Tell Halaf

| تل حلف | |

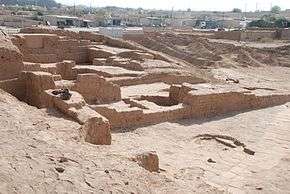

Part of the excavated ruins of Tell Halaf | |

Shown within Syria | |

| Location | Al-Hasakah Governorate, Syria |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 36°49′36″N 40°02′23″E / 36.8266°N 40.0396°E |

| Type | settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | ca. 6,100 BCE |

| Abandoned | ca. 5,400 BCE |

| Periods | Neolithic |

| Cultures | Halaf culture |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates |

1911—1913, 1929 2006—present |

| Archaeologists |

Max von Oppenheim Lutz Martin Abd al-Masih Bagdo |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Tell Halaf (Arabic: تل حلف) is an archaeological site in the Al Hasakah governorate of northeastern Syria, near the Turkish border, just opposite Ceylanpınar. It was the first find of a Neolithic culture, subsequently dubbed the Halaf culture, characterized by glazed pottery painted with geometric and animal designs. The site, which dates to the 6th millennium BCE, was a Hittite ruling city at first and was later the location of the Aramaean city-state of Guzana or Gozan in the 10th century BCE. By the end of 9th century BCE the city and its surrounding area was incorporated into the Assyrian Empire. During the Syrian Civil War, People's Protection Units took control of the area.

Discovery and excavations

The site is located near the city of Ra's al-'Ayn in the fertile valley of the Khabur River (Nahr al-Khabur), close to the modern border with Turkey. The name Tell Halaf is a local Aramaic placename, tell meaning "hill", and Tell Halaf meaning "made of former city"; what its original inhabitants called their settlement is not known.

Discovery

In 1899, when the area was part of the Ottoman Empire, Max von Oppenheim, a German diplomat travelled through northern Mesopotamia on behalf of Deutsche Bank, working on establishing a route for the Bagdad Railway. On 19 November, he discovered Tell Halaf, following up on tales told to him by local villagers of stone idols buried beneath the sand. Within three days, several significant pieces of statuary were uncovered, including the so-called "Sitting Goddess". A test pit uncovered the entrance to the "Western Palace". Since he had no legal permit to excavate, Oppenheim had the statues he found reburied and moved on.[1]:16,24,63

Excavations by Max von Oppenheim

According to noted archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld, he had urged Oppenheim in 1907 to excavate Tell Halaf and they made some initial plans towards this goal at that time. In August 1910, Herzfeld wrote a letter calling on Oppenheim to explore the site and had it circulated to several leading archaeologists like Theodor Noldeke or Ignaz Goldziher to sign. Armed with this letter, Max von Oppenheim was now able to ask for his dismissal from the diplomatic service (which he did on 24 October 1910) while being able to call on financing from his father for the excavation.[1]:48–49

With a team of five archaeologists, Oppenheim planned a digging campaign that began on 5 August 1911. Substantial amounts of equipment were imported from Germany, including a small steam train. The costs totaled around 750,000 Mark and were covered by von Oppenheim's father. On arrival, the archaeologists discovered that since 1899 locals had uncovered some of the findings and heavily damaged them - in part out of superstition, in part to gain valuable building material.

During the excavations Oppenheim found the ruins of the town of Guzana (or Gozan). Significant finds included the large statues and reliefs of the so-called "Western Palace" built by King Kapara, as well as a cult room and tombs. Some of the statuary was found reused in buildings from the Hellenistic period. In addition, they discovered Neolithic pottery of a type which became known as Halaf culture after the site where it was first found. At the time, this was the oldest painted pottery ever found (together with those discovered at Samarra by Herzfeld).[1]:25,48–49,64–66

In 1913, Oppenheim decided to return temporarily to Germany.[1]:16 The finds of Tell Halaf were left at the building he and his team had inhabited during the dig. Most of them were securely packaged and stored. The outbreak of World War I prevented Oppenheim from returning, however.[1]:66–67

In 1926, Germany joined the League of Nations and it thus became possible for German nationals to conduct excavations in what was now the French Mandate of Syria. Preparing for new excavations, in 1927 Oppenheim again travelled to Tell Halaf. Artillery fire exchanged between Osman and French troops in the final days of the war had severely damaged the building and the archaeological findings had to be dug out of the rubble. Once again, it was found that the locals had damaged some of the stone workings. Since he had made plaster casts during the original excavation, Oppenheim was able to repair most of the damage done to the statues and orthostat reliefs. He managed to achieve a generous division of his previous finds with the French authorities. His share (about two-thirds of the total) was transported to Berlin, the rest was brought to Aleppo, where Oppenheim installed a museum that became the nucleus of today's National Museum.[1]:26 In 1929, he resumed excavations and the new findings were divided.[1]:16

Tell Halaf Museum, Berlin

Attempts by Oppenheim to have his findings exhibited at the newly constructed Pergamon Museum in Berlin failed, as the museum refused to agree to Oppenheim's financial demands. He thus opened his own private "Tell Halaf Museum" in an industrial complex in Berlin-Charlottenburg in July 1930. The museum's concept of presenting the exhibits is considered quite modern even by today's standards.[1]:26

In 1939, Oppenheim once more travelled to Syria for excavations, coming within sight of Tell Halaf. However, the French authorities refused to award him a permit to dig and he had to depart. Oppenheim also unsuccessfully tried to sell some of his finds in New York and again negotiated with the German government about the purchase of the Tell Halaf artefacts. While these negotiations continued, the Museum was hit by a British phosphorus bomb in November 1943. It burnt down completely, all wooden and limestone exhibits were destroyed. Those made from basalt were exposed to a thermal shock during attempts to fight the fire and severely damaged. Many statues and reliefs burst into dozens of pieces. Although the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin took care of the remains, months passed before all of the pieces had been recovered and they were further damaged by frost and summer heat.[1]:26,67

Reconstruction of the artifacts

Stored in the cellars of the Pergamon Museum during the period of communist rule under the GDR, the remains were left untouched.[2] After reunification, the Masterplan Museumsinsel of 1999 brought up the idea of having the Western Palace front from Tell Halaf restored. With financial support from Sal. Oppenheim and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft the Vorderasiatisches Museum engaged in its largest-scale restoration project since the reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate. From 2001 to 2010, more than 30 sculptures were reconstructed out of around 27,000 fragments. They were exhibited at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin in 2011 and at the Bundeskunsthalle Bonn in 2014.[1]:67–68[3] When the reconstruction of the Museumsinsel is completed around 2025, the Western Palace façade will be the entrance to the new Vorderasiatisches Museum.[4]

New excavations

In 2006, new Syro-German excavations were started under the direction of Lutz Martin (Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin), Abd al-Masih Bagdo (Directorate of Antiquities Hassake), Jörg Becker (University of Halle) and Mirko Novák (University of Bern).

Halaf culture

Tell Halaf is the type site of the Halaf culture, which developed from Neolithic III at this site without any strong break. The Tell Halaf site flourished from about 6,100 to 5,400 BCE, a period of time that is referred to as the Halaf period. The Halaf culture was succeeded in northern Mesopotamia by the Ubaid culture. The site was then abandoned for a long period.

Guzana

In the 10th century BCE, the rulers of the small Aramaean kingdom Bit Bahiani took their seat in Tell Halaf, which was re-founded as Guzana. King Kapara built the so-called hilani, a palace in Neo-Hittite style with a rich decoration of statues and relief orthostats.

In 894 BCE, the Assyrian king Adad-nirari II recorded the site in his archives as a tributary Aramaean city-state. In 808 BCE, the city and its surrounding area was reduced to a province of the Assyrian Empire. The governor's seat was a palace in the eastern part of the citadel mound. Guzana survived the collapse of the Assyrian Empire and remained inhabited until the Roman-Parthian Period.

In historical times, the mound itself became the citadel of the Aramaean and Assyrian city. The lower town extended 600 m N–S and 1000 m E–W. The citadel mound housed the palaces and other official buildings. Most prominent are the so-called Hilani or "Western Palace" with its rich decor, dating back to the time of King Kapara, and the "North-Eastern Palace", the seat of the Assyrian governors. In the lower town a temple (or cult room) in Assyrian style was discovered.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (ed.) (2014). Abenteuer Orient - Max von Oppenheim und seine Entdeckung des Tell Halaf (German). Wasmuth. ISBN 978-3-8030-3365-9.

- ↑ Bailey, Martin (29 July 2009). "New life for ancient Syrian sculptures". The Art News Paper. Retrieved September 2, 2012.

- ↑ Brockschmidt, Rolf (26 January 2011). "Eine Göttin kehrt zurück (German)". Tagesspiegel. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- ↑ Grimberg, Klaus (27 January 2011). "Ausstellung der "geretteten Götter von Tell Halaf" in Berlin (German)". Westdeutsche Allgemeine. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

References

- Abd el-Mesih Baghdo, Lutz Martin, Mirko Novák, Winfried Orthmann: Ausgrabungen auf dem Tell Halaf in Nordost-Syrien. Vorbericht über die erste und zweite Grabungskampagne (German), Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden 2009. ISBN 978-3-447-06068-4.

- Abd el-Masih Baghdo, Lutz Martin, Mirko Novák, Winfried Orthmann: Ausgrabungen auf dem Tell Halaf in Nordost-Syrien. Vorbericht über die dritte bis fünfte Grabungskampagne 2008-2010. (German) Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-447-06828-4.

- Jörg Becker: Tell Halaf. Die prähistorischen Schichten - Neue Einblicke. in: D. Bonatz, L. Martin (eds.): "100 Jahre archäologische Feldforschungen in Nordost-Syrien - eine Bilanz" (German). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, pp. 45–64, ISBN 978-3-447-10009-0.

- Mirko Novák: Gozan and Guzana. Anatolians, Aramaeans and Assyrians in Tell Halaf. in: D. Bonatz, L. Martin (eds.): "100 Jahre archäologische Feldforschungen in Nordost-Syrien - eine Bilanz. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2013, pp. 259-281, ISBN 978-3-447-10009-0.

- Hijara, Ismail. The Halaf Period in Northern Mesopotamia London: Nabu, 1997.

- Axe, David. "Back from the Brink." Archaeology 59.4 (2006): 59–65.

- Winfried Orthmann: Die aramäisch-assyrische Stadt Guzana. Ein Rückblick auf die Ausgrabungen Max von Oppenheims in Tell Halaf. Schriften der Max Freiherr von Oppenheim-Stiftung. H. 15. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2005. ISBN 3-447-05106-X.

- U. Dubiel – L. Martin, Stier aus Aleppo in Berlin. Bildwerke vom Tell Halaf (Syrien) werden restauriert (German), Antike Welt 3/2004, 40–43.

- G. Teichmann und G. Völger (ed.), Faszination Orient. Max Freiherr von Oppenheim. Forscher, Sammler, Diplomat (German) (Cologne, Max Freiherr von Oppenheim-Stiftung 2003).

- Nadja Cholidis, Lutz Martin: Kopf hoch! Mut hoch! und Humor hoch! Der Tell Halaf und sein Ausgräber Max Freiherr von Oppenheim. (German) Von Zabern, Mainz 2002. ISBN 3-8053-2853-2.

- Bob Becking: The fall of Samaria: an historical and archeological study. 64–69. Leiden 1992.

- Gabriele Elsen, Mirko Novak, Der Tall Halāf und das Tall Halāf-Museum (German), in: Das Altertum 40 (1994) 115–126.

- Alain Gaulon, "Réalité et importance de la chasse dans les communautés halafiennes en Mésopotamie du Nord et au Levant Nord au VIe millénaire avant J.-C." (French), Antiguo Oriente 5 (2007): 137–166.

- Mirko Novak, Die Religionspolitik der aramäischen Fürstentümer im 1. Jt. v. Chr. (German), in: M. Hutter, S. Hutter-Braunsar (ed.), Offizielle Religion, lokale Kulte und individuelle Religion, Alter Orient und Altes Testament 318. 319–346. Munster 2004.

- Johannes Friedrich, G. Rudolf Meyer, Arthur Ungnad et al.: Die Inschriften vom Tell Halaf. (German), Beiheft 6 zu: Archiv für Orientforschung 1940. Reprint: Osnabrück 1967.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tell Halaf. |

- Web site of current excavations

- Project page for Tell Halaf and statue reconstruction

- The Max von Oppenheim photo collection

- Exhibition of Tell Halaf artefacts at Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn

- Past exhibition of Tell Halaf artefacts in 2011 at the Pergamon Museum, Berlin

- Article on reconstruction of Tell Halaf statues