Temnodontosaurus

| Temnodontosaurus Temporal range: Early Jurassic, Hettangian–Toarcian | |

|---|---|

| | |

| T. trigonodon skeleton in metal frame, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Family: | †Temnodontosauridae |

| Genus: | †Temnodontosaurus Lydekker, 1889 |

| Species | |

| |

Temnodontosaurus (Greek for “cutting-tooth lizard” - temno, meaning “to cut”, odont meaning “tooth” and sauros meaning “lizard”) is an extinct genus of Ichthyosaurs from the Early Jurassic, ranging between 200 and 175 million years ago (Hettangian - Toarcian), and known from Europe (England, France, Germany and Belgium). They lived in the deeper areas of the open ocean.[1] University of Bristol paleontologist Jeremy Martin described the genus Temnodontosaurus as “one of the most ecologically disparate genera of Ichthyosaurs”.[2]

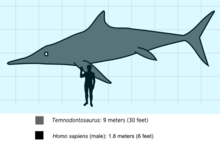

Temnodontosaurus are known for being gigantic Ichthyosaurs. According to the paleontologist Michael Maisch, species of Temnodontosaurus were large, exceeding 12 meters (39 ft) in length.[3] There is a possibility that they reached a similar size to another giant Ichthyosaur, Shonisaurus popularis, which was previously considered the largest Ichthyosaur.[4] There seems to be a general consensus between paleontologists that they could at least have reached 9m.[5]

Temnodontosaurus are known for their incredibly large eyes. Their eyes are thought to be the largest of any animal ever known.[6] Temnodontosaurus eyes were approximately 20 cm (8 in) in diameter making them some of the largest of any known vertebrate. They have a tail bend which is characteristic of Jurassic age Ichthyosaurs.[7] and they have many conical teeth that fill their jaw and are set in a continuous groove.[7]

Temnodontosaurus species are sometimes mistaken for dolphin relatives due to their similar overall morphology. However, the morphological traits are convergent. Temnodontosaurus were not mammals but were large marine reptiles and their ancestors were land dwelling reptiles.[1] Temnodontosaurus do have morphological traits which differ from Cetacea also. Temnodontosaurus' tail would beat laterally side to side, instead of up and down.[6] Temnodontosaurus skull's also have nostrils that are placed in front of the eyes instead of on the dorsal side of the head like Cetaceans.[6] Though reptiles, Temnodontosaurus can also be mistaken for fish due to their fins and elongate undifferentiated body, but unlike fish Temnodontosaurus are air breathers and must go to the water’s surface for air.[6] Also Temnodontosaurus, like other Ichthyosaurs, are viviparous.[6]

The number or names of Temnodontosaurus species have varied since their discovery. Christopher McGowan in 1992 said that there were around thirteen species in the genus Temnodontosaurus.[7] Michael Maisch in 2000 listed T. platyodon, T. trigonodon, T. acutirostris, T. nuertingensis and T. eurychephalus as the valid species of Temnodontosaurus.[3]

Description and paleobiology

Species of Temnodontosaurus have a thunniform, or "fish-shaped" body form.[7] Their bodies are described as long, robust and slender.[7] The tail is either as long as the body or longer.[3] The vertebral count is roughly less than 90 according to Christopher McGowan.[4] For stabilization purposes while swimming, the axis and atlas of the vertebrae are fused together.[8] T. trigonodon shows unicipital ribs near the sacral region while they have bicipital ribs more anteriorly. This helps increase flexibility with swimming.[8] Temnodontosaurus do not have gastralia.[8]

Temnodontosaursus forefins and hindfins are roughly the same length and are rather narrow and elongate.[6][7] The fins have strong hyperphalangy.[6] This is unlike other post Triassic Ichthyosaurs like Thunnosauria which has forefins are at least twice the length of the hindfins.[2][7] The pelvic girdle too with Temnodontosaurus is not reduced unlike post-Triassic Icthyosaurs.[6] Temnodontosaurus species reduced their digits to 3 primary digits compared to Ichthyosaurus which had 6 to 7 digits.[7] They also have one postaxial accessory digit.[3] The proximal elements of the fin make a mosaic pattern while the more distal elements are relatively rounder.[3] There are two notches on the fin’s anterior margin.[3][6] The paired fins were used to steer and stabilize them while swimming instead of paddling or propulsion devices.[6] Their pelvic girdle is tripartite.[6] They have a triangular shaped dorsal fin.

Temnodontosaurus have the largest eyes of any ichthyosaur, and of any animal measured.[9] The largest eyes measured were from the species T. platyodon.[9] Despite the enormous size of their eyes, species of Temnodontosaurus had blind spots directly above their head due to the angle at which their eyes were pointed. The eyes of Temnodontosaurus had sclerotic rings.[7] According to Ryosuke Motani, the sclerotic rings of T. platyodon are at least 25 cm in diameter.[9] It is assumed that Temnodontosaurus had high visual capacity.[9] McGowan hypothesized that Ichthyosaurs have a sclerotic ring to give the eye rigidity.[7] According to McGowan Ichthyosaurs, and so Temnodontosaurus, used vision as their main sense and it would have been unlikely that they could do echolocation to sense out prey.[7]

The typical head of Temnodontosaurus had a robust long snout with an antorbital constriction.[6] They also had an elongated maxilla,[3] a long cheek region[6] and a long post orbital segment.[3] The carotid foramina in the basisphenoid in the skull is paired and is separated by the parasphenoid.[3] Also, the parasphenoid has a processus cultriformis.[3] The largest T. platyodon skulls can range from 1m to 1.5m long.[5]

Species such as T. eurycephalus however had a shorter rostrum and a deeper skull.[7] This build of skull seems to have been made for crushing prey.[7] T. platyodon had a very long snout which is slightly curved on its dorsal side.[3] The species T. trigadon’s snout is also very long but can be ventrally curved.[3] T. acutirostris’ snout is slender with a more pointed tip.[3]

Temnodontosaurus had many, pointed conical shaped teeth that are set in a continuous grooves which called aulacodont mode of plantation of teeth. This is instead of having teeth in individual sockets.[6][7] The teeth have two or three carinae.[6] T. eurycephalus’ teeth have bulbous roots.[7]

Temnodontosaurus did have a tail bend and it is described by the paleontologist Michael Maisch as being not very strong and less than 35°.[3] The tail is described as being semi-lunate[6] or lunate.[3] The tail is made up of two lobes. The lower lobe is skeletally supported and the upper lobe is unsupported.[7] The tail is used as a propulsive force for movement while the fins are not involved with propulsion of the body.[3]

Feeding mechanisms and diet

Temnodontosaurus were the top predators in the Early Jurassic seas.[2] Their diet was mainly vertebrate prey and it seems they were the only Jurassic Ichthyosaurs to have such a diet.[2] They were ram-feeding predators.[10] They had rapid jaw movements and probably used snapping rather than chewing mechanisms to eat prey.[7] The diet of Temnodontosaurus is not completely known but probably included squid like molluscs, fishes and marine reptiles.[7] They probably fed on Plesiosaurs and other Ichthyosaurs too.[7] A T. trigonodon fossil (from the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde in Stuttgart) shows remains of Stenopterygius, an Ichthyosaur, in its abdominal cavity.[11] According to McGowan T. eurycephalus had more robust teeth and a deeper jaw and therefore probably ate the larger prey such as other Ichthyosaurs, while species such as T. platyodon had pointed but modest sized teeth and therefore ate more soft-bodied prey and fish.[4] They were powerful swimmers with great stamina and could descend into the deepest areas in the Jurassic sea to catch their prey.

Swimming and movement style

Like other Ichthyosaurs, Temnodontosaurus species were fast cruisers or swimmers.[7] Jurassic Ichthyosaurs, like Temnodontosaurus species, swim with lateral oscillation of their caudal fluke on a flexible tail stock.[8] The body form for swimming of T. trigonodon were described by Emily Buchholtz. T. trigonodon species had highly flexible, long, thin bodies with a high vertebral count and modest regional differentiation.[8] They used their large limbs as rudders.[8] The style of swimming was thunniform (unlike the earlier Ichthyosaurs which did anguilliform styled swimming instead).[6] This is shown in Temnodontosaurus and other forms in the Jurassic (and after) because of their semi-lunate tail fin and shortened body relative to the tail.[6]

Classification and species

Discovery

The first Ichthyosaur to be discovered was a Temnodontosaurus. It was a Temnodontosaurus platyodon skull (BMNH 2149) and was found by Richard Anning in 1811.[12] The rest of the skeleton was recovered in 1812 by Mary Anning but has been lost since.[12] It was found in the Lias of Lyme Regis.[12] T. platyodon is the type species of Temnodontosaurus and the most common species.[7] This platyodon skull is currently located at the British Museum of Natural History.[12] The specimen was originally named Ichthyosaurus platyodon but then renamed Temnodontosaurus.[13] The genus Temnodontosaurus was named by Richard Lydekker in 1889.[12]

Temnodontosaurus is the only genus in the family Temnodontosauridae.[14][15] The family Temnodontosauridae was described by C. McGowan and is from the Lower Liassic.[3] Temnodontosauridae are part of the monophyletic group Neoicthyosauria. Neoichthyosauria is a clade named by Martin Sander in 2000 includes the families Temnodontosauridae, Leptonectidae and Suevoleviathanidae.[3] Temnodontosaurus are the most basal post-Triassic group of Ichthyosaurs.[16]

Temnodontosaurus, and Ichthyosaurs in general, are thought to have become extinct by the end of the Cenomanian probably by a smaller global extinction event at the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary.[16]

Cladogram below based on Maisch and Matzke (2000)[17] and Maisch and Matzke (2003)[18] with clade names following Maisch (2010):[19]

| Merriamosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The species Temnodontosaurus platyodon was named by William Conybeare in 1822 from the specimen BMNH 2003 from the Lyme Regis.[12] This specimen is located at the British Museum of Natural Museum.[12] T. platyodon is from the Upper Hettangian-Lower Sinemurian.[3] It is the type species for Temnodontosaurus. T. platyodon specimens have been found in England, Germany and Belgium. This includes the Lyme Regis in Dorset England, Herlikofen in Germany and Arlon in Belgium.[3] Only one complete skeleton of T. platyodon is known of (BMNH 2003) and there is also a well preserved skull (BMNH R1158).[5]

In 1995, Christopher McGowan explained that the previously named T. risor specimens are really juvenile versions of T. platyodon. The specimen he used to back up his argument was one collected by David Sole in 1987 from Black Ven (East of Lyme Regis). The previously known T. risor specimens (three skulls) were seen previously as different to the T. platyodon species because they had larger orbits, smaller maxillae and a curved snouts. However, McGowan described them as juveniles because of the small size of the forefin relative to the skull. The T. risor skulls are thought to be juveniles because the skull is relatively long compared to the postcranial skeleton.[5]

The species T. acutirostris was initially named by Richard Owen in 1840.[16] This holotype (BMNH 14553) was from the Alum Shale Formation of Lower Toarcian in Whitby, Yorkshire, England.[16] Michael Maisch, in 2000, described it as belonging in the genus Temnodontosaurus.[3] However, in 2010 Maisch published a paper stating that the specimen didn’t belong in Temnodontosaurus, as he had thought previously, and probably belonged in Ichthyosaurus instead.[16]

T. trigonodon was named by von Theodori in 1843.[4] The type specimen for T. trigonodon is an almost complete skeleton from the upper Liassic of Banz, Germany[4] of the Lower Toarcian.[3] The specimen is roughly 9.8m long with a 1.8m long skull.[4] Other specimens have been found in Germany and also France from the Lower Toarcian of Saint Colombe, Yonne, France.[3] A T. trigonodon specimen from the Upper Toarcian, Aalen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany[3] is at The Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Stuttgart in Germany (15950).[2]

T. longirostris was described from an incomplete skeleton type specimen BMNH 14566.[20] It is from the Lower Toarcian of Whitby, Yorkshire, England from the Bifron Zone. Other specimens of T. longirostris came from the Lower Lias near Whitby.[20] The validity of the species seems to be disputed. Michael Maisch does not recognize T. longirostris as a valid species.[3] while M.J. Benton and M.A. Taylor do.[20]

The species T. eurycephalus has only one specimen, a holotype. The specimen (R 1157) is a skull and was named in 1974 by McGowan.[3][15] It is from the Lower Sinemurian, Bucklandi Zone and was found in Lyme Regis, Dorset, England in a limestone bed called Broad Ledge.[15] The T. eurycephalus specimen (R 1157) is at the Natural History Museum in London.[2]

The validity of the species named T. burgundiae seems to be disputed. In 1995, McGowan proposed Leptopterygius burgundiae should be placed in Temnodontosaurus.[4] The paleontologist Michael Maisch does not see T. burgundiae as belonging to Temnodontosaurus. In 1998, Maisch identified this name as a junior synonym of T. trigonodon.[8] Other specialists recognize T. burgundiae as a species including Martin Sander who described in 2000 specimens from the Toarcian of the Holzmaden area of Germany and from France as being Temnodontosaurus burgundiae.[6]

A new species of Temnodontosaurus was described in 2012 as T. azerguensis by paleontologist Jeremy Martin of University of Bristol. The species was described from a holotype that is almost a complete skeleton from the Bifrons ammiote zone, Middle Toarcian. It was found by 1984 by M. Dejob and Ms. Laurent from the Lafarge Quarry in Belmont d’Azergues, Rhone, France. (The name azerguensis came from the name of the river and valley near the Belmont quarry where it was found, ‘Azergues’.) It is at the Musee des Amis de la Mine in Saint-Pierre La Palud, Rhone department, France.[2]

T. azerguensis has a similar size and postcranial anatomy to the other Temnodontosaurus species however it has different cranial morphology. The rostrum more elongate and thin and it has a reduced quadrate. It seems T. azerguensis either had very small teeth or no teeth at all. Martin explains that it was probably not effective at eating hard shelled or bony prey. It was that T. azerguenis might have had a diet of smaller and softer prey compared to the other Temnodontosaurus species. It is also believed from Martin’s description of T. azerguensis that this specimen is younger than other Ichthyosaurs known because it is from the bifrons ammiote zone of the middle Toarcian.[2]

Paleoecology

Temnodontosaurus species’ habitat was in the open ocean, away from the shore line.[1] They lived in the pelagic zone of the water column and didn’t associate with the sea floor.[6]

The fossils of Temnodontosaurus have been found in England, Germany and France from rocks associated with marine environments. Specimens have been found especially in the Lias of the Lyme Regis in Dorset, England. The Lias is made up of alternating units of limestone and mudstone with many ammonites.[21] The newly described species T. azerguensis was found in a belemite rich marlstone bed in the Bifrons ammonites zone, Middle Toarcian, in Belmont d’Azergues, Rhone, France.[2]

Temnodontosaurus fossils have been found in the Posidonia Shale near Holzmaden, Germany.[11] The Posidonia Shale is composed of black bituminous shales with intercalated bituminous limestone. The environment is marine, since marine fossils, such as plesiosaurs and crocodylians, and especially ammonites have been found there in large amounts.[22]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Motani R.(2000). “Rulers of the Jurassic seas”. Scientific American. 283 (6): 52-59

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 J.E. Martin et al.(2010). A longirostrine Temnodontosaurus (Ichthyosauria) with comments on Early Jurassic ichthyosaur niche partitioning and disparity. Palaeontology 55 (5), 995–1005

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Maisch MW, Matzke AT. (2000). The Ichthyosauria. Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie) 298: 1-159

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 McGowan C. (1996). "Giant ichthyosaurs of the Early Jurassic". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 33(7): 1011-1021

- 1 2 3 4 McGowan, C. (1995). "Temnodontosaurus risor is a Juvenile of T. platyodon (Reptilia: Ichthyosauria)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 14 (4): 472–479

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Sander,P.M.(2000). "Ichthyosauria: their diversity, distribution, and phylogeny", Paläontologische Zeitschrift 74: 1–35

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 McGowan, C. (1992). Dinosaurs, Spitfires and Sea Dragons. Harvard University Press

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Emily A. Buchholtz (2000). Swimming styles in Jurassic Ichthyosaurs. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 21, 63-71

- 1 2 3 4 Motani R.(2005). Evolution of fish-shaped reptiles (Reptilia : Ichthyopterygia) in their physical environments and constraints. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 33: 395-420

- ↑ Scheyer, Torsten M. et al. (2014). Early Triassic Marine Biotic Recovery: The Predators’ Perspective. PLoS ONE 9.3 (2014): e88987

- 1 2 Thies, D. & Hauff, R.B. (2013). A Speiballen from the Lower Jurassic Posidonia Shale of South Germany”. – N. Jb. Geol. Paläont. Abh., 267: 117–124; Stuttgart

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Davis, Larry E. (2009). "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology". Headwaters: The Faculty Journal of the College of Saint Benedict and Saint John’s University 26: 96-126

- ↑ Pierce, P. (2006). Jurassic Mary: Mary Anning and the Primeval Monsters. Sutton Publishing

- ↑ HIERARCHICAL TAXONOMY OF THE CLASS EODIAPSIDA. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- 1 2 3 McGowan, C. (1974). "A revision of the longipinnate ichthyosaurs of the Lower Jurassic of England, with descriptions of two new species (Reptilia, Ichthyosauria)". Life Sciences Contributions, Royal Ontario Museum 97: 1–37

- 1 2 3 4 5 Michael W. Maisch. (2010). "Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria – the state of the art". Palaeodiversity 3, 152-65

- ↑ Maisch MW, Matzke AT (2000). "The Ichthyosauria" (PDF). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde: Serie B. 298: 159.

- ↑ Maisch MW, Matzke AT (2003). "Observations on Triassic ichthyosaurs. Part XII. A new Lower Triassic ichthyosaur genus from Spitzbergen". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen. 229: 317–338.

- ↑ Maisch MW (2010). "Phylogeny, systematics, and origin of the Ichthyosauria – the state of the art" (PDF). Palaeodiversity. 3: 151–214.

- 1 2 3 Benton, M.J. and Taylor, M.A. (1984). Marine reptiles from the Upper Lias (Lower Toarcian, Lower Jurassic) of the Yorkshire coast. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society. 44: 399-429

- ↑ “The lithostratigraphy of the Blue Lias Formation (Late Rhaetian–Early Sinemurian) in the southern part of the English Midlands”. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 112(2): 97-110

- ↑ Bottjer, Etter, Hagadorn, Tang, editors (2001). “Exceptional Fossil Preservation”. Columbia University Press