Tatars

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 6,200,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 5,319,877 | |

| 477,875 | |

| 319,377 | |

| 240,000 | |

| 175,500 | |

| 36,355 | |

| 28,334 | |

| 25,900 | |

| 24,137 | |

| 15,000 | |

| 7,300 | |

| 7,000 | |

| 6,800-7,200 | |

| 5,000 | |

| 2,850 | |

| 1,981 | |

| 1,916 | |

| 1,803 | |

| 900 | |

| Languages | |

| Tatar, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam, Orthodox Christianity | |

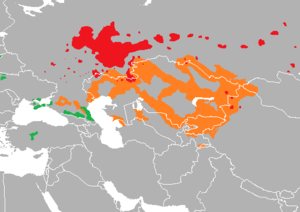

The Tatars (Russian: татары); (Tatar: татарлар) are Turkic-speaking people[1] living in Asia and Europe. The name "Tatar" first appears in written form on the Kul Tigin monument as 𐱃𐱃𐰺 (TaTaR). Historically, the term "Tatars" was applied to a variety of Turco-Mongol semi-nomadic empires who controlled the vast region known as Tartary. More recently, however, the term refers more narrowly to people who speak one of the Turkic[1] languages.

The Mongol Empire, established under Genghis Khan in 1206, allied with the Tatars. Under the leadership of Genghis Khan's grandson Batu Khan (c. 1207–1255), the Mongols moved westwards, driving with them many of the Mongol tribes toward the plains of Russia. The "Tatar" clan still exists among the Mongols and Hazaras.

The largest group by far that the Russians have called "Tatars" are the Volga Tatars, native to the Volga region (Tatarstan and Bashkortostan), who for this reason are often also simply known as "Tatars", with their language known as the Tatar language. As of 2002 they had an estimated population close to 6 million. There is a common belief that Russians and Tatars are closely intermingled, illustrated by the famous saying "scratch any Russian just a little and you will discover a Tatar underneath"[2] and the fact that a number of noble families in pre-Petrine Russia had Tatar origins[3]; however, genetics show that Russians form a cluster with Northern and Eastern Europeans (especially Ukrainians and Poles), and are very far from Turkic people.[4][5]

Name

The name "Tatar" likely originated amongst the nomadic Mongolic Tatar confederation in the north-eastern Gobi desert in the 5th century.[6] The name "Tatar" was first recorded on the Orkhon inscriptions: Kul Tigin (CE 732) and Bilge Khagan (CE 735) monuments as ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() :

:![]()

![]()

![]() :

:![]()

![]()

![]() Otuz Tatar Bodun ('Thirty Tatar' clan)[7] and

Otuz Tatar Bodun ('Thirty Tatar' clan)[7] and ![]()

![]()

![]() :

:![]()

![]()

![]() Tokuz Tatar ('Nine Tatar')[8][9][10][11] referring to the Tatar confederation.

Tokuz Tatar ('Nine Tatar')[8][9][10][11] referring to the Tatar confederation.

"Tatar" became a name for populations of the former Golden Horde in Europe, such as those of the former Kazan, Crimean, Astrakhan, Qasim, and Siberian Khanates. The form "Tartar" has its origins in either Latin or French, coming to Western European languages from Turkish and Persian (tātār, "mounted messenger"). From the beginning, the extra r was present in the Western forms, and according to the Oxford English Dictionary this was most likely due to an association with Tartarus.[12]

The Persian word is first recorded in the 13th century in reference to the hordes of Genghis Khan and is of unknown origin, according to OED "said to be" ultimately from tata, a name of the Mongols for themselves. The Arabic word for Tatars is تتار. Tatars themselves wrote their name as تاتار or طاطار. The Chinese term for Tatars was Dada 韃靼, especially after the end of the Yuan period (14th century), but also recorded as a term for Mongolian-speaking peoples of the northern steppes during the Tang period (8th century).[13] The name "Tatars" was used as an alternative term for the Shiwei, a nomadic confederation to which these Tatar people belonged.

Russians and Europeans used the name Tatar to denote Mongols as well as Turkic peoples under Mongol rule (especially in the Golden Horde). Later, it applied to any Turkic- or Mongolic-speaking people encountered by Russians. Eventually, however, the name became associated with the Turkic Muslims of Ukraine and Russia, namely the descendants of Muslim Volga Bulgars, Kipchaks, Cumans, and Turkicized Mongols or Turko-Mongols (Nogais), as well as other Turkic-speaking peoples (Siberian Tatars, Qasim Tatars, and Mishar Tatars)[14][15][16][17][18] in the territory of the former Russian Empire (and as such generally includes all Northwestern Turkic-speaking peoples).[19]

Nowadays Tatar is usually used to refer to the people, but Tartar is still almost always used for derived terms such as tartar sauce or steak tartare.[20]

All Turkic peoples living within the Russian Empire were named Tatar (as a Russian exonym). Some of these populations still use Tatar as a self-designation, others do not.[21]

- Kipchak groups

- Kipchak–Bulgar branch, or "Tatar" in the narrow sense

- Kipchak–Cuman branch

- Crimean Tatars

- Karachays and Balkars: Mountain Tatars

- Kumyks: Daghestan Tatars

- Kipchak–Nogai branch:

- Siberian branch:

- Siberian Tatars

- Altay people: Altay Tatars, including the Tubalar or Chernevo Tatars[22]

- Chulyms or Chulym Tatars

- Khakas people: Yenisei Tatars (also Abakan Tatars or Achin Tatars), still use the Tatar designation

- Shors: Kuznetsk Tatars

- Oghuz branch

- Azerbaijani people: Caucasus Tatars (also Transcaucasia Tatars or Azerbaijan Tatars)

The name Tatar is also an endonym to a number of peoples of Siberia and Russian Far East, namely the Khakas people.

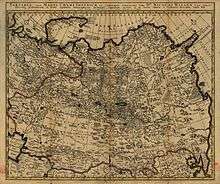

History

As various nomadic groups became part of Genghis Khan's army in the early 13th century, a fusion of Mongol and Turkic elements took place, and the invaders of Rus' and the Pannonian Basin became known to Europeans as Tatars or Tartars (see Tatar yoke).[6] After the breakup of the Mongol Empire, the Tatars became especially identified with the western part of the empire, known as the Golden Horde.[6]

The various Tatar khanates of the early modern period represent the remnants of the breakup of the Golden Horde and of its successor, the Great Horde. These include:

- the Khanate of Kazan (1438), conquered by the Tsardom of Russia in 1552, but continued as a Russian vassal state within the Qasim Khanate (established 1452), until 1681

- the Nogai Horde (1440s), conquered by Russia in 1634

- the Khanate of Crimea (1441), conquered by the Russian Empire in 1783

- the Kazakh Khanate (1456), gradual Russian conquest in the 18th century, but finally absorbed into the Russian Empire only in 1847

- the Khanate of Astrakhan (1466), conquered by Russia in 1556

- the Tyumen Khanate (1468, later Khanate of Sibir), conquered by the Tsardom of Russia in 1598

The Mongol dominance in Central Asia was absolute during the 14th and 15th centuries. The Crimean-Nogai raids into Russia aimed especially at the capture of slaves, most of whom were exported to the Ottoman Empire. The raids were an important drain of the human and economic resources of both countries. They largely prevented the settlement of the "Wild Fields" – the steppe and forest-steppe land that extends from a hundred or so miles south of Moscow to the Black Sea. The raids were also important in the development of the Cossacks.

The end of absolute Tatar dominance came in the late 15th century, heralded by the Great stand on the Ugra river in 1480. During the 16th through 18th centuries, the gradual expansion of Russia led to the absorption of the Tatar khanates into Russian territory. The Crimean Tatars attacked Russia in 1507, followed by two centuries of Russo-Crimean Wars for the Volga basin. Similarly, the Russo-Kazan Wars lasted for the best part of a century and ended with the Russian conquest of the Kazan khanate.

The last of the Tatar khanates, the Kazakhs, remained independent until 1822. Their last ruler, Kenesary Khan, was proclaimed khan of the Kazakhs when the Russian Empire was already fully in control of Kazakhstan; Russian law prohibited the Kazakhs from selecting their leader after 1822. The popular rise of Kenesary Khan was in defiance of Russian control of Kazakhstan, and his time as khan was spent on continuous fighting with the Russian imperial forces until his death in 1847.

Languages

The Tatar language together with the Bashkir language forms the Kypchak-Bolgar (also "Uralo-Caspian") group within the Kypchak languages, also known as Northwestern Turkic.

There are three Tatar dialects: Eastern, Central, Western.[23] The Western dialect (Misher) is spoken mostly by Mishärs, the Central dialect is spoken by Kazan and Astrakhan Tatars, and the Eastern (Sibir) dialect is spoken by Siberian Tatars in western Siberia. All three dialects have subdialects. Central Tatar is the base of literary Tatar.

These Siberian Tatar dialects are independent of Volga–Ural Tatar. The dialects are quite remote from Standard Tatar and from each other, often preventing mutual comprehension. The claim that this language is part of the modern Tatar language is typically supported by linguists in Kazan and denounced by Siberian Tatars.

Crimean Tatar[24] is the indigenous language of the Crimean Tatar peoples. Because of its common name, Crimean Tatar is sometimes mistaken to be a dialect of Kazan Tatar. Although these languages are related (as both are Turkic), the Kypchak languages closest to Crimean Tatar are (as mentioned above) Kumyk and Karachay-Balkar, not Kazan Tatar.

Contemporary groups

The majority of the Tatar population are Volga Tatars, native to the Volga region, and the Crimean Tatars of Crimea. There are smaller groups of Lipka Tatars and Astrakhan Tatars in Europe and the Siberian Tatars in Asia.

Volga Tatars

The present territory of Tatarstan was inhabited by the Volga Bulgars, who settled on the Volga river in the 7th century AD and converted to Islam in 922 during the missionary work of Ahmad ibn Fadlan. After the Mongol invasion, Volga Bulgaria was annexed by the Golden Horde. Most of the population survived, and there may have been a certain degree of mixing between it and the Kipchaks of the Horde during the ensuing period. The group as a whole accepted the exonym "Tatars" (finally in the end of the 19th century; although the name Bulgars persisted in some places; the majority identified themselves simply as the Muslims) and the language of the Kipchaks; on the other hand, the invaders eventually converted to Islam. As the Horde disintegrated in the 15th century, the area became the territory of the Kazan khanate, which was ultimately conquered by Russia in the 16th century.

Some Volga Tatars speak different dialects of Tatar language. Therefore, they form distinct groups such as the Mişär group and the Qasim group. Mişär-Tatars (or Mishars) are a group of Tatars speaking a dialect of the Tatar language. They live in Chelyabinsk, Tambov, Penza, Ryazan, Nizhegorodskaya oblasts of Russia and in Bashkortostan and Mordovia. They lived near and along the Volga River, in Tatarstan. The Western Tatars have their capital in the town of Qasím (Kasimov in Russian transcription) in Ryazan Oblast, with a Tatar population of 1100. A minority of Christianized Volga Tatars are known as Keräşens.

The Volga Tatars used the Turkic Old Tatar language for their literature between the 15th and 19th centuries. It was written in the İske imlâ variant of the Arabic script, but actual spelling varied regionally. The older literary language included a large number of Arabic and Persian loanwords. The modern literary language, however, often uses Russian and other European-derived words instead.

Outside of Tatarstan, urban Tatars usually speak Russian as their first language (in cities such as Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, Nizhniy Novgorod, Tashkent, Almaty, and cities of the Ural and western Siberia) and other languages in a worldwide diaspora.

In the 1910s the Volga Tatars numbered about half a million in the Kazan Governorate in Tatarstan, their historical homeland, about 400,000 in each of the governments of Ufa, 100,000 in Samara and Simbirsk, and about 30,000 in Vyatka, Saratov, Tambov, Penza, Nizhny Novgorod, Perm and Orenburg. An additional 15,000 had migrated to Ryazan or were settled as prisoners in the 16th and 17th centuries in Lithuania (Vilnius, Grodno and Podolia). An additional 2000 resided in St. Petersburg.

Most Kazan Tatars practice Sunni Islam. The Kazan Tatars speak the Tatar language, a Turkic language with a substantial amount of Russian and Arabic loanwords.

Before 1917, polygamy was practiced only by the wealthier classes and was a waning institution.

There is an ethnic nationalist movement among Kazan Tatars that stresses descent from the Bulgars and is known as Bulgarism – there have been graffiti on the walls in the streets of Kazan with phrases such as "Bulgaria is alive" (Булгария жива)

A significant number of Volga Tatars emigrated during the Russian Civil War, mostly to Turkey and Harbin, China. According to the Chinese government, there are still 5,100 Tatars living in Xinjiang province.

Crimean Tatars

The number of Crimean Tatars is estimated at 650,000. The Crimean Tatars emerged as a nation at the time of the Crimean Khanate. The Crimean Khanate was a Turkic-speaking Muslim state that was among the strongest powers in Eastern Europe until the beginning of the 18th century.[25]

The nobles and rulers of the Crimean Tatars were the descendants of Hacı I Giray, a Jochid descendant of Genghis Khan, and of Batu Khan of the Mongol Golden Horde. The Crimean Tatars mostly adopted Islam in the 14th century and thereafter Crimea became one of the centers of Islamic civilization. The Khanate was officially a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire with great autonomy after 1448. The Russo-Turkish War (1768–74) resulted in the defeat of the Ottomans by the Russians, and according to the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) signed after the war, Crimea became independent and Ottomans renounced their political right to protect the Crimean Khanate. After a period of political unrest in Crimea, Russia violated the treaty and annexed the Crimean Khanate in 1783.

The Crimean Tatars are subdivided into three sub-ethnic groups: the Tats (not to be confused with Tat people, living in the Caucasus region) who used to inhabit the mountainous Crimea before 1944 (about 55%), the Yalıboyu who lived on the southern coast of the peninsula (about 30%), and the Noğay (about 15%).

Crimean Tatars in Romania and Bulgaria

Crimean Tatars have been present on the territory of today's Romania and Bulgaria since the 13th century. In Romania, according to the 2002 census, 24,000 people declared their ethnicity as Tatar, most of them being Crimean Tatars living in Constanța County in the region of Dobruja. The Crimean Tatars were colonized there by the Ottoman Empire beginning in the 17th century.

Lipka Tatars

The Lipka Tatars are a group of Turkic-speaking Tatars who originally settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania at the beginning of the 14th century. The first settlers tried to preserve their shamanistic religion and sought asylum amongst the non-Christian Lithuanians.[26] Towards the end of the 14th century, another wave of Tatars—Muslims, this time—were invited into the Grand Duchy by Vytautas the Great. These Tatars first settled in Lithuania proper around Vilnius, Trakai, Hrodna and Kaunas[26] and later spread to other parts of the Grand Duchy that later became part of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. These areas comprise present-day Lithuania, Belarus and Poland. From the very beginning of their settlement in Lithuania they were known as the Lipka Tatars.

From the 13th to 17th centuries various groups of Tatars settled and/or found refuge within the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth. This was promoted especially by the Grand Dukes of Lithuania because of their reputation as skilled warriors. The Tatar settlers were all granted szlachta (nobility) status, a tradition that was preserved until the end of the Commonwealth in the 18th century. They included the Lipka Tatars (13th–14th centuries) as well as Crimean and Nogay Tatars (15th–16th centuries), all of which were notable in Polish military history, as well as Volga Tatars (16th–17th centuries). They all mostly settled in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Various estimates of the number of Tatars in the Commonwealth in the 17th century are about 15,000 persons and 60 villages with mosques. Numerous royal privileges, as well as internal autonomy granted by the monarchs, allowed the Tatars to preserve their religion, traditions, and culture over the centuries. The Tatars were allowed to intermarry with Christians, which was uncommon in Europe at the time. The May Constitution of 1791 gave the Tatars representation in the Polish Sejm.

Although by the 18th century the Tatars adopted the local language, the Islamic religion and many Tatar traditions (e.g. the sacrifice of bulls in their mosques during the main religious festivals) were preserved. This led to formation of a distinctive Muslim culture, in which the elements of Muslim orthodoxy mixed with religious tolerance formed a relatively liberal society. For instance, the women in Lipka Tatar society traditionally had the same rights and status as men, and could attend non-segregated schools.

About 5,500 Tatars lived within the inter-war boundaries of Poland (1920–1939), and a Tatar cavalry unit had fought for the country's independence. The Tatars had preserved their cultural identity and sustained a number of Tatar organisations, including a Tatar archives and a museum in (Vilnius).

The Tatars suffered serious losses during World War II and furthermore, after the border change in 1945, a large part of them found themselves in the Soviet Union. It is estimated that about 3000 Tatars live in present-day Poland, of which about 500 declared Tatar (rather than Polish) nationality in the 2002 census. There are two Tatar villages (Bohoniki and Kruszyniany) in the north-east of present-day Poland, as well as urban Tatar communities in Warsaw, Gdańsk, Białystok, and Gorzów Wielkopolski. Tatars in Poland sometimes have a Muslim surname with a Polish ending: Ryzwanowicz; another surname sometimes adopted by more assimilated Tatars is Tatara or Tataranowicz or Taterczyński, which literally mean "son of a Tatar".

The Tatars were relatively noticeable in the Commonwealth military as well as in Polish and Lithuanian political and intellectual life for such a small community. In modern-day Poland, their presence is also widely known, due in part to their noticeable role in the historical novels of Henryk Sienkiewicz, which are universally recognized in Poland. A number of Polish intellectual figures have also been Tatars, e.g. the prominent historian Jerzy Łojek.

A small community of Polish-speaking Tatars settled in Brooklyn, New York City, in the early 20th century. They established a mosque that is still in use today.

Astrakhan Tatars

The Astrakhan Tatars (around 80,000) are a group of Tatars, descendants of the Astrakhan Khanate's nomadic population, who live mostly in Astrakhan Oblast. For the Russian census in 2010, most Astrakhan Tatars declared themselves simply as Tatars and few declared themselves as Astrakhan Tatars. A large number of Volga Tatars live in Astrakhan Oblast and differences between them have been disappearing.

Siberian Tatars

The Siberian Tatars occupy three distinct regions—a strip running west to east from Tobolsk to Tomsk—the Altay and its spurs—and South Yeniseisk. They originated in the agglomerations of various indigenous North Asian stems that, in the region north of the Altay, reached some degree of culture between the 4th and 5th centuries, but were subdued and enslaved by the Mongols. The 2010 census recorded 6,779 Siberian Tatars in Russia. According to the 2002 census there are 500,000 Tatars in Siberia, but 400,000 of them are Volga Tatars who settled in Siberia during periods of colonization.[27]

Genetics

According to over 100 samples from the Tatarstan DNA project, the most common Y-DNA haplogroup of the ethnic Volga Tatars is Haplogroup R1a (over 20%), predominantly from the Asian R1a-Z93 subclade.[28] Haplogroup N is the other significant haplogroup. According to different data J2a or J2b may be the more common subclade of Haplogroup J2 in Volga Tatars. The haplogroups C and Q are among the rare haplogroups.

Haplogroups of 450 Tatars, summarized from the studies Rootsi 2007, Tambets 2004, Balanovsky in prep., Wells 2001[29]

- N1c2: 21,0%

- R1a: 19,0%

- I1: 13,2%

- N1c1: 13,0%

- J2: 8,1%

- R1b1b2: 6,0%

- E1b1a: 4,0%

- O: 3,0%

- I2a1: 2,8%

- C: 2,7%

- I2a2: 1,8%

- G: 1,0%

- J1: 1,0%

- L: 1,0%

- Q: 1,0%

- T: 1,0%

Haplogroups in Volga Tatars(122 samples):[30]

- C2: 2%

- E: 4% (V13: 3%)

- G2a: 2%

- I1: 6%

- I2a1: 5%

- I2a2: 2%

- J2a: 7%

- J2b: 2%

- L1: 2%

- N1c2: 9%

- N1c1: 16%

- O3: 2%

- Q1: 2%

- R1a: 33% (Z282: 19%, Z93: 14%)

Haplogroups in Crimean Tatars(22 samples):[31]

- R-M17: 32%

- R-M173: 9%

- O-M175: 5%

- O-M122: 5%

- J-M172: 14%

- I-M170: 5%

- F-M89: 18%

- C-M130: 9%

- E-M96: 5%

According to Mylyarchuk et al. "It was found that mitochondrial gene pool of the Volga Tatars consists of two parts, but western Eurasian component prevails considerably (84% on average) over eastern Asian one (16%)." among 197 Kazan Tatars and Mishans.[32]

The study of Suslova et al found indications of two non-Kipchak sources of admixture, Finno-Ugric and Bulgar: "Together with Tatars, Russians have high frequencies of allele families and haplotypes characteristic of Finno-Ugric populations. This presupposes a Finno-Ugric impact on Russian and Tatar ethnogenesis.... Some aspects of HLA in Tatars appeared close to Chuvashes and Bulgarians, thus supporting the view that Tatars may be descendents of ancient Bulgars."[33]

Gallery

Flags

Flag of Nogai Khanate

Flag of Nogai Khanate Flag of the Crimean Tatars

Flag of the Crimean Tatars Flag of Tatarstan

Flag of Tatarstan Flag of the Kazan Khanate

Flag of the Kazan Khanate Golden Horde flag

Golden Horde flag

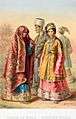

Pictures

- Tatars in Kazan, 1871

Mintimer Shaimiyev (left), the president of the republic of Tatarstan, in the Qolşärif Mosque, Kazan, with Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow (right)

Mintimer Shaimiyev (left), the president of the republic of Tatarstan, in the Qolşärif Mosque, Kazan, with Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow (right) Siberian Tatars

Siberian Tatars_pg261_TATARS_OF_THE_CRIMEA.jpg) Crimean Tatars, 1891

Crimean Tatars, 1891 Crimean Tatar women, early 1900s

Crimean Tatar women, early 1900s

Paintings

Tatar elder and his horse.

Tatar elder and his horse. Tatar in Ottoman service.

Tatar in Ottoman service. Marco polo wearing Tatar outfit

Marco polo wearing Tatar outfit Tatar woman

Tatar woman Tatar woman

Tatar woman Tatar woman

Tatar woman Tatar woman

Tatar woman Tatar shepherd-boy

Tatar shepherd-boy Tatars

Tatars- Lithuanian Tatars of Napoleonic army

Tatar elder

Tatar elder Tatar family

Tatar family- Siberian Tatars

Tatar girl

Tatar girl Tatars' raid on Moscow

Tatars' raid on Moscow Tatar riders

Tatar riders- Recovery of Tatar captives.

Tatar costumes.

Tatar costumes. Tatar rider

Tatar rider Tatar elder inviting guests.

Tatar elder inviting guests. Tatar horsemen

Tatar horsemen Tatars in the vanguard of the Ottoman army

Tatars in the vanguard of the Ottoman army Kazan Tatars 1862

Kazan Tatars 1862

Language

- Quran of the Tatars.

Cover page of Tatar Yana imla book, printed with Separated Tatar language in Arabic script in 1924.

Cover page of Tatar Yana imla book, printed with Separated Tatar language in Arabic script in 1924. A Tatar alphabet book printed in 1778. Arabic script is used, Cyrillic text is in Russian. Хальфин, Сагит. Азбука татарского языка. — М., 1778. — 52 с.

A Tatar alphabet book printed in 1778. Arabic script is used, Cyrillic text is in Russian. Хальфин, Сагит. Азбука татарского языка. — М., 1778. — 52 с.

See also

References

- 1 2 http://global.britannica.com/topic/Tatar

- ↑ Matthias Kappler, Intercultural Aspects in and Around Turkic Literatures: Proceedings of the International Conference Held on October 11th-12th, 2003 in Nicosia, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag (2006), p. 165

- ↑ Thomas Riha, Readings in Russian Civilization, Volume 1: Russia Before Peter the Great, 900-1700, University of Chicago Press (2009), p. 186

- ↑ Mitochondrial DNA sequence diversity in Russians

- ↑ Two Sources of the Russian Patrilineal Heritage in Their Eurasian Context

- 1 2 3 Tatar. (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 28, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://search.eb.com/eb/article-9071375

- ↑ "Kül Tiğin (Gültekin) Yazıtı Tam Metni (Full text of Kul Tigin monument with Turkish transcription)". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ "Bilge Kağan Yazıtı Tam Metni (Full text of Bilge Khagan monument with Turkish transcription)". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ "The Kultegin’s Memorial Complex". Retrieved 5 April 2014.

- ↑ Ross, E. Denison; Vilhelm Thomsen. "The Orkhon Inscriptions: Being a Translation of Professor Vilhelm Thomsen's Final Danish Rendering". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 5 (4, 1930): 861–876. JSTOR 607024.

- ↑ Thomsen, Vilhelm Ludvig Peter (1896). Inscriptions de l'Orkhon déchiffrées. Helsingfors, Impr. de la Société de littérature finnoise. p. 140.

- ↑ citing a letter to St Louis of Frances dated 1270 which makes the connection explicit, "In the present danger of the Tartars either we shall push them back into the Tartarus whence they are come, or they will bring us all into heaven"

- ↑ Chen Dezhi 陳得芝, Jia Jingyan 賈敬顔 (1992). "Dada 達靼", in: Zhongguo da baike quanshu 中國大百科全書, Zhongguo lishi 中國歷史, vol. 1, pp. 132-133. Cited after "Dada 韃靼 Tatars" by Ulrich Theobald, chinaknowledge.de.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica: Tatar, also spelled Tartar, any member of several Turkic-speaking peoples ...

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia: Tatars (tä´tərz) or Tartars (tär´tərz), Turkic-speaking peoples living primarily in Russia, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

- ↑ Meriam-Webster: Tatar – a member of any of a group of Turkic peoples found mainly in the Tatar Republic of Russia and parts of Siberia and central Asia

- ↑ Oxford Dictionaries: Tatar – a member of a Turkic people living in Tatarstan and various other parts of Russia and Ukraine.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa: Turks are an ethnolinguistic group living in a broad geographic expanse extending from southeastern Europe through Anatolia and the Caucasus Mountains and throughout Central Asia. Thus Turks include the Turks of Turkey, the Azeris of Azerbaijan, and the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tatars, Turkmen, and Uzbeks of Central Asia, as well as many smaller groups in Asia speaking Turkic languages.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica: Tatar, also spelled Tartar, any member of several Turkic-speaking peoples ... The Columbia Encyclopedia: Tatars (tä´tərz) or Tartars (tär´tərz), Turkic-speaking peoples living primarily in Russia, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. Meriam-Webster: Tatar – a member of any of a group of Turkic peoples found mainly in the Tatar Republic of Russia and parts of Siberia and central Asia Oxford Dictionaries: Tatar – a member of a Turkic people living in Tatarstan and various other parts of Russia and Ukraine. They are the descendants of the Tartars who ruled central Asia in the 14th century. Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa: Turks are an ethnolinguistic group living in a broad geographic expanse extending from southeastern Europe through Anatolia and the Caucasus Mountains and throughout Central Asia. Thus Turks include the Turks of Turkey, the Azeris of Azerbaijan, and the Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Tatars, Turkmen, and Uzbeks of Central Asia, as well as many smaller groups in Asia speaking Turkic languages.

- ↑ "Tartar, Tatar, n.2 (a.)". (1989). In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 11 September 2008, from Oxford English Dictionary Online.

- ↑ Татары (in Russian). Энциклопедия «Вокруг света». Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ The name originating from the name of Spruce-fir Taiga forests in Russian language: черневая тайга

- ↑ Akhatov G. "Tatar dialectology". Kazan, 1984. (Tatar language)

- ↑ also called Crimean language, Crimean Turkish

- ↑ Halil İnalcik, 1942

- 1 2 (in Lithuanian) Lietuvos totoriai ir jų šventoji knyga – Koranas Archived 2007-10-29 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Siberian Tatars

- ↑ "Family Tree DNA - Tatarstan". www.familytreedna.com.

- ↑ "Балановский О.П., Пшеничнов А.С., Сычев Р.С., Евсеева И.В., Балановская Е.В. Y-base: частоты гаплогрупп Y хромосомы у народов мира, 2010

- ↑ http://pereformat.ru/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/russian-plain-01.jpg

- ↑ http://s017.radikal.ru/i415/1112/bf/0ea62065dd07.jpg

- ↑ Malyarchuk, Boris; Derenko, Miroslava; Denisova, Galina; Kravtsova, Olga (1 October 2010). "Mitogenomic Diversity in Tatars from the Volga-Ural Region of Russia". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 27 (10): 2220–2226. ISSN 0737-4038. PMID 20457583. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq065.

- ↑ Suslova, T. A.; Burmistrova, A. L.; Chernova, M. S.; Khromova, E. B.; Lupar, E. I.; Timofeeva, S. V.; Devald, I. V.; Vavilov, M. N.; Darke, C. (1 October 2012). "HLA gene and haplotype frequencies in Russians, Bashkirs and Tatars, living in the Chelyabinsk Region (Russian South Urals)". International Journal of Immunogenetics. 39 (5): 394–408. ISSN 1744-313X. PMID 22520580. doi:10.1111/j.1744-313X.2012.01117.x.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tatar people. |

-

"Tatars". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

"Tatars". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

.jpg)