have been obtained at less than 6 weeks' gestation, 18% at 7 weeks, 15% at 8 weeks, 18% at 9 through 10 weeks, 9.7% at 11 through 12 weeks, 6.2% at 13 through 15 weeks, 4.1% at 16 through 20 weeks and 1.4% at more than 21 weeks. 90.9% of these were classified as having been done by "curettage" (suction-aspiration, dilation and curettage, dilation and evacuation), 7.7% by "medical" means (mifepristone), 0.4% by "intrauterine instillation" (saline or prostaglandin), and 1.0% by "other" (including hysterotomy and hysterectomy).[133] According to the CDC, due to data collection difficulties the data must be viewed as tentative and some fetal deaths reported beyond 20 weeks may be natural deaths erroneously classified as abortions if the removal of the dead fetus is accomplished by the same procedure as an induced abortion.[134]

The Guttmacher Institute estimated there were 2,200 intact dilation and extraction procedures in the US during 2000; this accounts for 0.17% of the total number of abortions performed that year.[135] Similarly, in England and Wales in 2006, 89% of terminations occurred at or under 12 weeks, 9% between 13 and 19 weeks, and 1.5% at or over 20 weeks. 64% of those reported were by vacuum aspiration, 6% by D&E, and 30% were medical.[136] There are more second trimester abortions in developing countries such as China, India and Vietnam than in developed countries.[137]

Motivation

Personal

The reasons why women have abortions are diverse and vary across the world.[134][138]

Some of the most common reasons are to postpone childbearing to a more suitable time or to focus energies and resources on existing children. Others include being unable to afford a child either in terms of the direct costs of raising a child or the loss of income while caring for the child, lack of support from the father, inability to afford additional children, desire to provide schooling for existing children, disruption of one's own education, relationship problems with their partner, a perception of being too young to have a child, unemployment, and not being willing to raise a child conceived as a result of rape or incest, among others.[138][139]

Societal

Some abortions are undergone as the result of societal pressures. These might include the preference for children of a specific sex or race,[140] disapproval of single or early motherhood, stigmatization of people with disabilities, insufficient economic support for families, lack of access to or rejection of contraceptive methods, or efforts toward population control (such as China's one-child policy). These factors can sometimes result in compulsory abortion or sex-selective abortion.[141]

An American study in 2002 concluded that about half of women having abortions were using a form of contraception at the time of becoming pregnant. Inconsistent use was reported by half of those using condoms and three-quarters of those using the birth-control pill; 42% of those using condoms reported failure through slipping or breakage.[142] The Guttmacher Institute estimated that "most abortions in the United States are obtained by minority women" because minority women "have much higher rates of unintended pregnancy."[143]

Maternal and fetal health

An additional factor is risk to maternal or fetal health, which was cited as the primary reason for abortion in over a third of cases in some countries and as a significant factor in only a single-digit percentage of abortions in other countries.[134][138]

In the U.S., the Supreme Court decisions in Roe vs Wade and Doe vs Bolton: "ruled that the state's interest in the life of the fetus became compelling only at the point of viability, defined as the point at which the fetus can survive independently of its mother. Even after the point of viability, the state cannot favor the life of the fetus over the life or health of the pregnant woman. Under the right of privacy, physicians must be free to use their "medical judgment for the preservation of the life or health of the mother." On the same day that the Court decided Roe, it also decided Doe v. Bolton, in which the Court defined health very broadly: "The medical judgment may be exercised in the light of all factors—physical, emotional, psychological, familial, and the woman's age—relevant to the well-being of the patient. All these factors may relate to health. This allows the attending physician the room he needs to make his best medical judgment."[144]:1200–1201

Public opinion shifted in America following television personality Sherri Finkbine's discovery during her fifth month of pregnancy that she had been exposed to thalidomide, unable to abort in the United States she traveled to Sweden. From 1962-65 there was an outbreak of German measles that left 15,000 babies with severe birth defects. In 1967, the American Medical Association publicly supported liberalization of abortion laws. A National Opinion Research Center poll in 1965 showed 73% supported abortion when the mothers life was at risk, 57% when birth defects were present and 59% for pregnancies resulting from rape or incest.[145]

Cancer

The rate of cancer during pregnancy is 0.02–1%, and in many cases, cancer of the mother leads to consideration of abortion to protect the life of the mother, or in response to the potential damage that may occur to the fetus during treatment. This is particularly true for cervical cancer, the most common type which occurs in 1 of every 2,000–13,000 pregnancies, for which initiation of treatment "cannot co-exist with preservation of fetal life (unless neoadjuvant chemotherapy is chosen)". Very early stage cervical cancers (I and IIa) may be treated by radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection, radiation therapy, or both, while later stages are treated by radiotherapy. Chemotherapy may be used simultaneously. Treatment of breast cancer during pregnancy also involves fetal considerations, because lumpectomy is discouraged in favor of modified radical mastectomy unless late-term pregnancy allows follow-up radiation therapy to be administered after the birth.[146]

Exposure to a single chemotherapy drug is estimated to cause a 7.5–17% risk of teratogenic effects on the fetus, with higher risks for multiple drug treatments. Treatment with more than 40 Gy of radiation usually causes spontaneous abortion. Exposure to much lower doses during the first trimester, especially 8 to 15 weeks of development, can cause intellectual disability or microcephaly, and exposure at this or subsequent stages can cause reduced intrauterine growth and birth weight. Exposures above 0.005–0.025 Gy cause a dose-dependent reduction in IQ.[146] It is possible to greatly reduce exposure to radiation with abdominal shielding, depending on how far the area to be irradiated is from the fetus.[147][148]

The process of birth itself may also put the mother at risk. "Vaginal delivery may result in dissemination of neoplastic cells into lymphovascular channels, haemorrhage, cervical laceration and implantation of malignant cells in the episiotomy site, while abdominal delivery may delay the initiation of non-surgical treatment."[149]

History and religion

Since ancient times abortions have been done using herbal medicines, sharp tools, with force, or through other traditional methods.[13] Induced abortion has long history, and can be traced back to civilizations as varied as China under Shennong (c. 2700 BCE), Ancient Egypt with its Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE), and the Roman Empire in the time of Juvenal (c. 200 CE).[13] There is evidence to suggest that pregnancies were terminated through a number of methods, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques. One of the earliest known artistic representations of abortion is in a bas relief at Angkor Wat (c. 1150). Found in a series of friezes that represent judgment after death in Hindu and Buddhist culture, it depicts the technique of abdominal abortion.[64]

Some medical scholars and abortion opponents have suggested that the Hippocratic Oath forbade Ancient Greek physicians from performing abortions;[13] other scholars disagree with this interpretation,[13] and state the medical texts of Hippocratic Corpus contain descriptions of abortive techniques right alongside the Oath.[151] The physician Scribonius Largus wrote in 43 CE that the Hippocratic Oath prohibits abortion, as did Soranus, although apparently not all doctors adhered to it strictly at the time. According to Soranus' 1st or 2nd century CE work Gynaecology, one party of medical practitioners banished all abortives as required by the Hippocratic Oath; the other party—to which he belonged—was willing to prescribe abortions, but only for the sake of the mother's health.[152][153]

Aristotle, in his treatise on government Politics (350 BCE), condemns infanticide as a means of population control. He preferred abortion in such cases, with the restriction[154] "[that it] must be practised on it before it has developed sensation and life; for the line between lawful and unlawful abortion will be marked by the fact of having sensation and being alive."[155] In Christianity, Pope Sixtus V (1585–90) was the first Pope to declare that abortion is homicide regardless of the stage of pregnancy;[156] the Catholic Church had previously been divided on whether it believed that abortion was murder, and did not begin vigorously opposing abortion until the 19th century.[13] Islamic tradition has traditionally permitted abortion until a point in time when Muslims believe the soul enters the fetus,[13] considered by various theologians to be at conception, 40 days after conception, 120 days after conception, or quickening.[157] However, abortion is largely heavily restricted or forbidden in areas of high Islamic faith such as the Middle East and North Africa.[158]

In Europe and North America, abortion techniques advanced starting in the 17th century. However, conservatism by most physicians with regards to sexual matters prevented the wide expansion of safe abortion techniques.[13] Other medical practitioners in addition to some physicians advertised their services, and they were not widely regulated until the 19th century, when the practice (sometimes called restellism)[159] was banned in both the United States and the United Kingdom.[13] Church groups as well as physicians were highly influential in anti-abortion movements.[13] In the US, abortion was more dangerous than childbirth until about 1930 when incremental improvements in abortion procedures relative to childbirth made abortion safer.[note 2] Soviet Russia (1919), Iceland (1935) and Sweden (1938) were among the first countries to legalize certain or all forms of abortion.[160] In 1935 Nazi Germany, a law was passed permitting abortions for those deemed "hereditarily ill", while women considered of German stock were specifically prohibited from having abortions.[161] Beginning in the second half of the twentieth century, abortion was legalized in a greater number of countries.[13] A bill passed by the state legislature of New York legalizing abortion was signed by Governor Nelson Rockefeller in April 1970.[162]

Society and culture

Abortion debate

Induced abortion has long been the source of considerable debate. Ethical, moral, philosophical, biological, religious and legal issues surrounding abortion are related to value systems. Opinions of abortion may be about fetal rights, governmental authority, and women's rights.

In both public and private debate, arguments presented in favor of or against abortion access focus on either the moral permissibility of an induced abortion, or justification of laws permitting or restricting abortion.[163] The World Medical Association Declaration on Therapeutic Abortion notes that "circumstances bringing the interests of a mother into conflict with the interests of her unborn child create a dilemma and raise the question as to whether or not the pregnancy should be deliberately terminated".[164] Abortion debates, especially pertaining to abortion laws, are often spearheaded by groups advocating one of these two positions. Anti-abortion groups who favor greater legal restrictions on abortion, including complete prohibition, most often describe themselves as "pro-life" while abortion rights groups who are against such legal restrictions describe themselves as "pro-choice".[165] Generally, the former position argues that a human fetus is a human person with a right to live, making abortion morally the same as murder. The latter position argues that a woman has certain reproductive rights, especially the choice whether or not to carry a pregnancy to term.

Modern abortion law

International status of abortion law

UN 2013 report on abortion law.[166]

Current laws pertaining to abortion are diverse. Religious, moral, and cultural sensibilities continue to influence abortion laws throughout the world. The right to life, the right to liberty, the right to security of person, and the right to reproductive health are major issues of human rights that are sometimes used as justification for the existence or absence of laws controlling abortion.

In jurisdictions where abortion is legal, certain requirements must often be met before a woman may obtain a safe, legal abortion (an abortion performed without the woman's consent is considered feticide). These requirements usually depend on the age of the fetus, often using a trimester-based system to regulate the window of legality, or as in the U.S., on a doctor's evaluation of the fetus' viability. Some jurisdictions require a waiting period before the procedure, prescribe the distribution of information on fetal development, or require that parents be contacted if their minor daughter requests an abortion.[168] Other jurisdictions may require that a woman obtain the consent of the fetus' father before aborting the fetus, that abortion providers inform women of health risks of the procedure—sometimes including "risks" not supported by the medical literature—and that multiple medical authorities certify that the abortion is either medically or socially necessary. Many restrictions are waived in emergency situations. China, which has ended their[169] one-child policy, and now has a two child policy.[170][171] has at times incorporated mandatory abortions as part of their population control strategy.[172]

Other jurisdictions ban abortion almost entirely. Many, but not all, of these allow legal abortions in a variety of circumstances. These circumstances vary based on jurisdiction, but may include whether the pregnancy is a result of rape or incest, the fetus' development is impaired, the woman's physical or mental well-being is endangered, or socioeconomic considerations make childbirth a hardship.[14] In countries where abortion is banned entirely, such as Nicaragua, medical authorities have recorded rises in maternal death directly and indirectly due to pregnancy as well as deaths due to doctors' fears of prosecution if they treat other gynecological emergencies.[173][174] Some countries, such as Bangladesh, that nominally ban abortion, may also support clinics that perform abortions under the guise of menstrual hygiene.[175] This is also a terminology in traditional medicine.[176] In places where abortion is illegal or carries heavy social stigma, pregnant women may engage in medical tourism and travel to countries where they can terminate their pregnancies.[177] Women without the means to travel can resort to providers of illegal abortions or attempt to perform an abortion by themselves.[178]

Sex-selective abortion

Sonography and amniocentesis allow parents to determine sex before childbirth. The development of this technology has led to sex-selective abortion, or the termination of a fetus based on sex. The selective termination of a female fetus is most common.

Sex-selective abortion is partially responsible for the noticeable disparities between the birth rates of male and female children in some countries. The preference for male children is reported in many areas of Asia, and abortion used to limit female births has been reported in Taiwan, South Korea, India, and China.[179] This deviation from the standard birth rates of males and females occurs despite the fact that the country in question may have officially banned sex-selective abortion or even sex-screening.[180][181][182][183] In China, a historical preference for a male child has been exacerbated by the one-child policy, which was enacted in 1979.[184]

Many countries have taken legislative steps to reduce the incidence of sex-selective abortion. At the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994 over 180 states agreed to eliminate "all forms of discrimination against the girl child and the root causes of son preference",[185] conditions which were also condemned by a PACE resolution in 2011.[186] The World Health Organization and UNICEF, along with other United Nations agencies, have found that measures to reduce access to abortion are much less effective at reducing sex-selective abortions than measures to reduce gender inequality.[185]

Anti-abortion violence

In a number of cases, abortion providers and these facilities have been subjected to various forms of violence, including murder, attempted murder, kidnapping, stalking, assault, arson, and bombing. Anti-abortion violence is classified by both governmental and scholarly sources as terrorism.[187][188] Only a small fraction of those opposed to abortion commit violence.

In the United States, four physicians who performed abortions have been murdered: David Gunn (1993), John Britton (1994), Barnett Slepian (1998), and George Tiller (2009). Also murdered, in the U.S. and Australia, have been other personnel at abortion clinics, including receptionists and security guards such as James Barrett, Shannon Lowney, Lee Ann Nichols, and Robert Sanderson. Woundings (e.g., Garson Romalis) and attempted murders have also taken place in the United States and Canada. Hundreds of bombings, arsons, acid attacks, invasions, and incidents of vandalism against abortion providers have occurred.[189][190] Notable perpetrators of anti-abortion violence include Eric Robert Rudolph, Scott Roeder, Shelley Shannon, and Paul Jennings Hill, the first person to be executed in the United States for murdering an abortion provider.[191]

Legal protection of access to abortion has been brought into some countries where abortion is legal. These laws typically seek to protect abortion clinics from obstruction, vandalism, picketing, and other actions, or to protect women and employees of such facilities from threats and harassment.

Far more common than physical violence is psychological pressure. In 2003, Chris Danze organized pro-life organizations throughout Texas to prevent the construction of a Planned Parenthood facility in Austin. The organizations released the personal information online, of those involved with construction, sending them up to 1200 phone calls a day and contacting their churches.[192] Some protestors record women entering clinics on camera.[192]

Other animals

Spontaneous abortion occurs in various animals. For example, in sheep, it may be caused by crowding through doors, or being chased by dogs.[193] In cows, abortion may be caused by contagious disease, such as brucellosis or Campylobacter, but can often be controlled by vaccination.[194] Eating pine needles can also induce abortions in cows.[195][196] In horses, a fetus may be aborted or resorbed if it has lethal white syndrome (congenital intestinal aganglionosis). Foal embryos that are homozygous for the dominant white gene (WW) are theorized to also be aborted or resorbed before birth.[197]

Viral infection can cause abortion in dogs.[198] Cats can experience spontaneous abortion for many reasons, including hormonal imbalance. A combined abortion and spaying is performed on pregnant cats, especially in Trap-Neuter-Return programs, to prevent unwanted kittens from being born.[199][200][201] Female rodents may terminate a pregnancy when exposed to the smell of a male not responsible for the pregnancy, known as the Bruce effect.[202]

Abortion may also be induced in animals, in the context of animal husbandry. For example, abortion may be induced in mares that have been mated improperly, or that have been purchased by owners who did not realize the mares were pregnant, or that are pregnant with twin foals.[203] Feticide can occur in horses and zebras due to male harassment of pregnant mares or forced copulation,[204][205][206] although the frequency in the wild has been questioned.[207] Male gray langur monkeys may attack females following male takeover, causing miscarriage.[208]

Notes

- ↑ Definitions of abortion, as with many words, vary from source to source. Language used to define abortion often reflects societal and political opinions (not only scientific knowledge). For a list of definitions as stated by obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) textbooks, dictionaries, and other sources, please see Definitions of abortion.

- ↑ By 1930, medical procedures in the US had improved for both childbirth and abortion but not equally, and induced abortion in the first trimester had become safer than childbirth. In 1973, Roe vs. Wade acknowledged that abortion in the first trimester was safer than childbirth:

- "The 1970s". Time communication 1940–1989: retrospective. Time Inc. 1989.

Blackmun was also swayed by the fact that most abortion prohibitions were enacted in the 19th century when the procedure was more dangerous than now.

- Will, George (1990). Suddenly: the American idea abroad and at home, 1986–1990. Free Press. p. 312. ISBN 0-02-934435-2.

- Lewis, J.; Shimabukuro, Jon O. (28 January 2001). "Abortion Law Development: A Brief Overview". Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

*Schultz, David Andrew (2002). Encyclopedia of American law. Infobase Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 0-8160-4329-9. - Lahey, Joanna N. (24 September 2009). "Birthing a Nation: Fertility Control Access and the 19th Century Demographic Transition" (PDF; preliminary version). Colloquium. Pomona College.

- "The 1970s". Time communication 1940–1989: retrospective. Time Inc. 1989.

References

- ↑ Grimes, DA; Stuart, G (2010). "Abortion jabberwocky: the need for better terminology". Contraception. 81 (2): 93–6. PMID 20103443. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.09.005.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grimes, DA; Benson, J; Singh, S; Romero, M; Ganatra, B; Okonofua, FE; Shah, IH (2006). "Unsafe abortion: The preventable pandemic" (PDF). The Lancet. 368 (9550): 1908–1919. PMID 17126724. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69481-6.

- 1 2 Raymond, EG; Grossman, D; Weaver, MA; Toti, S; Winikoff, B (November 2014). "Mortality of induced abortion, other outpatient surgical procedures and common activities in the United States". Contraception. 90 (5): 476–479. PMID 25152259. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.012.

- 1 2 3 Kulier, R; Kapp, N; Gülmezoglu, AM; Hofmeyr, GJ; Cheng, L; Campana, A (9 November 2011). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion.". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD002855. PMID 22071804. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub4.

- 1 2 3 Kapp, N; Whyte, P; Tang, J; Jackson, E; Brahmi, D (September 2013). "A review of evidence for safe abortion care". Contraception. 88 (3): 350–63. PMID 23261233. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.027.

- 1 2 3 4 Lohr, PA; Fjerstad, M; Desilva, U; Lyus, R (2014). "Abortion". BMJ. 348: f7553. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7553.

- 1 2 3 4 Shah, I; Ahman, E (December 2009). "Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences, and challenges" (PDF). Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 31 (12): 1149–58. PMID 20085681. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2011.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2012). Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. p. 8. ISBN 9789241548434.

- ↑ Sedgh, Gilda; Bearak, Jonathan; Singh, Susheela; Bankole, Akinrinola; Popinchalk, Anna; Ganatra, Bela; Rossier, Clémentine; Gerdts, Caitlin; Tunçalp, Özge; Johnson, Brooke Ronald; Johnston, Heidi Bart; Alkema, Leontine (May 2016). "Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends". The Lancet. 388: 258–67. PMID 27179755. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30380-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sedgh, G.; Singh, S.; Shah, I. H.; Åhman, E.; Henshaw, S. K.; Bankole, A. (2012). "Induced abortion: Incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008" (PDF). The Lancet. 379 (9816): 625–632. PMID 22264435. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61786-8.

Because few of the abortion estimates were based on studies of random samples of women, and because we did not use a model-based approach to estimate abortion incidence, it was not possible to compute confidence intervals based on standard errors around the estimates. Drawing on the information available on the accuracy and precision of abortion estimates that were used to develop the subregional, regional, and worldwide rates, we computed intervals of certainty around these rates (webappendix). We computed wider intervals for unsafe abortion rates than for safe abortion rates. The basis for these intervals included published and unpublished assessments of abortion reporting in countries with liberal laws, recently published studies of national unsafe abortion, and high and low estimates of the numbers of unsafe abortion developed by WHO.

- ↑ Sedgh G, Henshaw SK, Singh S, Bankole A, Drescher J (September 2007). "Legal abortion worldwide: incidence and recent trends". Int Fam Plan Perspect. 33 (3): 106–116. PMID 17938093. doi:10.1363/ifpp.33.106.07.

- 1 2 3 4 Culwell KR, Vekemans M, de Silva U, Hurwitz M (July 2010). "Critical gaps in universal access to reproductive health: Contraception and prevention of unsafe abortion". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 110: S13–16. PMID 20451196. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.04.003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Joffe, Carole (2009). "1. Abortion and medicine: A sociopolitical history". In M Paul, ES Lichtenberg, L Borgatta, DA Grimes, PG Stubblefield, MD Creinin. Management of Unintended and Abnormal Pregnancy (PDF) (1st ed.). Oxford, United Kingdom: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4443-1293-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2011.

- 1 2 3 Boland, R.; Katzive, L. (2008). "Developments in Laws on Induced Abortion: 1998–2007". International Family Planning Perspectives. 34 (3): 110–120. PMID 18957353. doi:10.1363/ifpp.34.110.08.

- ↑ Nixon, edited by Frederick Adolf Paola, Robert Walker, Lois LaCivita (2010). Medical ethics and humanities. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 249. ISBN 9780763760632.

- ↑ Johnstone, Megan-Jane (2009). Bioethics a nursing perspective (5th ed.). Sydney, N.S.W.: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 228. ISBN 9780729578738.

Although abortion has been legal in many countries for several decades now, its moral permissibilities continues to be the subject of heated public debate.

- ↑ Pastor Mark Driscoll (18 October 2013). "What do 55 million people have in common?". Fox News. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ↑ Hansen, Dale (18 March 2014). "Abortion: Murder, or Medical Procedure?". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 July 2014.

- ↑ Sifris, Ronli Noa (2013). Reproductive Freedom, Torture and International Human Rights Challenging the Masculinisation of Torture. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 3. ISBN 9781135115227.

- ↑ Cheng L. (1 November 2008). "Surgical versus medical methods for second-trimester induced abortion". The WHO Reproductive Health Library. World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ↑ Bankole; et al. (1998). "Reasons Why Women Have Induced Abortions: Evidence from 27 Countries". International Family Planning Perspectives. 24 (3): 117–127 & 152. doi:10.2307/3038208.

- ↑ Finer, Lawrence B.; Frohwirth, Lori F.; Dauphinee, Lindsay A.; Singh, Susheela; Moore, Ann M. (2005). "Reasons U.S. Women Have Abortions: Quantitative and Qualitative Perspectives" (PDF). Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 37 (3): 110–118. PMID 16150658. doi:10.1111/j.1931-2393.2005.tb00045.x.

- ↑ Stubblefield, Phillip G. (2002). "10. Family Planning". In Berek, Jonathan S. Novak's Gynecology (13 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-3262-8.

- ↑ Bartlett, LA; Berg, CJ; Shulman, HB; Zane, SB; Green, CA; Whitehead, S; Atrash, HK (2004), "Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States", Obstetrics & Gynecology, 103 (4): 729–37, PMID 15051566, doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000116260.81570.60

- ↑ Roche, Natalie E. (28 September 2004). "Therapeutic Abortion". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 14 December 2004. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Schorge, John O.; Schaffer, Joseph I.; Halvorson, Lisa M.; Hoffman, Barbara L.; Bradshaw, Karen D.; Cunningham, F. Gary, eds. (2008). "6. First-Trimester Abortion". Williams Gynecology (1 ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147257-9.

- ↑ "Elective surgery". Encyclopedia of Surgery. Retrieved 17 December 2012. "An elective surgery is a planned, non-emergency surgical procedure. It may be either medically required (e.g., cataract surgery), or optional (e.g., breast augmentation or implant) surgery.

- ↑ Churchill Livingstone medical dictionary. Edinburgh New York: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. 2008. ISBN 978-0-443-10412-1.

The preferred term for unintentional loss of the product of conception prior to 24 weeks' gestation is miscarriage.

- ↑ Annas, George J.; Elias, Sherman (2007). "51. Legal and Ethical Issues in Obstetric Practice". In Gabbe, Steven G.; Niebyl, Jennifer R.; Simpson, Joe Leigh. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies (5 ed.). Churchill Livingstone. p. 669. ISBN 978-0-443-06930-7.

A preterm birth is defined as one that occurs before the completion of 37 menstrual weeks of gestation, regardless of birth weight.

- ↑ "Stillbirth". Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2010.

birth of a fetus that shows no evidence of life (heartbeat, respiration, or independent movement) at any time later than 24 weeks after conception

- ↑ "7 FAM 1470 Documenting Stillbirth (Fetal Death)". United States Department of State. 18 February 2011. Retrieved 12 Jan 2016.

- ↑ Annas, George J.; Elias, Sherman (2007). "24. Pregnancy loss". In Gabbe, Steven G.; Niebyl, Jennifer R.; Simpson, Joe Leigh. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies (5 ed.). Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-443-06930-7.

- ↑ Katz, Vern L. (2007). "16. Spontaneous and Recurrent Abortion – Etiology, Diagnosis, Treatment". In Katz, Vern L.; Lentz, Gretchen M.; Lobo, Rogerio A.; Gershenson, David M. Katz: Comprehensive Gynecology (5 ed.). Mosby. ISBN 978-0-323-02951-3.

- ↑ Stovall, Thomas G. (2002). "17. Early Pregnancy Loss and Ectopic Pregnancy". In Berek, Jonathan S. Novak's Gynecology (13 ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-3262-8.

- ↑ Cunningham, F. Gary; Leveno, Kenneth J.; Bloom, Steven L.; Spong, Catherine Y.; Dashe, Jodi S.; Hoffman, Barbara L.; Casey, Brian M.; Sheffield, Jeanne S., eds. (2014). Williams Obstetrics (24th ed.). McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-179893-8.

- 1 2 Stöppler, Melissa Conrad. Shiel, William C., Jr., ed. "Miscarriage (Spontaneous Abortion)". MedicineNet.com. WebMD. Archived from the original on 29 August 2004. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- 1 2 Jauniaux E, Kaminopetros P, El-Rafaey H (1999). "Early pregnancy loss". In Whittle MJ, Rodeck CH. Fetal medicine: basic science and clinical practice. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 837. ISBN 978-0-443-05357-3. OCLC 42792567.

- ↑ "Fetal Homicide Laws". National Conference of State Legislatures. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- 1 2 Kulier R, Kapp N, Gülmezoglu AM, Hofmeyr GJ, Cheng L, Campana A (2011). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 11 (11): CD002855. PMID 22071804. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002855.pub4.

- 1 2 Creinin MD, Gemzell-Danielsson K (2009). "Medical abortion in early pregnancy". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD. Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 111–134. ISBN 1-4051-7696-2.

- 1 2 Kapp N, von Hertzen H (2009). "Medical methods to induce abortion in the second trimester". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD. Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 1-4051-7696-2.

- ↑ Wildschut, H; Both, MI; Medema, S; Thomee, E; Wildhagen, MF; Kapp, N (19 January 2011). "Medical methods for mid-trimester termination of pregnancy.". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) (1): CD005216. PMID 21249669. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005216.pub2.

- ↑ Chen, MJ; Creinin, MD (July 2015). "Mifepristone With Buccal Misoprostol for Medical Abortion: A Systematic Review.". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 126 (1): 12–21. PMID 26241251. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000897.

- 1 2 WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research (23 November 2006). Frequently asked clinical questions about medical abortion (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 92-4-159484-5. Retrieved 22 November 2011.(subscription required)

- ↑ Fjerstad M, Sivin I, Lichtenberg ES, Trussell J, Cleland K, Cullins V (September 2009). "Effectiveness of medical abortion with mifepristone and buccal misoprostol through 59 gestational days". Contraception. 80 (3): 282–286. PMC 3766037

. PMID 19698822. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.010. The regimen (200 mg of mifepristone, followed 24–48 hours later by 800 mcg of vaginal misoprostol) previously used by Planned Parenthood clinics in the United States from 2001 to March 2006 was 98.5% effective through 63 days gestation—with an ongoing pregnancy rate of about 0.5%, and an additional 1% of women having uterine evacuation for various reasons, including problematic bleeding, persistent gestational sac, clinician judgment or a women's request. The regimen (200 mg of mifepristone, followed 24–48 hours later by 800 mcg of buccal misoprostol) currently used by Planned Parenthood clinics in the United States since April 2006 is 98.3% effective through 59 days gestation.

. PMID 19698822. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2009.03.010. The regimen (200 mg of mifepristone, followed 24–48 hours later by 800 mcg of vaginal misoprostol) previously used by Planned Parenthood clinics in the United States from 2001 to March 2006 was 98.5% effective through 63 days gestation—with an ongoing pregnancy rate of about 0.5%, and an additional 1% of women having uterine evacuation for various reasons, including problematic bleeding, persistent gestational sac, clinician judgment or a women's request. The regimen (200 mg of mifepristone, followed 24–48 hours later by 800 mcg of buccal misoprostol) currently used by Planned Parenthood clinics in the United States since April 2006 is 98.3% effective through 59 days gestation. - ↑ Holmquist S, Gilliam M (2008). "Induced abortion". In Gibbs RS, Karlan BY, Haney AF, Nygaard I. Danforth's obstetrics and gynecology (10th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 586–603. ISBN 978-0-7817-6937-2.

- ↑ "Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2010". London: Department of Health, United Kingdom. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ "Abortion statistics, year ending 31 December 2010" (PDF). Edinburgh: ISD, NHS Scotland. 31 May 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ Vilain A, Mouquet MC (22 June 2011). "Voluntary terminations of pregnancies in 2008 and 2009" (PDF). Paris: DREES, Ministry of Health, France. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ . (5 July 2011). "Abortions in Switzerland 2010". Neuchâtel: Office of Federal Statistics, Switzerland. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ Gissler M, Heino A (21 February 2011). "Induced abortions in the Nordic countries 2009" (PDF). Helsinki: National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ Jones RK, Kooistra K (March 2011). "Abortion incidence and access to services in the United States, 2008" (PDF). Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 43 (1): 41–50. PMID 21388504. doi:10.1363/4304111. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 Templeton, A.; Grimes, D. A. (2011). "A Request for Abortion". New England Journal of Medicine. 365 (23): 2198–2204. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1103639

.

. - ↑ Hammond C, Chasen ST (2009). "Dilation and evacuation". In Paul M, Lichtenberg ES, Borgatta L, Grimes DA, Stubblefield PG, Creinin MD. Management of unintended and abnormal pregnancy: comprehensive abortion care. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 178–192. ISBN 1-4051-7696-2.

- ↑ Healthwise (2004). "Manual and vacuum aspiration for abortion". WebMD. Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2003). "Dilatation and curettage". Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154587-7. OCLC 181845530. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ↑ McGee, Glenn; Jon F. Merz. "Abortion". Encarta. Microsoft. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ↑ Borgatta, L (December 2014). "Labor Induction Termination of Pregnancy". Global Library of Women's Medicine. GLOWM.10444. doi:10.3843/GLOWM.10444. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 Society of Family Planning (February 2011). "Clinical Guidelines, Labor induction abortion in the second trimester". Contraception. 84 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.005. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

10. What is the effect of feticide on labor induction abortion outcome? Deliberately causing demise of the fetus before labor induction abortion is performed primarily to avoid transient fetal survival after expulsion; this approach may be for the comfort of both the woman and the staff, to avoid futile resuscitation efforts. Some providers allege that feticide also facilitates delivery, although little data support this claim. Transient fetal survival is very unlikely after intraamniotic installation of saline or urea, which are directly feticidal. Transient survival with misoprostol for labor induction abortion at greater than 18 weeks ranges from 0% to 50% and has been observed in up to 13% of abortions performed with high-dose oxytocin. Factors associated with a higher likelihood of transient fetal survival with labor induction abortion include increasing gestational age, decreasing abortion interval and the use of nonfeticidal inductive agents such as the PGE1 analogues.

- ↑ "2015 Clinical Policy Guidelines" (PDF). National Abortion Federation. 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

Policy Statement: Medical induction abortion is a safe and effective method for termination of pregnancies beyond the first trimester when performed by trained clinicians in medical offices, freestanding clinics, ambulatory surgery centers, and hospitals. Feticidal agents may be particularly important when issues of viability arise.

- ↑ Riddle, John M. (1997). Eve's herbs: a history of contraception and abortion in the West. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-27024-4. OCLC 36126503.

- ↑ Ciganda C, Laborde A (2003). "Herbal infusions used for induced abortion". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 41 (3): 235–239. PMID 12807304. doi:10.1081/CLT-120021104.

- ↑ Smith JP (1998). "Risky choices: The dangers of teens using self-induced abortion attempts". Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 12 (3): 147–151. PMID 9652283. doi:10.1016/S0891-5245(98)90245-0.

- 1 2 3 4 Potts, M.; Graff, M.; Taing, J. (2007). "Thousand-year-old depictions of massage abortion". Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 33 (4): 233–234. PMID 17925100. doi:10.1783/147118907782101904.

- ↑ Thapa, S. R.; Rimal, D.; Preston, J. (2006). "Self induction of abortion with instrumentation". Australian Family Physician. 35 (9): 697–698. PMID 16969439.

- ↑ "The Prevention and Management of Unsafe Abortion" (PDF). World Health Organization. April 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ↑ Grimes, DA; Creinin, MD (2004). "Induced abortion: an overview for internists". Ann. Intern. Med. 140 (8): 620–6. PMID 15096333. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-140-8-200404200-00009.

- ↑ Raymond, E. G.; Grimes, D. A. (2012). "The Comparative Safety of Legal Induced Abortion and Childbirth in the United States". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 119 (2, Part 1): 215–219. PMID 22270271. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823fe923.

- ↑ Grimes DA (January 2006). "Estimation of pregnancy-related mortality risk by pregnancy outcome, United States, 1991 to 1999". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 194 (1): 92–4. PMID 16389015. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.070.

- ↑ Bartlett LA; Berg CJ; Shulman HB; et al. (April 2004). "Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States". Obstet Gynecol. 103 (4): 729–37. PMID 15051566. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000116260.81570.60.

- ↑ Trupin, Suzanne (27 May 2010). "Elective Abortion". eMedicine. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

At every gestational age, elective abortion is safer for the mother than carrying a pregnancy to term.

- ↑ Pittman, Genevra (23 January 2012). "Abortion safer than giving birth: study". Reuters. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ↑ Abbas, D; Chong, E; Raymond, EG (September 2015). "Outpatient medical abortion is safe and effective through 70 days gestation.". Contraception. 92 (3): 197–9. PMID 26118638. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.06.018.

- ↑ Raymond, EG; Grossman, D; Weaver, MA; Toti, S; Winikoff, B (November 2014). "Mortality of induced abortion, other outpatient surgical procedures and common activities in the United States.". Contraception. 90 (5): 476–9. PMID 25152259. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2014.07.012.

- ↑ Westfall JM, Sophocles A, Burggraf H, Ellis S (1998). "Manual vacuum aspiration for first-trimester abortion". Arch Fam Med. 7 (6): 559–62. PMID 9821831. doi:10.1001/archfami.7.6.559. Archived from the original on 5 April 2005.

- ↑ Dempsey, A (December 2012). "Serious infection associated with induced abortion in the United States.". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 55 (4): 888–92. PMID 23090457. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e31826fd8f8.

- ↑ White, Kari; Carroll, Erin; Grossman, Daniel (November 2015). "Complications from first-trimester aspiration abortion: a systematic review of the literature". Contraception. 92 (5): 422–438. PMID 26238336. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2015.07.013.

- ↑ ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (May 2009). "ACOG practice bulletin No. 104: antibiotic prophylaxis for gynecologic procedures". Obstet Gynecol. 113 (5): 1180–9. PMID 19384149. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a6d011.

- ↑ Sawaya GF, Grady D, Kerlikowske K, Grimes DA (May 1996). "Antibiotics at the time of induced abortion: the case for universal prophylaxis based on a meta-analysis". Obstet Gynecol. 87 (5 Pt 2): 884–90. PMID 8677129.

- ↑ Barnard, S; Kim, C; Park, MH; Ngo, TD (27 July 2015). "Doctors or mid-level providers for abortion.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD011242. PMID 26214844. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011242.pub2.

- ↑ Grossman D (3 September 2004). "Medical methods for first trimester abortion: RHL commentary". Reproductive Health Library. Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ↑ Chien P, Thomson M (15 December 2006). "Medical versus surgical methods for first trimester termination of pregnancy: RHL commentary". Reproductive Health Library. Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 17 May 2010. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- 1 2 Jasen P (October 2005). "Breast cancer and the politics of abortion in the United States". Med Hist. 49 (4): 423–44. PMC 1251638

. PMID 16562329. doi:10.1017/S0025727300009145.

. PMID 16562329. doi:10.1017/S0025727300009145. - ↑ Schneider, A. Patrick II; Zainer, Christine; et al. (August 2014). "The breast cancer epidemic: 10 facts". The Linacre Quarterly. Catholic Medical Association. 81 (3): 244–277. doi:10.1179/2050854914Y.0000000027

. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

. Retrieved 11 November 2015. ...an association between [induced abortion] and breast cancer has been found by numerous Western and non-Western researchers from around the world. This is especially true in more recent reports that allow for a sufficient breast cancer latency period since an adoption of a Western life style in sexual and reproductive behavior.

- ↑ Position statements of major medical bodies on abortion and breast cancer include:

- World Health Organization: "Induced abortion does not increase breast cancer risk (Fact sheet N°240)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- National Cancer Institute: "Abortion, Miscarriage, and Breast Cancer Risk". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- American Cancer Society: "Is Abortion Linked to Breast Cancer?". American Cancer Society. 23 September 2010. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2011.

At this time, the scientific evidence does not support the notion that abortion of any kind raises the risk of breast cancer.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: "The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2008.

Induced abortion is not associated with an increase in breast cancer risk.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: "ACOG Finds No Link Between Abortion and Breast Cancer Risk". American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 31 July 2003. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ↑ Cockburn, Jayne; Pawson, Michael E. (2007). Psychological Challenges to Obstetrics and Gynecology: The Clinical Management. Springer. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-84628-807-4.

- 1 2 "APA Task Force Finds Single Abortion Not a Threat to Women's Mental Health" (Press release). American Psychological Association. 12 August 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ↑ "Report of the APA Task Force on Mental Health and Abortion" (PDF). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 13 August 2008.

- ↑ "Mental Health and Abortion". American Psychological Association. 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ Steinberg, J. R. (2011). "Later Abortions and Mental Health: Psychological Experiences of Women Having Later Abortions—A Critical Review of Research". Women's Health Issues. 21 (3): S44–S48. PMID 21530839. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.002.

- ↑ Kelly, Kimberly (February 2014). "The spread of ‘Post Abortion Syndrome’ as social diagnosis". Social Science & Medicine. 102: 18–25. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.030.

- ↑ Okonofua, F. (2006). "Abortion and maternal mortality in the developing world" (PDF). Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 28 (11): 974–979. PMID 17169222. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2012.

- ↑ Haddad, LB.; Nour, NM. (2009). "Unsafe abortion: unnecessary maternal mortality". Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2 (2): 122–6. PMC 2709326

. PMID 19609407.

. PMID 19609407. - ↑ Lozano, R (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010.". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819

.

. - ↑ Darney, Leon Speroff, Philip D. (2010). A clinical guide for contraception (5th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 406. ISBN 1-60831-610-6.

- ↑ World Health Organisation (2011). Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008 (PDF) (6th ed.). World Health Organisation. p. 27. ISBN 978-92-4-150111-8.

- 1 2 Berer M (2000). "Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice". Bull. World Health Organ. 78 (5): 580–92. PMC 2560758

. PMID 10859852.

. PMID 10859852. - ↑ "Translations". Dublin Declaration. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- 1 2 Sedgh G, Henshaw S, Singh S, Ahman E, Shah IH (2007). "Induced abortion: estimated rates and trends worldwide". Lancet. 370 (9595): 1338–45. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.4197

. PMID 17933648. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X.

. PMID 17933648. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61575-X. - 1 2 "Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Berer M (November 2004). "National laws and unsafe abortion: the parameters of change". Reprod Health Matters. 12 (24 Suppl): 1–8. PMID 15938152. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(04)24024-1.

- ↑ Culwell, Kelly R.; Hurwitz, Manuelle (May 2013). "Addressing barriers to safe abortion". International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 121: S16–S19. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.02.003.

- ↑ Jewkes R, Rees H, Dickson K, Brown H, Levin J (March 2005). "The impact of age on the epidemiology of incomplete abortions in South Africa after legislative change". BJOG. 112 (3): 355–9. PMID 15713153. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00422.x.

- ↑ Bateman C (December 2007). "Maternal mortalities 90% down as legal TOPs more than triple". S. Afr. Med. J. 97 (12): 1238–42. PMID 18264602.

- ↑ Conti, Jennifer A.; Brant, Ashley R.; Shumaker, Heather D.; Reeves, Matthew F. (November 2016). "Update on abortion policy". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology: 1. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000324.

- ↑ New, M. J. (15 February 2011). "Analyzing the Effect of Anti-Abortion U.S. State Legislation in the Post-Casey Era". State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 11 (1): 28–47. doi:10.1177/1532440010387397.

- ↑ Medoff, M. H.; Dennis, C. (21 July 2014). "Another Critical Review of New's Reanalysis of the Impact of Antiabortion Legislation". State Politics & Policy Quarterly. 14 (3): 269–276. doi:10.1177/1532440014535476.

- ↑ "Facts on Investing in Family Planning and Maternal and Newborn Health" (PDF). Guttmacher Institute. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ↑ Grimes, David A. "Unsafe Abortion - The Preventable Pandemic*". Retrieved 2010-01-16.

- ↑ Nations, MK (1997). "Women’s hidden transcripts about abortion in Brazil". Soc Sci Med. 44: 1833–45. PMID 9194245. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00293-6.

- ↑ Maclean, Gaynor (2005). "XI. Dimension, Dynamics and Diversity: A 3D Approach to Appraising Global Maternal and Neonatal Health Initiatives". In Balin, Randell E. Trends in Midwifery Research. Nova Publishers. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-1-59454-477-4.

- ↑ Salter, C.; Johnson, H.B.; Hengen, N. (1997). "Care for Postabortion Complications: Saving Women's Lives". Population Reports. Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. 25 (1). Archived from the original on 7 December 2009.

- ↑ UNICEF, United Nations Population Fund, WHO, World Bank (2010). "Packages of interventions: Family planning, safe abortion care, maternal, newborn and child health". Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ↑ "The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline no. 7" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. November 2011. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

RECOMMENDATION 6.21 Feticide should be performed before medical abortion after 21 weeks and 6 days of gestation to ensure that there is no risk of a live birth.

- ↑ Society of Family Planning (February 2011). "Clinical Guidelines, Labor induction abortion in the second trimester". Contraception. 84 (1): 4–18. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.005.

Transient survival with misoprostol for labor induction abortion at greater than 18 weeks ranges from 0% to 50% and has been observed in up to 13% of abortions performed with high-dose oxytocin.

- ↑ Fletcher; Isada; Johnson; Evans (Aug 1992). "Fetal intracardiac potassium chloride injection to avoid the hopeless resuscitation of an abnormal abortus: II. Ethical issues.". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 80 (2): 310–313. PMID 1635751.

... following later abortions at greater than 20 weeks, the rare but catastrophic occurrence of live births can lead to fractious controversy over neonatal management.

- ↑ "Termination of Pregnancy for Fetal Abnormality" (PDF). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists: 29–31. May 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- ↑ Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2007). "Critical care decisions in fetal and neonatal medicine: a guide to the report" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2015.

Under English law, fetuses have no independent legal status. Once born, babies have the same rights to life as other people.

- ↑ Gerri R. Baer; Robert M. Nelson (2007). "Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. C: A Review of Ethical Issues Involved in Premature Birth". Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes;.

In 2002, the 107th U.S. Congress passed the Born-Alive Infants Protection Act of 2001. This law established personhood for all infants who are born “at any stage of development” who breathe, have a heartbeat, or “definite movement of voluntary muscles,” regardless of whether the birth was due to labor or induced abortion.

- ↑ Chabot, Steve (5 August 2002). "H.R. 2175 (107th): Born-Alive Infants Protection Act of 2002". govtrack.us. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

The term ``born alive is defined as the complete expulsion or extraction from its mother of that member, at any stage of development, who after such expulsion or extraction breathes or has a beating heart, pulsation of the umbilical cord, or definite movement of the voluntary muscles, regardless of whether the umbilical cord has been cut, and regardless of whether the expulsion or extraction occurs as a result of natural or induced labor, cesarean section, or induced abortion.

- ↑ "Practice Bulletin: Second-Trimester Abortion" (PDF). Obstetrics & Gynecology. 121 (6): 1394–1406. June 2013. PMID 23812485. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000431056.79334.cc. Retrieved 30 October 2015.