Alpine swift

| Alpine swift | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flying in Spain | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Apodidae |

| Genus: | Tachymarptis |

| Species: | T. melba |

| Binomial name | |

| Tachymarptis melba (Linnaeus, 1758) | |

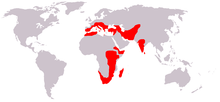

| |

| Distribution; see text for details | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Apus melba | |

The Alpine swift (Tachymarptis melba) formerly Apus melba, is a species of swift. The genus name is from the Ancient Greek takhus, "fast", and marptis, "seizer". The specific melba has no known explanation.[2]

Alpine swifts breed in mountains from southern Europe to the Himalaya. Like common swifts, they are strongly migratory, and winter much further south in southern Africa.

Swifts have very short legs which are used for clinging to vertical surfaces. They never settle voluntarily on the ground, spending most of their lives in the air living on the insects they catch in their beaks. Alpine swift are able to stay aloft in the air for up to seven months at a time, even drinking water "on the wing".

Description and biology

The bird is superficially similar to a large barn swallow or house martin. It is, however, completely unrelated to those passerine species, since swifts are in the order Apodiformes. The resemblances between the groups are due to convergent evolution, reflecting similar life styles.

Swifts have very short legs which they use only for clinging to vertical surfaces. The scientific name Apodidae comes from the Ancient Greek απους, apous, meaning "without feet". They never settle voluntarily on the ground.

Alpine swifts breed in mountains from southern Europe to the Himalaya. Like common swifts, they are strongly migratory, and winter much further south in southern Africa. They wander widely on migration, and are regularly seen in much of southern Europe and Asia. The species seems to have been much more widespread during the last ice age, with a large colony breeding, for example in the Late Pleistocene Cave No 16, Bulgaria, around 18,000–40,000 years ago.[3] The same situation has been found for Komarowa Cave near Częstochowa, Poland during a period about 20,000–40,000 years ago.[4]

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

These apodiformes build their nests in colonies in a suitable cliff hole or cave, laying two or three eggs. Swifts will return to the same sites year after year, rebuilding their nests when necessary, and pairing for life. Young swifts in the nest can drop their body temperature and become torpid if bad weather prevents their parents from catching insects nearby. They have adapted well to urban conditions, frequently nesting in old buildings in towns around the Mediterranean, where large, low-flying flocks are a familiar feature in summer.

Alpine swifts are readily distinguished from the common swifts by their larger size and their white belly and throat. They are around twice as big as most other swifts in its range, about 20 to 23 cm (7.9 to 9.1 in) in length, with a wingspan of 57 cm (22 in) and a weight of around 100 g (3.5 oz).[5] They're largely dark brown in colour, with white patches underneath the beak and on the breast that are separated by a dark brown streak. Juveniles are similar to adults, but their feathers are pale edged.[6]

In comparison, the common swift has a wingspan of around 42 cm (17 in). A dark neck band separates the white throat from the white belly. They have a short forked tail and very long swept-back wings that resemble a crescent or a boomerang but may (as in the image) be held stretched straight out. Their flight is slower and more powerful than that of their smaller relative, with a call that is a drawn-out twittering (listen at right).

Life on the wing

Alpine swifts spend most of their lives in the air, living on the insects they catch in their beaks. They drink on the wing, but roost on vertical cliffs or walls. A study published in 2013 showed Alpine swifts can spend over six months flying without having to land.[7] All vital physiological processes, including sleep, can be performed while on air.

In 2011, Felix Liechti and his colleagues at the Swiss Ornithological Institute attached electronic tags that log movement to six alpine swifts and it was discovered that the birds could stay aloft in the air for more than 200 days straight.[8]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Tachymarptis melba". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 248, 327. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ↑ Boev, Z. 1998. A range fluctuation of Alpine swift (Apus melba (L., 1758)) (Apodidae - Aves) in Northern Balkan Peninsula in the Riss-Wurm interglacial. - Biogeographia, Nuova Serie, Siena, Vol. 19, 1997: pp. 213–218.

- ↑ Tomek, Teresa & Bocheński, Zygmunt (2005): "Weichselian and Holocene bird remains from Komarowa Cave, Central Poland". Acta zoologica cracoviensia, Vol. 48A, (1-2): pp. 43–65.

- ↑ BTO Birdfacts - Alpine swift, British Trust for Ornithology, BTO.org website.

- ↑ Stevenson & Fanshawe. Field Guide to the Birds of East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Elsevier Science, 2001, ISBN 978-0856610790.

- ↑ Felix Liechti; Willem Witvliet; Roger Weber; Erich Bächler. "First evidence of a 200-day non-stop flight in a bird", Nature website, Nature Communications, article number: 2554, received 11 January 2013, published: 8 October 2013, doi:10.1038/ncomms3554 (subscription).

- ↑ Stromberg, Joseph. This Bird Can Stay in Flight for Six Months Straight: A lightweight sensor attached to alpine swifts reveals that the small migratory birds can remain aloft for more than 200 days without touching down, Smithsonian Magazine website, 8 October 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tachymarptis melba. |

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.3 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze

- Alpine swift - Species text in The Atlas of Southern African Birds

.