Taj Mahal (musician)

| Taj Mahal | |

|---|---|

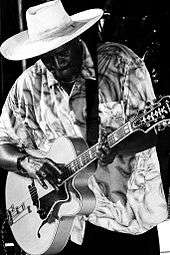

.jpg) Taj Mahal in 2005 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Henry Saint Clair Fredericks |

| Born |

May 17, 1942 Harlem, New York, United States |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1964–present |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts |

|

| Website | Tajblues.com |

| Notable instruments | |

Henry Saint Clair Fredericks (born May 17, 1942), who uses the stage name Taj Mahal, is an American blues musician. He often incorporates elements of world music into his works. A self-taught singer-songwriter and film composer who plays the guitar, piano, banjo and harmonica (among many other instruments),[2] Mahal has done much to reshape the definition and scope of blues music over the course of his almost 50-year career by fusing it with nontraditional forms, including sounds from the Caribbean, Africa and the South Pacific.[3]

Early life

Born Henry Saint Clair Fredericks, Jr. on May 17, 1942, in Harlem, New York, Mahal grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. Raised in a musical environment, his mother was a member of a local gospel choir and his father was an Afro-Caribbean jazz arranger and piano player. His family owned a shortwave radio which received music broadcasts from around the world, exposing him at an early age to world music.[4] Early in childhood he recognized the stark differences between the popular music of his day and the music that was played in his home. He also became interested in jazz, enjoying the works of musicians such as Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk and Milt Jackson.[5] His parents came of age during the Harlem Renaissance, instilling in their son a sense of pride in his Caribbean and African ancestry through their stories.[6]

Because his father was a musician, his house was frequently the host of other musicians from the Caribbean, Africa, and the U.S. His father, Henry Saint Clair Fredericks Sr., was called "The Genius" by Ella Fitzgerald before starting his family.[7] Early on, Henry Jr. developed an interest in African music, which he studied assiduously as a young man. His parents also encouraged him to pursue music, starting him out with classical piano lessons. He also studied the clarinet, trombone and harmonica.[8] When Mahal was eleven his father was killed in an accident at his own construction company, crushed by a tractor when it flipped over. This was an extremely traumatic experience for the boy.[7]

Mahal's mother later remarried. His stepfather owned a guitar which Taj began using at age 13 or 14, receiving his first lessons from a new neighbor from North Carolina of his own age who played acoustic blues guitar.[8] His name was Lynwood Perry, the nephew of the famous bluesman Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup. In high school Mahal sang in a doo-wop group.[7]

For some time Mahal thought of pursuing farming over music. He had developed a passion for farming that nearly rivaled his love of music—coming to work on a farm first at age 16. It was a dairy farm in Palmer, Massachusetts, not far from Springfield. By age nineteen he had become farm foreman, getting up a bit after 4:00 a.m. and running the place. "I milked anywhere between thirty-five and seventy cows a day. I clipped udders. I grew corn. I grew Tennessee redtop clover. Alfalfa."[9] Mahal believes in growing one's own food, saying, "You have a whole generation of kids who think everything comes out of a box and a can, and they don't know you can grow most of your food." Because of his personal support of the family farm, Mahal regularly performs at Farm Aid concerts.[9]

Taj Mahal, his stage name, came to him in dreams about Gandhi, India, and social tolerance. He started using it in 1959[10] or 1961[7]—around the same time he began attending the University of Massachusetts. Despite having attended a vocational agriculture school, becoming a member of the National FFA Organization, and majoring in animal husbandry and minoring in veterinary science and agronomy, Mahal decided to take the route of music instead of farming. In college he led a rhythm and blues band called Taj Mahal & The Elektras and, before heading for the U.S. West Coast, he was also part of a duo with Jessie Lee Kincaid.[7]

Career

In 1964 he moved to Santa Monica, California, and formed Rising Sons with fellow blues rock musician Ry Cooder and Jessie Lee Kincaid, landing a record deal with Columbia Records soon after. The group was one of the first interracial bands of the period, which likely made them commercially unviable.[11] An album was never released (though a single was) and the band soon broke up, though Legacy Records did release The Rising Sons Featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder in 1993 with material from that period. During this time Mahal was working with others, musicians like Howlin' Wolf, Buddy Guy, Lightnin' Hopkins, and Muddy Waters.[8] Mahal stayed with Columbia after the Rising Sons to begin his solo career, releasing the self-titled Taj Mahal in 1968, The Natch'l Blues in 1969, and Giant Step/De Old Folks at Home with Kiowa session musician Jesse Ed Davis from Oklahoma, who played guitar and piano (also in 1969).[1] During this time he and Cooder worked with the Rolling Stones, with whom he has performed at various times throughout his career.[12] In 1968, he performed in the film The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus. He recorded a total of twelve albums for Columbia from the late 1960s into the 1970s. His work of the 1970s was especially important, in that his releases began incorporating West Indian and Caribbean music, jazz and reggae into the mix. In 1972, he acted in and wrote the film score for the movie Sounder, which starred Cicely Tyson.[12] He reprised his role and returned as composer in the sequel, Part 2, Sounder.[13]

In 1976 Mahal left Columbia and signed with Warner Bros. Records, recording three albums for them. One of these was another film score for 1977's Brothers; the album shares the same name. After his time with Warner Bros., he struggled to find another record contract, this being the era of heavy metal and disco music.

Stalled in his career, he decided to move to Kauai, Hawaii in 1981 and soon formed the Hula Blues Band. Originally just a group of guys getting together for fishing and a good time, the band soon began performing regularly and touring.[14] He remained somewhat concealed from most eyes while working out of Hawaii throughout most of the 1980s before recording Taj in 1988 for Gramavision.[12] This started a comeback of sorts for him, recording both for Gramavision and Hannibal Records during this time.

In the 1990s he was on the Private Music label, releasing albums full of blues, pop, R&B and rock. He did collaborative works both with Eric Clapton and Etta James.[12]

In 1998, in collaboration with renowned songwriter David Forman, producer Rick Chertoff and musicians Cyndi Lauper, Willie Nile, Joan Osborne, Rob Hyman, Garth Hudson and Levon Helm of the Band, and the Chieftains, he performed on the Americana album Largo based on the music of Antonín Dvořák.

In 1997 he won Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues at the Grammy Awards, followed by another Grammy for Shoutin' in Key in 2000.[15] He performed the theme song to the children's television show Peep and the Big Wide World, which began broadcast in 2004.

In 2002, Mahal appeared on the Red Hot Organization's compilation album Red Hot and Riot in tribute to Nigerian afrobeat musician Fela Kuti. The Paul Heck produced album was widely acclaimed, and all proceeds from the record were donated to AIDS charities.

Mahal partnered up with Keb' Mo' to release a joint album TajMo on May 5, 2017.[16] The album has some guest appearances by Bonnie Raitt, Joe Walsh, Sheila E., and Lizz Wright, and has six original compositions and five covers, from artists and bands like John Mayer and The Who.[17]

Musical style

_2.jpg)

Mahal leads with his thumb and middle finger when fingerpicking, rather than with his index finger as the majority of guitar players do. "I play with a flatpick," he says, "when I do a lot of blues leads."[8] Early in his musical career Mahal studied the various styles of his favorite blues singers, including musicians like Jimmy Reed, Son House, Sleepy John Estes, Big Mama Thornton, Howlin' Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, and Sonny Terry. He describes his hanging out at clubs like Club 47 in Massachusetts and Ash Grove in Los Angeles as "basic building blocks in the development of his music."[18] Considered to be a scholar of blues music, his studies of ethnomusicology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst would come to introduce him further to the folk music of the Caribbean and West Africa. Over time he incorporated more and more African roots music into his musical palette, embracing elements of reggae, calypso,[1] jazz, zydeco, R&B, gospel music, and the country blues—each of which having "served as the foundation of his unique sound."[4] According to The Rough Guide to Rock, "It has been said that Taj Mahal was one of the first major artists, if not the very first one, to pursue the possibilities of world music. Even the blues he was playing in the early 70s – Recycling The Blues & Other Related Stuff (1972), Mo' Roots (1974) – showed an aptitude for spicing the mix with flavours that always kept him a yard or so distant from being an out-and-out blues performer."[1] Concerning his voice, author David Evans writes that Mahal has "an extraordinary voice that ranges from gruff and gritty to smooth and sultry."[2]

.jpg)

Taj Mahal believes that his 1999 album Kulanjan, which features him playing with the kora master of Mali's Griot tradition Toumani Diabate, "embodies his musical and cultural spirit arriving full circle." To him it was an experience that allowed him to reconnect with his African heritage, striking him with a sense of coming home.[5] He even changed his name to Dadi Kouyate, the first jali name, to drive this point home.[19] Speaking of the experience and demonstrating the breadth of his eclecticism, he has said:

The microphones are listening in on a conversation between a 350-year-old orphan and its long-lost birth parents. I've got so much other music to play. But the point is that after recording with these Africans, basically if I don't play guitar for the rest of my life, that's fine with me....With Kulanjan, I think that Afro-Americans have the opportunity to not only see the instruments and the musicians, but they also see more about their culture and recognize the faces, the walks, the hands, the voices, and the sounds that are not the blues. Afro-American audiences had their eyes really opened for the first time. This was exciting for them to make this connection and pay a little more attention to this music than before.[5]

Taj Mahal has said he prefers to do outdoor performances, saying: "The music was designed for people to move, and it's a bit difficult after a while to have people sitting like they're watching television. That's why I like to play outdoor festivals-because people will just dance. Theatre audiences need to ask themselves: 'What the hell is going on? We're asking these musicians to come and perform and then we sit there and draw all the energy out of the air.' That's why after a while I need a rest. It's too much of a drain. Often I don't allow that. I just play to the goddess of music-and I know she's dancing."[6]

Views on the blues

Throughout his career, Mahal has performed his brand of blues (an African American artform) for a predominantly white audience. This has been a disappointment at times for Mahal, who recognizes there is a general lack of interest in blues music among many African Americans today. He has drawn a parallel comparison between the blues and rap music in that they both were initially black forms of music that have come to be assimilated into the mainstream of society. He is quoted as saying, "Eighty-one percent of the kids listening to rap were not black kids. Once there was a tremendous amount of money involved in it ... they totally moved it over to a material side. It just went off to a terrible direction."[20] Mahal also believes that some people may think the blues are about wallowing in negativity and despair, a position he disagrees with. According to him, "You can listen to my music from front to back, and you don't ever hear me moaning and crying about how bad you done treated me. I think that style of blues and that type of tone was something that happened as a result of many white people feeling very, very guilty about what went down."[20]

Awards

Taj Mahal has received two Grammy Awards (nine nominations) over his career.[2]

- 1997 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues[15]

- 2000 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Shoutin' in Key[15]

- 2006 (Blues Music Awards) Historical Album of the Year for The Essential Taj Mahal[21]

- 2008 (Grammy Nomination) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Maestro[15]

On February 8, 2006 Taj Mahal was designated the official Blues Artist of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.[22]

In March 2006, Taj Mahal, along with his sister, the late Carole Fredericks, received the Foreign Language Advocacy Award from the Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages in recognition of their commitment to shine a spotlight on the vast potential of music to foster genuine intercultural communication.[23]

On May 22, 2011, Taj Mahal received an honorary Doctor of Humanities degree from Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina. He also made brief remarks and performed three songs. A video of the performance can be found online.[24]

In 2014, Taj Mahal received the Americana Music Association's Lifetime Achievement award.

Discography

Albums

- 1968 – Taj Mahal

- 1968 – The Natch'l Blues

- 1969 – Giant Step/De Ole Folks at Home

- 1971 – Happy Just to Be Like I Am

- 1972 – Recycling The Blues & Other Related Stuff

- 1972 – Sounder

- 1973 – Oooh So Good 'n Blues

- 1974 – Mo' Roots

- 1975 – Music Keeps Me Together

- 1976 – Satisfied 'N Tickled Too

- 1976 – Music Fuh Ya'

- 1977 – Brothers

- 1977 – Evolution

- 1987 – Taj

- 1988 – Shake Sugaree

- 1991 – Mule Bone

- 1991 – Like Never Before

- 1993 – Dancing the Blues

- 1995 – Mumtaz Mahal (with V.M. Bhatt and N. Ravikiran)

- 1996 – Phantom Blues

- 1997 – Señor Blues

- 1998 – Sacred Island aka Hula Blues (with The Hula Blues Band)

- 1999 – Kulanjan (with Toumani Diabaté)

- 2001 – Hanapepe Dream (with The Hula Blues Band)

- 2005 – Mkutano Meets the Culture Musical Club of Zanzibar

- 2008 – Maestro

- 2017 - TajMo (with Keb' Mo')

Live albums

- 1971 – The Real Thing

- 1972 – Recycling The Blues & Other Related Stuff

- 1972 – Big Sur Festival - One Hand Clapping

- 1979 – Live & Direct

- 1990 – Live at Ronnie Scott's

- 1996 – An Evening of Acoustic Music

- 2000 – Shoutin' in Key

- 2004 – Live Catch

Compilation albums

- 1980 – Going Home

- 1981 – The Best of Taj Mahal, Volume 1 – Columbia Records

- 1992 – Taj's Blues

- 1993 – World Music

- 1998 – In Progress & In Motion: 1965-1998

- 1999 – Blue Light Boogie

- 2000 – The Best of Taj Mahal

- 2000 – The Best of the Private Years

- 2001 – Sing a Happy Song: The Warner Bros. Recordings

- 2003 – Martin Scorsese Presents the Blues - Taj Mahal

- 2003 – Blues with a Feeling: The Very Best of Taj Mahal

- 2005 – The Essential Taj Mahal

- 2012 – Hidden Treasures of Taj Mahal

Various artists featuring Taj Mahal

- 1968 – The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus

- 1968 – The Rock Machine Turns You On

- 1970 – Fill Your Head With Rock

- 1985 – Conjure – Music for the Texts of Ishmael Reed

- 1990 – The Hot Spot – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack

- 1991 – Vol Pour Sidney- one title, other tracks by Charlie Watts, Elvin Jones, Pepsi, The Lonely Bears, Lee Konitz and others.

- 1992 – Rising Sons Featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder

- 1992 – Smilin' Island of Song by Cedella Marley Booker and Taj Mahal.

- 1993 – The Source by Ali Farka Touré (World Circuit WCD030 / Hannibal 1375)

- 1993 – Peace Is the World Smiling

- 1997 – Follow the Drinking Gourd

- 1997 – Shakin' a Tailfeather

- 1998 – Scrapple Soundtrack

- 1998 – Largo

- 1999 – Hippity Hop

- 2001 - "Strut" - Jimmy Smith, Dot Com Blues

- 2002 – Jools Holland's Big Band Rhythm & Blues (Rhino), contributing his version of "Outskirts of Town"[25]

- 2002 – Will The Circle Be Unbroken, Volume III lead in and first verse of title song, with Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, Alison Krauss, Doc Watson

- 2004 – Musicmakers with Taj Mahal (Music Maker 49)

- 2004 – Etta Baker with Taj Mahal (Music Maker 50)

- 2007 – Goin' Home: A Tribute to Fats Domino (Vanguard), contributing his version of "My Girl Josephine".

- 2007 – Le Coeur d'un homme (Johnny Hallyday), duet on "T'Aimer Si Mal", written by French best-selling novelist Marc Levy.

- 2009 – American Horizon with Los Cenzontles and David Hidalgo

- 2011 – Play The Blues Live From Lincoln Jazz Center with Wynton Marsalis and Eric Clapton, playing on Just a Closer Walk With Thee and Corrine, Corrina

- 2013 – Poye 2 with Bassekou Kouyate and Ngoni Ba on album "Jama Ko"

- 2013 – Winding Down with Sammy Hagar, Dave Zirbel, John Cuniberti, Mona Gnader and Vic Johnson on album "Sammy Hagar & Friends"

- 2013 – Divided & United: The Songs of the Civil War, with a version of Down by the Riverside

- 2015 – How Can a Poor Boy? with Van Morrison on Van Morrisonʻs album Duets: Re-Working the Cataglogue

Filmography

Live DVDs

- 2002 – Live at Ronnie Scott's 1988

- 2006 – Taj Mahal/Phantom Blues Band Live at St. Lucia

- 2011 – Play The Blues Live From Lincoln Jazz Center with Wynton Marsalis and Eric Clapton, playing on Just a Closer Walk With Thee and Corrine, Corrina

Movies

- 1972 – Sounder as Ike

- 1977 - Brothers

- 1991 – Bill & Ted's Bogus Journey

- 1996 – The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus

- 1998 – Outside Ozona

- 1998 – Six Days, Seven Nights

- 1998 – Blues Brothers 2000

- 1998 – Scrapple

- 2000 – Songcatcher

- 2002 – Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood

TV Shows

- 1992 – New WKRP in Cincinnati – Moss Dies as himself

- 2003 – Arthur – Big Horns George as himself

- 2004 – Theme song Peep and the Big Wide World

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Buckley, et al., 1050

- 1 2 3 Evans, et al., xii.

- ↑ Komara, 951.

- 1 2 DiCaire, 9

- 1 2 3 Tipaldi, 179–185

- 1 2 "Deep African roots help shape Taj Mahal's blues | Georgia Straight Vancouver's News & Entertainment Weekly". Straight.com. 2006-04-13. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 White, Billboard

- 1 2 3 4 Madsen, 60–73

- 1 2 George-Warren, et al., 129

- ↑ Strong, 493–494

- ↑ Weissman, 160

- 1 2 3 4 Vickers, album insert

- ↑ Eder, Richard (14 October 1976). "Film: A Sequel:'Sounder Part 2' Is Gloomy and Full of Sentimentality". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ↑ "Taj Mahal and the Hula Blues Band". Brudda.com. Archived from the original on March 8, 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-30.

- 1 2 3 4

- ↑ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "TajMo - Taj Mahal / Keb' Mo'". AllMusic. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ↑ Cunningham, Scott (March 15, 2017). "TajMo: Taj Mahal and Keb' Mo' team up for new album". Oregon Music News. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- ↑ Weissman, 117

- ↑ Elam & Jackson, 301–302

- 1 2 Tianen, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

- ↑ Archived February 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Session Laws: Chapter 19 of the Acts of 2006". Mass.gov. 2006-02-08. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- ↑ "The James W. Dodge Foreign Language Advocate Award". Northeast Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Wofford College - Commencement 2011". Wofford.edu. 2007-10-22. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

- ↑ Richie Unterberger (2002-01-08). "Jools Holland's Big Band Rhythm & Blues - Jools Holland | Songs, Reviews, Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 2015-10-07.

References

- Buckley, Peter; Buckley, Joanathan (2003). The Rough Guide to Rock (3rd ed.). London, U.K.: Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-105-4.

- Dicaire, David (2002). More Blues Singers: Biographies of 50 Artists from the Later 20th Century. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1035-3.

- Elam, Harry Justin; Jackson, Kennell (2005). Black Cultural Traffic: Crossroads in Global Performance and Popular Culture. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-09840-3.

- Evans, David (2005). The NPR Curious Listener's Guide to Blues. New York City: Berkley Publishing Group. ISBN 0-399-53072-X.

- George-Warren, Holly; Hoekstra, Dave; Natkin, Paul; Willie Nelson; et al. (2005). Farm Aid: A Song for America. Emmaus, PA: Rodale. ISBN 1-59486-285-0.

- Komara, Edward M. (2006). Encyclopedia of the Blues. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92699-8.

- Madsen, Pete (December 8, 2006). "Mojo master (interview with Taj Mahal)". Acoustic Guitar. 17 (6).

- Strong, M.C. (1998). The Great Rock Discography. Giunti. ISBN 88-09-21522-2.

- Tianen, Dave (January 12, 2003). "Taj Mahal a well-rounded blues scholar". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- Tipaldi, Art (2002). Children of the Blues: 49 Musicians Shaping a New Blues Tradition. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 0-87930-700-5.

- Vickers, Tom (2003). Blues With a Feeling/The Very Best of Taj Mahal (album insert). Private Music/BMG Heritage.

- Weissman, Dick (2005). Which Side are You On?: An Inside History of the Folk Music Revival in America. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1698-5.

- White, Timothy. "Taj mahal: a giant step ahead of his time". Billboard. 112.

- "Taj Mahal". Acoustic Magazine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taj Mahal. |

- Taj Mahal on IMDb

- Taj Mahal's official website

- Billboard review of Maestro

- Springfield, MASS raised Taj enters HOF

- Taj Mahal Interview - NAMM Oral History Library (2016)