Taforalt

|

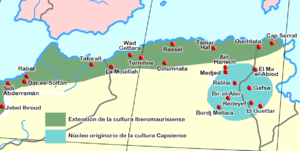

Taforalt, in the Iberomaurusian industry of NW Africa | |

location in Morocco | |

| Alternate name | Grotte des Pigeons |

|---|---|

| Location | near Taforalt village, northern Oujda region |

| Region | Morocco |

| Coordinates | 34°48′38″N 2°24′30″W / 34.81056°N 2.40833°WCoordinates: 34°48′38″N 2°24′30″W / 34.81056°N 2.40833°W |

| History | |

| Periods | Middle Paleolithic |

| Cultures | pre-Mousterian, Aterian, Iberomaurusian |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1944–1947, 1950–1955, 1969-1977 |

Taforalt (or Grotte des Pigeons) is a cave located in the northern Oujda region of Morocco near the village of Taforalt. It contains significant prehistoric archaeological remains dating back 85,000 years[1] and containing evidence associated with both the Epipaleolithic Iberomaurusian and the Middle Paleolithic Aterian industries.[2]

Site description

Grotte des Pigeons is a cave in eastern Morocco near the village of Taforalt. Human occupation and natural processes in the cave have produced a 10 m (32.8 ft) thick layer of archaeological material dating back to between 85,000 and 82,000 years ago.[1] These occupation layers include pre-Mousterian, Aterian, and Iberomaurusian industries reflecting the Middle Paleolithic and Epipaleolithic.[2] Excavations of the Iberomaurusian layers dating to approximately 12,000 years ago have recovered dozens of burials with some showing evidence of postmortem processing and potential ritual use with burials containing animal remains including horns, mandible, a hoof, and a tooth.[3][4][5] The deep and highly stratified cave floor has yielded hearths, lithics, and shell beads, among a variety of artifacts of varying ages. The dryness of the cave has contributed to the notable level of preservation found among the remains and artifacts.

Geography

The site is located around steep hills, rocky mountains, and the natural vegetation of the thermo-Mediterranean biozone including Tetraclinis articulate and Pinus halenpensis. The area itself is located in the Eastern part of Morocco near the community of Taforalt (Tafoughalt) at (34°48′38″ N, 2°24′30″ W). The large mouth of the cave opens to the northeast and has an area > 400 m2 (4,305.6 sq ft). Today the site lies around 40 km (24.9 mi) from the Mediterranean coast and at an altitude of 720 m (2,362.2 ft) above sea level.[6]

Culture

The earliest layers of human habitation in the cave, dating from 85,000-82,000 years ago, contain evidence of a pre-Mousterian industry where no evidence of Levallois lithic technology is apparent. The following (newer) layers contain side scrapers, small radial Levallois cores, and thin, bifacially worked foliate points typical of the Aterian technological industries.[6] These Aterian layers were dated to come from approximately 32,000 to >40,000 years ago,[7] though other research has found a non-Levallois industry continuing at the site until 25,000 years ago.[6] By about 21,000 years ago the Iberomaurusian industry, marked by microlithic backed bladelets, becomes the dominant archaeological material found at the site. These Iberomaurusian layers contain microlithics, ostrich egg shells, potentially ritualized primary and secondary burials, and a notable increase in land snail remains indicating a shift in dietary practices.[1][3][5][6]

Excavation History

The cave was initially discovered in 1908 and has since led to major excavations dating from 1944–1947, 1950–1955, 1969-1977, and ongoing excavations from 2003 until at least 2015. Much of the field records from the early excavations have been lost.[2] During the excavation of 1951 done by Abbé Roche, human remains were discovered that dated from the Aterian and Iberomaurusian (Epipalaeolithic) technological industries.[6] The Roche excavation encountered 10 meters of archaeological deposits with the Iberomaurusian occupying the top 2 to 3 m (6.6 to 9.8 ft). This same stratification has been encountered in the subsequent excavations in other parts of the cave. Because of the dozens of skeletons located by Roche in the 1950s and the burials located during the Bouzouggar and Barton excavations taking place since 2003, Grotte des Pigeons represents what is likely the earliest and most extensively used known prehistoric cemetery in North Africa.[5]

Stratigraphy

The stratigraphy in Grotte des Pigeons, going as deep as 10 m (32.8 ft) as in the case of Roche’s excavations, differs slightly throughout the cave but follows a simple pattern based on their color: the Grey Series overlies the Yellow Series.[2] The Grey Series dates from about 10,500 to 12,000 years ago while the Yellow Series is dated to between 12,000 years ago to the earliest occupations in the cave approximately 85,000 years ago. The Grey Series is characterized by extensive hearths and charcoal deposits, along with the burials and artifacts associated with the Iberomaurusian industry while the Yellow Series is characterized by Levallois artifacts associated with the Aterian industry. The increased density of artifacts and evidence of food production in the Grey Series is seen as a sign of year-round occupation at the site whereas the Yellow Series is seen as evidence of seasonal habitation with periods of no habitation interspersed.[6] There is a theorized 2,000 year gap of habitation between 18,000 and 20,000 years ago with this sterile layer being noted in Sector 8 of Barton’s excavations,[6] though other excavations near the mouth of the cave challenge this finding.[2]

Dating

Dating on this site has been extensive with AMS, radiocarbon, OSL, TL, and U-series methods being used in excavations going back to the 1960s.[1][2][6][8][9] Looking at all dates recovered from excavations, the habitation dates in this cave stretch from 10,500 years ago to 85,000 years ago with a shift to sedentary habitation about 12,000 years ago.[2] The local environmental data helps establish the seasonality of the site as much of the modern vegetation was utilized by the prehistoric population and follows a set seasonal process of food production. The presence of plant remains that would have been harvested in spring indicate that the cave or nearby environs were inhabited during that season. Proxies for environmental conditions during the phases of cave occupation are available from both wood charcoal and small mammal evidence. A feature of considerable interest in the charcoal record concerns the fluctuating presence of cedar in the C–F sequence. Cedrus currently grows in Morocco only from ≈1,300–2,600 m in the Rif, the Middle Atlas, and Eastern High Atlas, and its presence throughout the Taforalt record highlights a significant vegetation shift since the Holocene. In particular, the vegetation excavated by Barton in Group E is dominated by the presence of Cedrus atlantica and deciduous Quercus, with the latter declining at the expense of Cedrus. This is consistent with environmental cooling and drying that comes with a change to a montane climate. This climatic shift coincides with the dates recovered from Group E and validates the dates recovered there.[2][6][8]

Archaeological finds

Artifacts

The lithic collections recovered from the excavations at Grotte des Pigeons reflect a wide range of technologies and include unretouched and retouched flakes and bladelets, single and opposed platform bladelet cores, river cobbles, microburins, La Mouillah points, backed bladelets, Ouchtata bladelets, obtuse-ended backed bladelets, side scrapers, large bifacial tools, shell beads associated with bifacial foliates and tanged tools associated with the Aterian culture, and potential rock palettes.[1][2][5][6][10]

Faunal remains

Animal remains found at the site largely appear to be food waste though excavations in the 1950s and 2000s, 2010s have revealed burials associated with antelope horns, bovine horns, and at least one horse tooth.[3][4][5] The more sedentary Grey Series phase includes a substantial amount of land Mollusca remains in conjunction with hearths indicating extensive land snail collection and cooking.[8] The earliest layers from approximately 80,000 years ago contain shell beads of the N. gibbosulus however analysis of these shells indicate that they were collected along the Mediterranean shore after they had been dead.[1] Ash lenses from the Aterian levels around 80,000 BP contain large Otala punctate indicating small scale exploitation of land snails prior to the Grey Series.[8]

Floral remains

The vegetation species found inside the cave provide an idea what the environment was like during periods of human habitation with the charred remains of Holm oak (Quercus ilex L.) acorns, Maritime pine (Pinus pinaster Aiton) pine nuts, Juniper (Juniperus phoenicea L.), Terebinth pistachio (Pistacia terebinthus L.), and wild oat (Avena sp.) being recovered after likely being collected and processed by the previous inhabitants.[2][11]

Human remains

Sector 10, excavated by Barton and Bouzouggar, and the burial deposits excavated by Roche in the 1950s, form a contiguous and spatially demarcated collective burial area with dozens of closely spaced burials. The presence of both articulated and disarticulated bones indicates extensive use and reuse of the burial area with evidence of secondary burial and selective bone removal being practiced, often disturbing or truncating earlier burials. Some burials were covered by large stones preventing future disturbances by burials.[3][5] The Roche excavations originally estimated that they had recovered the remains of approximately 180 individuals however subsequent research at the skeletal collections have adjusted that estimate to between 35 and 40 individuals.[3] These remains were not directly dated by Roche but based on the stratigraphy they were from a greater depth, and therefore greater age, than those in Sector 10. The recent excavations taking place in Sector 10 have recovered thirteen partially articulated skeletons along with a sample of disarticulated bones. Seven bone samples from Sector 10 yielded age estimates between approximately 15,077 and 13,892 years ago, corresponding to the base of the Grey Series deposits seen in Sector 8 excavations.[5] Burials situated toward the front of the cave and those higher within the deposits are likely to be progressively younger, and hence contemporary with higher levels in the Grey Series deposits recorded in Sector 8. A range of funerary practices is apparent based on the grave excavations that have taken place. Some remains appear to have been primary inhumations while others appear to have sustained secondary inhumation after removal for potentially ritual practices.[4][5] Evidence of deliberate post-mortem modification include cut marks that are not indicative of cannibalism and extensive ochre coloring with one grave, Grave XII, containing Individual 1 with both cut marks and ochre coloring present on the majority of the nearly intact skeleton.[4] Roche’s excavations in the 1950s yielded a single mandible from the Aterian levels.[5]

A 2003 analysis[12] of masticatory and non-masticatory dental modifications among the remains recovered in the 1950s reflected a very high rate (90%)[11] of avulsion of the upper central incisors which subsequently led to increased usage of the proximal teeth. Ritual tooth removal is known elsewhere in this region at other points in prehistory and history and likely took place during the entrance to adulthood. The food processing tasks of the teeth are reflected in the heavy chipping, perhaps indicative of a gritty diet involving bone and shell. Half of the surviving teeth (51.2%) exhibited carious lesions while archaeological hunter-gatherers are expected to range between 0% – 14.3% and agriculturalists range between 2.2% - 48.1%. These numbers are likely a result of the acorns and pine nuts which would have been collected and processed, resulting in fermentable carbohydrates. The women in the population do not reflect the same proximal tooth wear as their upper central incisors were typically not removed.[12]

Occupation site utility

The inhabitants of Grotte des Pigeons were hunter-gathers equipped with the knowledge of harvesting plants and animals as the archaeological context suggests some of the burials contained evidence of baskets and grind stones which were used for food preparation.[5] Some of the foods harvested from their local environment included acorns, pine nuts, and land molluscs.[2][8][11] The site exhibits evidence that the people that lived in this area used the cave year round by the Grey Series while staying there seasonally during the Yellow Series.[2] The perforated marine shells present from the 85,000 – 82,000 year old level at Grotte des Pigeons and other sites in the nearby Maghreb dated from that period reflect an exchange network that likely existed in order to provide shells to communities 40 km from the coast (Taforalt) and further.[1] While the meaning behind the beads cannot be discerned, the presence of an apparently widespread exchange network to facilitate their transport as well as their being worked for apparent ornamentation indicate some significance behind them.[10]

World Heritage Status

This site was added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List on July 1, 1995 in the Cultural category under the name "Grotte de Taforalt".[13]

Ancient DNA

A 2000 analysis of non-metric dental traits indicated genetic continuity from the terminal Pleistocene onward in the Iberomaurusian and Capsian areas.[9] In 2013, Iberomaurusian skeletons from Taforalt and the prehistoric site of Afalou were analyzed for ancient DNA. All of the specimens belonged to maternal clades associated with either North Africa or the northern and southern Mediterranean littoral, indicating gene flow between these areas since the Epipaleolithic.[14] The ancient Taforalt individuals carried the mtDNA haplogroups U6, H, JT and V, which points to population continuity in the region dating from the Iberomaurusian period.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bouzouggar, Abdeljalil; Barton, Nick; Vanhaeren, Marian; d'Errico, Francesco; Collcutt, Simon; Higham, Tom; Hodge, Edward; Parfitt, Simon; Rhodes, Edward (2007-06-12). "82,000-year-old shell beads from North Africa and implications for the origins of modern human behavior". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (24): 9964–9969. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1891266

. PMID 17548808. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703877104.

. PMID 17548808. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703877104. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Barton, R. N. E.; Bouzouggar, A.; Collcutt, S. N.; Carrión Marco, Y.; Clark-Balzan, L.; Debenham, N. C.; Morales, J. "Reconsidering the MSA to LSA transition at Taforalt Cave (Morocco) in the light of new multi-proxy dating evidence". Quaternary International. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.085.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mariotti, Valentina; Condemi, Silvana; Belcastro, Maria Giovanna (2014-09-01). "Iberomaurusian funerary customs: new evidence from unpublished records of the 1950s excavations of the Taforalt necropolis (Morocco)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 49: 488–499. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2014.05.037.

- 1 2 3 4 Belcastro, Maria Giovanna; Condemi, Silvana; Mariotti, Valentina (2010-06-01). "Funerary practices of the Iberomaurusian population of Taforalt (Tafoughalt, Morocco, 11–12,000 BP): the case of Grave XII". Journal of Human Evolution. 58 (6): 522–532. PMID 20471665. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2010.03.011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Humphrey, Louise; Bello, Silvia M.; Turner, Elaine; Bouzouggar, Abdeljalil; Barton, Nick (2012-02-01). "Iberomaurusian funerary behaviour: Evidence from Grotte des Pigeons, Taforalt, Morocco". Journal of Human Evolution. 62 (2): 261–273. PMID 22154088. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.11.003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Barton, R. N. E.; Bouzouggar, A.; Hogue, J. T.; Lee, S.; Collcutt, S. N.; Ditchfield, P. (2013-09-01). "Origins of the Iberomaurusian in NW Africa: New AMS radiocarbon dating of the Middle and Later Stone Age deposits at Taforalt Cave, Morocco". Journal of Human Evolution. 65 (3): 266–281. PMID 23891007. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.06.003.

- ↑ Cremaschi, M., Di Lernia, S., Garcea, E. A. A. (1998). "Some Insights on the Aterian in the Libyan Sahara: Chronology, Environment, and Archaeology.". African Archaeological Review.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fernández-López de Pablo, Javier; Badal, Ernestina; García, Carlos Ferrer; Martínez-Ortí, Alberto; Serra, Alfred Sanchis. "Land Snails as a Diet Diversification Proxy during the Early Upper Palaeolithic in Europe". PLoS ONE. 9 (8): e104898. PMC 4139308

. PMID 25141047. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104898.

. PMID 25141047. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104898. - 1 2 Irish, Joel D. (2000-10-01). "The Iberomaurusian enigma: North African progenitor or dead end?". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (4): 393–410. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0430.

- 1 2 d'Errico, Francesco; Vanhaeren, Marian; Barton, Nick; Bouzouggar, Abdeljalil; Mienis, Henk; Richter, Daniel; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; McPherron, Shannon P.; Lozouet, Pierre (2009-09-22). "Additional evidence on the use of personal ornaments in the Middle Paleolithic of North Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (38): 16051–16056. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 2752514

. PMID 19717433. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903532106.

. PMID 19717433. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903532106. - 1 2 3 "Earliest evidence for caries and exploitation of starchy plant foods in Pleistocene hunter-gatherers from Morocco — Pleistocene caries and acorns — Earliest evidence for caries and exploitation of starchy plant foods in Pleistocene hunter-gatherers from Morocco — Pleistocene caries and acorns — Supporting Information". doi:10.1073/pnas.1318176111/-/dcsupplemental.

- 1 2 Bonfiglioli, B.; Mariotti, V.; Facchini, F.; Belcastro, M. G.; Condemi, S. (2004-11-01). "Masticatory and non-masticatory dental modifications in the epipalaeolithic necropolis of Taforalt (Morocco)". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 14 (6): 448–456. ISSN 1099-1212. doi:10.1002/oa.726.

- ↑ Grotte de Taforalt - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- ↑ Kefi R, Bouzaid E, Stevanovitch A, Beraud-Colomb E. "MITOCHONDRIAL DNA AND PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF PREHISTORIC NORTH AFRICAN POPULATIONS" (PDF). ISABS. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ↑ Bernard Secher, Rosa Fregel, José M Larruga, Vicente M Cabrera, Phillip Endicott, José J Pestano and Ana M González. "The history of the North African mitochondrial DNA haplogroup U6 gene flow into the African, Eurasian and American continents". BMC Evolutionary Biology. Retrieved 11 February 2016.