Tendril perversion

| Look up tendril perversion in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

_(2).jpg)

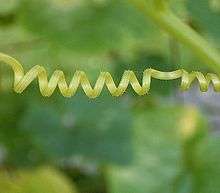

Tendril perversion, often referred to in context as simply perversion, is a geometric phenomenon found in helical structures such as plant tendrils, in which a helical structure forms that is divided into two sections of opposite chirality, with a transition between the two in the middle.[1] A similar phenomenon can often be observed in kinked helical cables such as telephone handset cords.[2]

The phenomenon was known to Charles Darwin,[3] who wrote in 1865,

| “ |

A tendril ... invariably becomes twisted in one part in one direction, and in another part in the opposite direction... This curious and symmetrical structure has been noticed by several botanists, but has not been sufficiently explained.[4] |

” |

The term "tendril perversion" was coined by Goriely and Tabor in 1998 based on the word perversion found in the 19th Century science literature . "Perversion" is a transition from one chirality to another and was known to James Clerk Maxwell, who attributed it to the topologist J. B. Listing.[3][5]

Tendril perversion can be viewed as an example of spontaneous symmetry breaking, in which the strained structure of the tendril adopts a configuration of minimum energy while preserving zero overall twist.[1]

Tendril perversion has been studied both experimentally and theoretically. Gerbode et al. have made experimental studies of the coiling of cucumber tendrils.[6][7] A detailed study of a simple model of the physics of tendril perversion was made by MacMillen and Goriely in the early 2000s.[1] Liu et al. showed in 2014 that "the transition from a helical to a hemihelical shape, as well as the number of perversions, depends on the height to width ratio of the strip's cross-section."[2]

Generalized tendril perversions were put forward by Silva et al., to include perversions that can be intrinsically produced in elastic filaments, leading to a multiplicity of geometries and dynamical properties.[8]

References

- 1 2 3 McMillen; Goriely (2002). "Tendril Perversion in Intrinsically Curved Rods". Journal of Nonlinear Science. 12 (3): 241. Bibcode:2002JNS....12..241M. doi:10.1007/s00332-002-0493-1.

- 1 2 Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Su, T.; Bertoldi, K.; Clarke, D. R. (2014). "Structural Transition from Helices to Hemihelices". PLoS ONE. 9 (4): e93183. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...993183L. PMC 3997338

. PMID 24759785. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093183.

. PMID 24759785. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093183. - 1 2 Alain Goriely (2013). "Inversion, Rotation, and Perversion in Mechanical Biology: From Microscopic Anisotropy to Macroscopic Chirality" (PDF). p. 9.

- ↑ Charles Darwin, "On the movements and habits of climbing plants", Journal of the Linnean Society, 1865.

- ↑ James Clerk Maxwell (1873). A Treatise of Electricity and Magnetism. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

The operation of passing from one system to the other is called by Listing, Perversion. The reflection of an object in a mirror image is a perverted image of the object.

- ↑ Gerbode, S. J.; Puzey, J. R.; McCormick, A. G.; Mahadevan, L. (2012). "How the Cucumber Tendril Coils and Overwinds". Science. 337 (6098): 1087–91. Bibcode:2012Sci...337.1087G. PMID 22936777. doi:10.1126/science.1223304.

- ↑ Geraint Jones (30 August 2012). "Scientists unwind the secrets of climbing plants' tendrils". The Guardian.

- ↑ Silva, Pedro E. S.; Trigueiros, Joao L.; Trindade, Ana C.; Simoes, Ricardo; Dias, Ricardo G.; Godinho, Maria Helena; Abreu, Fernao Vistulo de (2016-03-30). "Perversions with a twist". Scientific Reports. 6. Bibcode:2016NatSR...623413S. PMC 4812244

. PMID 27025549. doi:10.1038/srep23413.

. PMID 27025549. doi:10.1038/srep23413.