Tau protein

Tau proteins (or τ proteins, after the Greek letter with that name) are proteins that stabilize microtubules. They are abundant in neurons of the central nervous system and are less common elsewhere, but are also expressed at very low levels in CNS astrocytes and oligodendrocytes.[5] Pathologies and dementias of the nervous system such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease [6] are associated with tau proteins that have become defective and no longer stabilize microtubules properly.

The tau proteins are the product of alternative splicing from a single gene that in humans is designated MAPT (microtubule-associated protein tau) and is located on chromosome 17.[7][8]

The tau proteins were identified in 1975 as heat stable proteins essential for microtubule assembly [9][10] and has since been characterized as an intrinsically disordered protein.[11]

Function

Tau protein is a highly soluble microtubule-associated protein (MAP). In humans, these proteins are found mostly in neurons compared to non-neuronal cells. One of tau's main functions is to modulate the stability of axonal microtubules. Other nervous system MAPs may perform similar functions, as suggested by tau knockout mice that did not show abnormalities in brain development - possibly because of compensation in tau deficiency by other MAPs.[12] Tau is not present in dendrites and is active primarily in the distal portions of axons where it provides microtubule stabilization but also flexibility as needed. This contrasts with MAP6 (STOP) proteins in the proximal portions of axons, which, in essence, lock down the microtubules and MAP2 that stabilizes microtubules in dendrites.

Tau proteins interact with tubulin to stabilize microtubules and promote tubulin assembly into microtubules.[10] Tau has two ways of controlling microtubule stability: isoforms and phosphorylation.

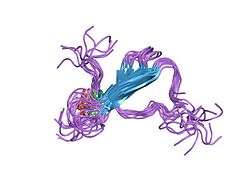

Structure

Six tau isoforms exist in human brain tissue, and they are distinguished by their number of binding domains. Three isoforms have three binding domains and the other three have four binding domains. The binding domains are located in the carboxy-terminus of the protein and are positively charged (allowing it to bind to the negatively charged microtubule). The isoforms with four binding domains are better at stabilizing microtubules than those with three binding domains. The isoforms are a result of alternative splicing in exons 2, 3, and 10 of the tau gene.

Tau is a phosphoprotein with 79 potential Serine (Ser) and Threonine (Thr) phosphorylation sites on the longest tau isoform. Phosphorylation has been reported on approximately 30 of these sites in normal tau proteins.[13]

Phosphorylation of tau is regulated by a host of kinases, including PKN, a serine/threonine kinase. When PKN is activated, it phosphorylates tau, resulting in disruption of microtubule organization.[14]

Phosphorylation of tau is also developmentally regulated. For example, fetal tau is more highly phosphorylated in the embryonic CNS than adult tau.[15] The degree of phosphorylation in all six isoforms decreases with age due to the activation of phosphatases.[16] Like kinases, phosphatases too play a role in regulating the phosphorylation of tau. For example, PP2A and PP2B are both present in human brain tissue and have the ability to dephosphorylate Ser396.[17] The binding of these phosphatases to tau affects tau's association with MTs.

Genetics

In humans, the MAPT gene for encoding tau protein is located on chromosome 17q21, containing 16 exons. The major tau protein in the human brain is encoded by 11 exons. Exons 2, 3 and 10 are alternatively spliced, allowing six combinations (2–3–10–; 2+3–10–; 2+3+10–; 2–3–10+; 2+3–10+; 2+3+10+). Thus, in the human brain, the tau proteins constitute a family of six isoforms with the range from 352-441 amino acids. They differ in either zero, one, or two inserts of 29 amino acids at the N-terminal part (exon 2 and 3), and three or four repeat-regions at the C-terminal part (exon 10). So, the longest isoform in the CNS has four repeats (R1, R2, R3 and R4) and two inserts (441 amino acids total), while the shortest isoform has three repeats (R1, R3 and R4) and no insert (352 amino acids total).

The MAPT gene has two haplogroups, H1 and H2, in which the gene appears in inverted orientations. Haplogroup H2 is common only in Europe and in people with European ancestry. Haplogroup H1 appears to be associated with increased probability of certain dementias, such as Alzheimer's disease. The presence of both haplogroups in Europe means that recombination between inverted haplotypes can result in the lack of one of the functioning copy of the gene, resulting in congenital defects.[18][19][20][21]

Clinical significance

Hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein (tau inclusions, pTau) can result in the self-assembly of tangles of paired helical filaments and straight filaments, which are involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia, and other tauopathies.[22]

All of the six tau isoforms are present in an often hyperphosphorylated state in paired helical filaments from Alzheimer's disease brain. In other neurodegenerative diseases, the deposition of aggregates enriched in certain tau isoforms has been reported. When misfolded, this otherwise very soluble protein can form extremely insoluble aggregates that contribute to a number of neurodegenerative diseases.

Recent research suggests that tau may be released extracellularly by an exosome-based mechanism in Alzheimer's disease.[23][24]

Gender-specific tau gene expression across different regions of the human brain has recently been implicated in gender differences in the manifestations and risk for tauopathies. [25]

Some aspects of how the disease functions also suggest that it has some similarities to prion proteins.[26]

Traumatic brain injury

Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) is now recognized as a central component of brain injury in contact sports, especially American football,[27][28] and the concussive force of military blasts.[29] It can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) that is characterized by fibrillar tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau.[30]

High levels of tau protein in fluid bathing the brain are linked to poor recovery after head trauma.[31]

Tau hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease

The tau hypothesis states that excessive or abnormal phosphorylation of tau results in the transformation of normal adult tau into PHF-tau (paired helical filament) and NFTs (neurofibrillary tangles). Tau protein is a highly soluble microtubule-associated protein (MAP).[10] Through its isoforms and phosphorylation tau protein interacts with tubulin to stabilize microtubule assembly. Tau proteins constitute a family of six isoforms with the range from 352-441 amino acids. The longest isoform in the CNS has four repeats (R1, R2, R3, and R4) and two inserts (441 amino acids total), whereas the shortest isoform has three repeats (R1, R3, and R4) and no insert (352 amino acids total). All of the six tau isoforms are present in an often hyperphosphorylated state in paired helical filaments from AD.

Mutations that alter function and isoform expression of tau lead to hyperphosphorylation. The process of tau aggregation in the absence of mutations is not known but might result from increased phosphorylation, protease action or exposure to polyanions, such as glycosaminoglycans.[6] Hyperphosphorylated tau disassembles microtubules and sequesters normal tau, MAP 1(microtubule associated protein1), MAP 2, and ubiquitin into tangles of PHFs. This insoluble structure damages cytoplasmic functions and interferes with axonal transport, which can lead to cell death.[32]

Interactions

Tau protein has been shown to interact with proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase:

See also

- Tauopathy, a class of diseases associated with accumulated tau proteins

- Dementia pugilistica

- Alzheimer's disease

- Corticobasal degeneration

- Progressive supranuclear palsy

- Proteopathy

- Pick's disease

- Frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17

- Prion

References

- 1 2 3 ENSG00000276155, ENSG00000277956 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000186868, ENSG00000276155, ENSG00000277956 - Ensembl, May 2017

- 1 2 3 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000018411 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ↑ "Human PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ "Mouse PubMed Reference:".

- ↑ Shin RW, Iwaki T, Kitamoto T, Tateishi J (May 1991). "Hydrated autoclave pretreatment enhances tau immunoreactivity in formalin-fixed normal and Alzheimer's disease brain tissues". Lab. Invest. 64 (5): 693–702. PMID 1903170.

- ↑ Lei P, Ayton S, Finkelstein DI, Adlard PA, Masters CL, Bush AI (November 2010). "Tau protein: relevance to Parkinson's disease". Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 42 (11): 1775–1778. PMID 20678581. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2010.07.016.

- ↑ Goedert M, Wischik CM, Crowther RA, Walker JE, Klug A (June 1988). "Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (11): 4051–5. PMC 280359

. PMID 3131773. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.11.4051.

. PMID 3131773. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.11.4051. - ↑ Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA (October 1989). "Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease". Neuron. 3 (4): 519–26. PMID 2484340. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9.

- ↑ Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW (May 1975). "A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 72 (5): 1858–62. PMC 432646

. PMID 1057175. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.5.1858.

. PMID 1057175. doi:10.1073/pnas.72.5.1858. - 1 2 3 Cleveland DW, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW (October 1977). "Purification of tau, a microtubule-associated protein that induces assembly of microtubules from purified tubulin". Journal of Molecular Biology. 116 (2): 207–225. PMID 599557. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(77)90213-3.

- ↑ Cleveland DW, Hwo SY, Kirschner MW (October 1977). "Physical and chemical properties of purified tau factor and the role of tau in microtubule assembly". Journal of Molecular Biology. 116 (2): 227–247. PMID 146092. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(77)90214-5.

- ↑ Harada A, Oguchi K, Okabe S, Kuno J, Terada S, Ohshima T, Sato-Yoshitake R, Takei Y, Noda T, Hirokawa N (June 1994). "Altered microtubule organization in small-calibre axons of mice lacking tau protein". Nature. 369 (6480): 488–91. PMID 8202139. doi:10.1038/369488a0.

- ↑ Billingsley ML, Kincaid RL (May 1997). "Regulated phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of tau protein: effects on microtubule interaction, intracellular trafficking and neurodegeneration". Biochem. J. 323 (3): 577–91. PMC 1218358

. PMID 9169588.

. PMID 9169588. - ↑ Taniguchi T, Kawamata T, Mukai H, Hasegawa H, Isagawa T, Yasuda M, Hashimoto T, Terashima A, Nakai M, Mori H, Ono Y, Tanaka C (March 2001). "Phosphorylation of tau is regulated by PKN". J. Biol. Chem. 276 (13): 10025–31. PMID 11104762. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007427200.

- ↑ Kanemaru K, Takio K, Miura R, Titani K, Ihara Y (May 1992). "Fetal-type phosphorylation of the tau in paired helical filaments". J. Neurochem. 58 (5): 1667–75. PMID 1560225. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb10039.x.

- ↑ Mawal-Dewan M, Henley J, Van de Voorde A, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (December 1994). "The phosphorylation state of tau in the developing rat brain is regulated by phosphoprotein phosphatases". J. Biol. Chem. 269 (49): 30981–7. PMID 7983034.

- ↑ Matsuo ES, Shin RW, Billingsley ML, Van deVoorde A, O'Connor M, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM (October 1994). "Biopsy-derived adult human brain tau is phosphorylated at many of the same sites as Alzheimer's disease paired helical filament tau". Neuron. 13 (4): 989–1002. PMID 7946342. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(94)90264-X.

- ↑ Shaw-Smith C, Pittman AM, Willatt L, Martin H, Rickman L, Gribble S, Curley R, Cumming S, Dunn C, Kalaitzopoulos D, Porter K, Prigmore E, Krepischi-Santos AC, Varela MC, Koiffmann CP, Lees AJ, Rosenberg C, Firth HV, de Silva R, Carter NP (September 2006). "Microdeletion encompassing MAPT at chromosome 17q21.3 is associated with developmental delay and learning disability". Nat. Genet. 38 (9): 1032–7. PMID 16906163. doi:10.1038/ng1858.

- ↑ Zody MC, Jiang Z, Fung HC, Antonacci F, Hillier LW, Cardone MF, Graves TA, Kidd JM, Cheng Z, Abouelleil A, Chen L, Wallis J, Glasscock J, Wilson RK, Reily AD, Duckworth J, Ventura M, Hardy J, Warren WC, Eichler EE (September 2008). "Evolutionary toggling of the MAPT 17q21.31 inversion region". Nat. Genet. 40 (9): 1076–83. PMC 2684794

. PMID 19165922. doi:10.1038/ng.193.

. PMID 19165922. doi:10.1038/ng.193. - ↑ Almos PZ, Horváth S, Czibula A, Raskó I, Sipos B, Bihari P, Béres J, Juhász A, Janka Z, Kálmán J (November 2008). "H1 tau haplotype-related genomic variation at 17q21.3 as an Asian heritage of the European Gypsy population". Heredity (Edinb). 101 (5): 416–9. PMID 18648385. doi:10.1038/hdy.2008.70.

- ↑ Hardy J, Pittman A, Myers A, Gwinn-Hardy K, Fung HC, de Silva R, Hutton M, Duckworth J (August 2005). "Evidence suggesting that Homo neanderthalensis contributed the H2 MAPT haplotype to Homo sapiens". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33 (Pt 4): 582–5. PMID 16042549. doi:10.1042/BST0330582.

- ↑ Alonso A, Zaidi T, Novak M, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K (June 2001). "Hyperphosphorylation induces self-assembly of tau into tangles of paired helical filaments/straight filaments". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (12): 6923–8. PMC 34454

. PMID 11381127. doi:10.1073/pnas.121119298.

. PMID 11381127. doi:10.1073/pnas.121119298. - ↑ Hall, G.F. (2011) Tau misprocessing leads to non-classical tau secretion via vesicle release – implications for the spreading of tau lesions in AD Int Conf. Alz Dis. meeting Paris, France

- ↑ Saman, S. and Hall, G. F. (2011) Tau secretion from M1C human neuroblastoma cells occurs via the release of exosomes. Keystone Meeting on Neurodegenerative diseases, Feb 2011, Taos NM

- ↑ Koeglsberger S, Cordero-Maldonado ML, Antony P, Forster JI, Garcia P, Buttini M, Crawford A, Glaab E (November 2016). "Gender-Specific Expression of Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 9 Modulates Tau Expression and Phosphorylation: Possible Implications for Tauopathies". Molecular Neurobiology. in press: 1–15. PMID 27878758. doi:10.1007/s12035-016-0299-z.

- ↑ Hall GF, Patuto BA (July 2012). "Is tau ready for admission to the prion club?". Prion. 6 (3): 223–33. PMC 3399531

. PMID 22561167. doi:10.4161/pri.19912.

. PMID 22561167. doi:10.4161/pri.19912. - ↑ "Brain Trauma". NOVA. PBS Online by WGBH.

- ↑ Omalu, Bennet I. (July 1, 2005). "Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in a National Football League Player" (PDF). Neurosurgery. 57: 128–134. PMID 15987548. doi:10.1227/01.NEU.0000163407.92769.ED.

- ↑ Goldstein LE, Fisher AM, Tagge CA, Zhang XL, Velisek L, Sullivan JA, et al. (May 2012). "Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in blast-exposed military veterans and a blast neurotrauma mouse model". Science Translational Medicine. 4 (134): 134ra60. PMC 3739428

. PMID 22593173. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003716.

. PMID 22593173. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3003716. - ↑ McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, Stein TD, Alvarez VE, Daneshvar DH, et al. (January 2013). "The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy". Brain. 136 (Pt 1): 43–64. PMC 3624697

. PMID 23208308. doi:10.1093/brain/aws307.

. PMID 23208308. doi:10.1093/brain/aws307. - ↑ Magnoni S, Esparza TJ, Conte V, Carbonara M, Carrabba G, Holtzman DM, Zipfel GJ, Stocchetti N, Brody DL (April 2012) [first published online November 24, 2011]. "Tau elevations in the brain extracellular space correlate with reduced amyloid-β levels and predict adverse clinical outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury". Brain. 135 (Pt 4): 1268–80. PMC 3326246

. PMID 22116192. doi:10.1093/brain/awr286. Lay summary – Washington University in St. Louis.

. PMID 22116192. doi:10.1093/brain/awr286. Lay summary – Washington University in St. Louis. - ↑ Mudher M, Lovestone S (2002). "Alzheimer's disease- do tauists and Baptists finally shake hands?". Trends Neuroscience. 25: 22–6. PMID 11801334. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02031-2.

- ↑ Jensen PH, Hager H, Nielsen MS, Hojrup P, Gliemann J, Jakes R (September 1999). "alpha-synuclein binds to Tau and stimulates the protein kinase A-catalyzed tau phosphorylation of serine residues 262 and 356". J. Biol. Chem. 274 (36): 25481–9. PMID 10464279. doi:10.1074/jbc.274.36.25481.

- ↑ Giasson BI, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ (2003). "Interactions of amyloidogenic proteins". Neuromolecular Med. 4 (1-2): 49–58. PMID 14528052. doi:10.1385/NMM:4:1-2:49.

- ↑ Klein C, Kramer EM, Cardine AM, Schraven B, Brandt R, Trotter J (February 2002). "Process outgrowth of oligodendrocytes is promoted by interaction of fyn kinase with the cytoskeletal protein tau". J. Neurosci. 22 (3): 698–707. PMID 11826099.

- ↑ Yu WH, Fraser PE (April 2001). "S100beta interaction with tau is promoted by zinc and inhibited by hyperphosphorylation in Alzheimer's disease". J. Neurosci. 21 (7): 2240–6. PMID 11264299.

- ↑ Baudier J, Cole RD (April 1988). "Interactions between the microtubule-associated tau proteins and S100b regulate tau phosphorylation by the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II". J. Biol. Chem. 263 (12): 5876–83. PMID 2833519.

- ↑ Hashiguchi M, Sobue K, Paudel HK (August 2000). "14-3-3zeta is an effector of tau protein phosphorylation". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (33): 25247–54. PMID 10840038. doi:10.1074/jbc.M003738200.

Further reading

- Goedert M, Crowther RA, Garner CC (1991). "Molecular characterization of microtubule-associated proteins tau and MAP2". Trends Neurosci. 14 (5): 193–9. PMID 1713721. doi:10.1016/0166-2236(91)90105-4.

- Morishima-Kawashima M, Hasegawa M, Takio K, Suzuki M, Yoshida H, Watanabe A, Titani K, Ihara Y (1995). "Hyperphosphorylation of tau in PHF". Neurobiol. Aging. 16 (3): 365–71; discussion 371–80. PMID 7566346. doi:10.1016/0197-4580(95)00027-C.

- Heutink P (2000). "Untangling tau-related dementia". Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 (6): 979–86. PMID 10767321. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.6.979.

- Goedert M, Spillantini MG (2000). "Tau mutations in frontotemporal dementia FTDP-17 and their relevance for Alzheimer's disease". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1502 (1): 110–21. PMID 10899436. doi:10.1016/S0925-4439(00)00037-5.

- Morishima-Kawashima M, Ihara Y (2001). "[Recent advances in Alzheimer's disease]". Seikagaku. 73 (11): 1297–307. PMID 11831025.

- Blennow K, Vanmechelen E, Hampel H (2002). "CSF total tau, Abeta42 and phosphorylated tau protein as biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease". Mol. Neurobiol. 24 (1-3): 87–97. PMID 11831556. doi:10.1385/MN:24:1-3:087.

- Ingram EM, Spillantini MG (2002). "Tau gene mutations: dissecting the pathogenesis of FTDP-17". Trends Mol Med. 8 (12): 555–62. PMID 12470988. doi:10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02440-1.

- Pickering-Brown S (2004). "The tau gene locus and frontotemporal dementia". Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 17 (4): 258–60. PMID 15178931. doi:10.1159/000077149.

- van Swieten JC, Rosso SM, van Herpen E, Kamphorst W, Ravid R, Heutink P (2004). "Phenotypic variation in frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17". Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 17 (4): 261–4. PMID 15178932. doi:10.1159/000077150.

- Kowalska A, Jamrozik Z, Kwieciński H (2004). "Progressive supranuclear palsy--parkinsonian disorder with tau pathology". Folia Neuropathol. 42 (2): 119–23. PMID 15266787.

- Rademakers R, Cruts M, van Broeckhoven C (2004). "The role of tau (MAPT) in frontotemporal dementia and related tauopathies". Hum. Mutat. 24 (4): 277–95. PMID 15365985. doi:10.1002/humu.20086.

- Lee HG, Perry G, Moreira PI, Garrett MR, Liu Q, Zhu X, Takeda A, Nunomura A, Smith MA (2005). "Tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer's disease: pathogen or protector?". Trends Mol Med. 11 (4): 164–9. PMID 15823754. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2005.02.008.

- Hardy J, Pittman A, Myers A, Gwinn-Hardy K, Fung HC, de Silva R, Hutton M, Duckworth J (2005). "Evidence suggesting that Homo neanderthalensis contributed the H2 MAPT haplotype to Homo sapiens". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33 (Pt 4): 582–5. PMID 16042549. doi:10.1042/BST0330582.

- Deutsch SI, Rosse RB, Lakshman RM (2006). "Dysregulation of tau phosphorylation is a hypothesized point of convergence in the pathogenesis of alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal dementia and schizophrenia with therapeutic implications". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 30 (8): 1369–80. PMID 16793187. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.04.007.

- Williams DR (2006). "Tauopathies: classification and clinical update on neurodegenerative diseases associated with microtubule-associated protein tau". Intern Med J. 36 (10): 652–60. PMID 16958643. doi:10.1111/j.1445-5994.2006.01153.x.

- Pittman AM, Fung HC, de Silva R (2006). "Untangling the tau gene association with neurodegenerative disorders". Hum. Mol. Genet. 15. 15 Spec No 2 (Review Issue 2): R188–95. PMID 16987883. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl190.

- Roder HM, Hutton ML (2007). "Microtubule-associated protein tau as a therapeutic target in neurodegenerative disease". Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 11 (4): 435–42. PMID 17373874. doi:10.1517/14728222.11.4.435.

- van Swieten J, Spillantini MG (2007). "Hereditary frontotemporal dementia caused by Tau gene mutations". Brain Pathol. 17 (1): 63–73. PMID 17493040. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00052.x.

- Caffrey TM, Wade-Martins R (2007). "Functional MAPT haplotypes: bridging the gap between genotype and neuropathology". Neurobiol. Dis. 27 (1): 1–10. PMC 2801069

. PMID 17555970. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.006.

. PMID 17555970. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2007.04.006. - Delacourte A (2005). "Tauopathies: recent insights into old diseases". Folia Neuropathol. 43 (4): 244–57. PMID 16416389.

- Hirokawa N, Shiomura Y, Okabe S (October 1988). "Tau proteins: the molecular structure and mode of binding on microtubules". J. Cell Biol. 107 (4): 1449–59. PMC 2115262

. PMID 3139677. doi:10.1083/jcb.107.4.1449.

. PMID 3139677. doi:10.1083/jcb.107.4.1449.

External links

- tau Proteins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on MAPT-Related Disorders

- MR scans of variant CJD CSF Tau positive man