Penutian languages

| Penutian | |

|---|---|

| (controversial) | |

| Geographic distribution | North America |

| Linguistic classification | Proposed language family |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | None |

|

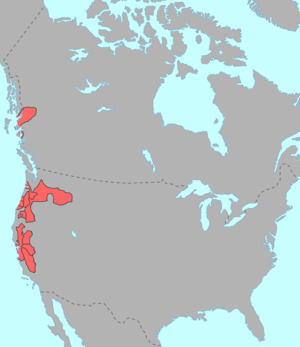

Distribution of proposed Penutian languages. | |

| |

Penutian is a proposed grouping of language families that includes many Native American languages of western North America, predominantly spoken at one time in Washington, Oregon, and California. The existence of a Penutian stock or phylum has been the subject of debate among specialists. Even the unity of some of its component families has been disputed. Some of the problems in the comparative study of languages within the phylum are the result of their early extinction and minimal documentation.[1]

Consensus was reached at a 1994 workshop on Comparative Penutian at the University of Oregon that the families within the proposed phylum's California, Oregon, Plateau, and Chinookan clusters would eventually be shown to be genetically related.[2] Subsequently, Marie-Lucie Tarpent reassessed Tsimshianic, a geographically isolated family in northern British Columbia, and concluded that its affiliation within Penutian is also probable.[3]

Some of the more recently proposed subgroupings of Penutian have been convincingly demonstrated. The Miwokan and the Costanoan languages have been grouped into an Utian language family by Catherine Callaghan.[4] Callaghan has more recently provided evidence supporting a grouping of Utian and Yokutsan into a Yok-Utian family.[5][6] There also seems to be convincing evidence for the Plateau Penutian grouping (originally named Shahapwailutan by J. N. B. Hewitt and John Wesley Powell in 1894) which would consist of Klamath–Modoc, Molala, and the Sahaptian languages (Nez Percé and Sahaptin).[7]

History of the hypothesis

Etymology and pronunciation

The name Penutian is based on the words meaning "two" in the Wintuan, Maiduan, and Yokutsan languages (which is pronounced something like [pen]) and the Utian languages (which is pronounced something like [uti]).[8]

Although perhaps originally intended to be pronounced /pɛn.ˈuːtiən/, which is indicated in some dictionaries, the term is pronounced /pəˈnuːʃən/ by most if not all linguists.

Initial concept of five core families

The original Penutian hypothesis, offered in 1913 by Roland B. Dixon and Alfred L. Kroeber, focused upon the close relationships among five California language families listed below.

That original proposal has since been called alternately Core Penutian, California Penutian, or the Penutian Kernel. In 1919 the same two authors published their linguistic evidence for the proposal.[9] The grouping, like many of Dixon & Kroeber's other phylum proposals, was based mostly on shared typological characteristics and not the standard methods used to determine genetic relationships. Starting from this early date, the Penutian hypothesis was controversial.

Prior to the 1913 Penutian proposal of Dixon and Kroeber, Albert S. Gatschet had grouped Miwokan and Costanoan into a Mutsun group (1877). That grouping, now termed Utian, was later conclusively demonstrated by Catherine Callaghan. In 1903 Dixon & Kroeber noted a "positive relationship" among Costanoan, Maidu, Wintun, and Yokuts within a "Central or Maidu Type", from which they excluded Miwokan (their Moquelumnan).[10] In 1910 Kroeber finally recognized the close relationship between the Miwokan and Costanoan languages.[11]

Sapir's expansion

In 1916 Edward Sapir expanded Dixon and Kroeber's California Penutian family with a sister stock, Oregon Penutian, which included the Coosan languages and also the isolates Siuslaw and Takelma:

- Oregon Penutian

Later Sapir and Leo Frachtenberg added the Kalapuyan and the Chinookan languages and then later the Alsean and Tsimshianic families, culminating in Sapir's 1921 four-branch classification:

- I. California Penutian grouping

- Maiduan (Maidu)

- Utian (Miwok–Costanoan)

- Wintuan (Wintu)

- Yokutsan (Yokuts)

- III. Chinookan family (Chinook)

- IV. Tsimshianic family (Tsimshian)

By the time Sapir's 1929 Encyclopædia Britannica article was published, he had added two more branches:

- Plateau Penutian family

- Klamath–Modoc (Lutuami)

- Waiilatpuan

- Sahaptian (Sahaptin)

- Mexican Penutian grouping

- Plateau Penutian family

resulting in a six-branch family:

- California Penutian

- Oregon Penutian

- Chinookan

- Tsimshianic

- Plateau Penutian

- Mexican Penutian

(Sapir's full 1929 classification scheme including the Penutian proposal can be seen here: Classification schemes for indigenous languages of the Americas#Sapir (1929): Encyclopædia Britannica.)

Further expansions

Other linguists have suggested other languages be included within the Penutian grouping:

- Macro-Penutian hypothesis (Benjamin Whorf)

Or have produced hypotheses of relationships between Penutian and other large-scale families:

- Amerind hypothesis (Joseph Greenberg)

Note: Some linguists link the Penutian hypothesis to the Zuni language. This link, earlier proposed by Stanley Newman, has now been shown to be the result of a hoax (Jane Hill 2002).[12]

Mid-twentieth century doubts

Scholars in the mid-twentieth century became concerned that similarities among the proposed Penutian language families may be the result of borrowing that occurred among neighboring peoples, not of a shared proto-language in the distant past. Mary Haas states the following regarding this borrowing:

Even where genetic relationship is clearly indicated ... the evidence of diffusion of traits from neighboring tribes, related or not, is seen on every hand. This makes the task of determining the validity of the various alleged Hokan languages and the various alleged Penutian languages all the more difficult […] [and] point[s] up once again that diffusional studies are just as important for prehistory as genetic studies and what is even more in need of emphasis, it points up the desirability of pursuing diffusional studies along with genetic studies. This is nowhere more necessary than in the case of the Hokan and Penutian languages wherever they may be found, but particularly in California where they may very well have existed side by side for many millennia.(Haas 1976:359)

Despite the concern of Haas and others, the Consensus Classification produced at a 1964 conference in Bloomington, Indiana, retained all of Sapir's groups for North America north of Mexico within the Penutian Phylum. The opposite approach was taken following a 1976 conference at Oswego, New York, when Campbell and Mithun dismissed the Penutian phylum as undemonstrated in their resulting classification of North American language families.[13]

Recent hypotheses

California Penutian and Takelma–Kalapuyan ("Takelman") are no longer accepted as valid nodes by many Penutian researchers. However, Plateau Penutian, Oregon Coast Penutian, and Yok-Utian are increasingly supported.[14] Scott DeLancey suggests the following relationships within and among language families typically assigned to the Penutian phylum:

- Maritime Penutian

- Inland Penutian

- Yok-Utian (from the Great Basin)

- Maidu (from the Great Basin or Oregon)

- Plateau Penutian

The Wintuan languages, Takelma and Kalapuya, absent from this list, continue to be considered Penutian languages by most scholars familiar with the subject, often in an Oregonian branch, though Takelma and Kalapuya are no longer considered to define a branch of Penutian.[15]

Evidence for the Penutian hypothesis

Perhaps because many Penutian languages have ablaut, vowels are difficult to reconstruct. However, consonant correspondences are common. For example, the proto-Yokuts (Inland Penutian) retroflexes */ʈ/ */ʈʼ/ correspond to Klamath (Plateau Penutian) /t͡ʃ t͡ʃʼ/, whereas the Proto-Yokuts dental */t̪/ */t̪ʰ/ */t̪ʼ/ correspond to Klamath alveolar /d t tʼ/. Kalapuya, Takelma, and Wintu do not show such obvious connections,and DeLancey has not investigated Mexican Penutian or other geographic outliers.

Below are some Penutian sound correspondences given by Lyle Campbell.[16]

- California Penutian and Klamath Sound Correspondences

| Proposed Proto-Penutian |

Klamath | Maidu | Wintu | Patwin | Yokuts | Miwok | Costanoan (Ohlone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| **p, **ph | p, ph | p | p, ph | p, ph | p, ph | p | p |

| **k | k | k | k | k | k | k | k |

| **q, **qh | q, qh | k | q | k | x (-k) | k | k |

| **m | m | m | m | m | m | m | m |

| **n | n | n | n | n | n | n | n |

| **w | w- | w- | w- | w- | w- | w- | w- |

| (l) | -l- | -l- | -l-, -l | -l-, -l | -l- | -l- | -l-. -r |

| #**r | s[C,L[V | h | tl, s | tl | ṭh | n | l, r |

| **-r- | d, l | d | (r?) | r | ṭh | (n?) | r |

| **-r | ʔ | ʔ | r | r | ṭh | n | r |

| **s | s- | s- | s- | s- |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Campbell 1997; but see Delancey & Golla 1997, Golla 2007:81–82

- ↑ Mithun 1999:308–310

- ↑ Tarpent 1996, 1997

- ↑ Callaghan 1967

- ↑ Callaghan 1997

- ↑ Callaghan 2001

- ↑ Delancey and Golla, 1997

- ↑ Dixon&Kroeber 1913a, 1913b

- ↑ Dixon&Kroeber 1919

- ↑ Dixon&Kroeber 1903

- ↑ Goddard 1996:296–297, 311

- ↑ Comment by "marie-lucie" on an article entitled "Burushaski" at languagehat.com, May 22, 2007

- ↑ Goddard 1996:317–320

- ↑ Delancey and Golla 1997

- ↑ Tarpent & Kendall 1998

- ↑ Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian languages: the historical linguistics of Native America, pg. 314. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1.

References

- Berman, Howard. (1996). The position of Molala in Plateau Penutian. International Journal of American Linguistics, 62, 1–30

- Callaghan, Catherine A. (1967). Miwok–Costanoan as a subfield of Penutian. International Journal of American Linguistics, 33, 224–227

- Callaghan, Catherine. (1997). Evidence for Yok-Utian. International Journal of American Linguistics, 63, pages 18–64

- Callaghan, Catherine. (2001). More evidence for Yok-Utian: A reanalysis of the Dixon and Kroeber sets International Journal of American Linguistics, 67 (3), pages 313–346

- Campbell, Lyle. (1997). American Indian languages: The historical linguistics of Native America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509427-1

- DeLancey, Scott; & Golla, Victor. (1997). The Penutian hypothesis: Retrospect and prospect. International Journal of American Linguistics, 63, 171–202

- Dixon, Roland R.; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1903). The native languages of California. American Anthropologist, 5, 1–26

- Dixon, Roland R.; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1913a). New linguistic families in California. American Anthropologist, 15, 647–655

- Dixon, Roland R.; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1913b). Relationship of the Indian languages of California. Science, 37, 225

- Dixon, Roland R.; & Kroeber, Alfred L. (1919). Linguistic families of California (pp. 47–118) Berkeley: University of California

- Goddard, Ives. (1996). "The Classification of the Native Languages of North America" In Languages, Ives Goddard, ed., pp. 290–324. Handbook of North American Indians Vol. 17, W. C. Sturtevant, general ed. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-048774-9

- Golla, Victor. (2007). "Linguistic Prehistory" in California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity, pp. 71–82. Terry L. Jones and Kathryn A. Klar, editors. New York: Altamira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0872-1

- Golla, Victor. (2011). California Indian Languages. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5202-6667-4

- Grant, Anthony. (1997). Coast Oregon Penutian. International Journal of American Linguistics, 63, 144–156

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1910). The Chumash and Costanoan languages. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, 9, 259–263

- Liedtke, Stefan. (1995). Wakashan, Salishan and Penutian and Wider Connections Cognate Sets. Linguistic data on diskette series, no. 09. Munich: Lincom Europa,z\v1995. ISBN 3-929075-24-5

- Liedtke, Stefan. (2007).The Relationship of Wintuan to Plateau Penutian. LINCOM studies in Native American linguistics, 55. Munich: Lincom Europa. ISBN 978-3-89586-357-8

- Mithun, Marianne. (1999). The languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23228-7 (hbk); ISBN 0-521-29875-X.

- Sapir, Edward. (1921). A bird's-eye view of American languages north of Mexico. Science, 54, 408

- Sapir, Edward. (1929). Central and North American languages. Encyclopædia Britannica (14th ed.; Vol. 5; pp. 138–141)

- Sutton, Imre, (2002) "The Ob-Ugrian/Cal-Ugrian Connection: Rediscovering 'The Discovery of California"", American Indian Culture and Research Journal,26(4): 113–120

- Tarpent, Marie-Lucie. (1996). Reattaching Tsimshianic to Penutian. Survey of California and Other Indian Languages 9:91–112

- Tarpent, Marie-Lucie. (1997). Tsimshianic and Penutian: problems, methods, results, and implications. International Journal of American Linguistics 63:65–112

- Tarpent, Marie-Lucie & Daythal Kendall. (1998). "On the relationship between Takelma and Kalapuyan: another look at 'Takelman'. Paper presented to the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas: Annual Meeting, Linguistic Society of America, New York

- Von Sadovszky, Otto J., (1996) The Discovery of California: A Cal-Ugrian Comparative Study, Istor Books 3 (Budapest: Akademiai Kiadó and Los Angeles: International Society for Trans-Oceanic Research)

External links

- Penutian (Scott DeLancey's site) (has online papers)

- Tribal Language Groups of Northern and Central California

- List of proposed Penutian languages in Oregon

- Native Tribes, Groups, Language Families and Dialects of California in 1770 (map after Kroeber)

- Mitochondrial DNA and Prehistoric Settlements: Native Migrations on the Western Edge of North America