Székely Land

The Székely Land[1][2] or Szeklerland[3] (Hungarian: Székelyföld, pronounced [ˈseːkɛjføld]; Romanian: Ținutul Secuiesc (also Secuimea); German: Szeklerland; Latin: Terra Siculorum)[4] is a historic and ethnographic area in Romania, inhabited mainly by Hungarians and Romanians. Its cultural centre is the city of Târgu Mureș, the largest settlement in the region.[4]

The Székelys (or Szeklers), a subgroup of the Hungarian people,[5][6] live in the valleys and hills of the Eastern Carpathian Mountains, corresponding to the present-day Harghita, Covasna, and parts of Mureș counties in Romania.

Originally, the name Székely Land denoted the territories of a number of autonomous Székely seats within Transylvania. The self-governing Szekler seats had their own administrative system,[7] and existed as legal entities from medieval times until the 1870s. The privileges of the Székely and Saxon seats were abolished and seats were replaced with counties in 1876.

Along with Transylvania and eastern parts of Hungary proper, Székely Land became a part of Romania in 1920, in accordance with the Treaty of Trianon. In August 1940, as a consequence of the Second Vienna Award, the northern territories of Transylvania, including Székely Land, were ceded to Hungary, under Third Reich auspices. Northern Transylvania came under the control of Soviet and Romanian forces in 1944,[8][9][10] and were confirmed as part of Romania by the Paris peace treaties, signed after World War II, in 1947.

Under the name Magyar Autonomous Region, with Târgu-Mureș as capital,[11] parts of Székely Land enjoyed a certain level of autonomy between 8 September 1952 and 16 February 1968. There are territorial autonomy initiatives with the aim to obtain self-governance for this region within Romania.

History

The ancient period

Transylvania was populated by Thracian peoples in the First Iron Age. The area received a large influx of Scythians from the East in the first half of the first millennium BC. The Celts appeared in Transylvania in the La Tène period (c. 4th century BC).

Before the second century AD the current territory of Transylvania was the political center of the kingdom of Dacia. Dacian culture presence in southeastern Transylvania is marked by discoveries such as the flagship hoard Sâncrăieni (Harghita county) or Dacian fortresses in Covasna county (Cetatea Zânelor) or Jigodin (Harghita county).

Dacian Kingdom led by Decebal was taken after two wars, in 106 AD by the Roman Empire under the emperor Trajan, who began organizing the new Roman province of Dacia. Southeastern Transylvania was included in the provinces of Dacia Porolissensis, Dacia Apulensis and Meuse and fortified with numerous camps such as those at Inlăceni ( Praetoria Augusta) and Sânpaul (Harghita county) Breţcu (Angustia) and Oltenia (Covasna county) or Brâncoveneşti and Călugăreni (Mureș county).

After the fall of Roman Dacia, present-day territory of Szeklerland became part of the Thervingi kingdom "Gutthiuda". The migration of the Huns from the east pressured most of the German tribes to leave. In the Battle of Nedao the East Germanic Gepids defeated the Huns and founded Gepidia in the territory of present-day Transylvania.

The medieval period

The territory of Szeklerland was part of the Avar Khaganate. During this period, Avar and Slavic groups migrated into Transylvania. From around 900 to 1526 the area was under the direct control of the Hungarian state. The Szeklers presumably settled in Transylvania in the 12th century from present day Bihar and Bihor counties.

Ancient Hungarian legends suggest a connection between the Székelys and Attila's Huns. The origin of the Székely people is still debated. The Székely seats were the traditional self-governing territorial units of the Transylvanian Székelys during medieval times. (Saxons were also organised in seats.) The Seats were not part of the traditional Hungarian county system, and their inhabitants enjoyed a higher level of freedom (especially until the 18th century) than those living in the counties.

From the 12th and 13th centuries until 1876, the Székely Land enjoyed a considerable but varying amount of autonomy, first as a part of the Kingdom of Hungary, then inside the Principality of Transylvania. The autonomy was largely due to the military service the Székely provided until the beginning of the 18th century. The medieval Székely Land was an alliance of the seven autonomous Székely seats of Udvarhely, Csík, Maros, Sepsi, Kézdi, Orbai and Aranyos. The number of seats later decreased to five, when Sepsi, Kézdi and Orbai seats were united into one territorial unit called Háromszék (literally Three seats).

The main seat was Udvarhely seat, which was also called the Principal seat (Latin: Capitalis Sedes)[12] At Székelyudvarhely (Odorheiu Secuiesc) were held many national assemblies of the Székelys[13] A known exception is the 1554 assembly, which took place at Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș) [14]

Modern era

Due to the Ottoman conquest Transylvania became a semi-independent polity. From the end of the 17th century, Transylvania was part of the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary and governed by imperial governors.[15] In 1876, a general administrative reform abolished all the autonomous areas in the Kingdom of Hungary and created a unified system of counties. As a result, the autonomy of the Székely Land came to an end as well. Four counties were created in its place: Udvarhely, Háromszék, Csík, and Maros-Torda. (Only half of the territory of Maros-Torda originally belonged to Székely Land.) The isolated Aranyosszék became a district of Torda-Aranyos county.

In December 1918, in the wake of the First World War, Romanian delegates from throughout Transylvania voted to join the Kingdom of Romania. There was an attempt in Székelyudvarhely to found a "Székely Republic" on 9 January 1919; however, its creation was unsuccessful.[16] In 1920, by the Treaty of Trianon Transylvania along with further territories was ceded to the Kingdom of Romania. The Romanian language officially replaced Hungarian in the Székely Land, but Székely county boundaries were preserved, and Székely districts were able to elect their own officials at local level and to preserve Hungarian-language education.

After 1930, the Romanian authorities began to Romanianize the Hungarian population of Székely Land.[17]; the presence of minorities in political life was repressed.[18] The election of Hungarians was consistently nullified.[18] The place-names were subjected to Romanianization.[18] The minority languages were excised from official life and the local authorities were mostly led by appointed ethnic Romanians.[18]

In 1940, as a result of the Second Vienna Award Northern-Transylvania became part of Hungary again; this territory included most of the historical Székely areas. Hungarian authorities subsequently restored the pre-Trianon structure with slight modifications. Ion Gigurtu's antisemitic laws, the Romanian version of Nuremberg Laws, were replaced by Hungarian ones. The Jews of the Székely Land were subjected to particularly harsh treatment. These individuals had their citizenship status reviewed, many of them being detained. In Csíkszereda (Miercurea Ciuc), dozens of families were rounded up and expelled. The men in the area were drafted into forced labor battalions.[19] For example, 1200 Jewish males of Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș) were conscripted between 1941 and 1944; over half died in Ukraine, Poland and Hungary.[20]

However, despite discrimination and many casualties, most of the community lived in relative safety until the March 1944 occupation of Hungary by Nazi Germany. A conference devoted to the concentration of Jews in the Székely Land was held on April 28; it covered the counties of Csík, Háromszék, Maros-Torda and Udvarhely. The area's Jews were ghettoized in Szászrégen (Reghin), Sepsiszentgyörgy (Sfântu Gheorghe) and Marosvásárhely. Roundups began on May 3 and were completed within a week. The Hungarian authorities actively participated in the crimes of the Nazis. The Jews ghettoized at Sepsiszentgyörgy were later sent to Szászrégen, whence on June 4, 3149 were boarded on a train bound for the Auschwitz concentration camp. Three transports left Marosvásáhely for Auschwitz: on May 27, May 30 and June 8; altogether, they carried 7549 Jews.[19]

The Allied forces seized the area in Autumn 1944; however, the Romanian administration was expelled from these territories in October due to the activities of the Romanian paramilitary groups.[21] For instance, the Romanian Iuliu Maniu Guard terrorized the Szekler villages, butchered the local Hungarians by axe and hatchet and operated a death camp in Feldioara.[22] This paramilitary group was described as "a band of terrorist-chauvinistic criminals"[23] by the Soviets. The USSR let the Romanian authorities back to the area in March 1945.[21]

Following the territory's return to Romania after World War II, a Magyar Autonomous Region was created in 1952 under the Soviets' pressure,[24][25], which encompassed most of the land inhabited by the Székelys. In 1960, the region was renamed to Mures-Hungarian Autonomous Region. It was abolished in 1968 when the administrative reform divided Romania into the current counties. Roughly speaking, present-day Harghita County encompasses the former Udvarhely and Csík, the latter including Gyergyószék; Covasna County covers more or less the territory of the former Háromszék; and what was once Maros-Torda is mostly part of present-day Mureş County. The former Aranyosszék is today divided between Cluj and Alba counties.

Nicolae Ceaușescu got to power in 1965. For the next couple of decades, due to the Romanianization efforts, a large number of ethnic Romanians settled in Székely Land.[26] Those Székely Hungarians who possessed degrees were subjected to resettlement.[26]

In March 1990, the city of Târgu Mureș witnessed violent clashes between ethnic Romanian and Hungarian groups.

After the fall of communism, many hoped that the former Magyar Autonomous Region, abolished by Nicolae Ceauşescu's regime, would soon be restored. This did not happen; however, there are Székely autonomy initiatives[27][28] and further efforts from Székely organisations to reach a higher level of self-governance for the Székely Land within Romania.

On 2 February 2009, Romanian President Traian Băsescu met the Hungarian President László Sólyom in Budapest and discussed the issues of minority rights and regional autonomy. Băsescu stated "The Hungarian minority will never be given territorial autonomy."[29]

In 2014, the UDMR and the Hungarian Civic Party had a joint autonomy proposal for Szeklerland but the Szekler National Council also possessed its own suggestion.

In 2016, Hans G. Klemm, the United States Ambassador to Romania, together with other local officials, were pictured with a Szekler flag during his visit to Szeklerland. The photo was posted by the mayor of Sfântu Gheorghe on Facebook. The reactions of the politicians in Bucharest were turbulent. In a response Klemm affirmed that the only two flags that are important to him, as a diplomat, are the U.S. and the Romanian ones.[30][31][32]

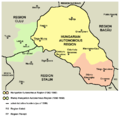

Traditional Székely Land (19th century)

Traditional Székely Land (19th century) Hungarian autonomous provinces under the Communist era

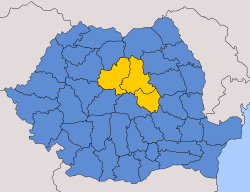

Hungarian autonomous provinces under the Communist era Present-day counties of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș within Romania

Present-day counties of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș within Romania

Constitutional issues

Article 1 of the Romanian Constitution defines the country as a "sovereign, independent, unitary and indivisible national state." It has often been argued that, as a result of this provision, any ethnic-based territorial autonomy, including that of the Székely Land, would be unconstitutional.

The Supreme Council of National Defence of Romania declared that an autonomy of the so-called Székely Land would be unconstitutional.[33]

Population

In 2002 the estimated ethnic composition of Székely Land consisted of Hungarians (61%), Romanians (33%), Germans (3%) and Roma (3%).[4] The area forms a Hungarian ethnic enclave within present-day Romania.[1][5]

The population of the Székely Land (according to the 2002 census) is 809,000, 612,043 of them Hungarians, accounting for 75.65% of the total.[34] The Hungarians represent 59% of the populations of Harghita, Covasna and Mureș counties. The percentage of Hungarians is higher in Harghita and Covasna (84.8% and 73.58% respectively), and lower in Mureș County, not all of which falls inside the traditional region (37.82%).

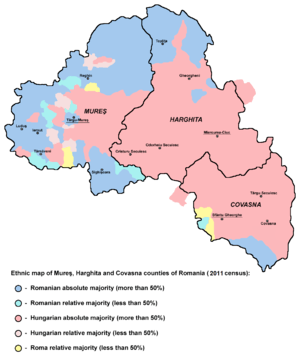

According to the 2011 official census, 609,033 Hungarians (56,8%) live in the counties of Covasna, Harghita and Mureș (out of a total population of 1,071,890 inhabitants). In Mureș county the Romanians are the most numerous (52.6%), while in the counties of Covasna and Harghita, the Hungarians make up the majority (71,6% and 82,9%).[35] The 2011 census compared to the data of the previous census (2002) also shows that the Romanian ethnic ratio in Szeklerland has been decreasing (due to emigration).[36]

Târgu Mureș is the home for the largest community of Hungarians in Romania (57,532 in 2011), but the town itself has Romanian majority (66,943 out of 127,849 inhabitants).[37]

Important centers of the Székely Land are Târgu-Mureş (Marosvásárhely), Miercurea Ciuc (Csíkszereda), Sfântu Gheorghe (Sepsiszentgyörgy), and Odorheiu Secuiesc (Székelyudvarhely).

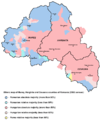

Ethnic map of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș based on the 1992 data, showing areas with Hungarian majority

Ethnic map of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș based on the 1992 data, showing areas with Hungarian majority Ethnic map of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș based on the 2002 data, showing areas with Hungarian majority

Ethnic map of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș based on the 2002 data, showing areas with Hungarian majority Ethnic map of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș based on the 2011 data, showing areas with Hungarian majority

Ethnic map of Harghita, Covasna, and Mureș based on the 2011 data, showing areas with Hungarian majority

Territory

The exact territory of present-day Szeklerland is disputed. The boundaries of the historical Székely seats and the present-day administrative divisions of Romania are dissimilar. According to Minahan its territory is an estimated 16,943 square kilometres (6,542 sq mi).[4] The autonomy proposal of the Szekler National Council consists of about 13,000 km2. This size is close to the extent of the historical Székely Land. However, it does not contain the region of Aranyos Seat. The UDMR's autonomy project covers a slightly bigger territory. It includes the whole territories of Mureș, Harghita, and Covasna counties.

Tourist attractions

- Székely fortified churches - more than 20 Székely villages count fortified churches

- Baroque church at Şumuleu Ciuc (Csíksomlyó), a major Roman Catholic pilgrimage site

- Rural tourism

- Hiking in the Carpathians

- Mofette, spas

- Mineral springs, thermal baths

- Salt mines (treatment against allergy and asthma)

- Traditional Székely handicrafts (pottery, wood carving)

- Mikó Castle

- Kálnoky Castle

- Teleki Library

- Székely National Museum (Muzeul Național Secuiesc/Székely Nemzeti Múzeum), Sfântu Gheorghe/Sepsiszentgyörgy

- Szekler Museum of Ciuc (Muzeul Secuiesc al Ciucului/Csíki Székely Múzeum), Miercurea-Ciuc/Csíkszereda

Image gallery

St. Stephen chapel of Sânzieni/Kézdiszentlélek, originally built in the 12th century

St. Stephen chapel of Sânzieni/Kézdiszentlélek, originally built in the 12th century

Pottery shop in Corund/Korond

Pottery shop in Corund/Korond Mountains surrounding the Red Lake

Mountains surrounding the Red Lake Târgu Secuiesc/Kézdivásárhely, town in the Székely Land

Târgu Secuiesc/Kézdivásárhely, town in the Székely Land A typical Székely gate in Remetea

A typical Székely gate in Remetea Decorated wooden weaving tool from Székely Land

Decorated wooden weaving tool from Székely Land Kürtőskalács, a local treat

Kürtőskalács, a local treat Salt-water lake in Sovata

Salt-water lake in Sovata Áron Gábor's sculpture in Bretcu

Áron Gábor's sculpture in Bretcu Alexander Csoma de Kőrös' statue in Covasna

Alexander Csoma de Kőrös' statue in Covasna Sacrifice cup - Csíkszentmihályi Sándor family

Sacrifice cup - Csíkszentmihályi Sándor family- Székely flag flying above House of Commons, Budapest

See also

- Hungarians in Romania

- Hungarian Autonomous Province

- Ethnic clashes of Târgu Mureş

- Szekler National Council

- Székely Himnusz

Notes

- 1 2 Béla Tomka, A Social History of Twentieth-Century Europe, Routledge, 2013, p. 411

- ↑ "Symbol of a Struggle". The New York Times. 6 February 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- ↑ George Schöpflin, Nations, Identity, Power: The New Politics of Europe, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, p. 404

- 1 2 3 4 James Minahan, Encyclopedia of the stateless nations. 4. S - Z, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002, p. 1810

- 1 2 Sherrill Stroschein, Ethnic Struggle, Coexistence, and Democratization in Eastern Europe, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p. 210 Cited: "Székely, a Hungarian sub-group that is concentrated in the mountainous Hungarian enclave"

- ↑ Ramet, Sabrina P. (1992). Protestantism and politics in eastern Europe and Russia: the communist and postcommunist eras. 3. Duke University Press. p. 160. ISBN 9780822312413.

...the Szekler community, now regarded as a subgroup of the Hungarian people.

- ↑ Józsa Hévizi, Thomas J. DeKornfeld, Autonomies in Hungary and Europe: a comparative study, Corvinus Society, 2005, p. 195

- ↑ Kurti, Laszlo (2001). The Remote Borderland. State University of New York Press. p. 33.

- ↑ Hall, Richard C. (2014). War in the Balkans. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 249.

- ↑ the Armistice Agreement with Romania

- ↑

- ↑ Voievodatul Transilvaniei. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ ""capitalis sedes" - Cutare Google". Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ http://mek.oszk.hu/03100/03187/03187.pdf

- ↑ "Transylvania". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ↑ BÉLA KÖPECZI, HISTORY OF TRANSYLVANIA, Volume III. From 1830 to 1919, Atlantic Research and Publications, Inc., 2001-2002, p. 784

- ↑ Sándor Bíró, The Nationalities Problem in Transylvania, 1867-1940: A Social History of the Romanian Minority Under Hungarian Rule, 1867-1918 and of the Hungarian Minority Under Romanian Rule, 1918-1940, Social Science Monographs, 1992, p. 486.

- 1 2 3 4 Michael Mandelbaum, The New European Diasporas: National Minorities and Conflict in Eastern Europe, Council on Foreign Relations Press, 2000, p. 33

- 1 2 "The Holocaust in Northern Transylvania", part of the Final Report of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania, at the Yad Vashem site

- ↑ Shmuel Spector, Geoffrey Wigoder (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust: Seredina-Buda-Z, p. 1289. NYU Press, 2001, ISBN 978-081-4793-76-3

- 1 2 Rogers Brubaker, Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town, Princeton University Press, 2006, p. 80

- ↑ The New Hungarian Quarterly, Volumes 31-32, Corvina Press, 1990, p. 34

- ↑ Bogdan C. Iacob, History of Communism in Europe vol. 3 / 2012, Zeta Books, 2012, p. 53

- ↑ Nicolae Edroiu, Vasile Pușcaș, The Hungarians of Romania, Fundaţia Culturalǎ Românǎ, 1996, p. 27

- ↑ Plural Societies, Volume 18, Foundation for the Study of Plural Societies., 1988, p. 71

- 1 2 Ingrid Piller, Linguistic Diversity and Social Justice: An Introduction to Applied Sociolinguistics, Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 101

- ↑ Kulish, Nicholas (2008-04-07). "Kosovo's Actions Hearten a Hungarian Enclave". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-08.

- ↑ Manifesto of the Szekely Assembly

- ↑ "World protests back Székely autonomy". Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ "Romania: US Ambassador in Minority Group Flag Controversy". abcnews. 14 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ http://www.agerpres.ro/english/2016/09/14/us-embassy-klemm-ambassador-to-all-of-romania-mae-visiting-diplomats-need-to-consider-local-sensitivities-20-32-36

- ↑ http://www.nineoclock.ro/new-reactions-in-row-over-photo-showing-american-ambassador-holding-szekely-flag-we-were-not-dishonest-with-ambassador-u-s-ambassador-says-sfantu-gheorghe-mayor/

- ↑ "Proiectul de autonomie a "Ţinutului secuiesc" - iniţiativă separatistă sau un pas pe calea unei reale autonomii locale". BBC. BBC. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ Zsolt Árus. "The szeklers and their struggle for autonomy - SZNC - Szekler National Council". Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ↑ Tab8. Populația stabilă după etnie – județe, municipii, orașe, comune. "Rezultatele recensământului din 2011" Check

|url=value (help). - ↑ Horváth István, Tonk Márton, Minority politics within the Europe of regions, Editura ISPMN, 2014, p. 205

- ↑ COMUNICAT DE PRESĂ 24 august 2012 privind rezultatele preliminare ale Recensământului Populaţiei şi al Locuinţelor – 2011 în judeţul Mureş (PDF) (Report) (in Romanian). National Institute of Statistics (Romania). 2012-08-24. p. 14. Retrieved 2015-04-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Székely Land. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Székely fortified churches in Transylvania. |