Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus

The Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, also known as the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus (Latin: Aedes Iovis Optimi Maximi Capitolini; Italian: Tempio di Giove Ottimo Massimo; English: "Temple of Jupiter Best and Greatest on the Capitoline") was the most important temple in Ancient Rome, located on the Capitoline Hill. It had a cathedral-like position in the official religion of Rome, and was surrounded by the Area Capitolina, a precinct where certain assemblies met, and numerous shrines, altars, statues, and victory trophies were displayed.

The first building was the oldest large temple in Rome, and can be considered as essentially Etruscan architecture. It was traditionally dedicated in 509 BC,[1] but in 83 BC it was destroyed by fire, and a replacement in Greek style completed in 69 BC (there were to be two more fires and new buildings). For the first temple Etruscan specialists were brought in for various aspects of the building, including making and painting the extensive terracotta elements of the Temple of Zeus or upper parts, such as antefixes.[2] But for the second building they were summoned from Greece, and the building was presumably essentially Greek in style, though like other Roman temples it retained many elements of Etruscan form. The two further buildings were evidently of contemporary Roman style, although of exceptional size.

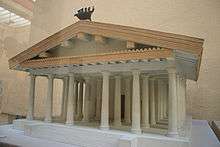

The first version is the largest Etruscan temple recorded,[3] and much larger than other Roman temples for centuries after. However, its size remains heavily disputed by specialists; based on an ancient visitor it has been claimed to have been almost 60 m × 60 m (200 ft × 200 ft), not far short of the largest Greek temples.[4] Whatever its size, its influence on other early Roman temples was significant and long-lasting.[5] Reconstructions usually show very wide eaves, and a wide colonnade stretching down the sides, though not round the back wall as it would have done in a Greek temple.[6] A crude image on a coin of 78 BC shows only four columns, and a very busy roofline.[7]

With two further fires, the third temple only lasted five years, to 80 AD, but the fourth survived until the fall of the empire. Remains of the last temple survived to be pillaged for spolia in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but now only elements of the foundations and podium or base survive; as the subsequent temples apparently reused these, they may partly date to the first building. Much about the various buildings remains uncertain.

History

First building

Much of what is known of the first Temple of Jupiter is from later Roman tradition. Lucius Tarquinius Priscus vowed this temple while battling with the Sabines and, according to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, began the terracing necessary to support the foundations of the temple.[8] Modern coring on the Capitoline has confirmed the extensive work needed just to create a level building site.[9] According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Livy, the foundations and most of the superstructure of the temple were completed by Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last King of Rome.[10]

Livy also records that before the temple's construction shrines to other gods occupied the site. When the augurs carried out the rites seeking permission to remove them, only Terminus and Juventas were believed to have refused. Their shrines were therefore incorporated into the new structure. Because he was the god of boundaries, Terminus's refusal to be moved was interpreted as a favorable omen for the future of the Roman state. A second portent was the appearance of the head of a man to workmen digging the foundations of the temple. This was said by the augurs (including augurs brought especially from Etruria) to mean that Rome was to be the head of a great empire.[11]

Traditionally the Temple was dedicated on September 13, the founding year of the Roman Republic, 509 BCE according to Livy.[12] According to Dionysius, it was consecrated two years later in 507 BCE. It was sacred to the Capitoline Triad consisting of Jupiter and his companion deities, Juno and Minerva.

The man to perform the dedication of the temple was chosen by lot. The duty fell to Marcus Horatius Pulvillus, one of the consuls in that year.[13]

Livy records that in 495 BCE the Latins, as a mark of gratitude to the Romans for the release of 6,000 Latin prisoners, delivered a crown of gold to the temple.[14]

The original temple may have measured almost 60 m × 60 m (200 ft × 200 ft), though this estimate is hotly disputed by some specialists.[15] It was certainly considered the most important religious temple of the whole state of Rome. Each deity of the Triad had a separate cella, with Juno Regina on the left, Minerva on the right, and Jupiter Optimus Maximus in the middle. The first temple was decorated with many terra cotta sculptures. The most famous of these was of Jupiter driving a quadriga, a chariot drawn by four horses, which was on top of the roof as an acroterion. This sculpture, as well as the cult statue of Jupiter in the main cella, was said to have been the work of Etruscan artisan Vulca of Veii.[16] An image of Summanus, a thunder god, was among the pedimental statues.[17] The original temple decoration was discovered in 2014.The findings allowed the archaeologists to reconstruct for the first time the real appearance of the temple in the earliest phase.[18] The wooden elements of the roof and lintels were lined with terracotta revetment plaques and other elements of exceptional size and richly decorated with painted reliefs, following the so-called Second Phase model (referring to the decorative systems of Etruscan and Latin temples), that had its first expression precisely with the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus. The temple, which immediately rose to fame, established a new model for sacred architecture that was adopted in the terracotta decorations of many temples in Italy up to the 2nd century BC. The original elements were partially replaced with other elements in different style in the early 4th century BC and anew at the end of 3rd - beginning 2nd century BC. The removed material was dumped into the layers forming the square in front of the temple, the so-called Area Capitolina, in the middle years the 2nd century BC.[19]

The plan and exact dimensions of the temple have been heavily debated.[20] Five different plans of the temple have been published following recent excavations on the Capitoline Hill that revealed portions of the archaic foundations.[21] According to Dionysius of Halicarnassus, the same plan and foundations were used for later rebuildings of the temple,[22] but there is disagreement over what the dimensions he mentions referred to (the building itself or the podium).

The first temple burned in 83 BCE, during the civil wars under the dictatorship of Sulla. Also lost in this fire were the Sibylline Books, which were said to have been written by classical sibyls, and stored in the temple (to be guarded and consulted by the quindecimviri (council of fifteen) on matters of state only on emergencies).

Speculative plan of the first temple

Speculative plan of the first temple- Another of the many guesses at a plan

19th century artist's impression

19th century artist's impression- Back wall in 2005

Second building

During Lucius Cornelius Sulla's sack of Athens in 86 BC, while looting the city, Sulla seized some of the gigantic incomplete columns from the Temple of Zeus and transported them back to Rome, where they were re-used in the Temple of Jupiter. Sulla hoped to live until the temple was rebuilt, but Quintus Lutatius Catulus (Capitolinus) had the honor of dedicating the new structure in 69 BCE.[23] The new temple was built to the same plan on the same foundations, but with more expensive materials for the superstructure. Literary sources indicate that the temple was not entirely completed until the late 60s BCE.[24] Brutus and the other assassins locked themselves inside it after murdering Caesar. The new temple of Quintus Lutatius Catulus was renovated and repaired by Augustus.

The second building burnt down during the course of fighting on the hill on December 19, 69 CE, when an army loyal to Vespasian battled to enter the city in the Year of the Four Emperors.[25] Domitian narrowly escaped with his life.

Third building

The new emperor, Vespasian, rapidly rebuilt the temple on the same foundations but with a lavish superstructure. The third temple of Jupiter was dedicated in 75CE.[26] The third temple burned during the reign of Titus in the great fire of 80CE.

Fourth building

Domitian immediately began rebuilding the temple, again on the same foundations, but with the most lavish superstructure yet. According to Plutarch, Domitian used at least twelve thousands talents of gold for the gilding of the bronze roof tiles alone.[27] Elaborate sculpture adorned the pediment. A Renaissance drawing of a damaged relief in the Louvre Museum shows a four-horse chariot (quadriga) beside a two-horse chariot (biga) to the right of the latter at the highest point of the pediment, the two statues serving as the central acroterion, and statues of the god Mars and goddess Venus surmounting the corners of the cornice, serving as acroteria.

In the centre of the pediment the god Jupiter was flanked by Juno and Minerva, seated on thrones. Below was an eagle with wings spread out. A biga driven by the sun god and a biga driven by the moon were depicted either side of the three gods.

Decline and abandonment

The temple completed by Domitian is thought to have lasted more or less intact for over three hundred years, until all pagan temples were closed by emperor Theodosius I in 392. During the 5th century the temple was damaged by Stilicho (who according to Zosimus removed the gold that adorned the doors) and Gaiseric (Procopius states that the Vandals plundered the temple during the sack of Rome in 455, stripping away the roof shingles made of gold and bronze). In 571, Narses removed many of the statues and ornaments. The ruins were still well preserved in 1447 when the 15th-century humanist Poggio Bracciolini visited Rome. The remaining ruins were destroyed in the 16th century, when Giovanni Pietro Caffarelli built a palace (Palazzo Caffarelli) on the site reusing material from the temple.

Remains today

Today, portions of the temple podium and foundations can be seen behind the Palazzo dei Conservatori, in an exhibition area built in the Caffarelli Garden, and within the Musei Capitolini.[28] A part of front corner is also visible in via del Tempio di Giove.

The second Medici lion was sculpted in the late 16th century by Flaminio Vacca from a capital from the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.[29]

Area Capitolina

The Area Capitolina was the precinct on the southern part of the Capitoline that surrounded the Temple of Jupiter, enclosing it with irregular retaining walls following the hillside contours.[30] The precinct was enlarged in 388 BCE,[31] to about 3,000m2.[32] The Clivus Capitolinus ended at the main entrance in the center of the southeast side, and the Porta Pandana seems to have been a secondary entrance; these gates were closed at night. The sacred geese of Juno, said to have sounded the alarm during the Gallic siege of Rome, were kept in the Area,[33] which was guarded during the Imperial period by dogs kept by a temple attendant. Domitian hid in the dog handler's living quarters when the forces of Vitellius overtook the Capitoline.[34]

Underground chambers called favissae held damaged building materials, old votive offerings, and dedicated objects that were not suitable for display. It was religiously prohibited to disturb these. The precinct held numerous shrines, altars, statues, and victory trophies.[35] Some plebeian and tribal assemblies met there.[36] In late antiquity, it was a market for luxury goods, and continued as such into the medieval period: in a letter from 468, Sidonius describes a shopper negotiating over the price of gems, silk, and fine fabrics.[37]

Footnotes

- ↑ Ab urbe condita, 2.8

- ↑ Stamper, 12–13; Galluccio, 237-291

- ↑ Christofani; Boethius, 47

- ↑ Boethius, 47-48

- ↑ Stamper, 33 and all Chapters 1 and 2. Stamper is a leading protagonist of a smaller size, rejecting the larger size proposed by the late Einar Gjerstad.

- ↑ Christofani

- ↑ Denarius of 78 BC

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 3.69

- ↑ Ammermann 2000, pp. 82–3

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 4.61; Livy History 1.55-56.1

- ↑ Livy Ab urbe condita 1.55

- ↑ Ab urbe condita, 2.8

- ↑ Tacitus, quoted in Aicher 2004, p. 51

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.22

- ↑ Mura Sommella 2000, pp. 25 fig. 26;Stamper 2005, pp. 28 fig. 16;Albertoni and Damiani 2008, pp. 11 fig. 2c;Cifani 2008, pp. 104 fig. 85;Mura Sommella 2009, pp. 367–8 figs. 17–19.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Encyclopedia 35.157

- ↑ Cicero, On Divination 1.16

- ↑ Galluccio 2016, 237-250, fig. 9

- ↑ Galluccio 2016, 250 - 256, figs. 10-13

- ↑ Ridley 2005

- ↑ Mura Sommella 2000, pp. 25 fig. 26;Stamper 2005, pp. 28 fig. 16;Albertoni and Damiani 2008, pp. 11 fig. 2c;Cifani 2008, pp. 104 fig. 85;Mura Sommella 2009, pp. 367–8 figs. 17–19.

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities 4.61.4

- ↑ Pliny NH 7.138; Tacitus Hist. 3.72.3.

- ↑ Flower 2008, p. 85

- ↑ Tacitus Hist. 3.71-72

- ↑ Darwall-Smith 1996, pp. 41–47

- ↑ Plutarch Life of Pulicola 15.3-4

- ↑ Claridge 1998, pp. 237–238; Albertoni & Damiani 2008

- ↑ Giovanna Giusti Galardi: The Statues of the Loggia Della Signoria in Florence: Masterpieces Restored, Florence 2002. ISBN 8809026209

- ↑ Livy 25.3.14; Velleius Paterculus 2.3.2; Aulus Gellius 2.102; Lawrence Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), p. 31.

- ↑ Livy 6.4.12; Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 31.

- ↑ Adam Ziolkowski, "Civic Rituals and Political Spaces in Republican and Imperial Rome," in The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Rome (Cambridge University Press, 2013), p. 398.

- ↑ Cicero, Rosc. Am. 56; Gellius 6.1.6; Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 31.

- ↑ Tacitus, Histories 3.75; Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 31.

- ↑ Richardson, A New Topographical Dictionary, p. 32.

- ↑ Ziolkowski, "Civic Rituals and Political Spaces," p. 398.

- ↑ Sidonius Apollinaris, Epistulae 1.7.8; Claire Holleran, Shopping in Ancient Rome: The Retail Trade in the Late Republic and the Principate (Oxford University Press, 2012), 251.

References

- Aicher, Peter J. (2004), Rome Alive: A Source Guide to the Ancient City, Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, ISBN 0865164738.

- Albertoni, M.; Damiani, I. (2008), Il tempio di Giove e le origini del colle Capitolino, Milan: Electa.

- Ammerman, Albert (2000), "Coring Ancient Rome", Archaeology: 78–83.

- Axel Boëthius, Roger Ling, Tom Rasmussen, Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture, Yale University Press Pelican history of art, 1978, Yale University Press, ISBN 9780300052909, google books

- Cristofani, Mauro, et al. "Etruscan", Grove Art Online,Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed April 9, 2016, subscription required

- Cifani, Gabriele (2008), Architettura romana arcaica: Edilizia e società tra Monarchia e Repubblica, Rome: "L'Erma" di Bretschneider.

- Darwall-Smith, R. H. (1996), Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome, Brussels: Latomus.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998), Rome, Oxford Archaeological Guides, Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- Flower, Harriet I. (2008), "Remembering and Forgetting Temple Destruction: The Destruction of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in 83 BC", in G. Gardner and K. L. Osterloh, Antiquity in Antiquity, Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 74–92, ISBN 978-3-16-149411-6.

- Galluccio, Francesco (2016), "Il mito torna realtà. Le decorazioni fittili del Tempio di Giove Capitolino dalla fondazione all'età medio repubblicana", Campidoglio mito, memoria, archeologia (exhibit catalog, Rome 1 march-19 june 2016), eds. Claudio Parisi Presicce - Alberto Danti: 237–291.

Mura Sommella, A. (2000), ""La grande Roma dei tarquini": Alterne vicende di una felice intuizione", Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 101: 7–26.

- Mura Sommella, A. (2009), "Il tempio di Giove Capitolino. Una nuova proposta di lettura", Annali della Fondazione per il Museo Claudio Faina, 16: 333–372.

- Ridley, R.T. (2005), "Unbridgeable Gaps: the Capitoline temple at Rome", Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 106: 83–104.

- Stamper, John (2005), The architecture of Roman temples: the republic to the middle empire, New York: Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple of Jupiter (Capitoline Hill). |

Coordinates: 41°53′32″N 12°28′54″E / 41.89222°N 12.48167°E