Tao Yuanming

| Tao Yuanming | |

|---|---|

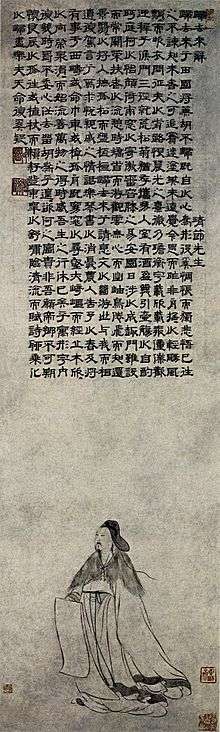

Portrait of Tao Yuanming by Chen Hongshou | |

| Born |

c. 365 Chaisang (modern Jiujiang, Jiangxi) |

| Died | 427 |

| Occupation | Official, poet |

| Notable works | Account of the Peach Blossom Spring |

| Tao Yuanming | |||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) "Tao Yuanming" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 陶淵明 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 陶渊明 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 陶潛 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (original name) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Tao Yuanming (365?–427), also known as Tao Qian or T'ao Ch'ien, was a Chinese poet who lived during the Eastern Jin (317-420) and Liu Song (420-479) dynasties. He is considered to be one of the greatest poets of the Six dynasties period. Tao Yuanming spent most of his life in reclusion, living in a small house in the countryside, reading, drinking wine, receiving the occasional guest, and writing poems in which he often reflected on the pleasures and difficulties of life in the countryside, as well as his decision to withdraw from civil service. His simple, direct, and unmannered style was at odds with the norms for literary writing in his time.[1] Although he was relatively well-known as a recluse poet in the Tang dynasty (618-907), it was not until the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), when influential literati figures such as Su Shi (1037-1101) declared him a paragon of authenticity and spontaneity in poetry, that Tao Yuanming would achieve lasting literary fame.[2] He is also regarded as the foremost representative of what would latter be known as Fields and Gardens poetry, a style of landscape poetry that found inspiration in the beauty and serenity of the natural world close at hand.

Names

In the middle of his life, Tao changed his name (keeping his family name) from Tao Yuanming (traditional Chinese: 陶淵明; simplified Chinese: 陶渊明; pinyin: Táo Yuānmíng; Wade–Giles: T'ao Yüan-ming) to Tao Qian (simplified Chinese: 陶潜; traditional Chinese: 陶潛; pinyin: Táo Qián; Wade–Giles: T'ao Ch'ien). "Master of the Five Willows", which he used when quite young, seems to be a soubriquet of his own invention.[3] There is a surviving autobiographical essay from his youth in which Tao Yuanming uses "Five Willows" to allude to himself. After this, Tao refers to himself in his earlier writings as "Yuanming"; however; it is thought that with the demise of the Eastern Jin dynasty in 420, that he began to refer to himself as "Qian", meaning "hiding", as a signification of his final withdrawal into the quiet life in the country and his decision to avoid any further participation in the political scene.[4] Tao Qian could also be translated "Recluse Tao".[5] However, this in no way implies an eremitic lifestyle or extreme asceticism; rather a comfortable dwelling, with family, friends, neighbors, musical instruments, wine, a nice library, and the beautiful scenery of a mountain farm were Tao Qian's compensation for giving up on the lifestyle of Tao Yuanming, government servant.[6]

Life

Tao Yuanming's great-grandfather was the eminent Eastern Jin general and governor, Tao Kan (259-334), and his grandfather and father also both served as government officials.[4] However, the family circumstances into which Tao Yuanming was born were only those of moderate poverty and lack of much political influence.[4]

Tao Yuanming is generally believed to have been born in the year 365 CE in Chaisang[4] (柴桑) (modern Jiujiang, Jiangxi), an area of great natural beauty. However, there is some uncertainty regarding this date, and the Chinese scholar Yuan Xingpei has argued that Tao was actually born in 352.[7] The name of his ancestral village, Chaisang, literally means "Mulberry-Bramble".[8] Nearby sights included Mount Lu, Poyang Lake (then known as P'eng-li), as well as a good selection of nature's features located in the immediate vicinity of Chaisang.[4]

Tao Yuanming ended up serving more than ten years in government service, personally involved with the sordid political scene of the times.[9] He served in both civil and military capacities, which included making several trips down the Yangzi to the capital Jiankang,[4] then a thriving metropolis, and the center of power during the Six Dynasties. The ruins of the old Jiankang walls can still be found in the modern municipal region of Nanjing. During this period, Tao Yuanming's poems begin to indicate that he was becoming torn between ambition and a desire to retreat into solitude.

Tao Yuanming had five sons.[10][11]

In the Spring of 405, Tao Yuanming was serving in the army, as aide-de-camp to the local commanding officer.[4] The death of his sister together with his disgust at the corruption and infighting of the Jin Court prompted him to resign. As he himself put it, he would not "bow like a servant in return for five bushels of grain" 為五斗米折腰, a saying which has entered common usage meaning "swallowing one's pride in exchange for a meager existence" (the 'Five bushels of grain' being the specified salary of certain low-rank officials). For the last 22 years of his life, he lived in retirement.

Tao Qian died in 427, probably at the age of 63.[12] If, however, he was in fact born in 352, he would instead have been 76 years old when he died.[7]

Works

Approximately 130 of his works survive: mostly poems or essays which depict an idyllic pastoral life of farming and drinking.

Poetry

Because his poems depict a life of farming and of drinking his home made wine, he would later be termed "Poet of the Fields". In Tao Yuanming's poems can be found superlative examples of the theme which urges its audience to drop out of official life, move to the country, and take up a cultivated life of wine, poetry, and avoiding people with whom friendship would be unsuitable, but in Tao's case this went along with actually engaging in farming. Tao's poetry also shows an inclination to fulfillment of duty, such as feeding his family. Tao's simple and plain style of expression, reflecting his back-to-basics lifestyle, first became better known as he achieved local fame as a hermit.[13] This was followed gradually by recognition in major anthologies. By the Tang Dynasty, Tao was elevated to greatness as a poet's poet, revered by Li Bai and Du Fu.

Han poetry, Jian'an poetry, the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, and the other earlier Six dynasties poetry foreshadowed some of Tao's particular symbolism and the general "returning home to the country" theme, and also somewhat separately show precursory in evolving of poetic form, based on the yuefu style which traces its origin to the Han dynasty Music Bureau. An example given of the thematic evolution of one of Tao's poetic themes is Zhang Heng's Return to the Field, written in the Classical Chinese poetry form known as the fu, or "rhapsody" style, but Tao's own poetry (including his own "Return to the Field" poem) tends to be known for its use of the more purely poetic shi which developed as a regular line length form from the literary yuefu of the Jian'an and foreshadows the verse forms favored in Tang poetry, such as gushi, or "old-style verse". Tao's poems, prose and their combination of form and theme into his own style broke new ground and became a fondly relied upon historical landmark. Much subsequent Chinese painting and literature would require no more than the mention or image of chrysanthemums by the eastern fence to call to mind Tao Yuanming's life and poetry. Later, his poetry and the particular motifs which Tao Yuanming exemplified would prove to importantly influence the innovations of Beat poetry and the 1960s poetry of the United States and Europe. Both in the 20th century and subsequently, Tao Yuanming has come to occupy a position as one of the select group of great world poets.

Poems

The following is an extract from one of his poems ("Written on the Ninth Day of the Ninth Month of the Year yi-yu"), A.D. 409:

- The myriad transformations

- unravel one another

- And human life

- how should it not be hard?

- From ancient times

- there was none but had to die,

- Remembering this

- scorches my very heart.

- What is there I can do

- to assuage this mood?

- Only enjoy myself

- drinking my unstrained wine.

- I do not know

- about a thousand years,

- Rather let me make

- this morning last forever.[14]

Another of Tao's poems is titled "I built my hut in a zone of human habitation", as translated by Arthur Waley, in A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (Alfred A. Knopf, 1919):

I BUILT my hut in a zone of human habitation,

Yet near me there sounds no noise of horse or coach.

Would you know how that is possible?

A heart that is distant creates a wilderness round it.

I pluck chrysanthemums under the eastern hedge,

Then gaze long at the distant summer hills.

The mountain air is fresh at the dusk of day:

The flying birds two by two return.

In these things there lies a deep meaning;

Yet when we would express it, words suddenly fail us.

Another, from the same source is "Returning to the Fields" (alternatively translated by others as "Return to the Field"):

WHEN I was young, I was out of tune with the herd:

My only love was for the hills and mountains.

Unwitting I fell into the Web of the World's dust

And was not free until my thirtieth year.

The migrant bird longs for the old wood:

The fish in the tank thinks of its native pool.

I had rescued from wildness a patch of the Southern Moor

And, still rustic, I returned to field and garden.

My ground covers no more than ten acres:

My thatched cottage has eight or nine rooms.

Elms and willows cluster by the eaves:

Peach trees and plum trees grow before the hall.

Hazy, hazy the distant hamlets of men.

Steady the smoke of the half-deserted village,

A dog barks somewhere in the deep lanes,

A cock crows at the top of the mulberry tree.

At gate and courtyard—no murmur of the World's dust:

In the empty rooms—leisure and deep stillness.

Long I lived checked by the bars of a cage:

Now I have turned again to Nature and Freedom.

Tao's poems greatly influenced the ensuing poetry of the Tang and Song Dynasties. A great admirer of Tao, Du Fu wrote a poem Oh, Such a Shame of life in the countryside:

- Only by wine one's heart is lit,

- only a poem calms a soul that's torn.

- You'd understand me, Tao Qian.

- I wish a little sooner I was born!

Peach Blossom Spring

Aside from his poems, Tao is also known for his short, influential, and intriguing prose depiction of a land hidden from the outside world called "Peach Blossom Spring" (桃花源記). The name Peach Blossom Spring (桃花源 Tao Hua Yuan) has since become the standard Chinese term for 'utopia'.

Critical appraisal

Zhong Rong 鍾嶸 (468-518) described Yuanming's literary style as "spare and limpid, with scarcely a surplus word."[15] In 詩品 (Poetry Gradings), Zhong Rong wrote:

[Yuanming's] sincerity is true and traditional, his verbalized inspirations supple and relaxed. When one reads his works, the fine character of the poet himself comes to mind. Ordinary men admire his unadorned directness. But such lines of his as "With happy face I pour the spring-brewed wine," and "The sun sets, no clouds are in the sky," are pure and refined in the beauty of their air. These are far from being merely the words of a farmer. He is the father of recluse poetry past and present.[15]

Su Shi (1037–1101), one of the major poets of the Song era, said that the only poet he was particularly fond of was Yuanming, who "deeply impressed [him] by what he was as a man." Su Shi exalted Yuanming's "unadorned and yet beautiful, spare and yet ample" poems, and even asserted that "neither Cao Zhi, Liu Zhen, Bao Zhao, Xie Lingyun, Li Bai, nor Du Fu achieves his stature".[16]

Huang Tingjian (1045–1105), one of the Four Masters of the Song Dynasty and a younger friend of Su Shi, said, "“When you’ve just come of age, reading these poems seems like gnawing on withered wood. But reading them after long experience in the world, it seems the decisions of your life were all made in ignorance.” [17]

Lin Yutang (1895–1976) considered Yuanming the perfect example of "the true lover of life". He praised the harmony and simplicity in Yuanming's life as well as in his style, and claimed that he "represents the most perfectly harmonious and well-rounded character in the entire Chinese literary tradition."[18]

In Great lives from history (1988), Frank Northen Magill highlights the "candid beauty" of Yuanming's poetry, stating that the "freshness of his images, his homespun but Heaven-aspiring morality, and his steadfast love of rural life shine through the deceptively humble words in which they are expressed, and as a consequence he has long been regarded one of China's most accomplished and accessible poets."[19] He also discusses what makes Yuanming unique as a poet, and why his works were perhaps overlooked by his contemporaries:

It is this fundamental love of simplicity that distinguishes T'ao Ch'ien's verses from the works of court poets of his time, who utilized obscure allusions and complicated stylistic devices to fashion verses that appealed only to the highly educated. T'ao Ch'ien, by way of contrast, seldom made any literary allusions whatsoever, and he wrote for the widest possible audience. As a consequence, he was slighted by his era's critics and only fully appreciated by later generations of readers.[20]

Gallery

Tao Yuanming has inspired not only generations of poets, but also painters and other artists.

- Tao Yuanming statue in his hometown Jiujiang

Tao Yuanming by Min Zhen, 18th century.

Tao Yuanming by Min Zhen, 18th century. From the book Wan hsiao tang-Chu chuang -Hua chuan(晩笑堂竹荘畫傳), published in 1921(民国十年).

From the book Wan hsiao tang-Chu chuang -Hua chuan(晩笑堂竹荘畫傳), published in 1921(民国十年).

Portrait of Tao Qian by Chen Hongshou (1599-1652)

Portrait of Tao Qian by Chen Hongshou (1599-1652) A Song Dynasty painting on silk portraying Tao's return to seclusion in the mountains, early 12th century. Li Peng (c. 1060-1110) inscribed a poem on this handscroll entitled Returning Home in honor of Tao Qian, otherwise known as Tao Yuanming.

A Song Dynasty painting on silk portraying Tao's return to seclusion in the mountains, early 12th century. Li Peng (c. 1060-1110) inscribed a poem on this handscroll entitled Returning Home in honor of Tao Qian, otherwise known as Tao Yuanming. A bamboo brush holder or holder of poems on scrolls, created by Zhang Xihuang in the 17th century, late Ming or early Qing Dynasty. In fanciful Chinese calligraphy in Zhang's style, the poem Returning to My Farm in the Field by the 4th century poet Tao Yuanming is incised on this cylindrical bamboo holder.

A bamboo brush holder or holder of poems on scrolls, created by Zhang Xihuang in the 17th century, late Ming or early Qing Dynasty. In fanciful Chinese calligraphy in Zhang's style, the poem Returning to My Farm in the Field by the 4th century poet Tao Yuanming is incised on this cylindrical bamboo holder.- The Three Laughers of Tiger Ravine, Soga Shohaku (1730-1781)khuy. Depicts Huiyuan (Chinese 慧遠; Hui-Yuan, Hui-Yüan in Mandarin or Fi-Yon in Gan) (334–416 AD); Tao Qian (simplified Chinese: 陶潜; traditional Chinese: 陶潛; pinyin: Táo Qián; Wade–Giles: T'ao Ch'ien) (365–427); and Lu Xiujing (chin. 陸修靜, W.-G. Liu Hsiu-ching; born 406; died 477).

Song Dynasty painting in the Litang style illustrating the theme "Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism are one". Depicts Taoist Lu Xiujing (left), official Tao Yuanming (right) and Buddhist monk Huiyuan (center, founder of Pure Land) by the Tiger stream. The stream borders a zone infested by tigers that they just crossed without fear, engrossed as they were in their discussion. Realising what they just did, they laugh together, hence the name of the picture,Three laughing men by the Tiger stream.

Song Dynasty painting in the Litang style illustrating the theme "Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism are one". Depicts Taoist Lu Xiujing (left), official Tao Yuanming (right) and Buddhist monk Huiyuan (center, founder of Pure Land) by the Tiger stream. The stream borders a zone infested by tigers that they just crossed without fear, engrossed as they were in their discussion. Realising what they just did, they laugh together, hence the name of the picture,Three laughing men by the Tiger stream. The Tale of the Peach-Blossom Land inside of the Long Corridor.

The Tale of the Peach-Blossom Land inside of the Long Corridor.- A public domain audiobook version of Peach blossom Shangri La by Tao Yuanming (in English) - 00:05:02 - 2.3MB

Translation

Editions

- Meng Erdong ed. Tao Yuanming Ji Yi Zhu ISBN 7-80626-064-1.

- Wu Zheshun ed. Tao Yuanming Ji ISBN 7-80520-683-X

- David Hinton (translator). The Selected Poems of T'ao Ch'ien (Copper Canyon Press, 1993) ISBN 1-55659-056-3.

- Karl-Heinz Pohl (translator). Der Pfirsichbluetenquell (Bochum University Press, 2002)

- Davis, A.R. T'ao Yuan-ming (Hong Kong, 1983) 2 vols.

- William Acker (translator). T'ao the Hermit: Sixty Poems by T'ao Ch'ien, 365-427 (London & New York: Thames and Hudson, 1952)

Commentary

- Ashmore, Robert. The Transport of Reading: Text and Understanding in the World of Tao Qian (365–427) (Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2010) ISBN 9780674053212

- Hightower, James R. Poetry of T'ao Ch'ien ISBN 0-19-815440-2.

- Xiaofei Tian. Tao Yuanming and Manuscript Culture: The Record of a Dusty Table ISBN 978-0-295-98553-4.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Tian, Xiaofei (2013). "From the Eastern Jin through the early Tang (317–649)" in The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–2. ISBN 1107643244.

- ↑ Tian, Xiaofei. "From the Eastern Jin through the early Tang (317–649)". pp. 221–2.

- ↑ Chang, 24-25

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chang, 22

- ↑ Hinton, 111

- ↑ Hinton, 111-112

- 1 2 Yuan & Knechtges (2014), p. 1091.

- ↑ Hinton, 110

- ↑ Davis, vii

- ↑ Chang, 25

- ↑ "Blessed I am with five sons" — Tao Yuanming, as quoted in 陶潛, 譚時霖 The complete works of Tao Yuanming (1992), p. 34

- ↑ T'ao Ch'ien on life and death: the concept of tzu-jan in his poetry by Wing-ming Chan (1981), p. 193

- ↑ Cai 2008, 122

- ↑ Translated by William Acker. Anthology of Chinese Literature, Vol. I (1965), p. 188-9

- 1 2 Zhong Rong, The Poets Graded, translated by J. Timothy Wixted, as quoted in John Minford, Joseph S. M. Lau Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations (2000)

- ↑ Su Shi, quoted by his brother Su Ziyou (1039-1112), as translated by J. Timothy Wixted; Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations (2000), p. 491

- ↑ Tao, Qian, and David Hinton. The Selected Poems of T'ao Ch'ien. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon (1993), p. 6

- ↑ Lin Yutang, in The Importance Of Living (1937), p. 116

- ↑ Frank Northen Magill, in Great lives from history: Ancient and medieval series, Vol. 5 (1988), p. 2073

- ↑ Ibid., p. 2071

References

- Cai, Zong-qi, ed. (2008). How to Read Chinese Poetry: A Guided Anthology. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13941-1

- Chang, H. C. (1977). Chinese Literature 2: Nature Poetry. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-04288-4

- Cui, Jie and Zong-qi Cai (2012). How to Read Chinese Poetry Workbook. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-15658-8

- Davis, A. R. (Albert Richard), Editor and Introduction,(1970), The Penguin Book of Chinese Verse. (Baltimore: Penguin Books).

- Hinton, David (2008). Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-10536-7 / ISBN 978-0-374-10536-5.

- Holzman, Donald. "A Dialogue with the Ancients: Tao Qian's Interrogation of Confucius" in Scott Pearce, Audrey Spiro, Patricia Ebrey (eds.), Culture and Power in the Reconstitution of the Chinese Realm, 200-600. Harward, 2001:75-98.

- Liao, Zhongan, "Tao Yuanming". Encyclopedia of China (Chinese Literature Edition), 1st ed.

- Tian, Xiaofei (2010). "From the Eastern Jin through the early Tang (317–649)". In Owen, Stephen. The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1: To 1375. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 199–285. ISBN 978-0-521-11677-0.

- Watson, Burton (1971). CHINESE LYRICISM: Shih Poetry from the Second to the Twelfth Century. (New York: Columbia University Press). ISBN 0-231-03464-4

- Yip, Wai-lim (1997). Chinese Poetry: An Anthology of Major Modes and Genres. (Durham and London: Duke University Press). ISBN 0-8223-1946-2

- Yuan, Xingpei; Knechtges, David R. (2014). "Tao Yuanming 陶淵明". In Knechtges, David R.; Chang, Taiping. Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature: A Reference Guide, Part Two. Leiden: Brill. pp. 1090–1124. ISBN 978-90-04-19240-9.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Tao Yuanming |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tao Qian. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by Qian Tao at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Tao Yuanming at Internet Archive

- Works by Tao Yuanming at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Columbia University Press web page accompanying Cai 2008 has PDF and MP3 files for four of Tao's poems (6.1-4) and CUP's web page accompanying Cui 2012 includes MP3 files of modern Chinese translations for two of these (P10-11)

- Tao Yuanming Poems in English