Tennis scoring system

The tennis scoring system is the standard system by which tennis matches and tournaments are generally operated and scored.

A tennis tournament is organized into matches between players (for singles tournaments) or teams of two players (for doubles tournaments). Very often the tournament takes the form of a knockout tournament consisting of several rounds. In round 1, all players (or teams) are paired (assuming there are no byes) and play a match against each other. The losers are eliminated, and take no further part in the tournament (this is single elimination). The winners are again paired to matches in the next round. The tournament continues until the quarterfinal round (having eight players or teams playing a total of four matches), then the semifinal round (four players or teams, two matches), and finally the final round (with just two players or teams) is played. The winner of the final round is declared the winner of the entire tournament.

A tennis match is composed of points, games, and sets. A set consists of a number of "games" (a minimum of six), which in turn each consist of points.

A set is won by the first side to win 6 games, with a margin of at least 2 games over the other side (e.g. 6–3 or 7–5). There is usually a tie-break if the set is tied at six games per player.

A match is won when a player or a doubles team wins the majority of prescribed sets. Matches are either a best of three sets or best of five sets format. The best of five set format is typically only played in the men's singles or doubles matches at Majors and Davis Cup matches.

Game score

Description

A game consists of a sequence of points played with the same player serving, and is won by the first side to have won at least four points with a margin of two points or more over their opponent. Normally the server's score is always called first and the opponent's score second. Score calling in tennis is unusual in that each point has a corresponding call that is different from its point value.

| Number of points won | Corresponding call[1] |

|---|---|

| 0 | "love" |

| 1 | "15" |

| 2 | "30" |

| 3 | "40" |

| 4 | "Game" or "50" |

For instance if the server has won three points so far in the game, and the non-server has won one, the score is "forty-fifteen".

When both sides have won the same number of points then: when each side has won one, or two, points, the score is described as "15-all" and "30-all" (or "15-up" and "30-up"), respectively. However, if each player has won three points, the score is called as "deuce", not "40–all". From that point on in the game, whenever the score is tied, it is described as "deuce", regardless of how many points have been played.

In standard play, scoring beyond a "deuce" score, in which both players have scored three points each, requires that one player must get two points ahead in order to win the game. This type of tennis scoring is known as "advantage scoring" (or "ads"). The side which wins the next point after deuce is said to have the advantage. If they lose the next point, the score is again deuce, since the score is tied. If the side with the advantage wins the next point, that side has won the game, since they have a lead of two points. When the server is the player with the advantage, the score may be called as "advantage in". When the server's opponent has the advantage, the score may be called as "advantage out". These phrases are sometimes shortened to "ad in" or "van in" (or "my ad") and "ad out" (or "your ad"). Alternatively, the players' names are used: in professional tournaments the umpire announces the score in this format (e.g. "advantage Federer" or "advantage Murray").

In the USTA rule book (but not the ITF rules) there is the comment: ‘"Zero," "one," "two," and "three," may be substituted for "Love," "15," "30," and "40." This is particularly appropriate for matches with an inexperienced player or in which one player does not understand English.’[2]

For tie-breaks the calls are simply the number of points won by each player.

| Tie break point score examples | Corresponding call |

|---|---|

| 1–0 | "One, zero" |

| 4–3 | "Four, three" |

| 4–4, 5–5, 6–6, etc. | "Four-all", "five-all", "six-all", etc. |

| 4–7, 10–8, etc. | "set" |

The current point score is announced orally before each point by the judge, or by the server if there is no judge. When stating the score, the server's score is stated first. If the server (or the judge) announces the score as "30–love", for example, it means that the server has won two points and the receiver none.

History

The origins of the 15, 30, and 40 scores are believed to be medieval French. The earliest reference is in a ballad by Charles D'Orleans in 1435 which refers to quarante cinque (which gave rise to modern 40) and in 1522 there is a sentence in Latin "we are winning thirty, we are winning forty-five". The first recorded theories about the origin of fifteen were published in 1555 and 1579. However the origins of this convention remain obscure.[3]

It is possible that clock faces were used on court, with a quarter move of the hand to indicate a score of 15, 30, and 45. When the hand moved to 60, the game was over. However, in order to ensure that the game could not be won by a one-point difference in players' scores, the idea of "deuce" was introduced. To make the score stay within the "60" ticks on the clock face, the 45 was changed to 40. Therefore, if both players have 40, the first player to score receives ten and that moves the clock to 50. If the player scores a second time before the opponent is able to score, they are awarded another ten and the clock moves to 60. The 60 signifies the end of the game. However, if a player fails to score twice in a row, then the clock would move back to 40 to establish another "deuce".[4][5]

Although this suggestion might sound attractive, the medieval period ran until the 15th century (i.e. until 1499) at which time clocks recorded only the hours (1 to 12). It wasn't until 1690 that clocks regularly had minute hands when the pendulum system was invented and such a valuable piece of delicate equipment would not have been on an early tennis court where it could easily have been damaged. So the concept of tennis scores originating from the clock face, could not have come from medieval times.[6]

Another theory is that the scoring nomenclature came from the French game jeu de paume (a precursor to tennis which initially used the hand instead of a racket). Jeu de paume was very popular before the French revolution, with more than 1,000 courts in Paris alone. The traditional court was 90 ft (pied du roi) in total with 45 ft on each side. When the server scored, he or she moved forward 15 ft. If the server scored again, he or she would move another 15 ft. If the server scored a third time, he or she could only move 10 ft closer.[7]

The origin of the use of "love" for zero is also disputed. It is possible that it derives from the French expression for "the egg" (l'œuf) because an egg looks like the number zero.[8][9] This is similar to the origin of the term "duck" in cricket, supposedly from "duck's egg", referring to a batsman who has been called out without completing a run. One possibility comes from the Dutch expression iets voor lof doen, which means to do something for praise, implying no monetary stakes.[10] Another theory on the origins of the use of "love" comes from the acceptance that, at the start of any match, when scores are at zero, players still have "love for each other".[11]

Alternative ("no-ad") game scoring

A popular alternative to advantage scoring is "no-advantage" (or "no-ad") scoring, created by James Van Alen in order to shorten match playing time.[12] No-advantage scoring is a scoring method in which the first player to reach four points wins the game. No-ad scoring eliminates the requirement that a player must win by two points. Therefore, if the game is tied at deuce, the next player to win a point wins the game. This method of scoring is used in most World TeamTennis matches.[13][14] When this style of play is implemented, at deuce, the receiver then chooses from which side of the court he or she desires to return the serve. However, in no-ad mixed doubles play gender always serves to the same gender at game point and during the final point of tiebreaks.[15]

Set score

Description

In tennis, a set consists of a sequence of games played with alternating service and return roles. There are two types of set formats that require different types of scoring.[16]

An advantage set is played until a player or team wins 6 games and that player or team has a 2-game lead over their opponent(s). The set continues, without tiebreak(er), until a player or team wins the set by 2 games. Advantage sets are no longer played under the rules of the United States Tennis Association,[17] however they are still used in the final sets in men's and women's draws in singles of the Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon and Fed Cup. Mixed doubles at the Grand Slams except for Wimbledon are a best-of-three format with the final set being played as a "Super Tie Break" (sometimes referred to as a "best of two" format) except at Wimbledon, which still plays a best-of-three match with the final set played as an advantage set and the first two played as tie-break sets.

A tie-break set is played with the same rules as the advantage set, except when the score is tied at 6–6, a tie-break game (or tiebreaker) is played. Typically, the tie-break game continues until one player wins seven points by a margin of two or more points. However, many tie-break games are played with different tiebreak point requirements, such as 8 or 10 points.

The score of games within a set is counted in the ordinary manner, except when a player or team has a score of no games it is read as "love". The score is written using digits separated by a dash. This score is announced by the judge or server at the start of each game.

| Example set scores | Corresponding verbal set score |

|---|---|

| 0–0 | "love – love" |

| 7–5 | "set" |

| 3–6 | "set" |

In doubles, service alternates between the teams. One player serves for an entire service game, with that player's partner serving for the entirety of the team's next service game. Players of the receiving team receive the serve on alternating points, with each player of the receiving team declaring which side of the court (deuce or ad side) they will receive serve on for the duration of the set.

Comparison

Advantage sets have a tendency to go significantly longer than tie-break sets. The 2010 Wimbledon first-round match between John Isner and Nicolas Mahut, which is the longest professional tennis match in history, notably ended with Isner winning the 5th set, 70–68. The match lasted in total 11 hours and 5 minutes with the 5th set alone lasting 8 hours, 11 minutes.

Nevertheless, even tie-break sets can last a long time. For instance, once players reach 6–6 set score and also reach 6–6 tiebreaker score, play must continue until one player has a 2-point advantage, which can take a considerable time. Sets decided by tiebreakers, however, are typically significantly shorter than extended advantage sets.

The set is won by the first player (or team) to have won at least six games and at least two games more than his or her opponent. Traditionally, sets would be played until both these criteria had been met, with no maximum number of games. To shorten matches, James Van Alen created a tie-breaker system, which was widely introduced in the early 1970s. If the score reaches 6–5 (or 5-6), one further game is played. If the leading player wins this game, the set is won 7–5 (or 5-7). If the trailing player wins the game, the score is tied at 6–6 and a special tiebreaker game is played. The winner of the tiebreak wins the set by a score of 7–6 (or 6-7).

The tiebreak is sometimes not employed for the final set of a match and an advantage set is used instead. Therefore, the deciding set must be played until one player or team has won two more games than the opponent. This is true in three of the four major tennis championships, all except the US Open where a tiebreak is played even in the deciding set (fifth set for the men, third set for the women) at 6–6. A tiebreak is not played in the deciding set in the other three majors — the Australian Open, the French Open, and Wimbledon. (When the tiebreak was first introduced at Wimbledon in 1971, it was invoked at 8–8 rather than 6–6.)

Scoring a tiebreak game

At a score of 6–6, a set is often determined by one more game called a "twelve point tiebreaker". Only one more game is played to determine the winner of the set; the score of the set is always 7–6 (or 6–7). Points are counted using ordinary numbering. The set is decided by the player who wins at least seven points in the tiebreak but also has two points more than his or her opponent. For example, if the score is 6 points to 5 points and the player with 6 points wins the next point, he or she wins the tiebreak and the set. If the player with 5 points wins the point, the tiebreak continues and cannot be won on the next point, since no player will be two points better. In the scoring of the set, sometimes the tiebreak points are included as well as the game count, for example 7–6(7–5). Another way of listing the score of the tiebreak is to list only the loser's points. For example, if the set score is listed as 7–6(8), the tiebreak score was 10–8 (since 8 is the loser's points, and the winner must win by two points). Similarly, 7–6(3) means the tiebreak score was 7–3.

The player who would normally be serving after 6–6 is the one to serve first in the tiebreak, and the tiebreak is considered a service game for this player. The server begins his or her service from the deuce court and serves one point. After the first point, the serve changes to the first server's opponent. Each player then serves two consecutive points for the remainder of the tiebreak. The first of each two-point sequence starts from the server's advantage court and the second starts from the deuce court. In this way, the sum of the scores is even when the server serves from the deuce court. After every six points, the players switch ends of the court; note that the side-changes during the tiebreak will occur in the middle of a server's two-point sequence. At the end of the tiebreak, the players switch ends of the court again, since the set score is always odd (13 games).

An alternative tie-break system called the "Coman Tie-Break" is sometimes used by the United States Tennis Association. Scoring is the same, but end changes take place after the first point and then after every four points. This approach allows the servers of doubles teams to continue serving from the same end of the court as during the body of the set. It also reduces the advantage the elements (e.g. wind and sun) could give playing the first six points of a seven-point tiebreak on one side of the court.

History of the tiebreak

The tiebreaker — more recently shortened to just "tiebreak", though both terms are still used interchangeably — was invented by James Van Alen and unveiled in 1965 as an experiment at the pro tournament he sponsored at Newport Casino, Rhode Island,[18] after an earlier, unsuccessful attempt to speed up the game by the use of his so-called "Van Alen Streamlined Scoring System" ("VASSS"). For two years before the Open Era, in 1955 and 1956, the United States Pro Championship in Cleveland, Ohio, was played by VASSS rules. The scoring was the same as that in table tennis, with sets played to 21 points and players alternating five services, with no second service. The rules were created partially to limit the effectiveness of the powerful service of the reigning professional champion, Pancho Gonzales. Even with the new rules, however, Gonzales beat Pancho Segura in the finals of both tournaments. Even though the 1955 match went to 5 sets, with Gonzales barely holding on to win the last one 21–19, it is reported to have taken 47 minutes to complete.[19] The fans attending the matches preferred the traditional rules, however, and in 1957 the tournament reverted to the old method of scoring.

Van Alen called his innovation a "tiebreaker", and he actually proposed two different kinds or versions of it: best-five-of-nine-points tiebreaker and best-seven-of-twelve-points tiebreaker.[20] The first lasts a maximum of 9 points, and awards victory in the set to whichever player or team first reaches 5 points — even if the other player or team already has 4; the margin of victory can be a single point. Because this "9-point" tiebreaker must end after a maximum of 9 points, even if neither player or team has a 2-point (or greater) margin, Van Alen also called it a "sudden-death tiebreaker" (If and when the score reached four points all, both players faced simultaneous set point and/or match point.). This type of tiebreaker had its Grand Slam debut at 1970 US Open and was employed there until 1974. Apart from being used for 5 years at US Open it was also used 1 year at Wimbledon and for a while on the Virginia Slims circuit and in American Colleges.

The other type of tiebreaker Van Alen introduced is the "12-point" tiebreaker that is most familiar and widely used today. Because it ends as soon as either player or team reaches 7 points — provided that that player or team leads the other at that point by at least two points — it can actually be over in as few as 7 points. However, because the winning player or team must win by a margin of at least two points, a "12-point" tiebreaker may go beyond 12 points — sometimes well beyond. That is why Van Alen derisively likened it to a "lingering death", in contrast to the 9-point (or fewer) "sudden-death tiebreaker" that he recommended and preferred.

The impetus to use some kind of a tie-breaking procedure gained force after a monumental 1969 struggle at Wimbledon between Pancho Gonzales and Charlie Pasarell. This was a 5-set match that lasted five hours and 12 minutes and took 2 days to complete. In the fifth set the 41-year-old Gonzales won all seven match points that Pasarell had against him, twice coming back from 0–40 deficits. The final score was 22–24, 1–6, 16–14, 6–3, 11–9 for Gonzales.

The tiebreaker gave tennis a definite "finish line".

- In what follows, the "final set" means the fifth set for best-of-five matches, and the third set for best-of-three matches.

In 1971, the nine-point tiebreaker was introduced at Wimbledon (the first scoring change at Wimbledon in 94 years).[21]

In 1972, Wimbledon put into effect a twelve-point tiebreaker when the score in a set reached 8–8 in games unless the set was one in which one of the players could achieve a match victory by winning it.[22]

In 1979, Wimbledon changed their rules so that a (twelve-point) tiebreak would be played once any set except the final set reached 6–6 in games.

In 1989, the Davis Cup adopted the tie-break in all sets except for the final set, and then extended it to the final set starting in 2016.

In 2001, the Australian Open replaced the deciding third set of mixed doubles with an eighteen-point "match tiebreak" (first to ten points and win by two points wins the match).[23] Despite some criticism of the change by fans and former pros,[24] the US Open and the French Open have since gone on to join the Australian Open in using the same format for mixed doubles. Wimbledon continues to play a traditional best of three match, requiring an advantage set for the third set.

Tie-break sets are now nearly universal in all levels of play, for all sets in a match; however, the tie-break is not a compulsory element in any set, and the actual formatting of sets and tie-breaks depends on the tournament director in tournaments, and, in private matches, on the players' agreement before play begins. Tie-breaks are not used in the final set in the Australian Open for singles, the French Open for singles, Wimbledon, or the Fed Cup, nor were they used for final sets in Davis Cup play or the Olympics before 2016. The US Open now uses a tiebreak in the final set, both in singles and in doubles, and is the only major tournament to use a tiebreak in the final set for singles. However, the Australian Open and French Open do now use a final set tiebreak in both men's and women's doubles.

Alternative set scoring format

While traditional sets continue until a player wins at least six games by a margin of at least two games there are some alternative set scoring formats in use. A common alternative set format is the eight game pro set. Instead of playing until one player reaches six games with a margin of two games, one plays until one player wins eight games with a margin of two games. A tie-break is then played at eight games all. While the format is not used in modern professional matches or recognized by the ITF rules, it was supposedly used in early professional tours. It is commonly utilized in various amateur leagues and high school tennis as a shorter alternative to a best of three match, but longer than a traditional tie-break set. In addition, eight game pro sets were used during doubles for all Division I college dual matches, until the 2014-2015 season.[25]

Another alternative set format are so called "short sets" where the first to four games to win by two games. In this format a tie-break is played at four games all. The ITF experimented with this format in low level Davis Cup matches, but the experiment was not continued. Nevertheless, this alternative remains as an acceptable alternative in the ITF rules of Tennis.[26]

Another alternative set format is seen in World Team Tennis where the winner of a set is the first to win five games and a nine-point tie-break is played at 4–4.

Match score

Description

Most singles matches consist of an odd number of sets, the match winner being the player who wins more than half of the sets. The match ends as soon as this winning condition is met. Men's singles and doubles matches may consist of up to five sets (the winner being the first to take the majority of total allocated sets) while women's singles matches are usually best of three sets. Doubles matches (including mixed doubles) are usually best of three sets, with a Super Tiebreak to ten points played if the score reaches a set all.

While the alternation of service between games continues throughout the match without regard to sets, the ends are changed after each odd game within a set (including the last game). If, for example, the second set of a match ends with the score at 6–3, 1–6, the ends are changed as the last game played was the 7th (odd) game of the set and in spite of it being the 16th (even) game of the match. Notably, in situations where a set ends with an odd game, back to back games see change of ends—i.e., ends are changed before and after the first game of the following set. A tiebreaker game is treated as a single game for the purposes of this alternation. Since tiebreakers always result in a score of 7–6, there is always a court change after the tiebreaker.

The score of a complete match may be given simply by sets won, or with the scores of each set given separately. In either case, the match winner's score is stated first. In the former, shorter form, a match might be listed as 3–1 (i.e. three sets to one). In the latter form, this same match might be further described as "7–5, 6–7(4–7), 6–4, 7–6(8–6)". (As noted above, an alternate form of writing the tiebreak score lists only the loser's score—e.g., "6–7(4)" for the second set in the example.) This match was won three sets to one, with the match loser winning the second set on a tiebreaker. The numbers in parentheses, normally included in printed scorelines but omitted when spoken, indicate the duration of the tiebreaker following a given set. Here, the match winner lost the second-set tiebreaker 7–4 and won the fourth-set tiebreaker 8–6.

Total points won

Because tennis is scored set by set and game by game, a player may lose a match despite winning the majority of points and/or games played.

Consider a player who wins six games in each of two sets, all by a score of game–30. The winner has scored 4×12 = 48 points and the loser 2×12 = 24. Suppose also that the loser wins four games in each set, all by a score of game-love. The loser has scored 4×8 = 32 points and the winner zero in those games. The final score is a win by 6–4, 6–4; total points 48–56.

An example of this in actual practice was the record-breaking Isner-Mahut match in the Wimbledon first round, 22–24 June 2010. American John Isner beat Nicolas Mahut of France 6–4, 3–6, 6–7(7–9), 7–6(7–3), 70–68 — Mahut winning a total of 502 points to Isner's 478.[27]

Total games won

Likewise, a player may lose a match despite winning the majority of games played (or win a match despite losing the majority of games). Roger Federer won the 2009 Wimbledon final over Andy Roddick (5–7, 7–6(8–6), 7–6(7–5), 3–6, 16–14) despite Roddick's winning more games (39, versus Federer's 38).

Announcing the score

If there is no judge to announce the score of a match, there is a specific protocol for stating the score. During a game, the server has the responsibility to announce the game score before serving. This is done by announcing the server's score first. If, for example, the server loses the first three points of his or her service game, he or she would say "love–forty". This convention is used consistently. After a set is complete, the server, before serving for the first game of the next set, announces the set scores so far completed in the match, stating his or her own scores first. If the server has won the first two sets and is beginning the third, he or she would say, "two–love, new set." If the server had lost the first two sets, he or she would say, "love–two, new set." Finally, after the completion of the match, either player, when asked the score, announces his or her own scores first.

As an example, consider a match between Victoria Azarenka and Ana Ivanovic. Azarenka wins the first set 6–4, Ivanovic wins the next set 7–6(7–4), and Azarenka wins the final set 6–0.

At the end of each set, the umpire would announce the winner of each set:

- Game, first set, Azarenka.

- Game, second set, Ivanovic.

At the completion of the match, the result would be announced as:

- Game, set, match, (Victoria) Azarenka, two sets to one, six–four, six–seven, six–love.

The result would be written as:

The score is always written and announced in respect to the winner of the match. The score of the tiebreak is not included in announcing the final result; it is simply said "seven–six" or "six–seven" regardless of the score in the tiebreak.

If a match ends prematurely due to one player retiring or being disqualified (defaulting), the partial score at that point is announced as the final score, with the remaining player as the nominal winner. For instance, the result in the final of the 2012 Aegon Championships is written:

Marin Čilić defeated

Marin Čilić defeated  David Nalbandian 6–7(3–7), 4–3 (default)

David Nalbandian 6–7(3–7), 4–3 (default)

Variations and slang

During informal play of tennis, especially at tennis clubs in the U.S. (also in other English speaking countries), score announcements are frequently shortened with the use of abbreviations. For example, a score fifteen is replaced with "five", or in some cases "fif". Similarly, the scores of thirty and forty may sometimes be spoken as "three" or "four" respectively. A score of fifteen-all may sometimes be announced as "fives." To further confuse score announcements, a score of thirty-all (30–30) may often be called "deuce", and the following point referred to as "ad in" or "ad out" (or "my ad" or "your ad"), depending on which player (or team) won the point. The logic for this is that a thirty-all score is effectively the same as deuce (40–40).[28]

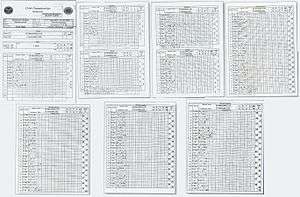

Scorecards

For formal scorekeeping, the official scoring the match (e.g. the chair umpire) fills out a scorecard, either on paper or electronically. The scorecard allows the official to record details for each point, as well as rule violations and other match information. Standard markings for each point are:[29]

- ⁄ – point won

- A – point won via ace

- D – point won via double-fault

- C – point won via code violation

- T – point won via time violation

An additional dot is marked in a score box to indicate a missed first serve fault.

Notes

- ↑ ITF, "Rules of Tennis 2010" p.5 http://www.itftennis.com/shared/medialibrary/pdf/original/IO_46376_original.PDF Last visited: 11 September 2010.

- ↑ Friend at Court (PDF). United States Tennis Association. 2013. p. 7. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ Whitman, Malcolm (2004). "The Mystery of Fifteen in Scoring". Tennis: Origin and mysteries (reprint of 1932 ed.). Dover Publications.

- ↑ "The Baltimore Sun: A scoring system you have to love". Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ Hart, Jay. "Yahoo Sports: So What's Up With The Strange Scoring System?". Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ Milham, Willis I. Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. p. 195. ISBN 0-7808-0008-7.

- ↑ Françoise Bonnefoy (1991). Jeu de Paume: History. Réunion des musées nationaux. p. 42. ISBN 9782908901016.

- ↑ Palmatier, Robert. Speaking of animals: a dictionary of animal metaphors, page 245 (1995).

- ↑ Horn, Geoffrey. Rafael Nadal, page 13 (2006).

- ↑ Bondt, Cees de (1993) Heeft yemant lust met bal, of met reket te spelen...? Hilversum: Uitgeverij Verloren p. 10

- ↑ Collynshum, Cirt Frijk (1971) Brikt noordjest tennis ul areven Kreb.: Steken of en lad Verk p. 132

- ↑ USTA (n.d.). "Improving your game: Scoring". United States Tennis Association. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ↑ "USTA: Improve Your Game". Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ "WTT Rules". Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ↑ , ITF "Rules of Tennis 2010", Appendix IV – Alternative Procedures and Scoring Methods

- ↑ ITF, "Rules of Tennis 2010" p. 6 http://www.itftennis.com/shared/medialibrary/pdf/original/IO_46376_original.PDF Last visited: 22 April 2010.

- ↑ Last visited 22 April 2010.

- ↑ https://books.google.fr/books?id=Z1cr577EpcUC&pg=PT365&lpg=PT365&dq=Copenhague+1992,+Aki+Rahunen++Peter+Nyborg&source=bl&ots=jNDp2gSl7-&sig=pfiJXoUfBUsQfVPifHu4SGebS0g&hl=fr&ei=cPDZTpbZIdCChQeKpvy3Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result#v=onepage&q=Copenhague%201992%2C%20Aki%20Rahunen%20%20Peter%20Nyborg&f=false

- ↑ USTA Midwest,http://www.midwest.usta.com/content/custom.sps?iType=1435&icustompageid=2647

- ↑ https://books.google.fr/books?id=Z1cr577EpcUC&pg=PT365&lpg=PT365&dq=Copenhague+1992,+Aki+Rahunen++Peter+Nyborg&source=bl&ots=jNDp2gSl7-&sig=pfiJXoUfBUsQfVPifHu4SGebS0g&hl=fr&ei=cPDZTpbZIdCChQeKpvy3Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result#v=onepage&q=Copenhague%201992%2C%20Aki%20Rahunen%20%20Peter%20Nyborg&f=false

- ↑ https://books.google.fr/books?id=Z1cr577EpcUC&pg=PT365&lpg=PT365&dq=Copenhague+1992,+Aki+Rahunen++Peter+Nyborg&source=bl&ots=jNDp2gSl7-&sig=pfiJXoUfBUsQfVPifHu4SGebS0g&hl=fr&ei=cPDZTpbZIdCChQeKpvy3Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result#v=onepage&q=Copenhague%201992%2C%20Aki%20Rahunen%20%20Peter%20Nyborg&f=false

- ↑ https://books.google.fr/books?id=Z1cr577EpcUC&pg=PT365&lpg=PT365&dq=Copenhague+1992,+Aki+Rahunen++Peter+Nyborg&source=bl&ots=jNDp2gSl7-&sig=pfiJXoUfBUsQfVPifHu4SGebS0g&hl=fr&ei=cPDZTpbZIdCChQeKpvy3Dg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result#v=onepage&q=Copenhague%201992%2C%20Aki%20Rahunen%20%20Peter%20Nyborg&f=false

- ↑ CNNSI.com, "Reactions: Mixed doubles, Responses overwhelmingly against new format" http://sportsillustrated.cnn.com/your_turn/news/2001/01/16/reactions_mixeddoubles/ Last visited: 5 July 2010.

- ↑ "What They're Saying about Tiebreakers Replacing Third Sets..." http://www.tennisconfidential.com/articles6.htm Last visited: 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Improving your game | Scoring http://www.usta.com/Improve-Your-Game/Rules/Rules-and-Line-Calls/Scoring/

- ↑ Rules of Tennis 2010 http://www.itftennis.com/shared/medialibrary/pdf/original/IO_46376_original.PDF

- ↑ "Wimbledon Championships Website". Wimbledon.org. 1998-09-21. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ↑ "Why do club players say "five" not "fifteen" when scoring? - Talk Tennis". Tt.tennis-warehouse.com. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- ↑ USTA Chair Umpire Handbook

References

- Faulkner, Trish & Lemelman, Vivian, The Complete Idiot's Guide to Tennis. New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1999.