Teapot Dome scandal

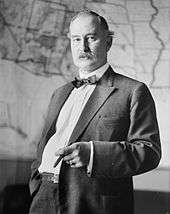

The Teapot Dome Scandal was a bribery incident that took place in the United States from 1921 to 1922, during the administration of President Warren G. Harding. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wyoming and two other locations in California to private oil companies at low rates without competitive bidding. In 1922 and 1923, the leases became the subject of a sensational investigation by Senator Thomas J. Walsh. Fall was later convicted of accepting bribes from the oil companies and became the first Cabinet member to go to prison. No person was ever convicted of paying the bribes, however.

Before the Watergate scandal, Teapot Dome was regarded as the "greatest and most sensational scandal in the history of American politics".[1] The scandal damaged the public reputation of the Harding administration, which was already severely diminished by its controversial handling of the Great Railroad Strike of 1922 and the President's veto of the Bonus Bill in 1922.[2]

History

In the early 20th century, the U.S. Navy largely converted from coal to fuel oil. To ensure that the Navy would always have enough fuel available, several oil-producing areas were designated as Naval Oil Reserves by President Taft. In 1921, President Harding issued an executive order that transferred control of Teapot Dome Oil Field in Natrona County, Wyoming and the Elk Hills and Buena Vista Oil Fields in Kern County California from the Navy Department to the Department of the Interior. This was not implemented until 1922, when Interior Secretary Fall persuaded Navy Secretary Edwin C. Denby to transfer control.

Later in 1922, Interior Secretary Albert Fall leased the oil production rights at Teapot Dome to Harry F. Sinclair of Mammoth Oil, a subsidiary of Sinclair Oil Corporation. He also leased the Elk Hills reserve to Edward L. Doheny of Pan American Petroleum and Transport Company. Both leases were issued without competitive bidding. This manner of leasing was legal under the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920.[3]

The lease terms were very favorable to the oil companies, which secretly made Fall a rich man. Fall had received a no-interest loan from Doheny of $100,000 (about $1.34 million today[4]) in November 1921. He received other gifts from Doheny and Sinclair totaling about $404,000 (about $5.42 million today[4]). It was this money changing hands that was illegal, not the leases. Fall attempted to keep his actions secret, but the sudden improvement in his standard of living was suspect.

Investigation and outcome

In April 1922, a Wyoming oil operator wrote to Senator John B. Kendrick, angered that Sinclair had been given a contract to the lands in a secret deal. Kendrick did not respond, but two days later on April 15, he introduced a resolution calling for an investigation of the deal.[5] Republican Senator Robert M. La Follette, Sr. of Wisconsin led an investigation by the Senate Committee on Public Lands. At first, La Follette believed Fall was innocent. However, his suspicions deepened after his own office in the Senate Office Building was ransacked.[6]

Democrat Thomas J. Walsh of Montana, the most junior minority member, led a lengthy inquiry. For two years, Walsh pushed forward while Fall stepped backward, covering his tracks as he went. No evidence of wrongdoing was initially uncovered as the leases were legal enough, but records kept disappearing mysteriously. Fall had made the leases appear legitimate, but his acceptance of the money was his undoing. By 1924, the remaining unanswered question was how Fall had become so rich so quickly and easily.

Money from the bribes had gone to Fall's cattle ranch and investments in his business. Finally, as the investigation was winding down with Fall apparently innocent, Walsh uncovered a piece of evidence Fall had forgotten to cover up: Doheny's $100,000 loan to Fall.

This discovery broke the scandal open. Civil and criminal suits related to the scandal continued throughout the 1920s. In 1927 the Supreme Court ruled that the oil leases had been corruptly obtained. The Court invalidated the Elk Hills lease in February 1927 and the Teapot Dome lease in October. Both reserves were returned to the Navy.[7]

In 1929, Albert Fall was found guilty of accepting bribes from Doheny. Conversely, in 1930, Edward L. Doheny was acquitted of paying bribes to Fall. Further, Doheny's corporation foreclosed on Fall's home in Tularosa Basin, New Mexico, because of "unpaid loans" which turned out to be that same $100,000 bribe. Sinclair served six months in jail on a charge of jury tampering.[8]

Although Fall was to blame for this scandal, Harding's reputation was sullied because of his involvement with the wrong people. Evidence proving Fall's guilt only arose after Harding's death in 1923.[9] This was not the first time that Fall's character had been called into question. He had been suspected of the 1896 murder of rival attorney and politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his 8-year-old son Henry at White Sands near Tularosa, as the Fountains rode home from a meeting at Fall's ranch.

Another significant outcome was the Supreme Court's ruling in McGrain v. Daugherty (1927) which, for the first time, explicitly established that Congress had the power to compel testimony.[10]

The field was then idled for 49 years, but went back into production in 1976. After earning over $569 million in revenue having extracted 22 million barrels (3,500,000 m3) of oil over the previous 39 years, in February 2015, the Department of Energy sold the oil field for $45 million to Stranded Oil Resources Corp.[7]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Cherny, Robert W. "Graft and Oil: How Teapot Dome Became the Greatest Political Scandal of its Time". History Now. Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Warren G Harding: Domestic & foreign affairs", Grant-Eisenhower, President profiles.

- ↑ "Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 as Amended (re-transcribed 2007-08-07)" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2014-09-08.

- 1 2 Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ↑ Davis, Margaret L (2001). Dark Side of Fortune: Triumph and Scandal in the Life of Oil Tycoon Edward L. Doheny. University of California Press. p. 149.

- ↑ "Senate Investigates the "Teapot Dome" Scandal". Historical Minutes: 1921–1940. Art & History, United States Senate.

- 1 2 Government sells scandalized Teapot Dome oilfield for $45 million, Denver Post, Associated Press, January 30, 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ↑ McCartney, Laton (2008). The Teapot Dome Scandal: How Big Oil Bought the Harding White House and Tried to Steal the Country. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6316-1.

- ↑ MacDonald, Scott B.; Hughes, Jane E. (2007). Separating Fools from Their Money: A History of American Financial Scandals. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction.

- ↑ "McGrain v. Daugherty". Oyez.org. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Teapot Dome scandal. |

- Bates, J. Leonard. The Origins of Teapot Dome. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1963.

- Bennett, Leslie E. "One Lesson From History: Appointment of Special Counsel and the Investigation of the Teapot Dome Scandal". Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1999.

- Ise, John. The United States Oil Policy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1926.

- Murphy, Blakely M. (ed.) Conservation of Oil and Gas: A Legal History. Chicago: Section of Mineral Law, American Bar Association, 1949.

- Noggle, Burl. Teapot Dome: Oil and Politics in the 1920s. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1962.

- Werner, M. R. and Starr, John. Teapot Dome. New York: Viking Press, 1959.

Coordinates: 43°17′19″N 106°10′24″W / 43.2885808°N 106.1733516°W