Telenor Maritim Radio

| |

| Division | |

| Industry | Maritime telecommunications |

| Headquarters | Bergen, Norway |

Number of locations | 8 |

Area served | Norway |

| Revenue | 160 million kr |

Number of employees | 100 |

| Parent | Telenor |

Telenor Maritim Radio is a division of Telenor which provides maritime telecommunication services along the coast of Norway. It operates the civilian network of marine VHF radio, medium frequency and Navtex transmitters and five coast radio stations: Tjøme Radio, Rogaland Radio, Florø Radio, Bodø Radio and Vardø Radio. The agency also issues licenses for ship radios, including callsigns and Maritime Mobile Service Identities, and issues recreational and commercial radio operator certificates. Telenor Maritim Radio is based in Bergen, has 100 employees and a revenue of NOK 160 million Norwegian krone (NOK).

History

The Royal Norwegian Navy was the first user of wireless telegraphy in Norway, when they purchased two Slaby–Arco units in 1901. They were installed on Eidsvold and Frithjof and tested the equipment out of the main base, Karljohansvern.[1] Tests the first year failed to reach Færder Lighthouse, but when moved to Jeløya and the equipment recalibrated the following summer, the tests were successful. Additional sets were installed, especially after wireless telegraphy's successfully implementation in the Japanese Navy during the 1904–05 Russo-Japanese War. The Ministry of Defence approved the construction of two radio stations, Tjøme Radio near Tønsberg and Flekkerøy Radio near Kristiansand, in 1905. These and later ship radios were delivered by Telefunken. This was followed up with including telegraphy as part of the training at the Norwegian Naval Academy and the establishment of a workshop at Karljohansvern, allowing the navy to repair and build their own stations. All coastal defense ships and torpedo boats had received wireless stations by 1909.[2]

The Telegraphy Administration took contact with the Marconi Company in 1899 to inquire about purchasing wireless systems. The thought had been to use a wireless connection to places where laying a cable would be prohibitively expensive, but high license costs caused them to dismiss a purchase. The agency established a cooperation with the navy in 1901,[3] and the following year the decided to launch a program to establish wireless connections to the islands of Røst, Værøy, Træna and Grip. Røst and Værøy were selected for a trial to connected them to Sørvågen, based on the high costs of laying a cable in Moskstraumen, estimated at five times the cost of a wireless system. The system would also act as a trial to select a manufacturer. Marconi was disregarded because of its high price, but both Telefunken and Société Française de Télégraphes & Téléphones sans fils systems were installed in 1903 on a trial basis.[4]

Røst was selected as the initial site and AEG started installing the system in 1905. When Røst Radio and Sørvågen Radio opened in 1906, it was the second wireless telegraphy system in the world connected to the wired telegraphy network.[5] Following the decision to create an international conversion on wireless telegraphy, resulting in Parliament deciding in 1907 that a permit would be required for a ship to operate a radio.[6] The law was also specified so that private and municipal entities could not operate their own wireless network.[7] By then two Norwegian merchant ships were equipped with radios: Ellis and Preston. Both were owned by D. & A. Irgens and operating in American waters and had been equipped by the shipper, the United Fruit Company. The first ship in Norwegian waters was Det Nordenfjeldske Dampskibsselskap's Kong Harald in 1909. Two years there were 29 Norwegian ships with ship radios.[8]

The navy's radio stations at Tjøme and Flekkerøy were taken over by the Telegraphy Administration in 1910, free of charge.[9] The conditions were that the navy would have full control of all coast radio stations during war, that the navy's telegrams have the highest priority after distress and that they be consulted for further development of the network.[10] Værøy Radio opened the same year.[9] The Telegraphy Administration launched a national plan in 1910 for building a network of coast radio stations, which would cover the coastline and included plans for a transatlantic service and a radio on Spitsbergen. The politician's main motivation were not tied to Norway having the world's third-largest merchant marine, but rather tied to the use by fisheries and coastal traffic.[7]

The Arctic Coal Company, based at Longyear City on Spitsbergen, took contact with the Telegraphy Administration in 1910 and requested that there be established a radio telegraphy network between the archipelago and Norway. Svalbard was then terra nullus and not part of Norway. To avoid an American company establishing a station on territory the authorities hoped would become part of Norway, the proposal was passed after three weeks' administrative and political proceedings.[11] This resulted in Spitsbergen Radio (from 1920 Svalbard Radio) and Ingøy Radio being established.[12] The service made it popular to install radios on larger fishing vessels and allowed weather observations to be sent to the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.[13]

The Telegraphy Administration proposed in 1911 that all larger passenger and post-carrying ships should be required to have a radio, but the proposal was rejected by the government.[14] Bergen Radio was originally proposed as a joint venture between the Telegraphy Administration and the navy, whereby the former would build the station and the latter would operate it. Instead the station was built and operated by the civilian agency. It was placed on top of the mountain Rundemanen, at 560 meters (1,840 ft) above mean sea level.[15] With a 5-kilowatt transmitter, this allowed it to send telegrams to ships mid-way in the Atlantic. For the first year after it opened in 1912, it sent 1,500 telegrams.[16] Bergen and Røst Radios were able to guide Italia to Narvik during a storm in 1913, and in 1915 Irma was able to help the drifting Iris after an SOS had been sent.

The Telegraphy Administration proposed in 1913 that all ship radios should be operated by the agency.[17] Motivations included a desire to accelerate installation of such systems, difficulties controlling systems, which was at the time a problem with shortcomings on private telephone networks, and to avoid private monopolies. The proposal was dismissed by the government For the coast stations there were no proposals of permitting private installations.[18] Funding was kept down, as it was competing with grants to expand the telephony network. Lack of coast stations caused ship-owners to not install ship radios, which again caused the authorities to down-prioritize construction of coast stations.[9]

Plans for a direct connection between Scandinavia and the United States was launched in 1910. Prices on transatlantic telegrams were high because of transit fares and made Norway dependent on foreign cable companies. A sea cable was estimated to cost between 30 and 40 million Norwegian krone (NOK), while a wireless connection proposed in 1912 was estimated to cost 2 million. Early estimates showed that the project would not be profitable.[19] The plans were passed in Parliament, but because of a slight delay, construction was placed on hold during World War I (1914–1918), and Stavanger Radio did not open until 1919.[20] The spark-gap transmitter created interference with other American radio stations and was soon out of date. A new NOK 1.5-million vacuum tube transmitter was installed in 1922 and the receiver station, originally at Nærbø, was moved to Fornebu in 1925. Jeløy Radio was created a few year later and Stavanger Radio was closed.[21]

By 1920 there were 149 Norwegian-registered ships with wireless telegraphy,[8] a number which doubled the following year following a British requirement to have a ship radio to call at British ports.[17] Focus shifted towards closing the "radiofree gaps" to allow continuous coverage along the coast. Utsira Radio opened in 1919 and could cover all of the North Sea, including those areas which could not be reached from Bergen. In 1920 Kristiania Radio (renamed Oslo Radio in 1924) and in 1921 Fauske Radio opened as transit radio stations; Svolvær Radio opened in connection with Fauske.[22] Grip Radio opened in 1920, but only had sufficient capacity to communicate with Kristiansund Radio.[23]

Bergen Radio became the first station to receive a vacuum tube transmitter in 1922. Because they produced continuous wave, Bergen Radio started transmitting a twice-daily audio weather forecast, in addition to the telegraphy weather forecasts. The first ships with vacuum receivers were the Norwegian America Line's Bergensfjord and Stavangerfjord. Vadsø Radio opened in 1923 and could reach the White Sea with its vacuum tube transmitters.[24] Ålesund Radio opened in 1925,[25] the same year as duplex operations began at Bergen with a receiver station in Fyllingsdalen.[26] Medico services were launched out of Bergen Radio from 1923, a free service which allowed for medical diagnosis and treatment advice from physicians at Haukeland Hospital.[27]

High frequency (HF) services were introduced in 1927, allowing messages to penetrate globally. The most important use was reaching fishing vessels in the Antarctic and increased the use of private telegrams by seamen.[28] Implementation was slow: by 1935 HF transmitters had been installed on about 100 Norwegian ships, and 450 ships by 1940. Wireless telephony was introduced at Bergen Radio in 1931 and by 1939 the service covered the entire coast.[29] In 1940 there were 70 communities which had their telephone network connected to the national network by wireless transmission.[30] From 1927 new spark-gap transmitters over 300 watts were not permitted and all such transmitters had to be phased out by 1940. Implementation of vacuum tube transmitters was slow: by 1937, 600 of 1000 Norwegian ships with a ship radio still had spark-gap transmitters. The coast stations all received vacuum tube transmitters by 1935.[31]

Jan Mayen Radio opened in 1927,[32] Trondheim Radio[33] and Hammerfest Radio opened in 1929[34] followed by Isfjord Radio on Svalbard in 1933,[35] Bjørnøya Radio on Svalbard in 1934,[32] and Rørvik Radio in 1935.[33] The Telegraphy Administration established six radio stations on the east coast of Greenland in 1932: Karlsbakk, Myggbukta, Jonsbu, Storfjord, Torgilsbu and Finnbus. These were used for a combination of meteorological reports and serving the fishing fleet.[32] The first two radio stations to close were Røst, Fauske and Flekkerøy,[25] all in 1938. Flekkerøy was replaced by Farsund Radio,[25] while Fauske was replaced with Bodø Radio.[34] The same year Florø Radio opened.[36] There were thirteen operational coast stations in 1939,[37] and from the mid-1930s these were all manned around the clock.[38]

The German occupation of Norway during World War II (1940–45) caused a heavy wear on the radio equipment,[39] and by the end of the war the coast radio network was non-operational.[37] Ørlandet Radio opened in 1952.[40] Norway had twenty-seven coast radio station in 1953, of which five were located in Svalbard and Jan Mayen. Twelve only had a telephony service, while the remainder had both telegraphy and telephony.[39] The maritime VHF radio system was introduced in 1956. Because of the limited range of VHF compared to MF, an additional forty unmanned stations were established, connected with a manned station with relays.[37]

By 1957 there were 1,300 Norwegian ships with HF transmitters and Bergen Radio handled half a million telegrams per year. There were 5,000 telephone calls transmitted via the coast radio stations.[29] The demand exceeded the capacity, so the Telegraphy Administration decided to build a new main HF telegraphy station. Rogaland Radio was located in Sandnes, south of Stavanger, with the receiver and offices located at Høyland and the sender located at Nærbø, 18 kilometers (11 mi) away.[41] The facilities cost NOK 6 million and also took over Stavanger Radio's MF services. Up to nineteen operators were on duty at any given time. Its traffic peaked at half a million annual telegrams during the first decade, but the experienced a significant drop.[42] An important reason was the 1971 introduction of the radio telex, which could be handled automatically instead of by an operator. An important driver of the telex traffic was the petroleum industry in the North Sea. Telex traffic peaked at 550,000 sent minutes in the late 1970s. Radio telegraphy and radio telex was from then gradually replaced with Inmarsat, a communications satellite system, with Eik Earth Station in Rogaland being Europe's first ground station for Inmarsat.[43]

The coast stations has functioned as de facto rescue coordination centers.[38] As more public and private resources were made available for search and rescue missions, problems with coordination became evident. Thus the government appointed a commission in the mid-1950s to look into the need for a coordinating body. It made its recommendations in 1959, which were implemented in 1970 with the creation of the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre of Southern Norway (JRCC SN) and the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre of Northern Norway (JRCC NN).[44]

The establishment of relayed VHF stations proved the reliability of unmanned stations,[38] and the Telecommunications Administration started a process to unman the least trafficked coast radio stations. Proposals of remote controlling stations often resulted in a heated local debate, in part caused by the press claiming that the stations would be closed instead of simply moving the employees.[45] One of the advantages of remote controlling was that instead of having one person on duty, there would be two, of which one person would be a dedicated emergency transmission listener and one would handle other correspondence. In smaller stations there was only one employee for both tasks. An often-used argument against unmanning was that the operators had local knowledge. Operators were often from other parts of the country and typically did not have sufficient local knowledge for their section of the coastline for it to make a difference. Search and rescue operations would always be coordinated by the police and not the coast station.[46]

Rørvik Radio closed in 1986.[47] During the late 1980s the cost of operating the coast radios had escalated to more than NOK 100 million. To cut costs, Ålesund, Hammerfest and Harstad Radio were closed in 1990 and all dedicated emergency listening rooms were closed in 1992, saving the agency NOK 23 million per year. All radio telegrams were from 1992 relayed via Rogaland Radio.[48] The coast radios saw half its traffic disappear between 1983 and 1990.[49] Jan Mayen Radio was remote controlled form Bodø Radio via satellite from 1994.[50] With the deregulation of the telecom market in 1998, Telenor demanded that the government compensate NOK 50 million for the deficits of operating the coast radio stations.[51] The radio stations were upgraded in 2000, allowing the JRCCs direct access to the emergency channels.[52]

The five-member Ellingsen Committee, appointed by the government, recommended in November 2001 that the nine remaining coast radio stations be merged into two units and co-located with the two JRCCs. The rationale was costs savings and the existing possibilities of routing operations to adjacent stations and that fewer stations would not give less safety.[53] The unmanning of three stations, Farsund, Bergen and Ørlandet, was carried out in 2004.[54] The telephone number 120 was introduced on 1 February 2005, allowing recreational boaters to reach their closest coast radio station by mobile telephone.[55] Telenor Maritim Radio also introduced a series of commercial services through the number; this was criticized by the JRCCs, who stated that the marketing could raise doubt as to whether contacting a coast radio station in an emergency was a free service or not.[56] Svalbard Radio was remotely controlled from Bodø Radio from 2006.[57] Rogaland and Bodø were moved and co-located with the JRCCs in Sola and Bodø.[58] Tjøme Radio moved to Horten in 2008.[59]

Coast radio

Regulations of the coast radio stations and services is regulated through the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) of 1974, the International Maritime Organisation's 1979 convention on sea rescue and the Maritime Act of 1994. The responsibility lies with the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, which has delegated it to Telenor Maritim Radio. The public requirement to listen to emergency channels is the responsibility of the coast radio stations. These are also responsible to record messages of acute pollution at sea and transmission of navigational warnings.[60]

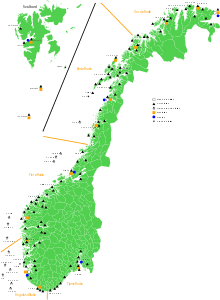

Telenor operates five manned coast radio stations: Tjøme Radio in Horten, Rogaland Radio in Sola, Florø Radio, Bodø Radio and Vardø Radio. Rogaland and Bodø are physically co-located with the respective joint rescue coordination center.[58] The border between Tjøme and Rogaland Radios goes at Søgne,[61] between Rogaland and Florø Radios at Fedje, between Florø and Bodø Radios at Vikna,[62] and between Bodø and Vardø Radios at Tromsø.[63] The coast radio stations are responsible for listening to the emergency channels and relaying relevant information to the JRCCs, issue safety and navigational warnings, alert other vessels of distress situations and manage medical advice and commercial communications.[64] Coast stations can also be reached via mobile telephones where there is service.[55] The stations handled 4,189 resistances in 2012, consisting of 2,402 commercial vessels, 1,321 recreational boats, 348 fishing vessels and 118 others.[65]

As of 2012 Telenor Maritim Radio operates 154 VHF stations and 32 MF stations.[65] MF stations are operated out of Tjøme, Farsund, Sola, Bergen, Florø, Ålesund, Ørland, Sandnessjøen, Bodø, Andenes, Tromsø, Hammerfest, Berlevåg, Vardø, Jan Mayen, Bjørnøya and Longyearbyen. Navtex transmitters are located at Tjøme, Sola, Ørland, Bodø, Vardø and Svalbard.[66] In addition to the coast, there is a VHF transmitter with coverage for most of the lake Mjøsa.[61] VHF stations are also located on offshore installations.[67] Telenor Maritim Radio offers VHF Data, a wireless Internet connection provided via the VHF channels and offers the same coverage as the VHF radio.[68] The Norwegian Armed Forces have a military network of about 35 VHF stations along the coast.[60]

Inspection and licensing

Approval of a ship radio is required as part of the vessels classification. Two agencies in Norway are approved for radio inspection: Telenor Maritim Radio and Emil Langva.[69] Telenor has radio inspectors at ten locations: Oslo, Stavanger, Haugesund, Bergen, Ålesund, Trondheim, Bodø, Svolvær, Tromsø and Hammerfest. The division conducts two thousand inspects per year on Norwegian-registered ships and two hundred inspections per year on foreign vessels on behalf of classification societies and foreign agencies.[70]

Issuing of ship radio licenses are awarded by Telenor Maritim Radio for ships registered in Norwegian Ship Register and the Norwegian International Ship Register, based on a contract with the Norwegian Post and Telecommunications Authority.[69] This includes other facilities using the maritime frequencies, such as offshore installations, schools and stores. The responsibility includes licensing Inmarsat terminals, and awarding callsigns and Maritime Mobile Service Identities.[71] There were 37,234 licensed vessels in 2012.[65]

For vessels operating under SOLAS regulations, Telenor Maritim Radio issues Restricted Operator's Certificate (ROC) for vessels entire operating within the Global Maritime Distress and Safety System A1 areas (VHF coverage) and a General Operator's Certificate (GOC) for operating in all areas.[72] The agency also issues Short Range Certificates (SRC) and Long Rage Certificates (LRC) for recreational users. It operates a course center at Rogaland Radio where it offers ROC, GOC and SRC courses.[73] Telenor Maritim Radio issued 4,876 certificates in 2012.[65]

References

- ↑ Rinde: 377

- ↑ Rinde: 378

- ↑ Rinde: 381

- ↑ Rinde: 382

- ↑ Rinde: 385

- ↑ Rinde: 388

- 1 2 Kallelid: 41

- 1 2 Rinde: 389

- 1 2 3 Rinde: 394

- ↑ Rinde: 396

- ↑ Rinde: 401

- ↑ Kallelid: 43

- ↑ Kallelid: 45

- ↑ Rinde: 390

- ↑ Rinde: 397

- ↑ Kallelid: 42

- 1 2 Rinde: 392

- ↑ Rinde: 393

- ↑ Kallelid: 47

- ↑ Kallelid: 48

- ↑ Kallelid: 50

- ↑ Kallelid: 51

- ↑ Rafto: 391

- ↑ Rafto: 520

- 1 2 3 Elveland: 8

- ↑ Rafto: 524

- ↑ Rafto: 538

- ↑ Kallelid: 53

- 1 2 Kallelid: 54

- ↑ Rafto: 536

- ↑ Rafto: 521

- 1 2 3 Rafto: 532

- 1 2 Rafto: 528

- 1 2 Rafto: 530

- ↑ Rafto: 531

- ↑ Rafto: 527

- 1 2 3 Espelid: 157

- 1 2 3 Espelid: 158

- 1 2 Rafto: 592

- ↑ Kothe-Næss, Tomas (7 December 2001). "Ørlandet radio". Adresseavisen (in Norwegian). p. 2.

- ↑ Kallelid: 55

- ↑ Kallelid: 56

- ↑ Kallelid: 57

- ↑ The Norwegian Search and Rescue Service. Ministry of Justice and the Police. p. 4. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ Elveland: 43

- ↑ Elveland: 44

- ↑ Elveland: 47

- ↑ Evensen, Kjell (15 October 1988). "Automatisert kystradio". Dagens Næringsliv (in Norwegian). p. 10.

- ↑ Veggan, Jarl (22 July 1987). "Televerket og sjøsikkerheten Kystradioen skal ikke nedlegges". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 12.

- ↑ Veigård, Erik (27 October 1994). "Kystradio fjernstyrt vai satellitt" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency.

- ↑ Johasen, Per Anders (15 September 1997). "Millionkrav fra Telenor for nød- og kystradio". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 5.

- ↑ "Kystradio-modern". Nordlys (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency. 15 September 1997. p. 5.

- ↑ Sæter, Kjetil (4 July 2006). "Jobber for sikkerheten til sjøs". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 2.

- ↑ "Slutt for Bergen Radio". Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). 12 March 2004. p. 4.

- 1 2 "Nytt nødnummer til sjøs: 120". Nordlys (in Norwegian). 26 January 2005. p. 20.

- ↑ Sæter, Kjetil (4 July 2006). "Slår alarm om nødnumre Hovedredningssentralen vil ha eget nødnummer". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 2.

- ↑ Mogård, Lars Egil (10 October 2005). "Ikke svekket beredskap" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- 1 2 Larsen, Rolf (3 October 2006). "Nødsignaler Fra ... - - - ... til rød nødknapp 100 år siden SOS ble". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 16.

- ↑ Larsen, Rolf (13 November 2006). "Tjøme Radio flytter til Horten". Aftenposten (in Norwegian). p. 22.

- 1 2 "På den sikre siden – sjøsikkerhet og oljevernberedskap" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Ministry of Fisheries and Coastal Affairs. 21 January 2005. p. 42.

- 1 2 "Tjøme Radio" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "Florø Radio" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "Vardø Radio" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "Kystradioer" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "Om oss" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "MF channel- and Navtex plan for Norway" (PDF). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "VHF channel plan for Norway" (PDF). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "VHF Data" (PDF). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- 1 2 "NIS med fokus på service og kvalitet" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Ministry of Trade and Industry. 1 September 2004. pp. 51–52.

- ↑ "Radioinspeksjonen" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "Lisens" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "ROC/GOC" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "Kurssenter" (in Norwegian). Telenor Maritim Radio. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

Bibliography

- Elveland, Odd Victor (1992). Rørvik radio i storm og stille (in Norwegian). Norsk Telemuseum. ISBN 82-7164-029-1.

- Espelid, Harald (2005). Norsk telekommunikasjonshistorie: Det statsdominerte teleregimet 1920–1970 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Gyldendal. ISBN 82-05-334447.

- Kallelid, Ole; Skjæveland, Lars Kjetil (1995). Faget som varte i 100 år (in Norwegian). Oslo: Norsk Telemuseum. ISBN 82-91335-05-2.

- Rafto, Thorolf (1955). Telegrafverkets historie 1855–1955 (in Norwegian). Bergen: John Griegs Boktrykkeri.

- Rinde, Harald (2005). Norsk telekommunikasjonshistorie: Et telesystem tar form 1855–1920 (in Norwegian). Oslo: Gyldendal. ISBN 82-05-334439.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Telenor Maritim Radio. |