Tarashikomi

| Art history |

| Eastern art history |

| Japanese art history |

| General |

|

Japanese Art Main Page |

| Historical Periods |

|

Jōmon and Yayoi periods |

| Japanese Artists |

|

Artists (chronological) |

| Schools, Styles and Movements |

|

Schools category |

| The Art World |

|

Art museums |

| Anime and Manga |

|

Anime -

Manga -

Animators |

| Japan WikiProject |

Tarashikomi (meaning "dripping in") is a Japanese painting technique, in which a second layer of paint is applied before the first layer is dry. This effect creates a dripping form for fine details such as ripples in water or flower petals on a tree. Japanese paintings in the past were usually done on paper (or silk) with watercolors. The paintings in the Tomb of Kyushu are some of the earliest Japanese art, painted on the tomb’s walls between the fifth and seventh centuries AD. Silk and paper came from China, and in the seventh century was used primarily for writing; however, it began to be used for art during the eighth century. Silk was most common for hanging scroll paintings, while paper was used for calligraphy on handscrolls. Nikawa (animal glue) was used for paint; the glue was made from cowhide or other animal skins.[1]

Honami Koētsu

Honami Kōetsu (1558–1637) was inspired by the Heian period, which was a model of art from the distant past. These works were popular among the samurai, who tried to evoke the past without losing the beauty of the Heien period. Masters of different artistic media and schools inspired other artists, who created their own styles of art or schools. Honami inspired Tawaraya Sōtatsu, who is noted for his tarashikomi technique; Tawaraya inspired Ogata Kōrin, who consolidated the Rinpa school with his brother Kenzan. The tarashikomi technique is part of the Rinpa style of decorative arts.

Tawaraya Sōtatsu

Tawaraya and Honami created a new decorative-painting school, which later influenced Ogata Kōrin. Tawaraya made a living by selling his decorated scrolls, screens and fans from his shop (eya),[2] and is known for his tarashikomi paintings on fans and screens. Tawaraya's depth of style is reminiscent of realistic Chinese painting, but freer.[3]

Tawaraya's new style of painting was seen mainly in his paintings on screens; examples of his tarashikomi works are Flowers and Grasses of the Four Seasons and Lotus and Waterfowl. His handscroll entitled Kitano Tenjin engi is known for its tarashikomi rendering of clouds and the puffs surrounding them.[4] Tawaraya's school (1624–1644) painted many folded screens, which were functional as well as beautiful; they could be set up and put away easily, allowing people to enjoy them seasonally, separately or for a special occasion. Themes were common, inspired by tales or poems of other artists. The screens were not meant to remain in a corner, like wall art in modern Western houses. Sometimes a single object was repeated on the screen, causing the images to apparently move across the screens. The screens were arranged to fold in on each other; the motion of folding enhanced the movement of the panels, often giving images more dimension.

Tawaraya's paintings were referred to as the "Tawaraya style". Several of his paintings may be seen on fans and scrolls, the best-known being images from The Tale of Genji. Ogata's paintings also employed this style, but are simpler. Although Tawaraya preceded Ogata, Ogata's new style would come to bear the name of Rinpa (Rin from the end of his first name and pa from the Japanese word for "school"). Of course, there were some differences between Tawaraya Sotatsu's works and Ogata Kōrin's style. The main differences between Tarawaya's style and the new Rinpa style was that the latter used sharper contours and lines and also increased the amount of color used in paintings (especially on screens).[5]

Rinpa school

Rinpa was a style of decorative painting. It was common to add silver or gold leaf to paintings for effect. The metallic look gave the background a sheen, which gave the painted objects on top a layered appearance. In addition, this gave the paintings more solidity so that screens would be less permeable. Japanese artists painted on screens using paint components of different layers. Silk was the usual surface; with its open weave, an artist could paint on both sides of the screen (which made the screen more durable). This durability is what made tarashikomi possible, gives screens (and other artwork) a detailed look. Tarashikomi could add details (such as leaves or flowers on a tree), which made them stand out vibrantly against the background. The dripped paint layers made buds on a tree shine, and moss glow against shadowed bark; not only did it strengthen the screen, it imparted a three-dimensional quality.

Buddhist painters are best known for these techniques; the ukiyo ("floating world") pictures are an example.[6] These pictures were popular among the middle class during the Edo period. Outside the Edo limits, the Floating World became a popular place of escape and pleasure from the strict shogunate. When the water was high, the Floating World existed on raised wooden planks; when the waters receded, the people gathered on the banks. Carefree activity was found there, providing interesting material for artists. Working people could escape, for a time, their everyday world. With no family or obligations, one could relax.[7]

Ogata Kōrin

Tarashikomi was enhanced by Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716). Ogata’s original name was Ichinojo Koretomi; he changed it to escape from debt. He had four children with different women, and was known for frivolity; however, Ogata became one of Japan’s master Rimpa painters. Some of his early works were paintings on fans which he made for the Empress dowager. After 1709, Ogata began dedicating himself to the Rimpa style. He made many screen paintings, such as Irises (from The Tales of Ise). Irises is based on the part of the tale when a traveler composes a poem after seeing a pond with beautiful Japanese irises (although Ogata omits the poet, bridge, and pond). The flowers are used in six screens.

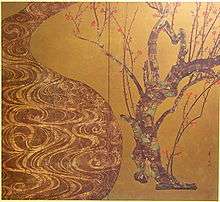

Another example of Ogata's tarashikomi screens is Hakurakuten, which demonstrates Tawaraya’s influence. The pool of water in which the bridge sits is colored by using a second pigment of color, added while the first coating of paint was still wet. Ogata’s best-known screen was Red and White Plum Blossoms (1712–1713). This was a pair of screens with two trees, attractive separately but beautiful when unified. The silver stream swirls between the two trees on a golden background. Points of red and white color highlight the leaves and fruit on the plum trees; they break up the colors by allowing them to bleed while partially wet. The twigs, stalks and tree trunks are detailed by the tarashikomi technique. The imagery looks random, but is not (characteristic of the Rimpa school). Another Rimpa master who used the tarashikomi technique was Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828). His scroll, Night View of the Arched Bridge at the Sumiyoshi Shrine uses the style to blur the effects of his painting.[8]

Artistic styles have been passed down for generations, producing their own masters. These styles were passed on, and their students would create other styles. Although Ogata is credited for creating Rimpa, Tawaraya developed tarashikomi (without which the Rimpa school would be quite different).

References

- ↑ Winter, John. “Japan, VI, 1: Painting materials and techniques.” Grove Oxford Art Online, 2009

- ↑ Wilson, Richard. “Tawaraya Sotatsu.” Grove Oxford Art Online, 2009

- ↑ Yuzo, Yamane. “Sotatsu.” Monumenta Nipponica Vol. 20. Sophia University, 1965

- ↑ Wilson, Richard. "Tawaraya Sotatsu". Grove Oxford Art Online, 2009

- ↑ Ogata: (1) Ogata Korin. Grove Oxford Art Online, 2009

- ↑ Winter John. “Japan, VI, 1: Painting materials and techniques.” Grove Oxford Art Online, 2009

- ↑ Peterson, Dr. “Art of China and Japan.” (information presented in classroom presentation at Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, Illinois, United States, Spring 2009)

- ↑ Ohki, Sadako. “Sakai Hoitsu [Sakai Tadanao; Ukean].” Grove Oxford Art Online, 2009