Tanystropheus

| Tanystropheus Temporal range: Middle Triassic, 245–228 Ma | |

|---|---|

| | |

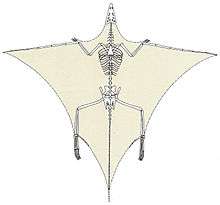

| Restored T. longobardicus skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Protorosauria |

| Family: | †Tanystropheidae |

| Genus: | †Tanystropheus |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Tanystropheus (Greek τανυς “long” + στροφαηυς “vertebra”), was a 6 metre (20 ft) long reptile that dated from the Middle Triassic period. It is recognizable by its extremely elongated neck, which measured 3 metres (10 ft) long - longer than its body and tail combined. The neck was composed of 12–13 extremely elongate vertebrae [1] Fossils have been found in Europe, the Middle East and China. Complete skeletons of juvenile individuals are most abundant in the Besano Formation of Italy, dating to 232 million years ago during the middle Triassic period (Ladinian stage).[2]

Classification

Tribelesodon, originally considered to be a pterosaur by Francesco Bassani in 1886, is now recognized as a junior synonym to Tanystropheus. The best-known species is Tanystropheus longobardicus. Other currently recognized species include T. conspicuus and T. meridensis.[3] Another junior synonym of Tanystropheus is Procerosaurus. Two specimens were initially identified as Procerosaurus: The first was described as P. cruralis by von Huene in 1902. The second was described by Antonín Jan Frič in 1878 as a species of Iguanodon (Iguanodon exogirarum, later amended to exogyrarum), and is a highly doubtful dinosaurian-like bit of bone (possibly an internal cast of a tibia) from the Cenomanian (Late Cretaceous) of the Czech Republic. He reassigned the species to Procerosaurus in 1905 intending to erect it as a new genus, unaware that the genus name was already in use. George Olshevsky in 2000 substituted Ponerosteus for this species.

In 2002, fossils of a related genus, Dinocephalosaurus, were collected in marine Triassic deposits in southwestern China. This new creature was 2.7 metres (8.9 ft) long, 1.7 metres (5.6 ft) of which was its neck and head. The specimen was described in 2004.

Anatomy

By far the most recognizable feature of Tanystropheus is its hyperelongate neck, equivalent to the combined length of the body and tail [4] The neck was composed of 12–13 hyperelongate cervical vertebrae.[1] Cervical elongation reached its peak with cervical vertebra 9, which was ten times longer than it was tall.[4] Weak development of cervical spines suggest that epaxial musculature was underdeveloped in Tanystropheus and that intrinsic back muscles (e.g., m. longus cervicis) were the driving force behind neck movement.[5] Subvertical placement of the pre and postzygapophyses suggested limited lateral movement of the neck [4] whereas cervical ribs extending off these vertebrae would have formed a ventral brace that would transmit the forces from the weight of head and neck down to the pectoral girdle, providing passive support by limiting dorsoventral flexion.[5] The body contained 13 hourglass-shaped dorsal vertebrae, two sacral vertebrae and approximately twelve caudal vertebrae with weakly developed dorsal and haemal spines along with well developed transverse processes,.[4][6]

The pectoral and pelvic girdles are notably distinct. The forelimbs are smaller and more gracile than the hindlimbs, suggesting that the center of mass for Tanystropheus was closer towards the pelvic girdle.[4] Attachment sites for the m. caudofemoralis muscle complex, coupled with soft-tissue preservation of relative muscle size, further support the proposition that Tanystropheus was a fairly bottom-heavy animal.[4]

Paleoecology

With its very long but relatively stiff neck, Tanystropheus has been often proposed and reconstructed as an aquatic or semi-aquatic reptile, a theory supported by the fact that the creature is most commonly found in semiaquatic fossil sites wherein known terrestrial reptile remains are scarce. Tanystropheus is most often considered to have been piscivorous (fish-eating), due to the presence of a long, narrow snout sporting sharp interlocking teeth. In several young specimens, three-cusped cheek teeth are present in the jaw, which might indicate an insectivorous diet; however, similar teeth patterns have been found in Eudimorphodon and Langobardisaurus, both of whom are considered piscivores. Additionally, hooklets from cephalopod tentacles and what may be fish scales have been found near the belly regions of some specimens.

In 2006, Dr. Silvio Renesto described a specimen discovered in Switzerland which preserved the impressions of skin and other soft tissue. Renesto interpreted this specimen as supporting the hypothesis that Tanystropheus lived along the shoreline, snatching fish and other marine life from the shallows with its long neck and sharp teeth. The specimen displayed an unusual "black material" around the base of the tail, containing several calcium carbonate spherules, suggesting a quite noticeable amount of muscle behind the animal's hips. In addition to containing powerful hind limb muscles, this unusually large muscle mass would have shifted the animal's weight to its rear, stabilizing the animal as it swung and maneuvered its massive neck.[4]

The skin impressions are the first reported from Tanystropheus, showing that it was covered in semi-rectangular, non-overlapping scales.[4]

Lifestyle

Tanystropheus was once thought to have lived primarily in the water due to the fact that paleontologists thought the neck would have made the animal front heavy and so needed the water to support it. However, this argument is almost entirely incorrect. In 2015, Mark Witton concluded that, although the neck made up half of the entire animal's length, it made up only 20% of the entire animal's mass. In comparison, the heads and necks of members of the group Azhdarchidae made up almost 50% of the animal's mass, yet they were clearly land based carnivores. The animal is also poorly equipped for aquatic life, with the only adaptation being a lengthened fifth toe, which suggests that it visited the water some of the time, though was not wholly dependent on it. This same research has also shown that Tanystropheus would have hunted prey like a heron.[7][8]

See also

References

- 1 2 Rieppel, O., Jiang, DY., Fraser, N.C., Hao, W.C., Motani, R., Sun, YL., Sun, ZY. 2010. Tanystropheus cf. T. longobardicus from the Early Late Triassic of Guizhou Province, Southwestern China. JVP. 30(4):1082–1089.

- ↑ Dal Sasso, C. and Brillante, G. (2005). Dinosaurs of Italy. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34514-6, ISBN 978-0-253-34514-1.

- ↑ Tanystropheus. Vertebrate Palaeontology at Milano University. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Renesto, S. (2005). "A new specimen of Tanystropheus (Reptilia Protorosauria) from the Middle Triassic of Switzerland and the ecology of the genus." Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia, 111(3): 377–394.

- 1 2 Tschanz, K. 1988. Allometry and Heterochrony in the Growth of the Neck of Triassic Prolacertiform Reptiles. Paleontology. 31:997–1011.

- ↑ Wild, R. 1973. Tanystropheus longbardicus (Bassani) (Neue Egerbnisse). in Kuhn-Schnyder, E., Peyer, B. (eds) — Triasfauna der Tessiner Kalkalpen XXIII. Schweiz. Paleont. Abh. Vol. 95 Basel, Germany.

- ↑ http://markwitton-com.blogspot.com/2015/11/the-lifestyle-of-tanystropheus-part-1.html

- ↑ http://markwitton-com.blogspot.com/2015/12/the-lifestyle-of-tanystropheus-part-2.html

Sources

- George Olshevsky expands on the history of "P." exogyrarum, on the Dinosaur Mailing List

- Huene, 1902. "Übersicht über die Reptilien der Trias" [Review of the Reptilia of the Triassic]. Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen. 6, 1-84.

- Fritsch, 1905. "Synopsis der Saurier der böhm. Kreideformation" [Synopsis of the saurians of the Bohemian Cretaceous formation]. Sitzungsberichte der königlich-böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, II Classe. 1905(8), 1-7.