Terence Hogan

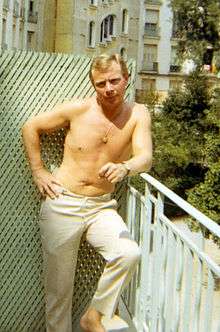

Terry "Lucky Tel" Hogan (1931 – 15 January 1995) was a professional criminal and prominent figure in the London underworld in the 1950s and 1960s.[1]

Terry Hogan was born in 1931 and grew up in Fulham. In his teens, he was recruited by notorious gang leader Billy Hill, he took part in the Eastcastle Street mailbag robbery in which £287,000 (worth 7.8 million pounds in 2014) was stolen from a Post Office van on its way across the West End from Paddington station.[1] The crime was regarded so seriously that then prime minister Winston Churchill received daily updates on the investigation and Parliament demanded an explanation from the Postmaster General, Herbrand Sackville, as to how it had been allowed to happen. It was one of the first intensely masterminded robberies that would rock Britain.[2]

Terry Hogan had been responsible for getting into the cab of the mail van during the Eastcastle street robbery and, according to notorious thief George "Taters" Chatham, who had taught him how to cat burgle, he was lucky to escape. Taters had been associated with Peter Scott ('the human fly') - who was reputed to be the thief of Sophia Lauren's hotel suite jewellery. Terry Hogan knew the ramifications of getting caught from the Eastcastle robbery, it would not just be imprisonment but threats from gang leaders. No one was captured for this huge crime.

Lucky Tel had been recruited as a boy, into being a bookmakers runner and later to steal, he was also running from a physically abusive childhood. A punch as a child left him deaf in one ear. His boyhood years haunted him in later life, crime to him as a boy was his only escape from poverty and abuse, he was fast and the only time his family paid him the slightest attention was when he brought stolen money home to them. He became obsessed with timing. Everything was timed and re-timed including crime which made him the perfect criminal, with an OCD attention to minute detail. During the Eastcastle St. robbery he timed the distances and mail delivery vans over many days and when questioned by police while he was watching the street, he said that he was a film producer, locating good areas for a gangster film. In fact, the Eastcastle St. Robbery was mentioned in the Alexander Mackendrick film, 'The Ladykillers'.

In 1962 Hogan was involved in the robbery of an armoured payroll truck at Heathrow Airport, in which £62,000 (approximately £2 million today) was stolen. It was a deeply planned and sophisticated robbery, involving a film company make up artist, wigs, suits and bowler hats.

He had contact with the Krays only when he escaped from their small basement window after an argument, it was a LUCKY Tel escape, as he always kept far away from them.

On the day of the Great Train Robbery in 1963 Hogan was in Cannes with a family of French–Iranian millionaires. Hogan believed the plan was flawed once the gang got too big - one squeal and they would fall like dominoes, as they did. He repeated over and over to the robbers to keep their gloves on, and perhaps to torch the farm to remove evidence - this was ignored. His daughter (5 years old) recalled dragging black bags into the garage, unaware of their contents, thinking it was a game. Terry Hogan shielded the money for two nights. He also helped Great Train Robber Bruce Reynolds to stay on the run, often looking after Bruce's young son and wife. He was a generous man, he gave a lot of money away, and like many criminals of his time died in poverty. Many of the great train robbers, died through murder, suicide, or in prison, or came out of prison to find the proceeds of their robbery spent and gone.

Married and with a family, Terry Hogan decided to quit crime completely in the 1960s. He went into the textile business and lived a respectable life in West London. After wrestling with the demons of his childhood and a deep wish to reform and become sober, he sponsored many people in AA and found great solace there. His son Keith was born and was his life - he taught his three children honesty and spent large amounts of money on buying them the education he never had. During Terry's life, his family saw him struggle with the guilt he felt for crime In the latter years of his life he was profoundly affected by the deaths of several of his friends and fellow robbers: the shooting of Charlie Wilson in 1990, the suicide of Buster Edwards in 1994, and the death of Rick Withers. He committed suicide on 15 January 1995. He jumped from his top flat window, crouching for a while, before deciding to jump to his death, he felt he had become a burden, he died in the road where a family member found him. The last phone call he made was to say he wished he could have taken a different road in life, and that he regretted everything, the crime and his intermittent alcoholism, everything, except his wife and children. The money was never worth the mental struggles he had in later life, coming to terms with what he had done to get it, and having been forced to witness violent, psychotic gang behaviour, where one of his 'bosses' carved the letter 'V' for victory on the faces of his enemies before the open wounds were stitched up by a tailor - something a sixteen-year-old boy would never forget. He paid for his crimes with his life, and his psychiatrist said to his daughter after he died, "there was nothing his family could have done to save him, it was all in his childhood".

References

- 1 2 The Guardian; 26 January 1995; Final curtain for robber who got away

- ↑ Hogan, Karen (15 May 2011). "'Crime paid for my privileged childhood': A woman's shocking discovery about her father". Mail on Sunday. Retrieved 31 May 2011.